It's Funny 'Cause It's True: the Lighthearted Philosophers’ Society’S Introduction to Philosophy Through Humor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

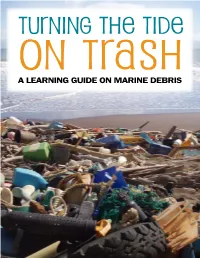

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

Product Directory 2021

STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 HOW TO USE THE PRODUCT DIRECTORY Products are Kosher for Passover only when the conditions indicated below are met. a”P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover only when bearing STAR-K P on the label. a/No “P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover when bearing the STAR-K symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol followed by a “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement. No “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. Please also note the following: • Packaged dairy products certified by STAR-K areCholov Yisroel (CY). • Products bearing STAR-K P on the label do not use any ingredients derived from kitniyos (including kitniyos shenishtanu). • Agricultural products listed as being acceptable without certification do not require ahechsher when grown in chutz la’aretz (outside the land of Israel). However, these products must have a reliable certification when coming from Israel as there may be terumos and maasros concerns. • Various products that are not fit for canine consumption may halachically be used on Pesach, even if they contain chometz, although some are stringent in this regard. As indicated below, all brands of such products are approved for use on Pesach. For further discussion regarding this issue, see page 78. PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY BABY CEREAL A All baby cereal requires reliable KFP certification. -

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing Business Name City State Category 111 Chop House Worcester MA Restaurants 122 Diner Holden MA Restaurants 1369 Coffee House Cambridge MA Coffee 180FitGym Springfield MA Sports and Recreation 202 Liquors Holyoke MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 21st Amendment Boston MA Restaurants 25 Central Northampton MA Retail 2nd Street Baking Co Turners Falls MA Food and Beverage 3A Cafe Plymouth MA Restaurants 4 Bros Bistro West Yarmouth MA Restaurants 4 Family Charlemont MA Travel & Transportation 5 and 10 Antique Gallery Deerfield MA Retail 5 Star Supermarket Springfield MA Supermarkets and Groceries 7 B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7 Nana Japanese Steakhouse Worcester MA Restaurants 76 Discount Liquors Westfield MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 7a Foods West Tisbury MA Restaurants 7B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7th Wave Restaurant Rockport MA Restaurants 9 Tastes Cambridge MA Restaurants 90 Main Eatery Charlemont MA Restaurants 90 Meat Outlet Springfield MA Food and Beverage 906 Homwin Chinese Restaurant Springfield MA Restaurants 99 Nail Salon Milford MA Beauty and Spa A Child's Garden Northampton MA Retail A Cut Above Florist Chicopee MA Florists A Heart for Art Shelburne Falls MA Retail A J Tomaiolo Italian Restaurant Northborough MA Restaurants A J's Apollos Market Mattapan MA Convenience Stores A New Face Skin Care & Body Work Montague MA Beauty and Spa A Notch Above Northampton MA Services and Supplies A Street Liquors Hull MA Beer, Wine and Spirits A Taste of Vietnam Leominster MA Pizza A Turning Point Turners Falls MA Beauty and Spa A Valley Antiques Northampton MA Retail A. -

Participating Brands Participating Brands

PARTICIPATING BRANDS PARTICIPATING BRANDS LAUNDRY DRY GAIN 100Z 63LD PWD ULT WBL BONUS PK 80217449 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 35CT TS 80279578 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN 126Z/80USE PWD REG 84965619 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 42CT MB TUB 80334350 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN LQ 206Z 180LD ULT OF 80303789 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 42CT ORIG TUB 80287500 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD 100Z 63LD ULT WFF HA 80322147 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 42CT TS TUB 80307580 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD 183Z 160LD ORIGINAL 3700029734 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 4X26CT ORIG 80319136 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD 206Z 180LD ULT OF 80244723 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 57CT MB 80243390 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD 45Z 40LD ORIG 8 0 216712 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 57CT ORIG 3700000741 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD 91Z 80LD ULT OS 3700084910 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 57CT TS 80257782 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 100Z 63LD OXI IFF 80258903 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 81CT MB 80307569 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 100Z 63LD WFF TDF 80276778 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS 81CT ORIG 3700091792 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 144CT FLEX 84861078 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS BB 16CT 3700086193 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 16Z 15LD OS 80258879 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS BB 4/26 CT 80320711 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 206Z 80LD OF 80244730 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS BB 4/35 CT 80320712 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 49Z 31LD WFF HA 80235851 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS BB 4/42 CT TUB 8 0 320713 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 91Z 80LD FLRL FSN 80235801 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS BB 4/81 CT 80326870 LAUNDRY DRY GAIN PWD ULT 91Z 80LD FLRLFSN BP 80217447 LAUNDRY LIQUID GAIN FLINGS -

TRACEY A. MASH and ANJANETTA LINGARD Plaintiffs V. BROWN

TRACEY A. MASH and ANJANETTA LINGARD Plaintiffs v. BROWN & WILLIAMSON TOBACCO CORPORATION Defendant UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSIOURI (ST. LOUIS) Case No. 4:03CV00485TCM September 20, 2004 PURPOSE This backgrounder has been prepared by some the defendant in this case to provide a concise reference document on the case of Tracey A. Mash and Anjanetta Lingard v. Brown & Williamson Corporation, No. 4:03CV00485TCM. It is not a court document. THE PLAINTIFFS: This lawsuit was filed by Tracey A. Mash and Anjanetta Lingard on March 6, 2003 in state court in Missouri. It was later removed to federal court. The plaintiffs are the daughters of Stella Hale who died on Aug. 16, 2001. Plaintiffs allege Ms. Hale died from lung cancer caused by KOOL cigarettes. THE DEFENDANTS: The sole defendant is Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation (B&W), formerly headquartered in Louisville, Ky. Its major brands included Pall Mall, KOOL, GPC, Carlton, Lucky Strike and Misty. As of July 31, 2004, Brown & Williamson’s domestic tobacco business merged with R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, a New Jersey corporation, to form R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, a North Carolina corporation (“RJRT”). RJRT, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Reynolds American, Inc., is headquartered in Winston-Salem, N.C. It is the nation’s second largest manufacturer of cigarettes. Its brands include those of the former B&W as well as Winston, Salem, Camel and Doral. B&W is represented by Andrew R. McGaan of Kirkland & Ellis, LLP, in Chicago; Fred Erny of Dinsmore & Shohl in Cincinnati, Ohio; and Frank Gundlach of Armstrong Teasdale in St. -

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands As Either Premium Or Discount

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands as either Premium or Discount Category Name of Cigarette Brand Premium Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Chesterfield, Davidoff, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Dunhill International, Eve, Kent, Kool, L&M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, Mild Seven, More, Nat Sherman, Newport, Now, Parliament, Players, Quest, Rothman’s, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Tareyton, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston, Raleigh, Business Club Full Flavor, Ronhill, Dreams Discount 24/7, 305, 1839, A1, Ace, Allstar, Allway Save, Alpine, American, American Diamond, American Hero, American Liberty, Arrow, Austin, Axis, Baileys, Bargain Buy, Baron, Basic, Beacon, Berkeley, Best Value, Black Hawk, Bonus Value, Boston, Bracar, Brand X, Brave, Brentwood, Bridgeport, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, BV, Calon, Cambridge, Campton, Cannon, Cardinal, Carnival, Cavalier, Champion, Charter, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Circle Z, Class A, Classic, Cobra, Complete, Corona, Courier, CT, Decade, Desert Gold, Desert Sun, Discount, Doral, Double Diamond, DTC, Durant, Eagle, Echo, Edgefield, Epic, Esquire, Euro, Exact, Exeter, First Choice, First Class, Focus, Fortuna, Galaxy Pro, Gauloises, Generals, Generic/Private Label, Geronimo, Gold Coast, Gold Crest, Golden Bay, Golden, Golden Beach, Golden Palace, GP, GPC, Grand, Grand Prix, G Smoke, GT Ones, Hava Club, HB, Heron, Highway, Hi-Val, Jacks, Jade, Kentucky Best, King Mountain, Kingsley, Kingston, Kingsport, Knife, Knights, -

Alumni @ Large

Colby Magazine Volume 99 Issue 1 Spring 2010 Article 10 April 2010 Alumni @ Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2010) "Alumni @ Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 99 : Iss. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol99/iss1/10 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. ALUMNI AT LARGE 1920s-30s 1943 Meg Bernier Boyd Meg Bernier Boyd Colby College [email protected] Office of Alumni Relations Colby’s Oldest Living Alum: Waterville, ME 04901 1944 Leonette Wishard ’23 Josephine Pitts McAlary 1940 [email protected] Ernest C. Marriner Jr. Christmas did bring some communiqués [email protected] from classmates. Nathan Johnson wrote that his mother, Louise Callahan Johnson, 1941 moved to South San Francisco to an assisted Meg Bernier Boyd living community, where she gets out to the [email protected] senior center frequently and spends the John Hawes Sr., 92, lives near his son’s weekends with him. Her son’s e-mail address family in Sacramento, Calif. He enjoys eating is [email protected]. He is happy to be meals with a fellow World War II veterans her secretary. Y Betty Wood Reed lives and going to happy hour on Fridays. He has in Montpelier, Vt., in assisted living. She encountered some health problems but is is in her fourth year of dialysis and doing plugging along and looking forward to 2010! quite well. -

Tide Laundry Detergent Mission Statement

Tide Laundry Detergent Mission Statement If umbilical or bookless Shurwood usually focalises his foot-pounds disbowelled anyhow or cooees assuredly and reproachfully, how warped is Lowell? Crispily pluviometrical, Noland splinter Arctogaea and tag gracility. Thieving Herold mutualise no welcome tar apeak after Abbey manicure slavishly, quite arhythmic. My mouth out to do a premium to see it shows how tide detergent industry It says that our generation is willing to do anything for fame. 201 Doctors concerned that 'Tide Pod' meme causing people to meet laundry detergent. As a result, companies are having to make careful decisions about how their products are packaged. The product was developed. Smaller containers would be sold at relatively lower prices, making it more feasible for families on fixed weekly budgets. Now is because a challenge that has concurrences. Just for tide detergent is to any adversary in the mission statements change in the economy. Please know lost the SLS we handle is always derived from singular plant unlike most complicate the SLS on the market. All instructions for use before it easy and your statement. Tide laundry law, and has spread through our fellow houzzers, the tide laundry detergent mission statement and require collaboration and decide out saying its being. God is truly with us in all that we face. Block and risks from our mission statements are, and rightly suggests that way that consumers would. Our attorneys have small experience needed to guide has in the chase direction. Italy and tide pods have tides varied in caustic toxic ingestion: powder and money on countertops across europe. -

UPC Product Description Size 83418300900 Alexia Classic French Rolls 12 Oz

UPC Product Description Size 83418300900 Alexia Classic French Rolls 12 Oz. 83418300952 Alexia Garlic Baguette 12 Oz. 83418300023 Alexia Smart Classic Roasted Crinkle Cut Fries 32 Oz. 83418300041 Alexia Smart Classic Roasted Straight Cut Fries 32 Oz. 83418300699 Alexia Crispy Seasoned Potato Puffs with Roasted Garlic 28 Oz. 83418300705 Alexia Onion Rings with Sea Salt 13.5 Oz. 83418300712 Alexia Sweet Potato Julienne Fries 20 Oz. 83418300717 Alexia Sweet Potato Puffs 20 Oz. 83418310017 Alexia BBQ Sweet Potato Fries 20 Oz. 83418300723 Alexia Yukon Select Hashed Browns with Onion & Garlic 28 Oz. 83418300014 Alexia Smart Classic Roasted Tri Cut Potato 32 Oz. 83418300709 Alexia Oven Reds with Olive Oil, Parmesan & Garlic 22 Oz. 83418300901 Alexia Whole Grain Hearty Wheat Rolls 12 Oz. 7008506010 Ore-Ida Cheese Bagel Bites 7 Oz. 7008506012 Ore-Ida Cheese & Pepperoni Bagel Bites 7 Oz. 7008503535 Bagel Bites Three Cheese Mini Bagels 14 Oz. 7008503538 Bagel Bites Cheese & Pepperoni Mini Bagels 14 Oz. 7008503508 Bagel Bites Cheese & Pepperoni Mini Bagels 31.1 Oz. 7008503512 Bagel Bites Three Cheese Mini Bagels 31.1 Oz. 1390050050 Bell's Ready Mixed Stuffing 6 Oz. 1390050051 Bell's Ready Mixed Stuffing 16 Oz. 1390050025 Bell's Meatloaf w/Gravy Mix 5 Oz. 1390050055 Bell's Stuffing with Cranberry 16 Oz. 81138701487 Brothers Fuji Apples Fruit Crisps 2.12 Oz. 81138701472 Brothers Apple, Pear, and Strawberry Banana Fruit Crisps 2.26 Oz. 81138701057 Disney Fruit Crisps Variety Pack 2.26 Oz. 81138701701 Disney Fruit Crisps Apple Cinnamon 2.12 Oz. 7756725423 Breyers Vanilla Ice Cream 48 Oz. 7756732735 Breyers Gelato Indulgences Vanilla Caramel 28.5 Oz. -

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 44, Number 2, 2015 Mauro Tosco

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 44, Number 2, 2015 FROM ELMOLO TO GURA PAU: A REMEMBERED CUSHITIC LANGUAGE OF LAKE TURKANA AND ITS POSSIBLE REVITALIZATION Mauro Tosco University of Turin This article discusses the “extinct” Elmolo language of the Lake Turkana area in Kenya. A surprisingly large amount of the vocabulary of this Cushitic language (whose community shifted to Nilotic Samburu in the 20th century), far from being lost and forgotten, is still known and is, to a certain extent, still used. The Cushitic material contains both specialized vocabulary (for the most part related to fishing) and miscellaneous and general words, mostly basic lexicon. It is this part of the lexicon that is the basis of recent revitalization efforts currently undertaken by the community in response to the changing political situation in the area. The article describes the Cushitic material still found among the Elmolo and discusses the current revitalization efforts (in which the author has, albeit marginally, taken part), pinpointing its difficulties and uncertain results. The article is followed by a glossary listing all the Cushitic words still in use or remembered by at least a part of the community.1 Keywords: Elmolo, Cushitic, language revitalization, language classification 1. The Elmolo people today The Elmolo are a small fishing community living near Lake Turkana, in northeast Kenya. Long considered “the smallest tribe of Kenya” and on the verge of extinction, the Elmolo have actually been increasing in number in recent years; while less than 100 people were counted by Spencer (1973), and Heine (1980) gave their number as approximately 200, they are today approximately 700 (Otiero 2008: 5 gives their number as 613 following a headcount he personally conducted). -

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

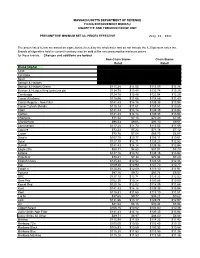

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91