The Federal Government's Implied Guarantee Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grimes County Bride Marriage Index 1846-1916

BRIDE GROOM DATE MONTH YEAR BOOK PAGE ABEL, Amelia STRATTON, S. T. 15 Jan 1867 ABSHEUR, Emeline DOUTMAN, James 21 Apr 1870 ADAMS, Catherine STUCKEY, Robert 10 Apr 1866 ADAMS, R. C. STUCKEY, Robert 24 Jan 1864 ADKINS, Andrea LEE, Edward 25 Dec 1865 ADKINS, Cathrine RAILEY, William Warren 11 Feb 1869 ADKINS, Isabella WILLIS, James 11 Dec 1868 ADKINS, M. J. FRANKLIN, F. H. 24 Jan 1864 ADLEY, J. PARNELL, W. S. 15 Dec 1865 ALBERTSON, R. J. SMITH, S. V. 21 Aug 1869 ALBERTSON, Sarah GOODWIN, Jeff 23 Feb 1870 ALDERSON, Mary A. LASHLEY, George 15 Aug 1861 ALEXANDER, Mary ABRAM, Thomas 12 Jun 1870 ALLEN, Adline MOTON, Cesar 31 Dec 1870 ALLEN, Nelly J. WASHINGTON, George 18 Mar 1867 ALLEN, Rebecca WADE, William 5 Aug 1868 ALLEN, S. E. DELL, P. W. 21 Oct 1863 ALLEN, Sylvin KELLUM, Isaah 29 Dec 1870 ALSBROOK, Leah CARLEY, William 25 Nov 1866 ALSTON, An ANDERS, Joseph 9 Nov 1866 ANDERS, Mary BRIDGES, Taylor 26 Nov 1868 ANDERSON, Jemima LE ROY, Sam 28 Nov 1867 ANDERSON, Phillis LAWSON, Moses 11 May 1867 ANDREWS, Amanda ANDREWS, Sime 10 Mar 1871 ARIOLA, Viney TREADWELL, John J. 21 Feb 1867 ARMOUR, Mary Ann DAVIS, Alexander 5 Aug 1852 ARNOLD, Ann JOHNSON, Edgar 15 Apr 1869 ARNOLD, Mary E. (Mrs.) LUXTON, James M. 7 Oct 1868 ARRINGTON, Elizabeth JOHNSON, Elbert 31 Jul 1866 ARRINGTON, Martha ROACH, W. R. 5 Jan 1870 ARRIOLA, Mary STONE, William 9 Aug 1849 ASHFORD, J. J. E. DALLINS, R. P. 10 Nov 1858 ASHFORD, L. A. MITCHELL, J. M. 5 Jun 1865 ASHFORD, Lydia MORRISON, Horace 20 Jan 1866 ASHFORD, Millie WRIGHT, Randal 23 Jul 1870 ASHFORD, Susan GRISHAM, Thomas C. -

Anacortes Museum Research Files

Last Revision: 10/02/2019 1 Anacortes Museum Research Files Key to Research Categories Category . Codes* Agriculture Ag Animals (See Fn Fauna) Arts, Crafts, Music (Monuments, Murals, Paintings, ACM Needlework, etc.) Artifacts/Archeology (Historic Things) Ar Boats (See Transportation - Boats TB) Boat Building (See Business/Industry-Boat Building BIB) Buildings: Historic (Businesses, Institutions, Properties, etc.) BH Buildings: Historic Homes BHH Buildings: Post 1950 (Recommend adding to BHH) BPH Buildings: 1950-Present BP Buildings: Structures (Bridges, Highways, etc.) BS Buildings, Structures: Skagit Valley BSV Businesses Industry (Fidalgo and Guemes Island Area) Anacortes area, general BI Boat building/repair BIB Canneries/codfish curing, seafood processors BIC Fishing industry, fishing BIF Logging industry BIL Mills BIM Businesses Industry (Skagit Valley) BIS Calendars Cl Census/Population/Demographics Cn Communication Cm Documents (Records, notes, files, forms, papers, lists) Dc Education Ed Engines En Entertainment (See: Ev Events, SR Sports, Recreation) Environment Env Events Ev Exhibits (Events, Displays: Anacortes Museum) Ex Fauna Fn Amphibians FnA Birds FnB Crustaceans FnC Echinoderms FnE Fish (Scaled) FnF Insects, Arachnids, Worms FnI Mammals FnM Mollusks FnMlk Various FnV Flora Fl INTERIM VERSION - PENDING COMPLETION OF PN, PS, AND PFG SUBJECT FILE REVIEW Last Revision: 10/02/2019 2 Category . Codes* Genealogy Gn Geology/Paleontology Glg Government/Public services Gv Health Hl Home Making Hm Legal (Decisions/Laws/Lawsuits) Lgl -

Fannie Mae Proposed Underserved Markets Plan

Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan For the Manufactured Housing, Affordable Housing Preservation, and Rural Housing Markets May 8, 2017 5.8.2017 1 of 239 Fannie Mae’s Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan must receive a non-objection from FHFA before becoming effective. The Objectives in the proposed and final Plan may be subject to change based on factors including public input, FHFA comments, compliance with Fannie Mae’s Charter Act, safety and soundness considerations, and market or economic conditions. Disclaimer Fannie Mae’s Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan must receive a non-objection from FHFA before becoming effective. The Objectives in the proposed and final Plan may be subject to change based on factors including public input, FHFA comments, compliance with Fannie Mae’s Charter Act, safety and soundness considerations, and market or economic conditions. 5.8.2017 2 of 239 Fannie Mae’s Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan must receive a non-objection from FHFA before becoming effective. The Objectives in the proposed and final Plan may be subject to change based on factors including public input, FHFA comments, compliance with Fannie Mae’s Charter Act, safety and soundness considerations, and market or economic conditions. Table of Contents I. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................... 10 II. Introduction to the Duty to Serve Plans ........................................................................................................................ -

Guaranteed to Fail: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Debacle

GUARANTEED TO FAIL Fannie Mae, Freddie MAc and the Debacle of Mortgage Finance V i r a l a c h a r ya M at t h e w r i c h a r d s o n s t i j n V a n n ieuwerburgh l a w r e n c e j . w h i t e Guaranteed to Fail Fannie, Freddie, and the Debacle of Mortgage Finance Forthcoming January 2011, Princeton University Press Authors: Viral V. Acharya, Professor of Finance, NYU Stern School of Business, NBER and CEPR Matthew Richardson, Charles E. Simon Professor of Applied Financial Economics, NYU Stern School of Business and NBER Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, Associate Professor Finance, NYU Stern School of Business, NBER and CEPR Lawrence J. White, Arthur E. Imperatore Professor of Economics, NYU Stern School of Business To our families and parents - Viral V Acharya, Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, Matt Richardson, and Lawrence J. White 1 Acknowledgments Many insights presented in this book were developed during the development of two earlier books that the four of us contributed to at NYU-Stern: Restoring Financial Stability: How to Repair a Failed System (Wiley, March 2009); and Regulating Wall Street: The Dodd-Frank Act and the New Architecture of Global Finance (Wiley, October 2010). We owe much to all of our colleagues who contributed to those books, especially those who contributed to the chapters on the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs): Dwight Jaffee (who was visiting Stern during 2008-09), T. Sabri Oncu (also visiting Stern during 2008-10), and Bob Wright. -

Arguing Their World: the Representation of Major Social and Cultural Issues in Edna Ferber’S and Fannie Hurst’S Fiction, 1910-1935

1 ARGUING THEIR WORLD: THE REPRESENTATION OF MAJOR SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ISSUES IN EDNA FERBER’S AND FANNIE HURST’S FICTION, 1910-1935 A dissertation presented By Kathryn Ruth Bloom to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2018 2 ARGUING THEIR WORLD: THE REPRESENTATION OF MAJOR SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ISSUES IN EDNA FERBER’S AND FANNIE HURST’S FICTION, 1910-1935 A dissertation presented By Kathryn Ruth Bloom ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2018 3 ABSTRACT BetWeen the early decades of the twentieth-century and mid-century, Edna Ferber and Fannie Hurst were popular and prolific authors of fiction about American society and culture. Almost a century ago, they were writing about race, immigration, economic disparity, drug addiction, and other issues our society is dealing with today with a reneWed sense of urgency. In spite of their extraordinary popularity, by the time they died within a feW months of each other in 1968, their reputations had fallen into eclipse. This dissertation focuses on Ferber’s and Hurst’s fiction published betWeen approximately 1910 and 1935, the years in Which both authors enjoyed the highest critical and popular esteem. Perhaps because these realistic narratives generally do not engage in the stylistic experimentation of the literary world around them, literary scholars came to undervalue their Work. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

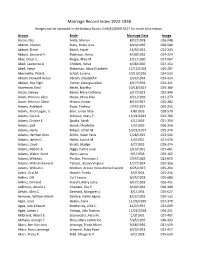

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A. -

Pilot Schooner ALABAMA (ALABAMIAN) HAER No

Pilot Schooner ALABAMA (ALABAMIAN) HAER No. MA-64 Vineyard Haven Martha's Vineyard Dukes County Li A ^ ^ Massachusetts ' l PHOTOGRAPHS REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, DC 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Pilot Schooner ALABAMA (ALABAMIAN) HAER No. MA-64 Rig/Type of Craft: 2-masted schooner; mechanically propelled, sail assisted Trade: pilot vessel Official No.: 226177 Principle Dimensions: Length (overall): 88.63' Gross tonnage: 70 Beam: 21.6* Net tonnage: 35 Depth: 9.7' Location: moored in harbor at Vineyard Haven Martha's Vineyard Dukes County Massachusetts Date of Construction: 1925 Designer: Thomas F. McManus Builder: Pensacola Shipbuilding Co., Pensacola, Florida Present Owner: Robert S. Douglas Box 429 Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts 02568 Present Use: historic vessel Significance: ALABAMA was designed by Thomas F. McManus, a noted fi: schooner and yacht designer from Boston, Massachusetts. She was built during the final throes of the age of commercial sailing vessels in the United States and is one of a handful of McManus vessels known to survive. Historian: W. M. P. Dunne, HAER, 1988. Schooner Alabama HAER No. MA-64 (Page 2) TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue 3 The Colonial Period at Mobile 1702-1813 5 Antebellum Mobile Bar Pilotage 10 The Civil War 17 The Post-Civil War Era 20 The Twentieth Century 25 The Mobile Pilot Boat Alabama, Ex-Alabamian, 1925-1988 35 Bibliography 39 Appendix, Vessel Documentation History - Mobile Pilot Boats 18434966 45 Schooner Alabama HAER No. MA-64 (Page 3) PROLOGUE A map of the Americas, drawn by Martin Waldenseemuller in 1507 at the college of St. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Fannie Rosalind Hicks Givens (1876-1947), Artist, Policewoman and Political Activist

H-Kentucky Fannie Rosalind Hicks Givens (1876-1947), artist, policewoman and political activist Discussion published by KyWoman Suffrage on Friday, May 21, 2021 This biosketch was written by Dr. Carol Mattingly, Professor Emerita of English at the University of Louisville. For her full project on “African American Women and Suffrage in Louisville,” visit https://arcg.is/1O8muW. Fannie Rosalind Hicks was born in or near Chicago but moved to Louisville at a young age; her parents were born in Kentucky and probably had been enslaved, as they are frequently referenced as having “migrated north” after the Civil War. Her death certificate lists her parents as unknown. She was probably born in 1876, but documents provide various birth dates. Her death certificate and passports give her birth as 1876, but her gravestone lists 1864. Fannie Hicks attended and taught at State University (later Simmons). In 1895, she married James Edward Givens, a graduate of Harvard and professor at State University; the couple had one adopted daughter, also named Fannie, who taught in the Louisville Public Schools. A nephew, James Givens, came to live with the Givens family at a relatively young age. He became a successful Louisville caterer and leader in the community. James, Fannie’s husband, died in 1910; Fannie remained a widow until her death in 1947. The photo below was taken c1909 while she was a member of the Women's Auxiliary to the Local Business Men's League of Louisville. givens1909.jpg Citation: KyWoman Suffrage. Fannie Rosalind Hicks Givens (1876-1947), artist, policewoman and political activist. H-Kentucky. -

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS RICHARDSON, FANNIE BELLE TAYLOR: Papers, 1900-1960 Pre-Acc. Compiled By: RWD Revise

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS RICHARDSON, FANNIE BELLE TAYLOR: Papers, 1900-1960 Pre-Acc. Compiled by: RWD Revised by DH 10 cubic feet 1941-1960* *Photo and other copies of documents date back to 1741 CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 A - Cross Reference Index to this entire file of Eisenhower Correspondence and related papers. AA - Correspondence (and pertinent papers and notes) which reached me after May 31, 1960 (1) (2) Africa: Wilbur W. Yoakum, Tripoli, Libya, North Africa Album Collection: Regarding my collection of pictures and Album material Alexander, 1554, Festus Rufus, Stony Point, NC Alexander, Mrs. Pearl Dearing, Norman, Oklahoma Almanac, 1958 edition, RSII-88 and RSII-89 Amos, Mrs. Faye D., New Brighton, PA Anderson, 1973 William Adlai, Chicago, IL and Bayamon, Puerto Rico Apostolides, Mrs. Emanuel (Alexandra) [San Francisco, California] Arkwright, Mrs. Blaine, Angola, Indiana, (1050 Geneva Eisenhour) Arlowe, Mrs. Herbert H. Seattle, Wash. (Georgia Martha Rowe RSII-39A) (Desc. of 1337 Nelson Elcany Sigman) Armstrong, Mrs. Lola Lamar, MO (1851 Lola E. Isenhower) Arndt, Mrs. Garland A. Claremont, NC (1551 Huldah Elizabeth Sigmon) AUSTRIA: Frank, Karl Friederich von... Bailey, Mrs. Lulu Zionsville, Indiana (Lulu Isenhour M84) (Dau. of 1377 John E. Isenhour) Baker, Mrs. Mary I. Jacksonville, Florida (Mary Kyle Icenhour p131) (Dau. of 292 Jesse Allen Icenhour) Baker, Mrs. Minnie Jackson, Mich. (204 Minnie Isenhower) Barg, Mrs. Carl L. Hamilton, Kansas (Blanche Marion Winler 141) Desc. Of 1329 Ellana M. Icenhower) Barger, Mrs. Glenn L. North Carolina (247 Mary Ethel Fisher) 2 Barno Collection, M. (Michael F.) RSII-89 in Oklahoma Military Academy (Library) Claremore, Oklahoma.. -

Cemetery-Burials by Last Name

Cemetery - Burials By Last Name Last Name First Name Middle Maiden Name Section Block Lot Grave Died Age Burial Date AARONS PATRICIA LYNN B 214 D 8/20/2010 AASEN CARL MASONIC 119 2 2 3/2/1983 83 AASEN FLORENCE LUCILLE MASONIC 119 4 2/21/1990 66 2/24/1990 AASEN JUDITH MASONIC 119 3 3 3/7/1977 78 ABBE IVAN ROBERT J 2 8 A 7/2/1953 24 ABBOTT CHARLES A 78A 5 6/4/1912 28 ABBOTT GARY DELBERT NATURES PATHWAY E 19 1/7/2015 70 1/23/2015 ABBOTT KETURAH OLD CEMETERY 368 4/23/1907 0 ABEL MAGDALINE OLD CEMETERY 97 2/13/1905 0 ABERNATHY CLYDE C. A 74A 5 1/16/1957 77 ABERNATHY EDGAR W. I 6 8 D 8/14/1976 68 ABERNATHY IMA I 6 8 E 7/25/1980 72 ACHILLES ALBERT O. D 14 8 A 12/21/1963 0 ACHILLES FRED A 93 4 9/2/1920 71 ACHILLES MARY D 14 8 B 5/22/1965 74 ACHILLES OLGA A 93 5 7/5/1937 84 ACHORN OLIVER OLD CEMETERY 397 2/28/1894 0 ACKER JOHN A 7 4 8/12/1917 34 ACKER JOHN OLD CEMETERY 72 1/26/1901 0 ACKERMAN BERNICE LOIS J 2 8 B 11/12/1988 86 11/16/1988 ADAMS BRANDON J. J 12 1 N 9/14/1974 0 Friday, March 23, 2018 Page 1 of 690 Last Name First Name Middle Maiden Name Section Block Lot Grave Died Age Burial Date ADAMS ELIAS E 1 4 A 11/27/1923 73 ADAMS HARRIET B 227 C 10/22/1958 81 ADAMS INA CHASE B 100 D 8/22/1950 72 ADAMS LLEWELLYN B 100 C 9/14/1936 63 ADAMS MIRIAM REEL L 3 15 A 11/4/2014 95 11/13/2014 ADAMS NELLIE OR MILLIE 1ST ADDITION 182 5 9/13/1913 0 ADAMS PAMELA J.