The Boston Foundation and the Cleanup of Boston Harbor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Comment, October 12, 1972

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1972 The ommeC nt, October 12, 1972 Bridgewater State College Volume 52 Number 6 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1972). The Comment, October 12, 1972. 52(6). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/296 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. , pt ~; Ii ; I _ J i; j i .. _ i The COMMENT 2' P Vol. No. BRIDGEWATER STATE COLLEGE October l 1972 7 Henry Werner To Resign Fro Tn Post Bridgewater-Henry F. Werner, for the past 12 years asssitant to the president at Bridgewater State College, will retire on Oct. 20. Before • his tenure at Bridgewater, Werner, graduate of Fitchburg State College and Rutgers University, had heen for 21 years headmaster of the Summit Boys School in Cincinnati, Ohio. For 15 years previous to the Cincinnati position, he was head of the junior school at the Newman Prep Schoolin Lakewood, N.J., the oldest lay-conducted Catholic prep school in the country. On the faculty during those years were Dr. Clement Maxwell. past pl'esident of Bridgewater State College and Christopher. Weldon cUlTently bishop of the Springfield Diocese. Among the many students from . across the country .he taught a number of boys from prominent families. While at Newman, he taught George M. Cohan, Jr., son of the actor-playwright; Harry Sinclair, Jr., son of the oil tycoon; David Elkins, III, grandson of the founder of the college that bears his name; Dan Reeves, owner of the Los Angelos Rams,and William K. -

Sitting with a Standell Tony Valentino Stops by the Flying Eye Radio

For Immediate Release Contact: Andy Goldfinger Grand Poohbah Flying Eye Radio Network ASCAP/BMI (818) 917-5183 Sitting With A Standell Tony Valentino Stops By The Flying Eye Radio Network "The Music Business Is A Cruel And Shallow Money Trench, A Long Plastic Hallway Where Thieves And Pimps Run Free, And Good Men Die Like Dogs. There's Also A Negative Side." Hunter S. Thompson, Writer, Philosopher Malibu, California, November 01, 2012 - This week’s addition of the Flying Eye Radio Network’s Music Gumbo is sure to entertain as host Andy Goldfinger sits down with music legend Tony Valentino. Known as one of the “Godfather’s of Punk,” Valentino is best recognized for being the founding guitarist of the popular 60s band, The Standells. Formed in Los Angeles during the early 1960s, the garage rock band hit big with their song “Dirty Water” in 1966. Valentino created the famous guitar rift for the classic song that has been listed in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's "500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.” The song has also become an anthem to Boston athletics and can be heard after every Boston Red Sox home victory and during Boston Celtics and Boston Bruins home games. Valentino and The Standells can even be seen in an episode of the popular 60s sitcom, The Munsters, playing a cover of the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Join in for Music Gumbo's interview with Tony Valentino airing on November 1 to hear more about this “Godfather of Punk” that has toured with such bands as The Rolling Stones, Sonny & Cher, Paul Revere & the Raiders, and Otis Redding. -

Playboy Manbaby Jim Louvau

Playboy Manbaby Jim Louvau Apr 24, 2018 17:48 BST PLAYBOY MANBABY: Phoenix Spazz- Punks Release New Album "Lobotomobile" - Announce US Tour Dates | Dirty Water Records USA PROMO ACCESS View embedded content here Playboy Manbabyhave been playing, touring, and dropping records for more than five years. Riding the momentum wave of 2017's epic "Don't Let It Be" album, (which was originally released on cassette from Lolipop Records, and is now available on limited colored vinyl through Dirty Water Records USA)the band have now unleashed Lobotomobile on the public. The 11-song full-length is available digitally and in limited-edition quantities on vinyl, cassette, and CD. View embedded content here Watch video on YouTube here The band features Robbie Pfeffer on vocals, TJ Friga on guitar, Chris Hudson on bass, Chad Dennis on drums, Austin Rickert on sax, and Dave Cosme on trumpet and percussion. Together, the band creates jumpy, raucous music — topped with sharp, thought-provoking lyrics — that pulls in a few different apples from the punk rock tree, from artsy to hardcore. Their multi-flavored sound maintains a ska vibe at times with its horn section and other times those noisemakers lend themselves to help bust out garage rock dripping with the spirit of the ‘60s. The band are constantly on the road and will kick off the second leg of their US tour in Denver, Colorado on May 2nd. You can catch them this weekend before they leave town at the Yucca Tap Room. ORDER "LOBOTOMOBILE" ORDER LIMITED COLORED VINYL of "DONT LET IT BE" US TOUR DATES: -

Fenway Park, Then Visit the Yankees at New Yankee Stadium

ISBN: 9781640498044 US $24.99 CAN $30.99 OSD: 3/16/2021 Trim: 5.375 x 8.375 Trade paperback CONTENTS HIT THE ROAD ..................................................................... 00 PLANNING YOUR TRIP ......................................................... 00 Where to Go ........................................................................................................... 00 When to Go ............................................................................................................. 00 Before You Go ........................................................................................................ 00 TOP BALLPARKS & EXPERIENCES ..................................... 00 The East Coast ....................................00 The East Coast Road Trip .....................................................................................00 Boston W Red Sox .................................................................................................00 New York W Yankees and Mets .........................................................................00 Philadelphia W Phillies ........................................................................................ 00 Baltimore W Orioles ..............................................................................................00 Washington DC W Nationals ............................................................................. 00 Florida and the Southeast ........................00 Florida and the Southeast Road Trip ..............................................................00 -

Dropkick Murphys Streaming Outta Fenway Presented by Pega

Date: June 3, 2020 Dropkick Murphys Streaming Outta Fenway Presented By Pega Raises Over $700,000 For Charities Free May 29 Streaming Performance From Fenway Park Infield Featured Special 2-Song “Double Play” With Longtime Friend Bruce Springsteen Viewed Over 9 Million Times By People Around The World Event Marked First-Ever Music Event Without In-Person Audience At Major U.S. Venue And First Music Performance On Fenway Park’s Baseball Diamond New Dropkick Murphys Album & World Tour Planned For 2021 Dropkick Murphys returned to Boston’s most famous stomping grounds on Friday, May 29 for their free live streaming concert, Streaming Outta Fenway, presented by Pega. Following the success of the band’s free Streaming Up From Boston St. Patrick’s Day performance, Streaming Outta Fenway marked the first-ever music event without an in-person audience at a major U.S. venue, and the first music performance directly on the infield at Boston’s legendary Fenway Park. During the show, the band was joined remotely by longtime friend Bruce Springsteen for a special two song “Double Play” that included Dropkick Murphys’ “Rose Tattoo” and Springsteen’s “American Land.” Streaming Outta Fenway raised over $700,000 and counting for charities Boston Resiliency Fund, Feeding America®, and Habitat for Humanity, Greater Boston, with the help of fans and a generous $51,000 donation and $100,000 matching pledge from Pega. Viewed over 9 million times by people worldwide, the concert streamed concurrently on Dropkick Murphys’ Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Twitch pages, aired live on SiriusXM’s E Street Radio channel, and also streamed via RedSox.com, MLB.com, NESN.com, USO, Vulture and more. -

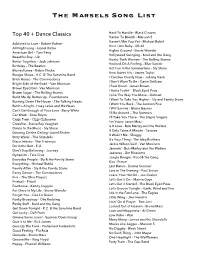

Marsels Song List 2015

The Marsels Song List Hard To Handle - Black Crowes Top 40 + Dance Classics Harder To Breath – Maroon 5 Haven’t Met You Yet – Michael Bublé Addicted to Love - Robert Palmer Here I Am Baby - UB 40 All Night Long – Lionel Richie Higher Ground - Stevie Wonder American Girl – Tom Petty Hollywood Swinging - Kool and the Gang Beautiful Day – U2 Honky Tonk Woman – The Rolling Stones Better Together – Jack Johnson Hooked On A Feeling – Blue Swede Birthday – The Beatles Hot Fun In the Summertime - Sly Stone Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke How Sweet It Is – James Taylor Boogie Shoes – K.C. & The Sunshine Band I Can See Clearly Now – Johnny Nash Brick House - The Commodores I Don’t Want To Be – Gavin DeGraw Bright Side of the Road – Van Morrison I Feel Good - James Brown Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison I Gotta Feelin’ – Black Eyed Peas Brown Sugar – The Rolling Stones I Like The Way You Move – Outkast Build Me Up Buttercup - Foundations I Want To Take You Higher – Sly and Family Stone Burning Down The House – The Talking Heads I Want You Back - The Jackson Five But It’s Alright - Huey Lewis and the News I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Can’t Get Enough of Your Love - Barry White I’ll Be Around – The Spinners Car Wash - Rose Royce I’ll Take You There - The Staple Singers Crazy Train – Ozzy Ozbourne I’m Yours- Jason Mraz Crossfire - Stevie Ray Vaughan Is It Love - Bob Marley and the Wailers Dance to the Music - Sly Stone It Only Takes A Minute - Tavares Dancing On the Ceiling- Lionel Ritchie It Wasn’t Me - Shaggy Dirty Water – The Standells It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers Disco Inferno - The Trammps Jackie Wilson Said - Van Morrison Do'in the Butt - E.U. -

PDF (V.68:16 February 2, 1967)

Bet you It/s Ground Hog didn/t know --- CaliforniaTech Day today! Associated Students of the California Institute of Technology Volume LVIII. Pasadena, California, Thursday, February 2, 1967 Number 16 Special By-laws Vote! Lilly Talks on AlDendlDent Would Allow So,ph-Jr Prexy Interlocution Monday night's BOD meeting 270 signees quickly surpassed the expressed hope that candidates from running. Fleming's Randy saw the introduction of a peti required 25% of the student would learn more about their of Harslem thinks there should be tion initiated by Joe Rhodes, to body. The sheets were headed fice if they were contested. no limitations since few enough With Dolphins the effect that over 270 members with the names of the seven Dabney's John Eyler blandly people are running as it is. of ASCIT feel that sophomores House presidents as Well as oth expressed agreement with the Ben Cooper, Blacker president Dr. John C. Lilly lectured to a should be allowed to run for the er student notables' and Meo. reasons stated on the petition, who introduced the petition into capacity crowd in Beckman Aud offices of ASCIT president and When interviewed, the House but admitted he was not per the meeting, feels that there is itorium Monday night on at vice-president. This petition re presidents gave varying reasons sonally satisfied with the current probably more political talent in tempts by man to communicate quests a revision of the By-laws for signing. candidates. the sophomore class than in the with dolphins. The author of of the Corporation, and thus ne Greg Shuptrine of' Ruddock Tony Gharrett, Ricketts House junior class, but that a junior the book Man and Dolphin men cessitates a vote by the Corpora feels that the present "dynamic" Prexy, signed purely to give the would be elected in most cases tioned that he was happy to re tion at large. -

ARSC Journal

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF DISCOGRAPHIES ANNUAL CUMULATION --- 1974 Edited by Michael Gray and Gerald Gibson INTRODUCTION For some time now virtually every user of discographies, regardless of subject, has agreed upon the need for a comprehensive bibliography of discographies. It was generally conceded, however, that the difficulty of attempting such a diversified bibliographic project was so great that it would be impossible for one or two people to attempt. A~er due consideration and some preliminary work (a number of you are probably aware of inquiries made by the editors of this bibliography in the periodical literature covering the field of sound recordings), we proceeded to contact several persons with strong discographic reputations in their respective subject fields to ask if they would be interested in working with us to produce a comprehensive bibliography of discographies to be pub lished annually in the ARSC Journal. In each instance we met with overwhelming enthusiasm and, as the following bibliography will attest, we have received marvelous co-operation. The contributors and their subject areas are: Country and Hillbilly--Norm Cohen, Playa del Ray, California; Blues-Gospel- David Evans, Anaheim, California; Spoken Documentary Recordings- Gary Shivers, Lawrence, Kansas; Jazz--Daniel Allen, Toronto, Canada, with the assistance of the late Walter C. Allen and of Steven Holzer of Indianapolis; and Classical--Michael Gray and Gerald Gibson, Washington, D. C. A recent addition to the "stable" in the area of Rock is Steve Smolian, Catskill, New York. As you can see, the areas of Folk, Ethnic and Popular Soul have not been covered in this bib liography; it is hoped that this oversight will be rectified in the near future. -

For the Love of Charles | XA00048

Application Note YSI Systems & Services • XA00048 For the Love of Charles FAMOUS “DIRTY WATER” IS ON THE REBOUND To rock ‘n roll fans of a certain age—and Boston sports fans celebrating points with a verse or two of The Standells’ 1966 hit “Dirty Water”— the Charles River is synonymous with pollution. On its way to Boston Harbor, the 80-mile-long river winds through one of America’s oldest industrial regions, supplying water, power and drainage to the hub of Massachusetts’ economy for more than 350 years. As the Bay State’s economy soared in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, water quality in the Charles experienced a steady decline. Slowed even further by a string of 20 dams installed before the end of the 1800s, its naturally sluggish flow ground nearly to a halt while pollution flowed in from the textile mills, factories and cities along its banks. In 1875, the The Charles River became so polluted, that in 1875 government recommended abandoning cleanup efforts in areas. federal government recommended abandoning clean-up efforts on [Photo from CRWA.] the lower half of the river and focusing instead on the upper reach. By the middle of the 20th century, combined sewer overflow (CSO) from Boston and Cambridge turned the Charles into a gutter during storms— an annual average of 28 CSO events and more than 1.7 billion gallons of combined discharge. But in 1965, just months before the release of “Dirty Water” stamped the Charles with its grungy identity, a group of locals banded together to turn the river’s fortunes around. -

Songs About U.S. Cities

Songs about U.S. Cities Here’s the 30-page list I compiled from Wikipedia: Abilene Abilene by George Hamilton IV Akron My City Was Gone by The Pretenders Downtown (Akron) by The Pretenders Albuquerque Albuquerque by Weird Al Yankovic Point Me in the Direction of Albuquerque by Tony Romeo Albuquerque by Neil Young Albuquerque by Sons of the Desert Bring Em Out by T.I. The Promised Land Chuck Berry Space Between Us Sister Hazel By the Time I Get to Phoenix Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Roger Miller Train Kept A Rollin' Stray Cats Wanted Man Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Nick Cave Blue Bedroom Toby Keith Get Your Kicks on Route 66 Perry Como Cowboy Movie David Crosby Make it Clap Busta Rhymes Allentown Allentown by Billy Joel Allentown Jail by Kingston Trio Amarillo Is This the Way to Amarillo by Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield Amarillo by Morning by George Strait If Hollywood Don't Need You (Honey I Still Do) by Don Williams Amarillo Sky by Jason Aldean Anchorage Anchorage by Michelle Shocked Atlanta ATL alt. rock song by Butch Walker, from Sycamore Meadows 2008 Atlanta Lady by Marty Balin (of Jefferson Airplane) Atlanta by Stone Temple Pilots, from No. 4 1999 Atlanta Burned Again Last Night by country group Atlanta, from Pictures 1983 Bad Education by Tilly and the Wall 2006 Badstreet U.S.A by Michael Hayes (wrestler) 1987 Communicating Doors by The Extra Lens (From Undercard, 2010) Hot 'Lanta (instrumental) by The Allman Brothers, from At Fillmore East 1971 F.I.L.A (Forever I Love Atlanta) by Lil Scrappy feat. -

2000 Sun. N0.3-45

EVEN AFTER 40 YEARS, GARAGE ROCK IS STILL ROARING (Continued from page 5) thanks to tinkering, tune -ups, and gins, never really disappeared. Still, viable garage rock enjoys just finished three laps of the coun- What may have been "guy carloads of reissue treasures, the "It's always been there, but it's "very little" support at radio and try and went from playing to three music" then "ain't just guy music music these bands made continues no longer a tiny niche. [It's] retail, notes Weiss, "other than ran- or four people at some gigs in May notes Irwin. Nor is garage to enjoy a strong following and to groundswelled to the point where dom college radio programming, to headlining rooms on the West rock solely an American institution steadily influence musicians today. it influences contemporary music to maybe another W or two every Coast that we couldn't even get a any more. Gregg Kostelich, head of Labels like Rhino Records, Sun- amazing degree," says Irwin. now and then who loves this stuff, date in six months earlier," he says. Pittsburgh's Get Hip garage -rock dazed Music, ROIR Records, Ace Every" time I walk by my teenage and scattered specialty shops. You "But we always play fora group of label and distributor and guitarist Records, Cavestomp! Records, daughter's bedroom and hear what go to a Tower [Records store] and people in a city who knows every- for the label's group the Cynics, was Norton Records, Telstar Records, she's listening to, f pause and count e a lot of this music lumped into "else in the last city we were just surprised to draw 5,000 people dur- Bomp! Records, Estrus Records, the influences: 'Boy! That electric the oldies section, but that goes in. -

1 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E 1F 1G

P050-063_Discography1-JUN14_Lr2_qxd_P50-63 6/24/14 9:57 PM Page 50 {}MIKE CURB : 50 Years DISCOGRAPHY Titanic Records was the first label to release a song by existing record label did not initially release “War Path.” For “SPEEDWAY” ARTIST : THE Mike Curb’s group. “Our band was willing to work under this reason, Mike – with the encouragement of his friend 1HEYBURNERS WRITER: MIKE CURB any name,” Mike says. “In those days, record companies and fellow songwriter Mary Dean – created a new label PUBLISHER: GOLD BAND MUSIC (BMI) wanted to have names they could continue to use if the using the first two letters of both of their names (Cude). TIME: 2:23 PRODUCER: MIKE CURB THANKS: record was a hit. Our band didn’t want to get locked into Shortly after it was released on Cude, the record received DEAN-SALERNO TITANIC 5009, 1962 any one record company, so we let any company we worked local radio airplay and caught the attention of Marc Records. with name us whatever they wanted to name us.” Titanic “Slipstream,” released on Dot under the name The “WAR PATH” ARTIST: DAVIE ALLAN chose to call the group The Heyburners and released Streamers, is another example of a young Mike Curb 1WA RITER: DAVIE ALLAN, MIKE CURB “Speedway,” a song Mike had written. writing and performing an instrumental. This record PUBLISHER: ARROW DYNAMIC MUSIC captures the energy of young, hip southern California (BMI)/MIKE CURB MUSIC (BMI) TIME: 2:04 before the rest of the country caught on to that sound, PRODUCER: MIKE CURB SPECIAL THANKS: { 1964 { through guitar groups like The Ventures.