Chess Tactics for the Tournament Player

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

+P+-+K+- +-+-+-+- B -+-+P+-+ W -+-+-+-+ Zlw-+P+R +-+-+-Z- P+-+N+Q+ P+-+-+-+ +-+-+-+- Z-+K+-+- -+-+-TP+ Kwqs-Z-S +-+-+RM- +-+-+-+

Contents Symbols 4 Introduction 5 Part 1: The Basics 1 Pin 7 2 Deflection 16 3 Overload 23 4 Decoy 28 5 Double Attack 36 6 Knight Fork 44 7 Discovered Attack 50 8 Clearance 56 9 Obstruction 64 10 Removing the Defender 71 11 The Power of the Pawn 77 12 Back-Rank Mate 85 13 Stalemate 91 14 Perpetual Check and Fortresses 96 Part 2: Advanced Tactics 15 f7: Weak by Presumption 103 16 The Vulnerable Rook’s Pawn 111 17 Attacking the Fianchetto 118 18 The Mystery of the Opposite-Coloured Bishops 125 19 Chess Highways: Open Files 131 20 Trapping a Piece 141 21 Practice Makes Perfect 149 Solutions 158 Index of Players 188 Index of Composers 191 KNIGHT FORK 6 Knight Fork The knight is considered to be the least powerful White is now a queen and two rooks down – piece in chess (besides the pawn, of course). As a deficit of approximately 19 ‘pawns’. His only the great world champion Jose Raul Capablanca remaining piece is a knight. But a brave one... taught us, the other minor piece, the bishop, is 3 Ìe3+ Êf6 4 Ìxd5+ Êf5 5 Ìxe7+ Êf6 6 better in 90% of cases. However, due to its spe- Ìxg8+ (D) cific qualities the knight is a tremendously dan- gerous piece. It is nimble and its jumps can be -+-+-+N+ quite shocking. That is why a double attack by a +-+-+p+- knight is usually distinguished from other dou- B ble attacks and called a fork. -+-+nm-M +-+-z-+- A single knight may cause incredible dam- age in the right circumstances: -+-+-+-+ +-+-+PZ- -+-+-+q+ -+-+-+-+ +-+r+p+- +-+-+-+- W -+N+nm-M +-+rz-+- The knight has managed to remove most of Black’s army. -

248 Cmr: Board of State Examiners of Plumbers and Gas Fitters

248 CMR: BOARD OF STATE EXAMINERS OF PLUMBERS AND GAS FITTERS 248 CMR 10.00: UNIFORM STATE PLUMBING CODE Section 10.01: Scope and Jurisdiction 10.02: Basic Principles 10.03: Definitions 10.04: Testing and Safety 10.05: General Regulations 10.06: Materials 10.07: Joints and Connections 10.08: Traps and Cleanouts 10.09: Interceptors, Separators, and Holding Tanks 10.10: Plumbing Fixtures 10.11: Hangers and Supports 10.12: Indirect Waste Piping 10.13: Piping and Treatment of Special Hazardous Wastes 10.14: Water Supply and the Water Distribution System 10.15: Sanitary Drainage System 10.16: Vents and Venting 10.17: Storm Drains 10.18: Hospital Fixtures 10.19: Plumbing in Manufactured Homes and Construction Trailers 10.20: Public and Semi-public Swimming Pools 10.21: Boiler Blow-off Tank 10.22: Figures 10.23: Vacuum Drainage Systems 10.01: Scope and Jurisdiction (1) Scope. 248 CMR 10.00 governs the requirements for the installation, alteration, removal, replacement, repair, or construction of all plumbing. (2) Jurisdiction. (a) Nothing in 248 CMR 10.00 shall be construed as applying to: 1. refrigeration; 2. heating; 3. cooling; 4. ventilation or fire sprinkler systems beyond the point where a direct connection is made with the potable water distribution system. (b) Sanitary drains, storm water drains, hazardous waste drainage systems, dedicated systems, potable and non-potable water supply lines and other connections shall be subject to 248 CMR 10.00. 10.02: Basic Principles Founding of Principles. 248 CMR 10.00 is founded upon basic principles which hold that public health, environmental sanitation, and safety can only be achieved through properly designed, acceptably installed, and adequately maintained plumbing systems. -

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

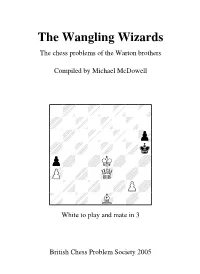

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev by Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All Rights Reserved

Correspondence Chess News Issue 31 - 14 January 2001 An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev By Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All rights reserved. How did you first get attracted to chess? Please also say something about your early chess development in Ukraine. I started to play in 1976 (at the age of six) and from 1977 onwards, I started to learn chess in the chess club (by the way, many players the world over think that chess was an obligatory discipline in the regular Soviet Schools – that’s not correct). Sometimes, I think that I started to look at chess seriously after my parents got divorced, but I’m not sure if it was the real impetus. In any case, I was quite able to play chess. It is easy to say as I scored many good results, especially at the age of 12-14 years. For instance, in the 1984 (at age 14), I shared second place (with the better tiebreak) with Ivanchuk (he was one year older) in the Ukrainian Junior Ch U- 17. Still, I’m not sure if I’m a born chess player. I remember, in 1984 I played in a junior tournament in Baku, and shared the first place there with Vladimir Akopian. Volodya is one year younger than me, and he was very small in 1984 J . We played an extremely complicated game, and I accepted his draw offer when my position was already better. I was quite afraid for him, as for the first time I saw a clearly more talented player than me. -

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712 Congratulations on your purchase of Excalibur Electronics’ IVAN! You’ve purchased both your own personal chess trainer and a partner who’s always ready for a game—and who can improve as you do! Talking and audio sounds add anoth- Play a Game Right Away er dimension to your IVAN computer for After you have installed the batteries, the increased enjoyment and play value. display will show the chess board with all the pieces on their starting squares. Place Find the Pieces the plastic chess pieces on their start Turn Ivan over carefully with his chess- squares using the LCD screen as a guide. board facedown. Find the door marked The dot-matrix display will show “PIECE COMPARTMENT DOOR”. 01CHESS. This indicates you are at the Open it and remove the chess pieces. first move of the game and ready to play Replace the door and set the pieces aside chess. for now. Unless you instruct it otherwise, IVAN gives you the White pieces—the ones at Install the Batteries the bottom of the board. White always With Ivan facedown, find the door moves first. You’re ready to play! marked “BATTERY DOOR’. Open it and insert four (4) fresh, alkaline AA batteries Making your move in the battery holder. Note the arrange- Besides deciding on a good move, you ment of the batteries called for by the dia- have to move the piece in a way that Ivan gram in the holder. Make sure that the will recognize what's been played. Think positive tip of each battery matches up of communicating your move as a two- with the + sign in the battery compart- step process--registering the FROM ment so that polarity will be correct. -

ENDING the ENERGY STALEMATE a Bipartisan Strategy to Meet America’S Energy Challenges

ENDING THE ENERGY STALEMATE A Bipartisan Strategy to Meet America’s Energy Challenges THE NATIONAL COMMISSION ON ENERGY POLICY December 2004 Cover: U.S. Government Satellite Images: Western Hemisphere at Night ENDING THE ENERGY STALEMATE A Bipartisan Strategy to Meet America’s Energy Challenges THE NATIONAL COMMISSION ON ENERGY POLICY December 2004 www.energycommission.org PREAMBLE This report is a product of a bipartisan Commission of 16 members of diverse expertise and affiliations, addressing many complex and contentious topics. It is inevitable that arriving at a consensus document in these circumstances entailed innumerable compromises. Accordingly, it should not be assumed that every member is entirely satisfied with every formulation in the report, or even that all of us would agree with any given recommendation if it were taken in isolation. Rather, we have reached consensus on the report and its recommendations as a package, which taken as a whole offers a balanced and comprehensive approach to the economic, national security, and environmental challenges that the energy issue presents to our nation. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Commission on Energy Policy was founded in 2002 by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and its partners: The Pew Charitable Trusts, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Energy Foundation. The Commission would like to express its sincere appreciation for the Hewlett Foundation’s vision and the strong support of its partners. The Commission would also like to thank the following Commissioner representatives for their many contributions to the Commission’s ongoing work and to this report: Gordon Binder, Principal, Aqua International Partners; Kelly Sims Gallagher, Director, Energy Technology Innovation Project, Belfer Center for Science & International Affairs, Harvard University; Marianne S. -

Aron Nimzowitsch My System & Chess Praxis

Aron Nimzowitsch My System & Chess Praxis Translated by Robert Sherwood New In Chess 2016 Contents Translator’s Preface............................................... 9 My System Foreword..................................................... 13 Part I – The Elements . 15 Chapter 1 The Center and Development...............................16 1. By development is to be under stood the strategic advance of the troops to the frontier line ..............................16 2. A pawn move must not in and of itself be regarded as a develo ping move but should be seen simply as an aid to develop ment ........................................16 3. The lead in development as the ideal to be sought ..........18 4. Exchanging with resulting gain of tempo.................18 5. Liquidation, with subsequent development or a subsequent liberation ..........................................20 6. The center and the furious rage to demobilize it ...........23 7. On pawn hunting in the opening ......................28 Chapter 2 Open Files .............................................31 1. Introduction and general remarks.......................31 2. The origin (genesis) of the open file ....................32 3. The ideal (ultimate purpose) of every operation along a file ..34 4. The possible obstacles in the way of a file operation ........35 5. The ‘restricted’ advance along one file for the purpose of relin quishing that file for another one, or the indirect utilization of a file. 38 6. The outpost .......................................39 Chapter 3 The Seventh and Eighth Ranks ..............................44 1. Introduction and general remarks. .44 2. The convergent and the revo lutionary attack upon the 7th rank. .44 3. The five special cases on the seventh rank . .47 Chapter 4 The Passed Pawn ........................................75 1. By way of orientation ...............................75 2. The blockade of passed pawns .........................77 3. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Super Human Chess Engine

SUPER HUMAN CHESS ENGINE FIDE Master / FIDE Trainer Charles Storey PGCE WORLD TOUR Young Masters Training Program SUPER HUMAN CHESS ENGINE Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Power Principles...................................................................................................................................... 4 Human Opening Book ............................................................................................................................. 5 ‘The Core’ Super Human Chess Engine 2020 ......................................................................................... 6 Acronym Algorthims that make The Storey Human Chess Engine ......................................................... 8 4Ps Prioritise Poorly Placed Pieces ................................................................................................... 10 CCTV Checks / Captures / Threats / Vulnerabilities ...................................................................... 11 CCTV 2.0 Checks / Checkmate Threats / Captures / Threats / Vulnerabilities ............................. 11 DAFiii Attack / Features / Initiative / I for tactics / Ideas (crazy) ................................................. 12 The Fruit Tree analysis process ............................................................................................................ -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”.