Private Managed Forest Program Review - Joint ENGO Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder for Immediate Release: December 10, 2015

Backgrounder For Immediate Release: December 10, 2015 Conservationists Call for Innovative Fund to Buy New Parks Victoria, BC – Conservationists are calling on the BC government to establish a Fund for Nature’s Future. In a new report prepared for the Ancient Forest Alliance, the UVic Environmental Law Centre (ELC) ELC is calling on the Province to establish an annual $40 million Natural Lands Acquisition Fund to purchase and protect endangered ecosystems on private lands. The report, Finding the Money to Buy and Protect Natural Lands, provides a “menu” of possible ways that funds can be allocated or generated for a dedicated fund to purchase vital green spaces and natural areas from willing sellers of private lands. These mechanisms include: • $10 to $15 million per year by simply recapturing the windfall that the beverage industry enjoys when consumers fail to redeem container deposits, an approach nicknamed “pops for parks”. • Many millions more could be raised by emulating the most important mechanism for park funding in the US – a special tax on non-renewable resources like oil and gas. Numerous North American governments have ruled that it is fair to require industries using up non-renewables to compensate future generations – and permanently protect other natural resources. • Funds from a tax on real estate speculation. Currently Vancouver real estate is becoming unaffordable because of speculation in the housing market. Some are proposing a specially designed tax to curb speculation. Fortuitously, such a speculation tax could provide generous funding for acquisition of natural areas – areas which will be needed to serve our growing population. -

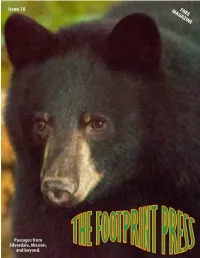

Footprint Press Issue 18

Issue 18 MAGAZINEFREE Passages from Silverdale, Mission, and beyond. Message from the Editorial Committee ll creatures, big and small, human and nonhuman, ulti- mately owe their lives to plants. The rooted ones provide Aus with the food we eat, the air we breathe, and the water we drink. Every morsel of our food is ultimately derived from plants, directly, or indirectly through other animals, which them- selves, ate plants. Forests are the lungs of the planet, releasing the oxygen for us to breathe, absorbing carbon dioxide, and thus create the atmosphere of the earth. Tall trees capture and condense clouds into rain, which replenishes streams, rivers and the aquifers, from which we derive our drinking water. And plant communities capture and hold moisture, slowly releasing it when needed most, thereby preventing desiccation of the soil, and sheltering a myriad of creatures nestled within their woody embrace. Our relationships with plants are complex, going back so many years that all animals and plants have the majority of their genes in common. The relationships between plants and other life forms are so pervasive and so fundamental, that we risk taking the rooted ones for granted. Ancient cedar trees are being lost at an alarming rate, with little regard for their sacred role in life’s complex tapestry. These ancient beings, which have survived 1000s of years, feed a hunger which will never be satiated, even after every last tree is gone. First Nations’ people understood the generosity of cedar trees and other plants. The DNA of wild salmon has been found in the tops of cedar trees, after the salmon were brought to the tree by bears, eagles and other animals. -

The Fight to Protect What's Left of Old

The fight to protect what’s left of old-growth forests Mark Hume VANCOUVER — The Globe and Mail Published Sunday, Mar. 17 2013, 10:18 PM EDT Last updated Sunday, Mar. 17 2013, 10:35 PM EDT Let’s forget about the end of oil for a moment and worry about something more immediate: the end of old-growth forests. British Columbia is the last place in Canada where you can still find ancient, monumental trees standing outside parks. We are not talking here just about big, old trees, but about trees 250 to 1,000 years old, that tower 70 metres in height. If one grew on the steps of Parliament, its tip would block out the clock face on the Peace Tower. And set down in Vancouver, they would be as tall as many office towers. Surprisingly, it is still legal in B.C. to cut down trees like that. And so many of these giants have been cut over the past 20 years, says Ken Wu of the Ancient Forest Alliance, that the end of old growth is near. “We’ve just about hit it already in the coastal Douglas-fir zone,” he said. “On eastern Vancouver Island, we’ve got 1 per cent of old growth left. On the south Island, south of Alberni, we’ve got about 10 per cent left.” Three years ago, Mr. Wu founded the Ancient Forest Alliance, a small group dedicated to just one task – saving old trees. Since then, he and his colleagues have spent a lot of time tramping around coastal forests, mapping groves of giant trees – and pleading with the government to protect them. -

Affidavit of Carolyne Brenda Sayers

Court File No. T-153-13 FEDERAL COURT BETWEEN: HUPACASATH FIRST NATION APPLICANT - and- THE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS CANADA as represented by THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENT APPLICA TION UNDER THE FEDERAL COURTS ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. F-7, s. 18.1 AFFIDAVIT OF CAROL YNE BRENDA SAYERS I, CAROL YNE BRENDA SAYERS, Council Member, of 5110 Indian Avenue, of the City of Port Albemi, Province of British Columbia, SWEAR THAT: 1. I am an elected Council member of the Hupacasath First Nation, and as such have personal knowledge of the facts and matters hereinafter deposed to, save and except where same are stated to be made on information and belief, and where so stated, I verily believe them to be true. The Hupacasath First Nation is also known as the Hupacasath Indian Band and formerly known as the Opetchesaht Indian Band. The Hupacasath Indian Band, is a "band" within the meaning of the term defined in the Indian Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 1-5 (the "Indian Ad'). 2. The Hupacasath Chief and Council represent approximately 285 band members and all band members are Indians as that term is defined by the Indian Act. I am a member of the Hupacasath First Nation and as such have knowledge of our territory, history, use of our territory and the exercise of our rights. - 2 - 3. I am authorized by the Chief and Council to swear this affidavit on behalf of the Hupacasath First Nation. 4. The Hupacasath territory consists of approximately 232,000 hectares in and beyond the Alberni Valley on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. -

Driving Directions to the Avatar Grove, Red Creek Fir, San Juan Spruce, & Big Lonely Doug!

Driving directions to the Avatar Grove, Red Map by Geoffrey Senichenko. Photos by TJ Watt. Directions to Big Lonely Doug Reproduced by the Ancient Forest Alliance in 2017. (continued from Avatar Grove Direction #7 - on left) Creek Fir, San Juan Spruce, & Big Lonely Doug! For more local info visit: www.RenfrewChamber.com 8. Continue past the Avatar Grove on the Gordon River Main ***The Ancient Forest Alliance, its staff, and directors, assume no liability for one’s for approximately 5 km and take your FIRST RIGHT onto ort Renfrew, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, is ‘Canada’s Tall Avatar Grove is filled with some of Canada’s largest western redcedars safety or belongings while driving or hiking and using this map or directions as a guide. Edinburgh Main. This a narrower looking road. Tree Capital’. Close to this charming little sea-side town grows the and Douglas-firs. Many of the cedars have massive, odd-shaped “burls” These are remote wilderness areas - travel and hike at your OWN RISK!! 9. Soon afterwards you will reach a bridge over a very deep growing on their trunks, including “Canada’s Gnarliest Tree” in the Upper Pworld’s largest Douglas-fir tree, the massive Red Creek fir, as well canyon on the Gordon River. (*Note: Vehicles with 4wd and as the newly found “Big Lonely Doug”, Canada’s second largest Douglas- Avatar Grove. The local Pacheedaht First Nation’s traditional name for Directions to Avatar Grove fir. They are wonders to behold. En route to the Red Creek Fir is one of the area is ‘T’l’oqwxwat’, meaning “wide bluff overlooking river”. -

Is a Club That

Club Name Club Email Address Description ABS [email protected] The ABS club (Association for Baha’i studies) is a club that allows Baha’i students and faculty (as well as any one else interested) to aid one another in meaningful service to our campus community as well as reflect on how we can coherently integrate our spiritual beliefs and academic study. This club hopes to hold dinners, reflections, devotional meetings to increase a sense of community and engage in conversation around deeper and spiritual topics. African and Caribbean [email protected] African-Caribbean Students' Association (ACSA) was founded to Students' Association increase cultural awareness and communal cohesion on the University of Victoria campus between the African and Carribean communities and the local Victoria community AIESEC [email protected] AIESEC is a youth leadership development organization that puts students in practical team experiences to challenge their skills. We facilitate global volunteer and work internships in various fields for students to gain practical working experiences. AIESEC works towards the 17 Sustainable Development goals created by the United Nations. AKCSE (Association of [email protected] This club welcomes Korean-Canadians who are in Science or Korean-Canadians Scientists Engineering to build connections by studying together and and Engineers) socializing. Every university in Canada has AKCSE and the presidents of the club write reports and meet up once a year to discuss ideas to develop relationships for the students relating to their future jobs. Since a lot of students in the club are 1.5 generations, they have hard times finding connections. -

Ancient Forest Alliance Formal Submission

Ancient Forest Alliance Victoria Main PO Box 8459 Victoria BC V8W 3S1 Tel: 250-896-4007 Email: [email protected] Submission to the Old Growth Strategic Review with Recommendations for BC’s Old Growth Strategy Prepared by the Ancient Forest Alliance January 31, 2020 The Ancient Forest Alliance (AFA) is a registered non-profit organization representing tens of thousands of BC residents who support science-based protection of BC’s endangered old-growth forests and an expedited shift to a sustainable, value-added second-growth forest industry in the province. Rationale We welcome the BC government’s commitment to develop a provincial Old Growth Strategy and urge the Old Growth Strategic Review panel to recommend meaningful steps to increase protection of endangered forest ecosystems. BC’s old-growth forests are complex ecosystems that have evolved over millennia and are home to some of the largest and oldest trees on Earth. They provide habitat for unique and threatened species, support clean water for communities and wild salmon, store more carbon per hectare than second- growth forests, are a pillar of BC’s multi-billion dollar tourism industry, and are vital to many First Nations cultures, whose unceded lands these are. A century of industrialized logging has resulted in over 75 per cent of the original, productive old-growth forests being logged on BC’s southern coast, including well over 90 per cent of the valley bottoms where the richest biodiversity and largest trees are found.1,2 Old-growth is a non-renewable resource under BC’s system of forestry where second-growth forests are logged every 50-80 years, never to become old again. -

{AT RISK} Cathedral Grove and Old-Growth Forests on Central Vancouver Island

{AT RISK} Cathedral Grove and Old-Growth Forests on Central Vancouver Island athedral Grove on Vancouver Island is Canada’s A total of 2400 hectares of these areas were originally intended most famous old-growth forest. Millions of people for protection by the BC government, upon recommendation from around the world have come to marvel at its by their biologists, as Ungulate Winter Ranges (UWR) to Cawe-inspiring, 800 year old Douglas-fir trees, located within safeguard deer and/or elk wintering habitat, or as Wildlife MacMillan Provincial Park near Port Alberni. Habitat Areas (WHA) for the endangered Queen Charlotte goshawk. However, the company’s logging in recent years has However, few people know that right now Cathedral Grove reduced these remaining forests now to perhaps one-third of is under major threat, as Island Timberlands has built a road their original extent. onto the mountainside above the park on Mount Horne in preparation for logging. The logging would threaten Cathedral Grove’s ecological integrity by increasing erosion and siltation from the new cutblock above the grove; destroying critical wildlife habitat and the endangered old-growth Douglas-fir forest on the slope that is contiguous with Cathedral Grove; and degrading the area’s recreational opportunities by ruining parts of the Mount Horne Loop Trail, a popular hiking and mushroom picking trail that is accessed from the Cathedral Grove parking lot. Find more info at SaveCathedralGrove.com Island Timberlands is also building roads and/or logging in other endangered old-growth forests on central Vancouver Island, including at McLaughlin Ridge in Port Alberni’s drinking watershed; the Cameron Valley Firebreak upstream Top - Cathedral Grove’s world-famous old-growth Douglas-firs are on the flats in the foreground, while Mount Horne, from Cathedral Grove; Katlum Creek near Courtenay; and the mountainside above the park, is threatened with logging by Island Timberlands on its currently intact slope. -

Summer 2020 Issue of the Watershed Sentinel

Summer 2020 Newstand Price $4.95 Summer 2020 Sentinel Summer 2020 Vol. 30 No. 3 Features 14 18 ©Illustration compiled by Sarah James Sarah by compiled ©Illustration ©wJacek Dylag Poison Pipes COVID-19 and the Environment Canada’s legacy of old, deteriorating Add one tiny deadly virus to one massive, globalized, unequal, extractive economy; asbestos cement water mains has been mix well on a limited and stressed planet. This section delves into disaster capitalism, getting shoved under the rug for decades. the future of fossil fuels, globalization, farm survival – and the possibilities of change. Content 3,5 News Shorts 10 Dicamba 34 Rats & Mice Pellets, pipelines, divestment, US courts de-register a Rodent lessons on shareholder power, & more... massively damaging pesticide overpopulation and social breakdown 6 Fracking & Dams 11 Ancient Trees Union of BC Indian Chiefs calls Recent logging in BC shows 36 Wild Times for a moratorium protection is becoming urgent Will BC release the Old Growth Strategic Review findings 7 Teztan Biny 29 Silver Linings anytime soon? Taseko’s zombie mine is finally, From elder pirate radio to officially, legally dead Europe’s green recovery plan Cover Credit: 8 Firestarter 32 Planet of Yahoos ©Illustration compiled by Sarah James Powell River startup is a social Film review: is looking at plan- & environmental win-win etary limits... off limits? Printed on Rolland EnviroPrint, 100% post-consumer Process Chlorine Free recycled fibre, FSC, Ecologo and PCF certified. watershedsentinel.ca | 1 Editorial Sentinel Delores Broten Publisher Watershed Sentinel Educational Society Editor Delores Broten Managing Editor Claire Gilmore Graphic Design Ester Strijbos The Light of Change Staff Reporter Gavin MacRae Renewals & Circulation Manager Dawn Christian We could see it on the horizon. -

Free Report Vancouver Island's

Vol.35 No.3 | 2016 Co-published by the Wilderness Committee & Sierra Club BC FREE REPORT VANCOUVER ISLAND'S IT’S TIME FOR ACTION IN VANCOUVER ISLAND’S FORESTS renewable resource, and leadership also play a critical role in BC’s multi- communities up and down the coast. from the provincial government is billion dollar tourism industry. Every year, these corporations send desperately needed to protect them. Perhaps most importantly, coastal millions of cubic metres of raw wood2 The profound importance temperate rainforests are among – enough to build more than 100,000 of Vancouver Island’s ancient the best carbon storehouses on the new homes3 – overseas without rainforests simply cannot be planet, and are some of our best adding any value here in BC. Torrance Coste Jens Wieting Vancouver Island Campaigner, Forest and Climate overstated. In these rare forests, assets in the fight against climate We need increased conservation Wilderness Committee Campaigner, Sierra Club BC thousand-year-old trees tower over change. Old-growth forests can of old-growth and other sensitive @TorranceCoste @JensWieting lush undergrowth, where diverse store more carbon than younger forests. But justice for forestry plant and animal species flourish. forests, keeping it out of the workers and the families and ancouver Island on Canada’s These intact ecosystems provide the atmosphere where it destabilizes communities they support must also Vwest coast has some of the most greatest abundance of traditional the climate and jeopardizes the be part of revamped forest policy on spectacular rainforest landscapes resources and medicines utilized by future of millions of people. Vancouver Island. -

Final Title Here

Alliance Forest Ancient n.d., Watt, TJ by Growth Old Grove Eden Economic Valuation of Old Growth Forests on Vancouver Island Phase 2 – Port Renfrew Pilot Study May 3, 2021 Prepared for: ESSA Technologies Ltd. 2695 Granville Street, Suite 600 Vancouver, BC, V6H 3H4 P: (604) 733-2996 E : [email protected] Economic Valuation of Old Growth Forests on Vancouver Island Phase 2 – Port Renfrew Pilot Study Prepared for: FINAL REPORT May 3, 2021 Ancient Forest Alliance Suggested Citation: Morton, C., R. Trenholm, S. Beukema, D. Knowler, R. Boyd. 2021. Economic Valuation of Old Growth Forests on Vancouver Island: Pilot Study; Phase 2 – Port Renfrew Pilot. ESSA Technologies Ltd. for the Ancient Forest Alliance. Vancouver, BC. Cover Image: “Eden Grove Old Growth”, by TJ Watt (n.d.), Ancient Forest Alliance ESSA Technologies Ltd. Vancouver, BC Canada V6H 3H4 www.essa.com Economic Valuation of Old Growth Forests on Vancouver Island, Phase 2 Table of Contents Summary of Results .................................................................................................................................. vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Site Selection ............................................................................................................................ -

BC Needs a Park Acquisition Fund!

BC Needs a Park Acquisition Fund! Cathedral Grove Canyon (see inside for details) Koksilah Ancient Forest – This exceptional tract of Mossy Maple Grove or “Fangorn Forest” – This A provincial fund of at least $40 million per year is needed to purchase monumental Douglas-firs along the Koksilah River near Shawnigan Lake is grove near Cowichan Lake of enormous old-growth bigleaf maple trees in the endangered Dry Maritime zone. It stands today because of two far- – some over 2.3 meters (7 feet) wide in trunk diameter – is completely BC’s most endangered ecosystems on private lands to sustain wildlife, sighted loggers who refused to log here in the 1980’s. Tourists from around draped in hanging gardens of mosses and ferns. Unlike other contentious the world come to marvel at this still-unprotected grove. The BC Investment old-growth forests that have all been “coniferous”, this is a very unique old- clean water, recreation and tourism. Management Corporation (BC IMC) and the federal Public Sector Investment growth “deciduous” or broad-leaf forest, home to elk, bears, and cougars. Management Board (PSIMB) bought the lands from TimberWest in 2011. The First Nations land use plan of the local Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group calls Contact Warrick and Jan Whitehead at: 250-748-1374 for the protection of the remaining old-growth forests in their territories. cross British Columbia many of our most endangered The BC IMC and PSIMB bought the lands from TimberWest in 2011. ALL PHOTOS BY TJ WATT ecosystems are found on private lands. These include the Contact the Ancient Forest Alliance at: [email protected] Coastal Douglas-fir and Dry Maritime forests on Vancouver What can I Do to Help Establish a BC PARK ACQUISITION FUND? IslandA and the Sunshine Coast, with their Mediterranean-like climates, twisted arbutus trees on rocky outcrops, and extremely 1.