Chicago School of Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago from 1871-1893 Is the Focus of This Lecture

Chicago from 1871-1893 is the focus of this lecture. [19 Nov 2013 - abridged in part from the course Perspectives on the Evolution of Structures which introduces the principles of Structural Art and the lecture Root, Khan, and the Rise of the Skyscraper (Chicago). A lecture based in part on David Billington’s Princeton course and by scholarship from B. Schafer on Chicago. Carl Condit’s work on Chicago history and Daniel Hoffman’s books on Root provide the most important sources for this work. Also Leslie’s recent work on Chicago has become an important source. Significant new notes and themes have been added to this version after new reading in 2013] [24 Feb 2014, added Sullivan in for the Perspectives course version of this lecture, added more signposts etc. w.r.t to what the students need and some active exercises.] image: http://www.richard- seaman.com/USA/Cities/Chicago/Landmarks/index.ht ml Chicago today demonstrates the allure and power of the skyscraper, and here on these very same blocks is where the skyscraper was born. image: 7-33 chicago fire ruins_150dpi.jpg, replaced with same picture from wikimedia commons 2013 Here we see the result of the great Chicago fire of 1871, shown from corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. This is the most obvious social condition to give birth to the skyscraper, but other forces were at work too. Social conditions in Chicago were unique in 1871. Of course the fire destroyed the CBD. The CBD is unique being hemmed in by the Lakes and the railroads. -

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013 2013 Lake Baha’i Glenview 41 Wilmette Temple Central Old 14 45 Orchard Northwestern 294 Waukegan Golf Univ 58 Milwaukee Sheridan Golf Morton Mill Grove 32 C O N T E N T S Dempster Skokie Dempster Evanston Des Main 2 Getting Around Plaines Asbury Skokie Oakton Northwest Hwy 4 Near the Hotels 94 90 Ridge Crawford 6 Loop Walking Tour Allstate McCormick Touhy Arena Lincolnwood 41 Town Center Pratt Park Lincoln 14 Chinatown Ridge Loyola Devon Univ 16 Hyde Park Peterson 14 20 Lincoln Square Bryn Mawr Northeastern O’Hare 171 Illinois Univ Clark 22 Old Town International Foster 32 Airport North Park Univ Harwood Lawrence 32 Ashland 24 Pilsen Heights 20 32 41 Norridge Montrose 26 Printers Row Irving Park Bensenville 32 Lake Shore Dr 28 UIC and Taylor St Addison Western Forest Preserve 32 Wrigley Field 30 Wicker Park–Bucktown Cumberland Harlem Narragansett Central Cicero Oak Park Austin Laramie Belmont Elston Clybourn Grand 43 Broadway Diversey Pulaski 32 Other Places to Explore Franklin Grand Fullerton 3032 DePaul Park Milwaukee Univ Lincoln 36 Chicago Planning Armitage Park Zoo Timeline Kedzie 32 North 64 California 22 Maywood Grand 44 Conference Sponsors Lake 50 30 Park Division 3032 Water Elmhurst Halsted Tower Oak Chicago Damen Place 32 Park Navy Butterfield Lake 4 Pier 1st Madison United Center 6 290 56 Illinois 26 Roosevelt Medical Hines VA District 28 Soldier Medical Ogden Field Center Cicero 32 Cermak 24 Michigan McCormick 88 14 Berwyn Place 45 31st Central Park 32 Riverside Illinois Brookfield Archer 35th -

333 North Michigan Buildi·N·G- 333 N

PRELIMINARY STAFF SUfv1MARY OF INFORMATION 333 North Michigan Buildi·n·g- 333 N. Michigan Avenue Submitted to the Conwnission on Chicago Landmarks in June 1986. Rec:ornmended to the City Council on April I, 1987. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development J.F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner 333 NORTH MICIDGAN BUILDING 333 N. Michigan Ave. (1928; Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root) The 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING is one of the city's most outstanding Art Deco-style skyscrapers. It is one of four buildings surrounding the Michigan A venue Bridge that defines one of the city' s-and nation' s-finest urban spaces. The building's base is sheathed in polished granite, in shades of black and purple. Its upper stories, which are set back in dramatic fashion to correspond to the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, are clad in buff-colored limestone and dark terra cotta. The building's prominence is heightened by its unique site. Due to the jog of Michigan Avenue at the bridge, the building is visible the length of North Michigan Avenue, appearing to be located in the center of the street. ABOVE: The 333 North Michigan Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, which encouraged the construction of buildings with setback towers. This photograph was taken from the cupola of the London Guarantee Building. COVER: A 1933 illustration, looking south on Michigan Avenue. At left: the 333 North Michigan Building; at right the Wrigley Building. 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING 333 North Michigan Avenue Architect: Holabird and Roche/Holabird and Root Date of Construction: 1928 0e- ~ 1QQ 2 00 Cft T Dramatically sited where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River are four build ings that collectively illustrate the profound stylistic changes that occurred in American architecture during the decade of the 1920s. -

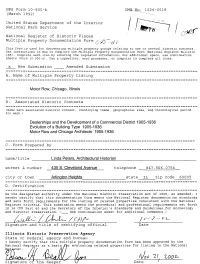

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois Street

NFS Form 10-900-b OMR..Np. 1024-0018 (March 1992) / ~^"~^--.~.. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / / v*jf f ft , I I / / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form /..//^' -A o C_>- f * f / *•• This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Dealerships and the Development of a Commercial District 1905-1936 Evolution of a Building Type 1905-1936 Motor Row and Chicago Architects 1905-1936 C. Form Prepared by name/title _____Linda Peters. Architectural Historian______________________ street & number 435 8. Cleveland Avenue telephone 847.506.0754 city or town ___Arlington Heights________________state IL zip code 60005 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N

Exhibit A LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N. Sheridan Rd. Final Landmark Recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, August 7, 2014 CITY OF CHICAGO Rahm Emanuel, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is re- sponsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city per- mits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recom- mendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment dur- ing the designation process. Only language contained within a designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. 2 CAIRO SUPPER CLUB BUILDING (ORIGINALLY WINSTON BUILDING) 4015-4017 N. SHERIDAN RD. BUILT: 1920 ARCHITECT: PAUL GERHARDT, SR. Located in the Uptown community area, the Cairo Supper Club Building is an unusual building de- signed in the Egyptian Revival architectural style, rarely used for Chicago buildings. This one-story commercial building is clad with multi-colored terra cotta, created by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company and ornamented with a variety of ancient Egyptian motifs, including lotus-decorated col- umns and a concave “cavetto” cornice with a winged-scarab medallion. -

Christie's to Auction Architectural Elements Of

For Immediate Release May 8, 2009 Contact: Milena Sales 212.636.2680 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S TO AUCTION ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE DANKMAR ADLER & LOUIS SULLIVAN’S CHICAGO STOCK EXCHANGE BUILDING IN EXCEPTIONAL SALE THIS JUNE 20th Century Decorative Art & Design June 2, 2009 New York – Christie’s New York’s Spring 20th Century Decorative Art & Design sale takes place June 2 and will provide an exciting array of engaging and appealing works from all the major movements of the 20th century, exemplifying the most creative and captivating designs that spanned the century. A separate release is available. A highlight of this sale is the superb group of 7 lots featuring architectural elements from Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Building. Jeni Sandberg, Christie's Specialist, 20th Century Decorative Art & Design says, “Christie’s prides itself on bringing works of historical importance and cultural relevance to the international art market. We are therefore delighted to offer these remarkable lots, which were designed by Louis Sullivan, one the great creative geniuses of American Architectural history, in our upcoming 20th Century Decorative Art and Design Sale June 2, 2009.” Louis Sullivan and the Chicago Stock Exchange Building Widely acknowledged as one of the 20th century’s most important and influential American architects, Louis Sullivan is considered by many as “the father of modern architecture.” Espousing the influential notion that “form ever follows function,’ Sullivan redefined the architectural mindset of subsequent generations. Despite this seemingly stark dictum, Sullivan is perhaps best known for his use of lush ornament. Natural forms were abstracted and multiplied into until recognizable only as swirling linear elements. -

Charles A. Purcell House (1909)

Charles A. Purcell House (1909). Arthur B. Heurtley House (1902). Designed by William Gray Purcell and George Feick for Purcell’s parents, Charles and Edna, Probably Frank Lloyd Wright’s great early masterpiece, it typifies what became known as the for which they left their large 1893 home on Forest Avenue in Oak Park (incidentally, just a Prairie Style, though in vibrant autumnal tones and stretching tiers of sparkling art glass. few doors down from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Heurtley House.) It was later elaborated upon by Wright here visits the second owners of the house, his sister Jane Porter and her husband Louis Sullivan’s chief draughtsman George Grant Elmslie, who by 1909 on the upper veranda, sometime in the early 1940s. had left Sullivan to partner with Purcell. Philander Barclay. My personal favorite of all the famous Oak Park residents, Barclay was the loner son of a Marion Street druggist, later operating his own bicycle shop around the corner on North Boulevard, in his spare time collecting photos and stories of the area, and eventually taking hundreds of his own over a period of decades—all of which are now on deposit at The Potowatami. Residing in various and disparate the Historical Society. In a 1931 Oak Leaves interview he said midwestern locales from what is now Michigan to “Nobody ever thinks about saving the past until the past is gone.” Wisconsin to Illinois, the Illinois tribe is perhaps best A morphine addict, he committed suicide in 1940 at the age of 61. known for the 1812 Battle of Fort Dearborn, suffering profoundly from the “Removal Period” which followed. -

OTHER PRAIRIE SCHOOL ARCHITECTS George Washington

OTHER PRAIRIE SCHOOL ARCHITECTS George Washington Maher (1864–1926) Maher, at the age of 18, began working for the architectural firm of Bauer & Hill in Chicago before entering Silsbee’s office with Wright and Elmslie. Between late 1889 and early 1890, Maher formed a brief partnership with Charles Corwin. He then practiced independently until his son Philip joined him in the early 1920s. Maher developed his “motif-rhythm” design theory, which involved using a decorative symbol throughout a building. In Pleasant Home, the Farson-Mills House (Oak Park, 1897), he used a lion and a circle and tray motif. Maher enjoyed considerable social success, designing many houses on Chicago’s North Shore and several buildings for Northwestern University, including the gymnasium (1908–1909) and the Swift Hall of Engineering. In Winona, Minnesota, Maher designed the J. R. Watkins Administration Building (1911 – 1913), and the Winona Savings Bank (1913). Like Wright, Maher hoped to create an American style, but as his career progressed his designs became less original and relied more on past foreign styles. Maher’s frustration with his career may have led to his suicide in 1926. Dwight Heald Perkins (1867–1941) Perkins moved to Chicago from Memphis at age 12. He worked in the Stockyards and then in the architectural firm of Wheelock & Clay. A family friend financed sending Perkins to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he studied architecture for two years and then taught for a year. He returned to Chicago in 1888 after working briefly for Henry Hobson Richardson. Between 1888 and 1894 Perkins worked for Burnham & Root. -

First Chicago School

FIRST CHICAGO SCHOOL JASON HALE, TONY EDWARDS TERRANCE GREEN ORIGINS In the 1880s Chicago created a group of architects whose work eventually had a huge effect on architecture. The early buildings of the First Chicago School like the Auditorium, “had traditional load-bearing walls” Martin Roche, William Holabird, and Louis Sullivan all played a huge role in the development of the first chicago school MATERIALS USED iron beams Steel Brick Stone Cladding CHARACTERISTICS The "Chicago window“ originated from this style of architecture They called this the commercial style because of the new tall buildings being created The windows and columns were changed to make the buildings look not as big FEATURES Steel-Frame Buildings with special cladding This material made big plate-glass window areas better and limited certain things as well The “Chicago Window” which was built using this style “combined the functions of light-gathering and natural ventilation” and create a better window DESIGN The Auditorium building was designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan The Auditorium building was a tall building with heavy outer walls, and it was similar to the appearance of the Marshall Field Warehouse One of the most greatest features of the Auditorium building was “its massive raft foundation” DANKMAR ALDER Adler served in the Union Army during the Civil War Dankmar Adler played a huge role in the rebuilding much of Chicago after the Great Chicago Fire He designed many great buildings such as skyscrapers that brought out the steel skeleton through their outter design he created WILLIAM HOLABIRD He served in the United States Military Academy then moved to chicago He worked on architecture with O. -

Woodbury County Courthouse National Register of Historic Places

Iowa Woodbury DEC 18 1973 Woodbury County Courthouse Seventh and Douglas Sioux City Sixth Iowa 14 Woodbury 193 County Jail County of Woodbury Sioux City Iowa 14 Housed in the Courthouse Seventh and Douglas Sioux City Iowa 14 The Woodbury County Courthouse, designed in the Prairie School style, is a large brick and granite structure of two parts—a rectangular block and eight story shaft or tower. Reminiscent of Louis Sullivan's work, the exterior presents a strong geometric profile, its surface alive with the contrast of Roman brick bands and terracotta geometric- organic detail. Primary colors are introduced by leaded glass win- dows, the polychromatic terracotta modeling and mosaic designs. Bronze doors open to the interior where rooms are distributed around the central rotunda area which culminates in a glass dome. Floors are quartzite tile, the walls Roman brick and terracotta. Mural paintings cover large areas of wall plaster between square brick piers heavily laden with the terracotta ornament. The first floor offices are irregular in size to accomodate their various uses. The four major courtrooms on the second floor are placed symmetrically around the rotunda area and joined by groups of offices and jury chambers. The remaining floors of the tower contain more offices and meeting halls, and an art gallery. No major alterations have been made on the exterior or interior, but some having to do with plumbing, electrical wiring and the windows are contemplated. The foundation and masonry show no cracks. 1918 The Woodbury County Courthouse completed in 1918, is considered to be the only public building in the Prairie School Style designed by the Chicago firm of Purcell and Elmslie. -

Office Buildings of the Chicago School: the Restoration of the Reliance Building

Stephen J. Kelley Office Buildings of the Chicago School: The Restoration of the Reliance Building The American Architectural Hislorian Carl Condit wrote of exterior enclosure. These supporting brackets will be so ihe Reliance Building, "If any work of the structural arl in arranged as to permit an independent removal of any pari the nineteenth Century anticipated the future, it is this one. of the exterior lining, which may have been damaged by The building is the Iriumph of the structuralist and funclion- fire or otherwise."2 alist approach of the Chicago School. In its grace and air- Chicago architect William LeBaron Jenney is widely rec- iness, in the purity and exactitude of its proportions and ognized as the innovator of the application of the iron details, in the brilliant perfection of ils transparent eleva- frame and masonry curtain wall for skyscraper construc- tions, it Stands loday as an exciting exhibition of the poten- tion. The Home Insurance Building, completed in 1885, lial kinesthetic expressiveness of the structural art."' The exhibited the essentials of the fully-developed skyscraper Reliance Building remains today as the "swan song" of the on its main facades with a masonry curtain wall.' Span• Chicago School. This building, well known throughout the drei beams supported the exterior walls at the fourth, sixth, world and lisled on the US National Register of Historie ninth, and above the tenth levels. These loads were Irans- Places, is presenlly being restored. Phase I of this process ferred to stone pier footings via the metal frame wilhout which addresses the exterior building envelope was com- load-bearing masonry walls.'1 The strueture however had pleted in November of 1995.