The Dead Tagged with Birmingham,Regeneration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016 / 17

Annual Report 2016 / 17 BMT_Annual Report 16/17.indd 1 03/11/2017 10:39 Reflecting Birmingham to the World, & the World to Birmingham Registered Charity Number: 1147014 Cover image © 2016 Christie’s Images Limited. Image p.24 © Vanley Burke. BMT_Annual Report 16/17.indd 2 03/11/2017 10:39 02 – 03 Birmingham Museums Trust is an independent CONTENTS educational charity formed in 2012. 04 CHAIR’S FOREWORD It cares for Birmingham’s internationally important collection of over 800,000 objects 05 DIRECTOR’S INTRODUCTION which are stored and displayed in nine unique venues including six Listed Buildings and one 06 OUR ACHIEVEMENTS Scheduled Ancient Monument. 08 AUDIENCES Birmingham Museums Trust is a company limited by guarantee. 12 SUPPORTERS 14 VENUES 15 Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery 16 Aston Hall 17 Blakesley Hall 18 Museum of the Jewellery Quarter 19 Sarehole Mill 20 Soho House 21 Thinktank Science Museum 22 Museum Collection Centre 23 Weoley Castle 24 COLLECTIONS 26 CURATORIAL 28 MAKING IT HAPPEN 30 TRADING 31 DEVELOPMENT 32 FINANCES 35 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 36 TALKS AND LECTURES BMT_Annual Report 16/17.indd 3 03/11/2017 10:39 Chair’s foreword Visitor numbers exceeded one million for the It is with pleasure that third year running, and younger and more diverse audiences visited our nine museums. Birmingham I present the 2016/17 Museum & Art Gallery was the 88th most visited art museum in the world. We won seven awards annual report for and attracted more school children to our venues Birmingham Museums than we have for five years. A Wellcome Trust funded outreach project enabled Trust. -

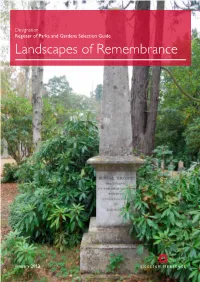

Designation Selection Guide: Landscapes of Remembrance

Designation Register of Parks and Gardens Selection Guide Landscapes of Remembrance January 2013 INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITIONS REGISTER OF PARKS AND GARDENS The Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic SELECTION GUIDE: LANDSCAPES Interest in England was set up in 1983. It identifies designed OF REMEMBRANCE landscapes of many types, private and public, which are identified using explicit criteria to possess special interest. To date (2012) approximately1, 620 sites have been included Contents on the Register. In this way English Heritage seeks to increase awareness of their historic interest, and to encourage appropriate long-term management. Although registration is a statutory INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITIONS ....................2 designation, there are no specific statutory controls for registered parks and gardens, unlike listed buildings or scheduled monuments. HISTORICAL SUMMARY ..............................................2 However, the Government’s National Planning Policy Framework (http://www.communities.gov.uk/publications/planningandbuilding/ Churchyards .......................................................................... 2 nppf) gives registered parks and gardens an equal status in the planning system with listed buildings and scheduled monuments Denominational burial grounds ........................................ 3 (see especially paragraph 132). Cemeteries ............................................................................ 3 This is one of four complementary selection guides which briefly Crematoria -

APPENDIX 2 Full Business Case (FBC) 1. General Information

APPENDIX 2 Full Business Case (FBC) 1. General Information Directorate Economy Portfolio/Committee Leader’s Portfolio Project Title Jewellery Project Code Revenue TA- Quarter 01843-01 Cemeteries Capital – to follow Project Description Aims and Objectives The project aims to reinstate, restore and improve the damaged and vulnerable fabric of Birmingham’s historic Jewellery Quarter cemeteries – Key Hill and Warstone Lane – and make that heritage more accessible to a wider range of people. Their importance is recognised in the Grade II* status of Key Hill Cemetery in the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, and the Grade II status of Warstone Lane Cemetery. The project is an integral part of the wider heritage of the Jewellery Quarter and complements the other heritage investment taking place here, such as the JQ Townscape Heritage programme and the completion of the Coffin Works (both part-funded by HLF). Heritage is a key part of the Jewellery Quarter with over 200 listed buildings and four other museums (Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Pen Room, Coffin Works, JW Evans). The funding provides an opportunity to bring much needed investment to conserve and enhance two important listed cemeteries, providing a resource and opportunities for visitors and residents alike to visit, enjoy and get involved with. The project will deliver the following (full details are set out in the Design Specification): Full 10-year management and maintenance plans for both cemeteries Interpretation plan Capital works - Warstone Lane cemetery Reinstatement of the historical boundary railings (removed in the 1950s), stone piers and entrance gates on all road frontages; Resurfacing pathways to improve access; Renovation of the catacomb stonework and installation of a safety balustrade; Creation of a new Garden of Memory and Reflection in the form of a paved seating area reinterpreting the footprint of the former (now demolished) chapel; General tree and vegetation management. -

Statistical Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Acid Deposition in the West Midlands, England, United Kingdom

Statistical Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Acid Deposition in the West Midlands, England, United Kingdom A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Avery Rose Cota-Guertin IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Dr. Howard Mooers January 2012 © Avery Rose Cota-Guertin 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to take this time to thank those people who played a crucial part in the completion of this thesis. I would like to thank my mother, Roxanne, and father, Jim. Without their unconditional love and support I would not be where I am today. I would also like to thank my husband, Greg, for his continued and everlasting support. With this I owe them all greatly for being my rock through this entire process. I would like to thank my thesis committee members for their guidance and support throughout this journey. First and foremost, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Howard Mooers, for the advisement and mentoring necessary for a successful completion. Secondly, I would like to extend great thanks to Dr. Ron Regal for patiently mentoring me through the rollercoaster ride of Statistical Analysis Software (SAS). Without his assistance in learning SAS techniques and procedures I would still be drowning in a sea of coding procedures. And thank you to Dr. Erik Brown for taking the time to serve on my thesis committee for the past two years. For taking the time out of his busy schedule to meet with Howard and me during our trip to England, I owe a great thanks to Dr. -

Restoring the Chamberlains' Highbury

Restoring The Chamberlains’ Highbury Contents Foreword 5 Restoring The Chamberlains’ Highbury 6-9 The Highbury Restoration Project 10-13 Historic Timelime 14-15 The Chamberlains 16-17 The Future 20-21 Further reading & Acknowledgements 22 Restoring The Chamberlains’ Highbury 3 Foreword Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914), businessman, social reformer and controversial politician and imperialist, had an early involvement in civic leadership. He was elected mayor of Birmingham in 1873. His pioneering efforts in educational reform, slum clearance, improved housing, and municipalisation of public utilities led to Birmingham being described as the ‘best governed city in the world’ (The Harpers Monthly 1890). The house called ‘Highbury’ and its surrounding 30 acre estate form one of Birmingham’s most important heritage sites. Commissioned by Joseph Chamberlain and completed in 1880, the Grade II* listed house was Les Sparks OBE designed by the prominent Birmingham architect J. H. Chamberlain. Chair, Chamberlain Highbury Trust The grounds are listed Grade II on Historic England’s Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest. The Chamberlain legacy is still the subject of debate and rightly so. Joe Chamberlain, as Churchill commented, ‘made the weather’ politically and was both adored and hated. The Commonwealth and the rich ethnic and cultural diversity we celebrate in today’s Birmingham, is distant from his time yet connected, for good or ill, to decisions made by ‘Brummagem Joe’. If modern Birmingham is to continue to grow and prosper, then the development of purposeful and ethical leadership models will be central to the stewardship of its public and private institutions and the promotion of successful entrepreneurship across its diverse population. -

JEWELLERY Quarter Festival Guide 2019

JEWELLERY QuARTER FESTIvAL GuIDE 2019 PICK ME uP I'M FREE th th SAT 29 & SuN 30 June Experience the energy & heritage of Birmingham’s historic Quarter Brought to you by the JQBID JQBID CELEBRATE WITH uS Welcome to the JQ Festival The Jam House It’s a Happy 20th Birthday to the Jam House TH TH who are celebrating with a special outdoor 29 & 30 June event within the picturesque St Paul’s Square with a whole host of bands playing live music. Sat 29th June | 1pm - 7pm | FREE For the fifth year in a row the Jewellery Quarter Festival returns to celebrate the energy and heritage of the Quarter! With free entertainment, tours, events and music this is James Watt Bicentennary the perfect opportunity to come and explore Paying homage to the bicentenary of the death this unique Birmingham neighbourhood. of James Watt, there’ll be plenty of activities throughout the day celebrating this anniversary. The JQ Festival is organised by the Jewellery Denver Light Railway will be bringing a Quarter Business Improvement District and rideable steam engine to the JQ and a James is funded by the local businesses. Watt reenactor will be roaming at the Festival. FREE! Get exclusive offers in the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon-landing Taking us from the 19th century to the 20th we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Jewellery Quarter Apollo 11 Moon-landing together with Thinktank, Birmingham Museums Trust and CircusMash who will be bringing their ‘out of this world’ performance. Don’t forget to pick up your copy of the JQ Voucher Booklet for exclusive discounts and offers throughout LITTLE BooK oF vouCHERS Summer 2019! If you would like a booklet, grab one from a local JQ café or contact the JQBID team Packed full of special offers and Page 18 - 27 exclusive discounts from ([email protected]). -

Discover & Explore

Discover & Explore Birmingham Museums WHAT’S ON IN 2018 BIRMINGHAM MUSEUM & ART GALLERY / ASTON HALL THINKTANK SCIENCE MUSEUM / BLAKESLEY HALL / SOHO HOUSE SAREHOLE MILL / MUSEUM OF THE JEWELLERY QUARTER MUSEUM COLLECTION CENTRE / WEOLEY CASTLE birminghammuseums.org.uk FANTASTIC FREE DAYS OUT WITH Welcome to Birmingham Museums Birmingham Birmingham has one of the best civic museum collections of any city in England, Museums all housed in nine wonderful locations. From Anglo-Saxon gold, a magnificent Jacobean mansion to a perfectly preserved jewellery factory, Membership Birmingham Museums offer truly inspirational days out. BIRMINGHAM MUSEUM p4 THINKTANK p8 ASTON HALL p10 • FREE entry to Thinktank, Birmingham Science & ART GALLERY SCIENCE MUSEUM Museum and SEVEN heritage sites (Thinktank entry included in Membership Plus only) • FREE guided tours at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery and the heritage sites • FREE arts and crafts activities • 10% off in our cafés and shops MUSEUM OF THE JEWELLERY QUARTER p11 BLAKESLEY HALL p12 SAREHOLE MILL p13 • Regular e-news MUSEUM COLLECTION SOHO HOUSE p14 WEOLEY CASTLE p15 CENTRE p15 Support Us Birmingham Museums is a charity. We are responsible for generating the income to run our unique museum sites, welcome 1 million visitors each Terms and Conditions apply. year and care for over 800,000 priceless objects on behalf of the people See birminghammuseums.org.uk for full terms. of Birmingham. You can help us by making a donation at one of our sites, online or by post. Text to donate: text ‘BMUS01 £3’ to 70070 Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery first opened in 1885 and is housed in a Grade II* listed city centre landmark building. -

Bifhs-Usa Journal

BIFHS-USA JOURNAL VOLUME XXV, NUMBER 1 Spring/Summer 2014 JOURNAL OF THE BRITISH ISLES FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY- U.S.A. BRITISH ISLES FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY- U.S.A. Board of Directors President Linda Jonas [email protected] 1st Vice President, Programs Open 2nd Vice President, Membership Dolores Andersen [email protected] Recording Secretary Open Treasurer (interim) Lydia Davis Jeffrey [email protected] Corresponding Secretary Terry Brown [email protected] Newsletter Editor Fran Smith [email protected] Journal Editor Barbara Randall [email protected] Past President Lydia Davis Jeffrey [email protected] Members at Large Sue Kaplan Linkedin.com/in/suekaplanmba/ Miriam Fitch Gerrianne Williams Nancy Ellen Carlberg [email protected] 714- 772- 2849 Mailing address: BIFHS-USA Website: www.bifhsusa.org 9854 National Blvd., #304 www.facebook.com/bifhsusa Los Angeles, CA 90034-2713 USA BIFHS-USA Journal Volume XXV, Number 1 President’s Message… Dear BIFHS-USA members, Welcome to the new PDF version of the Journal! The benefits of PDF as opposed to the old paper version are many. First, we are now able to show color images. You will see many of these in this issue. Next, you will be able to save your Journal to your computer, then read and review articles anywhere. The articles are also searchable, so you will no longer have to struggle to find information. If any article contains a website link, you will be able to click the link directly from the Journal and go right to the website. For more great news, the Society now has a Facebook page. -

Sprint Network Plan Wolverhampton a Park and Zoo 3 Science Park 5 1 4 Royal Air Force 6 4 a Museum A

9 4 TAMWORTH 4 A 0 6 Drayton Manor 4 Sprint Network Plan Wolverhampton A Park and Zoo 3 Science park 5 1 4 Royal Air Force 6 4 A Museum A M6 M42/M1 University of The Royal Walsall East Midlands & City of Wolverhampton Wolverhampton & Wales College Wolverhampton NHS Trust College 10 A454 WOLVERHAMPTON WALSALL Good Hope 9 Hospital 4 Sutton T3 4 9 A Park 463 M6 A (T M WEDNESBURY M ol D 6 l) LA N SUTTON D A M 4 E 1 2 TR O 1 COLDF ELD 4 04 M 8 7 A4 8 8 3 A A 4 1 2 A 3 8 45 Alexander 2 8 WEST StadiuAm 14 3 4 4 Sandwell Pype B BROMW CH & West Hayes Park 9 Birmingham 61 M ERD NGTON 4 Hospitals 6 A PERRY Sandwell Games Living Museum BARR College Village Spaghetti DUDLEY Dudley Junction College 1 6 Centre West Bromwich Aston A38 Dudley Albion FC Villa FC 5 Castle Dudley & Walsall M D 5 LAN & Zoo Mental Health M D M ET A41 Star City RO Aston Hall Aston M 4 University 2 2 B RM NGHAM Park C TY CENTRE Snow Hill 7a for HS2 7 3a A Edgbaston Birmingham 4 4 BEARWOOD 9 City FC Hospital 1 1 6 A Birmingham 4 456 M6 A New Street Moor Street Business Park Birmingham City University Sheldon M6/M1 Birmingham A Birmingham Birmingham 45 London & Botanical Gardens Environmental Interchange The South East Enterprise District Queen for HS2 HALESOWEN Elizabeth Edgbaston A41 Hospital Stadium 3 Woodgate Valley World 6 1 4 STOURBR DGE 4 Jaguar A Land Rover National A456 The University Birmingham Motorcycle KEY of Birmingham HALL GREEN International Museum Senneleys Life Science 8 Campus Kings Park 3 A34 Birmingham through Sandwell to Walsall A Heath 5 Newman Park A M University World 4 3 A Birmingham to Sutton Coalfield via Langley 5 3 4 SOL HULL NORTHF ELD Solihull A45 Birmingham to Birmingham Airport serving NEC Touchwood LONGBR DGE College Solihull 5 College Bournville A College 4 2 5 4 2 Longbridge M Technology Park 4 M5 Cofton Park The South West Blythe Valley 4 Business Park & South Wales Lickey Hills The Victoria Works Heritage Motor Centre. -

Birmingham 2018

Auf den Spuren J.R.R. Tolkiens Schlemmen im Balti Triangle Farbenpracht in der Kathedrale Junge Kunst im Szeneviertel Digbeth inklusive WEB Anna Regeniter APP City|Trip EXTRATIPPS Z Hier war schon Königin Victoria zu Gast: übernachten im The Old Crown, Birminghams ältestem Pub S. 128 Z Sonntagsbraten direkt am Bootsanleger: im Gastropub The Canal House S. 73 Birmingham Z Den einen Ring finden: Schmuckshopping im Jewellery Quarter S. 88 mit großem Z Auge in Auge mit Rochen und Haien: City-Faltplan das National Sea Life Centre S. 29 Z Hier wurde die Industrielle Revolution eingeleitet: eine Führung durch das Soho House S. 49 Z Tee- und Kaffeegenuss bei sanftem Wellengang: das Hausbootcafé The Floating Coffee Co. S. 76 Z Zischend und dampfend nach Stratford-upon-Avon: eine Reise mit dem Shakespeare Express S. 58 Z Gruselige Gewölbe und Spukgeschichten: unterwegs auf dem Warstone Lane Cemetery S. 37 Z Mit Rittern und Rössern in den Rosenkrieg: im Warwick Castle wird das Mittelalter zum Leben erweckt S. 59 Z Ruhe jetzt, sonst gibt es Nachsitzen: eine Schulstunde im Black Country Living Museum S. 63 P Erlebnis vor- j Die Library of Birmingham schläge für einen ist ein Palast für Bücher (S. 22) Kurztrip, Seite 10 Viele EXTRATIPPS: Entdecken ++ Genießen ++ Shopping ++ Wohlfühlen ++ Staunen ++ Vergnügen ++ Anna Regeniter CITY|TRIP BIRMINGHAM Nicht verpassen! Karte S. 3 Birmingham Cathedral [D3] Museum of the É Die Kirche St Philip mag eine der Ú Jewellery Quarter [B1] kleinsten Kathedralen Englands sein, aber Bei den informativen und amüsanten sie besticht durch die herrlichen Buntglas Führungen durch die ehemalige Schmuck fenster des Künstlers Edward BurneJones fabrik lernt man viel über die Schmuck (s. -

Birmingham Jewellery Quarter Heritage Trail

BIRMINGHAM JEWELLERY QUARTER HERITAGE TRAIL 11 BROUGHT TO YOU BY BIRMINGHAM JEWELLERY QUARTER HERITAGE TRAIL Birmingham’s famous Jewellery Quarter is completely unique - there is no other historic townscape like it in the world. It is an area rich in heritage, but what makes it so special is that it is still also a living, working community. The purpose of this walking trail is to provide an introduction to the Quarter’s past and present, and to encourage visitors to discover more about this fascinating area. This trail is printed and distributed by the Jewellery Quarter Development Trust (JQDT). The development of the Jewellery Quarter. Goldsmiths and silversmiths have been working in what we now call the Jewellery Quarter for more than 200 years. Originally scattered across Birmingham, they began to congregate in the Hockley area from 1760 onwards. The main reason for this was the development of the Colmore family’s Newhall estate which released more land for housing and manufacturing. 1 Precious metal working grew out of the ‘toy’ trades – not children’s playthings but buckles, buttons and other small metal trinkets. ‘Brummagem toys’ were produced in their hundreds and thousands, in cut-steel, brass and silver. Westley’s Map of Birmingham, 1731 - Confusingly north is to the right! As the trade expanded new streets were laid out across former rural estates, and substantial new houses were built for wealthy manufacturers. Alongside these large houses, terraces of artisans’ homes were also constructed. In time the gardens of these houses became built up with workshops and spare rooms had work benches installed. -

Birmingham Museums Birmingham Has One of the Best Civic Museum Collections of Any City in England, All Housed in Nine Wonderful Locations

CONTENTS * 4 - 63 EVERY BIRMINGHAM FESTIVAL in 2020 6 OF THE BEST PLACES YOU MIGHT WANT TO CHECK OUT IN BIRMINGHAM 6 PARKS & WALKS 14 BARS 24 PLACES TO EAT PART ONE 36 MUSIC VENUES 46 MUSEUMS 50 PLACES TO EAT PART TWO 64 INDEX BY CATEGORY 68 CREDITS * IT IS JUST POSSIBLE THAT WE'VE MISSED ONE OR TWO. SEE BIRMINGHAMFESTIVALS.COM FOR UPDATES. II 1 WELCOMEWELCOME “Life is a festival only to the wise” - Ralph Waldo Emerson 2 3 Chinese New Year First Bite & Bite Size JANUARY 18 bit.ly/1stBite2020 MAC Birmingham & Warwick Arts Centre Bite Size and its sister festival First Bite exist to develop and showcase new work from the Midlands. The activity runs across four public events and includes a fully supported commissioning process for three regional theatre makers. Ideas of Noise JANUARY 23 – FEBRUARY 9 bit.ly/IDNoise2020 Birmingham, Stourbridge and Coventry Arts and Science Festival Contemporary classical performance rubs shoulders with electronica, visual art and University of Birmingham Arts & film. This edition of Ideas of Noise spreads Science Festival its programme of cutting edge music, art JAN 2020 - MAY 2020 and interactive events across Birmingham, bit.ly/ArtsnScience2020 Stourbridge and Coventry. JANUARY Various venues across Birmingham Birmingham University’s annual Chinese New Year celebration of research, culture and JANUARY 24–26 collaboration - on and beyond its bit.ly/YearoftheRat2020 Edgbaston campus - is currently Southside, Birmingham showcasing the launch of the University’s Welcome in the Year of the Rat at new Green Heart parkland. Its spring Birmingham’s annual Chinatown gathering, programme sees thinkers, makers and the UK’s largest celebration of the lunar doers engage with the theme ‘Hope’.