Draft. Please Do Not Circulate Without Author's Permission. 1 Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change Or None of the Above??

IUSB Graduate Journal Ill 1 Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change or None of the Above?? by:jacqueline Becker Department of English ABSTRACT: This paper explores the many different ways in which Communism is portrayed within Richard Wright's novel Native Son. It also seeks to illustrate that regardless of the reasoning behind the conflicted portrayal of Communism, within the text, it does serve a vital purpose, and that is to illustrate to the reader that there is no easy answer or solution for the problems facing society. Bigger and his actions cannot be simply dismissed as a product of a damaged society, nor can Communism be seen as an all-encompassing saving grace that will fix all of societies woes. Instead, this novel, seeks to illustrate the type of people that can be produced in a society divided by racial class lines. It shows what can happen when one oppressed group feels as though they have no power over their own lives. I have attempted to illustrate that what Wright ultimately achieved, through his novel Native Son, is to illuminate to readers of the time that a serious problem existed within their society, specifically in Chicago within the "Black Belt" and that the solution lies not with one social group or political party, not through senseless violence, but rather through changes in policy. ~Research~ 2 lll Jacqueline Becker Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change or None of the Above?? ichard Wright's novel, Native Son, presents Communism in many different lights. On the one hand, the pushy nature R of Jan and Mary, two white characters trying to share their beliefs about an equal society under Communism, by forcing Bigger, the black protagonist, to dine and drink with them, is ultimately what leads to Mary's death. -

How Bigger Was Born Anew

Fall 2020 29 ow Bier as Born new datation Reuration and Double Consciousness in Nambi E elle’s Native Son Isaiah Matthew Wooden This essay analyzes Nambi E. Kelley’s stage adaptation of Native Son to consider the ways tt Aicn Aeicn is itlie by n constitte to cts o etion t sharpens particular focus on how Kelley reinvigorates Wright’s novel’s searing social and cil cities by ctiely ein te oisin etpo o oble consciosness n iin ne o, enin, n se to te etpo, elleys Native Son extends the debates about “the problem of the color line” that Du Bois’s writing helped engender at te beinnin o te tentiet centy into te tentyst n, in so oin, opens citicl space to reckon with the persistent and pernicious problem of anti-Black racism. ewords adaptation, refguration, double consciousness, Native Son, Nambi E. Kelley This essay takes as a central point of departure the claim that African American drama is vitalized by and, indeed, constituted through acts of refguration. It is such acts that endow the remarkably capacious genre with any sense or semblance of coherence. Retion is notably a word with multiple signifcations. It calls to mind processes of representation and recalculation. It also points to matters of meaning-making and modifcation. The pref re does important work here, suggesting change, alteration, or even improvement. For the purposes of this essay, I use etion to refer to the strategies, practices, methods, and techniques that African American dramatists deploy to transform or give new meaning to certain ideas, concepts, artifacts, and histories, thereby opening up fresh interpretive and defnitional possibilities and, when appropriate, prompting much-needed reckonings. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities H. Alexander Nejako College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nejako, H. Alexander, "Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625892. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nehz-v842 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD WRIGHT AND RALPH ELLISON: CONFLICTING MASCULINITIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by H. Alexander Nejako 1994 ProQuest Number: 10629319 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10629319 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Materiality and Masculinity in African American Literature. (2014) Directed by Dr

GIBSON, SCOTT THOMAS, Ph.D. Heavy Things: Materiality and Masculinity in African American Literature. (2014) Directed by Dr. SallyAnn H. Ferguson. 222 pp. Heavy Things illustrates how African American writers redefine black manhood through metaphors of heaviness, figured primarily through their representation of material objects. Taking the literal and figurative weight the narrator’s briefcase in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man as a starting point, this dissertation examines literary representations of material objects, including gifts, toys, keepsakes, historical documents, statues, and souvenirs as modes of critiquing the materialist foundations of manhood in the United States. Historically, materialism has facilitated white male domination over black men by associating property ownership with both whiteness and manhood. These writers not only reject materialism as a vehicle of oppression but also reveal alternative paths along which black men can thrive in a hostile American society. Each chapter of my analysis is structured around specific kinds of “heavy” objects—gifts, artifacts, and memorials—that liberate black men from white definitions of manhood based in possessive materialism. In Frederick Douglass’s Narrative and Ernest Gaines’s A Lesson Before Dying, gifts reestablished ties between alienated black men and their communities. In Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon and John Edgar Wideman’s Fatheralong, black sons attempt to reconcile their fraught relationships with their fathers through the recovery of historical artifacts. In Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days and Emily Raboteau’s The Professor’s Daughter, black men and women use commemorative objects such as monuments and memorials to reimagine black male abjection as a trope of healing. -

Native Son (Questions)

Native Son (Questions) 1 Wright writes of Bigger Thomas: “these were the rhythms of his life; indifference and violence; periods of abstract brooding and periods of intense desire; moments of silence and moments of anger” … Does Wright intend us to relate to Bigger as a human being – or has he deliberately made him an embodiment of oppressive social and political forces? Is there anything admirable about Bigger? Does he change by the end of the book? 2 James Baldwin, an early protégé of Wright’s, later attacked the older writer for his self-righteousness and reliance on stereo-types… In his famous essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel” Baldwin compared Bigger to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom, and dismissed Native Son as “protest” fiction. Do you agree? 3 When Bigger stands confronted by his family in jail, he thinks… they ought to be glad he was a murderer; “had he not taken on himself the crime of being black?” Talk about Bigger as a victim and sacrificial figure. If Wright wanted us to pity Bigger, why did he portray him as so brutal? 4 How dated does this book seem in its depiction of racial hatred and guilt? Have we as a society moved beyond the rage and hostility that Wright depicts between blacks and whites? Or are we still living in a culture that could produce a figure like Bigger Thomas? https://www.litlovers.com/reading-guides/fiction/719-native-son-wright?start=3 Native Son (About the Author) Author: Richard Wright Born: September 4, 1908 Where: near Natchez, MS Education: Smith-Robertson Junior High, Jackson MS Died: November 28, 1960 Where: Paris, France Richard Wright was the first 20th century African-American writer to command both critical acclaim and popular success. -

Paul Green Foundation

Paul Green Foundation NEWS – October 2017 Native Son’s New Adaptation PAUL GREEN ANNUAL MEETING Playwright Nambi Kelley NOVEMBER 4, 2017 has written plays for NC BOTANICAL GARDEN Steppenwolf, Goodman Theatre and Lincoln Center CHAPEL HILL, NC and most recently was named playwright-in-residence at The 2017 the National Black Theatre in New York. Kelley’s adaptation of Native Son was National Theatre Conference presented to critical acclaim for the premiere December 1-3 in New York City production at the Court Theatre/American Blues Each year the National Theatre Conference Festival. Since that first production it has been Person of the Year names the Paul Green produced in New York, California, Georgia and Award winner. This year’s Person of the Year – Arizona, and published by Samuel French in 2016. Molly Smith selected June Schreiner, a highly The Green Foundation joined with the Wright acclaimed young actor. Since 1989, the Paul Estate to sanction these productions. Green Foundation has honored a “young theatre professional” with this Paul Green Award. A bit of history: Paul Green and Richard Wright’s Native Son that opened on March 24, Founded in 1925, the National Theatre 1941, at the St. James Theatre in New York City, Conference is a not-for-profit organization made was produced by Orson Welles and John up of distinguished members of the American Houseman. Of the very serious disagreement that Theatre Community; Green was instrumental in ensued between Green and Wright, Dr. Laurence the founding the organization and served as Avery, Professor Emeritus, UNC-Chapel Hill president in the early years. -

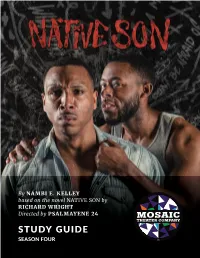

STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction

By NAMBI E. KELLEY based on the novel NATIVE SON by RICHARD WRIGHT Directed by PSALMAYENE 24 STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction “Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it.”—Augusto Boal The purpose and goal of Mosaic’s education department is simple. Our program aims to further and cultivate students’ knowledge and passion for theatre and theatre education. We strive for complete and exciting arts engagement for educators, artists, our community, and all learners in the classroom. Mosaic’s education program yearns to be a conduit for open discussion and connection to help students understand how theatre can make a profound impact in their lives, in society, and in their communities. Mosaic Theater Company of DC is thrilled to have your interest and support! Catherine Chmura Arts Education Apprentice—Mosaic Theater Company of DC Written by Catherine Chmura, Khalid Y. Long, and Isaiah M. Wooden 2 NATIVE SON MOSAIC THEATER COMPANY of DC PRESENTS NATIVE SON By Nambi E. Kelley based on the novel NATIVE SON by Richard Wright Directed by Psalmayene 24 Set Designer: Ethan Sinnott Lighting Designer: William K. D’Eugenio Costume Designer: Katie Touart Projections Designer: Dylan Uremovich Sound Designer: Nick Hernandez Properties Designer: Willow Watson Movement Specialist: Tony Thomas* Production Stage Manager: Simone Baskerville* Dramaturg: Isaiah M. Wooden & Khalid Yaya Long Table of Contents Curriculum Connections: DC Public -

Richard Wright and His Anxious Influence: on Ellison and Baldwin

Richard Wright and his Anxious Influence: On Ellison and Baldwin And in this lies Wright's most important achievement: he has converted the American Negro impulse toward self-annihilation and "going underground" into a will to confront the world, to evaluate his experience honestly, and throw his findings unashamedly into the guilty conscience of America. – Ralph Ellison, “Richard Wright’s Blues” In Uncle Tom’s Children, in Native Son, and, above all, in Black Boy, I found expressed for the first time in my life, the sorrow, the rage, and the murderous bitterness which was eating up my life and the lives of those around me. His work was an immense liberation and revelation for me. He became my ally and my witness, and alas! my father. – James Baldwin, “Alas, Poor Richard” It is not easy being a father. Sigmund Freud was right, no matter how bizarre his evidential sources: the children will come for you. To be a father is to have children, to have them under your gaze, but also to set them freer than you may have ever intended. Fatherly authority is defined, in many ways, by the insistence of his subjects on the rights of refusal, contestation, and overcoming. That is what it means to have children. They are yours, if you are the father. They inherit you. But they also belong to themselves. And that belonging-to-self thing is largely generated by struggle, opposition, and overcoming. Parricide. Richard Wright is in this way very much the father of two of the most important African- American writers writing in his shadow: James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison. -

Native Son Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Vocal and Physical Endurance that Lasts till the End.” Engaging Your Training in Native Son A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Theatre and Dance (Acting) by Terrance White Committee in charge: Marc Barricelli, Chair Eva Barnes Charles Oates Manuel Rotenberg 2017 © Terrance White, 2017 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Terrance White is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION Dedicated to Zara Laniece Mitchell my beautiful niece. Any dreams you have in this world you chase them and uncle will be right there with you to support your entire journey. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................................................................................................ iii Dedication....................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents............................................................................................................ v List of Supplemental Files.............................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements........................................................................................................ vii Abstract of the Thesis....................................................................................................