A GUIDE to FORMATTING WRITTEN WORK at SVDP St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to Proclaim MEMORIALIZING June 5

Assembly Resolution No. 347 BY: M. of A. Solages MEMORIALIZING Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to proclaim June 5, 2021, as Belmont Stakes Day in the State of New York, and commending the New York Racing Association upon the occasion of the 152nd running of the Belmont Stakes WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is one of the most important sporting events in New York State; it is the conclusion of thoroughbred racing's prestigious three-contest Triple Crown; and WHEREAS, Preceded by the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, the Belmont Stakes is nicknamed the "Test of the Champion" due to its grueling mile and a half distance; and WHEREAS, The Triple Crown has only been completed 12 times; the 12 horses to accomplish this historic feat are: Sir Barton, 1919; Gallant Fox, 1930; Omaha, 1935; War Admiral, 1937; Whirlaway, 1941; Count Fleet, 1943; Assault, 1946; Citation, 1948; Secretariat, 1973; Seattle Slew, 1977; Affirmed, 1978; and American Pharoah, 2015; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes has drawn some of the largest sporting event crowds in New York history, including 120,139 people for the 2004 running of the race; and WHEREAS, This historic event draws tens of thousands of horse racing fans annually to Belmont Park and generates millions of dollars for New York State's economy; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is shown to a national television audience of millions of people on network television; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is named after August Belmont I, a financier who made a fortune in banking in the middle to late 1800s; he also branched out -

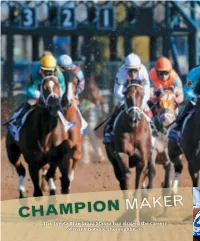

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

A Theological Reading of the Gideon-Abimelech Narrative

YAHWEH vERsus BAALISM A THEOLOGICAL READING OF THE GIDEON-ABIMELECH NARRATIVE WOLFGANG BLUEDORN A thesis submitted to Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts & Humanities April 1999 ABSTRACT This study attemptsto describethe contribution of the Abimelech narrative for the theologyof Judges.It is claimedthat the Gideonnarrative and the Abimelechnarrative need to be viewed as one narrative that focuseson the demonstrationof YHWH'S superiority over Baalism, and that the deliverance from the Midianites in the Gideon narrative, Abimelech's kingship, and the theme of retribution in the Abimelech narrative serve as the tangible matter by which the abstracttheological theme becomesnarratable. The introduction to the Gideon narrative, which focuses on Israel's idolatry in a previously unparalleled way in Judges,anticipates a theological narrative to demonstrate that YHWH is god. YHwH's prophet defines the general theological background and theme for the narrative by accusing Israel of having abandonedYHwH despite his deeds in their history and having worshipped foreign gods instead. YHWH calls Gideon to demolish the idolatrous objects of Baalism in response, so that Baalism becomes an example of any idolatrous cult. Joash as the representativeof Baalism specifies the defined theme by proposing that whichever god demonstrateshis divine power shall be recognised as god. The following episodesof the battle against the Midianites contrast Gideon's inadequateresources with his selfish attempt to be honoured for the victory, assignthe victory to YHWH,who remains in control and who thus demonstrateshis divine power, and show that Baal is not presentin the narrative. -

Preakness Stakes .Fifty-Three Fillies Have Competed in the Preakness with Start in 1873: Rfive Crossing the Line First The

THE PREAKNESS Table of Contents (Preakness Section) History . .P-3 All-Time Starters . P-31. Owners . P-41 Trainers . P-45 Jockeys . P-55 Preakness Charts . P-63. Triple Crown . P-91. PREAKNESS HISTORY PREAKNESS FACTS & FIGURES RIDING & SADDLING: WOMEN & THE MIDDLE JEWEL: wo people have ridden and sad- dled Preakness winners . Louis J . RIDERS: Schaefer won the 1929 Preakness Patricia Cooksey 1985 Tajawa 6th T Andrea Seefeldt 1994 Looming 7th aboard Dr . Freeland and in 1939, ten years later saddled Challedon to victory . Rosie Napravnik 2013 Mylute 3rd John Longden duplicated the feat, win- TRAINERS: ning the 1943 Preakness astride Count Judy Johnson 1968 Sir Beau 7th Fleet and saddling Majestic Prince, the Judith Zouck 1980 Samoyed 6th victor in 1969 . Nancy Heil 1990 Fighting Notion 5th Shelly Riley 1992 Casual Lies 3rd AFRICAN-AMERICAN Dean Gaudet 1992 Speakerphone 14th RIDERS: Penny Lewis 1993 Hegar 9th Cynthia Reese 1996 In Contention 6th even African-American riders have Jean Rofe 1998 Silver’s Prospect 10th had Preakness mounts, including Jennifer Pederson 2001 Griffinite 5th two who visited the winners’ circle . S 2003 New York Hero 6th George “Spider” Anderson won the 1889 Preakness aboard Buddhist .Willie Simms 2004 Song of the Sword 9th had two mounts, including a victory in Nancy Alberts 2002 Magic Weisner 2nd the 1898 Preakness with Sly Fox “Pike”. Lisa Lewis 2003 Kissin Saint 10th Barnes was second with Philosophy in Kristin Mulhall 2004 Imperialism 5th 1890, while the third and fourth place Linda Albert 2004 Water Cannon 10th finishers in the 1896 Preakness were Kathy Ritvo 2011 Mucho Macho Man 6th ridden by African-Americans (Alonzo Clayton—3rd with Intermission & Tony Note: Penny Lewis is the mother of Lisa Lewis Hamilton—4th on Cassette) .The final two to ride in the middle jewel are Wayne Barnett (Sparrowvon, 8th in 1985) and MARYLAND MY Kevin Krigger (Goldencents, 5th in 2013) . -

Kentucky Derby Winners Vs. Kentucky Derby Winners

KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS VS. KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS Winners of the Kentucky Derby have faced each other 43 times. The races have occurred 17 times in New York, nine in California, nine in Maryland, six in Kentucky, one in Illinois and one in Canada. Derby winners have run 1-2 on 12 occasions. The older Derby winner has prevailed 24 times. Three Kentucky Derby winners have been pitted against one another twice, including a 1-2-3 finish in the 1918 Bowie Handicap at Pimlico by George Smith, Omar Khayyam and Exterminator. Exterminator raced against Derby winners 15 times and finished ahead of his rose-bearing rivals nine times. His chief competitor was Paul Jones, who he beat in seven of 10 races while carrying more weight in each affair. Date Track Race Distance Derby Winner (Age, Weight) Finish Derby Winner (Age, Weight) Finish Nov. 2, 1991 Churchill Downs Breeders’ Cup Classic 1 ¼ M Unbridled (4, 126) 3rd Strike the Gold (3, 122) 5th June 26, 1988 Hollywood Park Hollywood Gold Cup H. 1 ¼ M Alysheba (4,126) 2nd Ferdinand (5, 125) 3rd April 17, 1988 Santa Anita San Bernardino H. 1 1/8 M Alysheba (4, 127) 1st Ferdinand (5, 127) 2nd March 6, 1988 Santa Anita Santa Anita H. 1 ¼ M Alysheba (4, 126) 1st Ferdinand (5, 127) 2nd Nov. 21, 1987 Hollywood Park Breeders’ Cup Classic 1 ¼ M Ferdinand (4, 126) 1st Alysheba (3, 122) 2nd Oct. 6, 1979 Belmont Park Jockey Club Gold Cup 1 ½ M Affirmed (4, 126) 1st Spectacular Bid (3, 121) 2nd Oct. 14, 1978 Belmont Park Jockey Club Gold Cup 1 ½ M Seattle Slew (4, 126) 2nd Affirmed (3, 121) 5th Sept. -

Setting the Standard

SETTING THE STANDARD A century ago a colt bred by Hamburg Place won a trio of races that became known as the Triple Crown, a feat only 12 others have matched By Edward L. Bowen COOK/KEENELAND LIBRARY Sir Barton’s exploits added luster to America’s classic races. 102 SPRING 2019 K KEENELAND.COM SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 102 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-102.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland Sir Barton, with trainer H. Guy Bedwell and jockey John Loftus, BLOODHORSE LIBRARY wears the blanket of roses after winning the 1919 Kentucky Derby. KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2019 103 SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 103 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-103.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland SETTING THE STANDARD ir Barton is renowned around the sports world as the rst Triple Crown winner, and 2019 marks the 100th an- niversary of his pivotal achievement in SAmerican horse racing history. For res- idents of Lexington, Kentucky — even those not closely attuned to racing — the name Sir Barton has an addition- al connotation, and a local one. The street Sir Barton Way is prominent in a section of the city known as Hamburg. Therein lies an additional link with history, for Sir Barton sprung from the famed Thoroughbred farm also known as Hamburg Place, which occupied the same land a century ago. The colt Sir Barton was one of four Kentucky Derby winners bred at Hamburg Place by a master of the Turf, one John E. Madden. Like the horse’s name, the name Madden also has come down through the years in a milieu of lasting and regen- erating fame. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

![Jockey Silks[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9845/jockey-silks-2-1349845.webp)

Jockey Silks[2]

RACING SILKS A MULTI- DISCIPLINARY LESSON ON DESIGN FOR K – 12TH WHAT ARE RACING SILKS? Silks are the uniform that a jockey wears during a race. The colorful jackets help the race commentator and the fans identify the horses on the track. WHO DECIDES WHAT THE SILKS LOOK LIKE? • The horse owner designs the silks. • Jockeys change their silks each race to reflect the owner of the horse they will be riding. • When you see two of the same silks in one race, that means that both of the horses belong to the same owner. • Each silks design is registered with the Jockey Club so that no two owners have the same silks. This ensures that each design is unique. A FEW JOCKEY CLUB DESIGN RULES • It costs $100 per year to register your silks. You must renew the registration annually. Colors are renewable on December 31st of the year they are registered. • Front and back of silks must be identical, except for the seam design. • Navy blue is NOT an available color. • A maximum of two colors is allowed on the jacket and two on the sleeves for a maximum of four colors. • You may have an acceptable emblem or up to three initials on the ball, yoke, circle or braces design. You may have one initial on the opposite shoulder of the sash, box frame or diamond design. COLORS AND PATTERNS Silks can be made up of a wide variety of colors and shapes, with patterns like circles, stars, squares, and triangles. We know colors and patterns mean things, and sometimes horse owners draw inspirations for their design from their childhood, surroundings, favorite things, and careers. -

Kentucky Derby

The Legacy and Traditions of Churchill Downs and the Kentucky Derby The Kentucky Derby The Kentucky Derby has taken place annually in Louis- ville, Kentucky since 1875. It was started by Meriwether Lewis Clark, Jr. at his track he called Churchill Downs, and it has run continuously since that first race. This first jewel of the Triple Crown has produced famous winners, with thirteen of these winners gaining that Triple Crown title. Lewis limited the Derby to only 3-year old horses. The race has evolved and grown over time and has changed since its first running, remaining an important event for more than a century. Through the study of the Derby’s influential historic traditions, notable winners and horse farms in Kentucky, and its profound cultural TABLE OF CONTENTS impact, this program will identify and explore these dif- Background and History…..2 ferent aspects that all contribute to the excitement and legacy of the “most exciting two minutes in sports.” Curriculum Standards…..3 Traditions ................ 4-8 Triple Crown ............ 9 Derby Winners ........ 10-11 Notable Horse Farms….12-13 Significant Figures…...15 Bibliography………….16 Image list…………….17-18 Derby Activities…….19-22 To replicate the races he witnessed in Europe, Meri- wether Lewis Clark Jr., the grandson of explorer Wil- liam Clark, created three races in the United States that resembled those he’d attended in Europe. The first meet was in May of 1875. Family ties to the horse racing world led Clark to his purchase of what would become Churchill Downs, named after his uncles, John and Henry Churchill in 1883. -

Reading Bede As Bede Would Read

Reading Bede as Bede would read Author: Sally Shockro Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1746 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History READING BEDE AS BEDE WOULD READ a dissertation by SALLY SHOCKRO submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2008 © copyright by SALLY JEAN SHOCKRO 2008 Dissertation Abstract Reading Bede as Bede Would Read Sally Shockro Robin Fleming, Advisor 2008 Early medieval readers read texts differently than their modern scholarly counterparts. Their expectations were different, but so, too, were their perceptions of the purpose and function of the text. Early medieval historians have long thought that because they were reading the same words as their early medieval subjects they were sharing in the same knowledge. But it is the contention of my thesis that until historians learn to read as early medieval people read, the meanings texts held for their original readers will remain unknown. Early medieval readers maintained that important texts functioned on many levels, with deeper levels possessing more layers of meaning for the reader equipped to grasp them. A good text was able, with the use of a phrase or an image, to trigger the recall of other seemingly distant, yet related, knowledge which would elucidate the final spiritual message of the story. For an early medieval reader, the ultimate example of the multi-layered text was the Bible. -

The Field Citation Program Under the Clean Air Act: Can EPA Apply It to Federal Facilities?

William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 22 (1997-1998) Issue 1 Article 3 October 1997 The Field Citation Program Under the Clean Air Act: Can EPA Apply it to Federal Facilities? Kevin J. Luster Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr Part of the Environmental Law Commons Repository Citation Kevin J. Luster, The Field Citation Program Under the Clean Air Act: Can EPA Apply it to Federal Facilities?, 22 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 71 (1997), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmelpr/vol22/iss1/3 Copyright c 1997 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr THE FIELD CITATION PROGRAM UNDER THE CLEAN AIR ACT: CAN EPA APPLY IT To FEDERAL FACILITIES? MAJOR KEVIN J. LUSTER* I. INTRODUCTION In 1990, Congress amended the federal enforcement provision of the Clean Air Act ("CAA" or the "Act").' The amendment expanded the Environmental Protection Agency's ("EPA" or the "Agency") enforcement options and considerably enhanced the Agency's administrative enforcement powers. In section 11 3(d)(3), Congress authorized the Administrator of EPA to implement, through regulations, a field citation program for minor viola- tions of the CAA.3 On May 3, 1994, EPA published a notice of proposed rulemaking for a field citation program pursuant to CAA section 1 13(d)(3). 4 EPA intends to apply the program to federal agencies, and it expects to publish the final rule either in late March or early April of 1998.' This will be the first program under which EPA assesses civil penalties against a unit ' Major Kevin J.