Digital Audio Recorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KLOS March 30Th 2014 Denny Laine

1 1 2 2 3 9AM I’m sad to say that I’m dedicating this first couple of songs here to our dear friend Stan …you know him as Stan the Hot Sauce Man….whose Mom Marion passed away yesterday…Now we got to know Marion here on BWTB quite well…as she came hung out with us more than a few times She also made me that British Flag quilt blanket And BWTB pillow…that we often talked about…she came down to all the events at Capitol Records…Just Imagine shows…everyone loved her…and she will certainly be missed…and here is Marion’s favorite Beatles song. 3 4 The Beatles - If I Fell - A Hard Day’s Night (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John and Paul John Lennon’s stunning ballad “If I Fell” was by far the most complex song he had written to date. It could be considered a progression from “This Boy” with its similar chord structure and intricate harmonies by John and Paul, recorded – at their request – together on one microphone. Performed live on their world tour throughout the summer of 1964. Completed in 15 takes on February 27, 1964. Flip side of “And I Love Her” in the U.S. On U.S. album: A Hard Day’s Night - United Artists LP Something New - Capitol LP The Beatles - In My Life - Rubber Soul (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocals: John with Paul Recorded October 18, 1965 and written primarily by John, who called it his “first real major piece of work.” Of all the Lennon-McCartney collaborations only two songs have really been disputed by John and Paul themselves -- “Eleanor Rigby” and “In My Life.” Both agree that the lyrics are 100% Lennon, but John says Paul helped on the musical bridge, while Paul recalls writing the entire melody on John’s Mellotron. -

Vocals Syllabus

VOCALS SYLLABUS BEYONCÉ Qualification specifications for graded exams from 2018 AEROSMITH BLONDIE THE ROLLING STONES TAYLOR SWIFT RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS DUSTY SPRINGFIELD AMY WINEHOUSE QUEEN DAVID BOWIE THE XX OASIS SIA U2 WHAT’S CHANGED? This syllabus features the following changes from the 2015–2017 syllabus: New selection of songs at all levels, expertly arranged for the grade and in a wide range of styles Revised marking criteria, providing examiners, teachers and candidates with increased detail on how exams are marked (see pages 36–39) Revised parameters for own-choice songs (see pages 22–27) Revised requirements for using a microphone when performing songs Technical focus songs now feature two technical elements Band exams are no longer offered KEEP UP TO DATE WITH OUR SYLLABUSES Please check trinityrock.com to make sure you are using the current version of the syllabus and for the latest information about our Rock & Pop exams. You can also check out our syllabuses and graded songbooks for: Bass Drums Guitar Keyboards OVERLAP ARRANGEMENTS This syllabus is valid from 1 January 2018. The 2015–2017 syllabus will remain valid until 31 December 2018, giving a one year overlap. During this time, candidates may present songs from the 2015–2017 syllabus or the syllabus from 2018, but not both. Candidates should indicate which syllabus they are presenting on the appointment form handed to the examiner at the start of the exam. VOCALS SYLLABUS Qualification specifications for graded exams from 2018 Trinity College London trinitycollege.com -

Media Draft Appendix

Media Draft Appendix October, 2001 P C Hariharan Media Historical evidence for written records dates from about the middle of the third millennium BC. The writing is on media1 like a rock face, cave wall, clay tablets, papyrus scrolls and metallic discs. Writing, which was at first logographic, went through various stages such as ideography, polyphonic syllabary, monophonic syllabary and the very condensed alphabetic systems used by the major European languages today. The choice of the medium on which the writing was done has played a significant part in the development of writing. Thus, the Egyptians used hieroglyphic symbols for monumental and epigraphic writing, but began to adopt the slightly different hieratic form of it on papyri where it coexisted with hieroglyphics. Later, demotic was derived from hieratic for more popular uses. In writing systems based on the Greek and Roman alphabet, monumental writing made minimal use of uncials and there was often no space between words; a soft surface, and a stylus one does not have to hammer on, are conducive to cursive writing. Early scribes did not have a wide choice of media or writing instruments. Charcoal, pigments derived from mineral ores, awls and chisels have all been used on hard media. Cuneiform writing on clay tablets, and Egyptian hieroglyphic and hieratic writing on papyrus scrolls, permitted the use of a stylus made from reeds. These could be shaped and kept in writing trim by the scribe, and the knowledge and skill needed for their use was a cherished skill often as valuable as the knowledge of writing itself. -

Dual Digital Audio Tape Deck OWNER's MANUAL

» DA-302 Dual Digital Audio Tape Deck OWNER’S MANUAL D00313200A Important Safety Precautions CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALI- Ü FIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol, within equilateral triangle, is intended to alert the user to the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the product’s enclosure ÿ that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the pres- ence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature Ÿ accompanying the appliance. This appliance has a serial number located on the rear panel. Please record the model number and WARNING: TO PREVENT FIRE OR SHOCK serial number and retain them for your records. Model number HAZARD, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS Serial number APPLIANCE TO RAIN OR MOISTURE. For U.S.A Important (for U.K. Customers) TO THE USER DO NOT cut off the mains plug from this equip- This equipment has been tested and found to com- ment. If the plug fitted is not suitable for the power ply with the limits for a Class A digital device, pur- points in your home or the cable is too short to suant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are reach a power point, then obtain an appropriate designed to provide reasonable protection against safety approved extension lead or consult your harmful interference when the equipment is operat- dealer. -

MINIDISC MANUAL V3.0E Table of Contents

MINIDISC MANUAL V3.0E Table of Contents Introduction . 1 1. The MiniDisc System 1.1. The Features . 2 1.2. What it is and How it Works . 3 1.3. Serial Copy Management System . 8 1.4. Additional Features of the Premastered MD . 8 2. The production process of the premastered MD 2.1. MD Production . 9 2.2. MD Components . 10 3. Input components specification 3.1. Sound Carrier Specifications . 12 3.2. Additional TOC Data / Character Information . 17 3.3. Label-, Artwork- and Print Films . 19 3.4. MiniDisc Logo . 23 4. Sony DADC Austria AG 4.1. The Company . 25 5. Appendix Form Sheets Introduction T he quick random access of Compact Disc players has become a necessity for music lovers. The high quality of digital sound is now the norm. The future of personal audio must meet the above criteria and more. That’s why Sony has created the MiniDisc, a revolutionary evolution in the field of digital audio based on an advanced miniature optical disc. The MD offers consumers the quick random access, durability and high sound quality of optical media, as well as superb compactness, shock- resistant portability and recordability. In short, the MD format has been created to meet the needs of personal music entertainment in the future. Based on a dazzling array of new technologies, the MiniDisc offers a new lifestyle in personal audio enjoyment. The Features 1. The MiniDisc System 1.1. The Features With the MiniDisc, Sony has created a revolutionary optical disc. It offers all the features that music fans have been waiting for. -

AW2400 Owner's Manual

Owner’s Manual EN FCC INFORMATION (U.S.A.) 1. IMPORTANT NOTICE: DO NOT MODIFY THIS devices. Compliance with FCC regulations does not guar- UNIT! antee that interference will not occur in all installations. If This product, when installed as indicated in the instruc- this product is found to be the source of interference, tions contained in this manual, meets FCC requirements. which can be determined by turning the unit “OFF” and Modifications not expressly approved by Yamaha may “ON”, please try to eliminate the problem by using one of void your authority, granted by the FCC, to use the prod- the following measures: uct. Relocate either this product or the device that is being 2. IMPORTANT: When connecting this product to acces- affected by the interference. sories and/or another product use only high quality Utilize power outlets that are on different branch (circuit shielded cables. Cable/s supplied with this product MUST breaker or fuse) circuits or install AC line filter/s. be used. Follow all installation instructions. Failure to fol- In the case of radio or TV interference, relocate/reorient low instructions could void your FCC authorization to use the antenna. If the antenna lead-in is 300 ohm ribbon this product in the USA. lead, change the lead-in to co-axial type cable. 3. NOTE: This product has been tested and found to com- If these corrective measures do not produce satisfactory ply with the requirements listed in FCC Regulations, Part results, please contact the local retailer authorized to dis- 15 for Class “B” digital devices. -

Direct-To-Master Recording

Direct-To-Master Recording J. I. Agnew S. Steldinger Magnetic Fidelity http://www.magneticfidelity.com info@magneticfidelity.com July 31, 2016 Abstract Direct-to-Master Recording is a method of recording sound, where the music is performed entirely live and captured directly onto the master medium. This is usually done entirely in the analog domain using either magnetic tape or a phonograph disk as the recording medium. The result is an intense and realistic sonic image of the performance with an outstandig dynamic range. 1 The evolution of sound tracks can now also be edited note by note to recording technology compile a solid performance that can be altered or \improved" at will. Sound recording technology has greatly evolved This technological progress has made it pos- since the 1940's, when Direct-To-Master record- sible for far less competent musicians to make ing was not actually something special, but more a more or less competent sounding album and like one of the few options for recording music. for washed out rock stars who, if all put in the This evolution has enabled us to do things that same room at the same time, would probably would be unthinkable in those early days, such as murder each other, to make an album together. multitrack recording, which allows different in- Or, at least almost together. This ability, how- struments to be recorded at different times, and ever, comes at a certain cost. The recording pro- mixed later to create what sounds like a perfor- cess has been broken up into several stages, per- mance by many instruments at the same time. -

Model DV6500 User Guide Super Audio CD / DVD Player

E59M5UD.qx3 04.7.16 7:50 PM Page 1 Model DV6500 User Guide Super Audio CD / DVD Player CLASS 1 LASER PRODUCT E59M5UD.qx3 04.7.16 7:50 PM Page 2 TO REDUCE THE RISK OF FIRE OR ELECTRIC SHOCK, WARNING DO NOT EXPOSE THIS PRODUCT TO RAIN OR MOISTURE. The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the CAUTION presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK product’s enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude DO NOT OPEN to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. CAUTION: The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE intended to alert the user to the presence of important COVER (OR BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. literature accompanying the product. CAUTION: TO PREVENT ELECTRIC SHOCK, MATCH WIDE BLADE OF PLUG TO WIDE SLOT, FULLY INSERT. ATTENTION: POUR ÉVITER LES CHOC ÉLECTRIQUES, INTRODUIRE LA LAME LA PLUS LARGE DE LA FICHE DANS LA BORNE CORRESPONDANTE DE LA PRISE ET POUSSER JUSQU’AU FOND. NOTE: Operating Environment This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits Operating environment temperature and humidity: for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. +5 C to +35 C (+41 F to +95 F); less than 85%RH (cooling vents not These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against blocked) Do not install in the following locations harmful interference in a residential installation. -

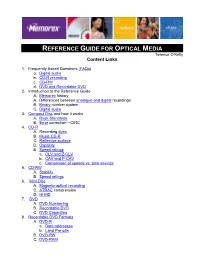

REFERENCE GUIDE for OPTICAL MEDIA Terence O’Kelly Content Links

REFERENCE GUIDE FOR OPTICAL MEDIA Terence O’Kelly Content Links 1. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) a. Digital audio b. CD-R recording c. CD-RW d. DVD and Recordable DVD 2. Introduction to the Reference Guide A. Memorex history A. Differences between analogue and digital recordings B. Binary number system C. Digital audio 3. Compact Disc and how it works A. Book Standards B. Error correction—CIRC 4. CD-R A. Recording dyes B. Music CD-R C. Reflective surface D. Capacity E. Speed ratings a. CLV and Z-CLV b. CAV and P-CAV c. Comparison of speeds vs. time savings 5. CD-RW A. Stability B. Speed ratings 6. Mini-Disc A. Magneto-optical recording C. ATRAC compression D. Hi-MD 7. DVD A. DVD Numbering B. Recordable DVD C. DVD Capacities 8. Recordable DVD Formats A. DVD-R a. Data addresses b. Land Pre-pits B. DVD-RW C. DVD-RAM a. Data addresses b. Cartridge types D. DVD+R a. Data addresses b. ADIP E. DVD+RW 9. Recording onto DVD discs A. VR Recording onto DVD--+VR and –VR B. CPRM C. Capacities of recordable DVD discs a. Capacities in terms of time b. Set-top recorder time chart D. Double-Layer Discs E. Recording Speeds 10. Blue Laser Recording A. High Definition Video B. Blu-ray versus HD DVD C. Laser wavelengths a. Numerical aperture b. Comparison of High Definition Proposals 11. Life-time Expectations of Optical Media 12. Care and Handling of Optical Media 2 FAQs about Optical Media There is a great deal of misinformation, hype, and misunderstanding in the field of optical media. -

IN PRACTICE Transport/Tape, and These Are Luxuries Few of Us Can Afford with PCM-1610S and PCM- 1630S

something we do not really need. Tandy make some inexpensive moulded 2 -way headphone splitter leads which can be rewired with a couple of XLRs to make reliable headphone socket -to -line driver leads -I have not always had the best of luck with home-made headphone -to- two-XLR leads, they seem to fall apart at the jack end after a couple of months. The best setting corresponding to our normal headroom practice was with the headphone output level set to around 3 o'clock (ie slightly below maximum) and the input levels to give unity gain overall in-to out. In the fullness of time I shall probably change a feedback resistor in the headphone output amplifier to reduce the gain, so we can operate the line -out with the headphone volume control set to maximum, which is easier to set consistently. These interfacing details will be nothing new to those experienced with the Sony PCM-Fl or 701, and although unbalanced, they cause few troubles. Metering is via horizontal fluorescent bargraphs, with 0 dB on the display corresponding to 2 dB below peak-bits (digital end-stop). A red over light tells you when you have gone over the top, and the 2 dB 'overlap' is very helpful in optimising peak recording level. Having the audio processing and tape transport in one box about the same size as a sophisticated R-DAT domestic video cassette deck (it weighs just under 12 kg) is much more convenient than lugging around a PCM-1630 and U- matic. With two DATs on a session one has automatically a full backup of A/D and D/A circuitry as well as tape - IN PRACTICE transport/tape, and these are luxuries few of us can afford with PCM-1610s and PCM- 1630s. -

![MZ-R501\3234036131MZR501UCE\01COV- MZR501UCE\00GB01COV-CED.Fm] Masterpage:Right](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7319/mz-r501-3234036131mzr501uce-01cov-mzr501uce-00gb01cov-ced-fm-masterpage-right-977319.webp)

MZ-R501\3234036131MZR501UCE\01COV- MZR501UCE\00GB01COV-CED.Fm] Masterpage:Right

filename[\\Ww001\WW001\ON GOING\MZ-R501\3234036131MZR501UCE\01COV- MZR501UCE\00GB01COV-CED.fm] masterpage:Right 00GB01COV-CED.fm Page 1 Monday, November 5, 2001 1:37 PM 3-234-036-13(1) Portable MiniDisc Recorder Operating Instructions WALKMAN and are trademarks of Sony Corporation. MZ-R501/R501PC/R501DPC © 2001 Sony Corporation model name1[MZ-R501/R501PC/R501DPC] model name2[MZ-----] [3-234-036-13(1)] Certain countries may regulate disposal of WARNING battery used to power this product. To prevent fire or shock hazard, do Please consult with your local authority. not expose the unit to rain or moisture. For customers in the USA To avoid electrical shock, do not Owner’s Record open the cabinet. Refer servicing to The serial number is located at the rear of qualified personnel only. the disc compartment lid and the model number is located at the top and bottom. Do not install the appliance in a Record the serial number in the space confined space, such as a bookcase or provided below. Refer to them whenever you call upon your Sony dealer regarding built-in cabinet. this product. Model No. To prevent fire, do not cover the Serial No. ventilation of the apparatus with news papers, table cloths, curtains, etc. And This equipment has been tested and found don’t place lighted candles on the to comply with the limits for a Class B apparatus. digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to To prevent fire or shock hazard, do not provide reasonable protection against place objects filled with liquids, such as harmful interference in a residential vases, on the apparatus. -

TR Operation Guide

Operation Guide E 2 To ensure long, trouble-free operation, THE FCC REGULATION WARNING (for U.S.A.) please read this manual carefully. This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Precautions Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protec- tion against harmful interference in a residential installation. This Location equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency Using the unit in the following locations can result energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communi- in a malfunction. cations. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not • In direct sunlight occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does cause • Locations of extreme temperature or humidity harmful interference to radio or television reception, which can • Excessively dusty or dirty locations be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is • Locations of excessive vibration encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following measures: Power supply • Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. Please connect the designated AC/AC power sup- • Increase the separation between the equipment and receiver. ply to an AC outlet of the correct voltage. Do not • Connect the equipment into an outlet on a circuit different from that to which the receiver is connected. connect it to an AC outlet of voltage other than that • Consult the dealer or an experienced radio/TV technician for for which your unit is intended.