Arranging for School Jazz Ensembles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Music Standards

5th Grade Singing alone and with others Standard 1 Students sing alone or in groups, on pitch and in rhythm, using good tone, diction, breath control, and posture while maintaining a steady tempo. They sing from memory a variety of song repertoire, including ostinatos, partner songs, rounds, and music of many cultures and styles. They sing accurately with appropriate dynamics, breath control, phrasing, and interpretation. Students in fifth grade sing in groups, blending vocal sounds, matching dynamics, and following the conductor. 5.1.1 Sing warm-ups that stress diction, posture, and an appropriate singing tone. 5.1.2 Sing a round with appropriate dynamics, phrasing and interpretations. Maintain an independent part and keep a steady beat. 5.1.3 Sing a memorized song in a foreign language. 5.1.4 Follow the conductor. Playing an instrument alone and with others Standard 2 Students perform accurately, independently, and expressively on an instrument, either alone or in an ensemble. They echo easy rhythmic, melodic, and chordal patterns. Students perform in groups, blending instrumental tones, matching dynamics, and responding to the conductor. They perform instrumental parts while other students sing or play different parts. 5.2.1 Play an ostinato part independently. 5.2.2 Play a melody or rhythm in the proper tempo, using appropriate dynamics. 5.2.3 Play an accompaniment to a class or group song. Example: On a keyboard, guitar, mallet instrument, or autoharp, play an ostinato pattern while the group sings. 5.2.4 Play a variety of music of various cultures and styles. 5.2.5 Maintain an independent part on an instrument in a group while following the conductor. -

FMEA 2014 Professional Development Conference January 9, 2014 2:45 Pm

Navigating the Murky Waters: A Guide to Making Sense of Vocal Jazz Ensemble Charts Andrew N. Dahan [email protected] University of Miami Frost School of Music FMEA 2014 Professional Development Conference January 9, 2014 2:45 pm A Brief History of Vocal Jazz As jazz has evolved in our country, many vocalists have contributed to the art form. Many of us already know that singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday (to name a few) brought different ideas and styles to their performances, which in turn made them stand out in the jazz world. What many people may not know is Louis Armstrong is considered to be the person responsible for establishing singing as a part of the jazz scene. He also is the person responsible for setting the precedent that vocalists take a more “instrumental” approach when singing jazz. The post-war era brought the emergence of the jazz ensemble, or big band. Vocalists were often featured with these bands and shortly thereafter, small vocal jazz ensembles like Lambert Hendricks & Ross began to surface. By the 70’s, many small ensembles including the Singers Unlimited and the Manhattan Transfer really had established notoriety in the jazz world, and groups such as the New York Voices, The Real Group, and Vertical Voices continue the tradition today. The first school-affiliated vocal jazz ensembles as we know them today began in Community Colleges in the Pacific Northwest. Since music often wasn’t available for that type of ensemble, they sang actual jazz band charts that had been rearranged for singers. -

Easy Jazz Guitar Progressions

Easy Jazz Guitar Progressions 12 Essential Progressions for Jazz Guitar Written By: Matthew Warnock Published By: Guitar for Life LLC Copyright 2017 Guitar for Life LLC mattwarnockguitar.com 2 Table of Contents How to Use This eBook Introduction to Chord Progressions Major ii V I Progression Minor ii V I Progression Major I VI ii V Progression Minor I bIII ii V Progression Mixed ii V I 1 Progression Mixed ii V I 2 Progressions Backdoor ii V Progression Take the A Train Rhythm Changes Bridge Turnaround to the iim7 Chord IVmaj7 to Imaj7 Turnaround Minor Cliché mattwarnockguitar.com 3 How to Use This eBook Before you dive into this material, take a minute to learn how to get the most out of this eBook in your practice routine. The first thing to know, is that jazz progressions are not usually thought of as “easy” as the book’s title suggests. But, with the right practice approach, you can make any progression sound easy in your comping and soloing. By understanding their construction, and working fun and essential exercises, any jazz progression can be easy to outline in your playing. The material in this eBook does just this, breaks down seemingly difficult progressions into easy to understand concepts. Doing so builds your confidence and allows you to outline any of these progressions in jazz standards with ease. When learning any progression in this eBook, work it in the following ways to get the most out of your practice time. Ø Learn the chords in the given key. Ø Work those chords over the backing track. -

Ebook Download the Mccoy Tyner Collection

THE MCCOY TYNER COLLECTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK McCoy Tyner | 120 pages | 01 Nov 1992 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9780793507474 | English | Milwaukee, United States The Mccoy Tyner Collection PDF Book Similar Artists See All. There's magic in the air, or at the very least a common ground of shared values that makes this combination of two great musicians turn everything golden. That's not to say their progressive ideas are completely harnessed, but this recording is something lovers of dinner music or late-night romantic trysts will equally appreciate. McCoy Tyner. Extensions - McCoy Tyner. Tyner died on March 6, at his home in New Jersey. They sound empathetic, as if they've played many times before, yet there are enough sparks to signal that they're still unsure of what the other will play. Very highly recommended. Albums Live Albums Compilations. Cart 0. If I Were a Bell. On this excellent set, McCoy Tyner had the opportunity for the first time to head a larger group. McCoy later said, Bud and Richie Powell moved into my neighborhood. He also befriended saxophonist John Coltrane, then a member of trumpeter Miles Davis' band. A flow of adventurous, eclectic albums followed throughout the decade, many featuring his quartet with saxophonist Azar Lawrence, including 's Song for My Lady, 's Enlightenment, and 's Atlantis. McCoy Tyner Trio. See the album. Throughout his career, Tyner continued to push himself, arranging for his big band and releasing Grammy-winning albums with 's Blues for Coltrane: A Tribute to John Coltrane and 's The Turning Point. However, after six months with the Jazztet, he left to join Coltrane's soon-to-be classic quartet with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. -

Jazz Album Picks

Jazz Series Pilot TOP 407* LBUMS Taped At CBS, L.A. LOS ANGELES — “Stars of Jazz — Nostalgia & New Sounds," a proposed new Weeks Weeks television series showcasing mainstream On un Chart as well as younger jazz artists, its 3/25 Chari 3/25 taped pilot Feb. 19 at CBS-TV studios here. 1 WEEKEND IN L.A. GEORGE BENSON 21 EASY LIVING The first one-hour program was hosted SONNY ROLLINS (Milestone M-9080) 23 9 (Warner Bros. 2WB 3139) 1 9 by Bobby Troup and featured perfor- THE BIJOU 22 MULTIPLICATION mances by Hadley Caliman, Sarah 2 LIVE AT 14 16 GROVER WASHINGTON JR. ERIC GALE (Columbia JC 34938) Vaughan, the Billy May Band and theTeddy (Kudu KUX-3637 MZ) 2 15 Buckner Band. 23 RUBY, RUBY (A&M SP 19 24 3 RAINBOW SEEKER GATO BARBIERI 4655) According to executive producer JOE SAMPLE (ABC AA-1050) 3 8 LAWS AT THE PAVILLION — Columbia Charles Allen, negotiations are now un- 24 SAY IT WITH SILENCE — recording artist Hubert Laws was con- derway for a series sponsor. 4 HOLD ON HUBERT LAWS (Columbia JC 35022) 1 NOEL POINTER gratulated at a reception in his honor after The series is produced by James Carlton (United Artists UA-LA 848H) 4 8 25 HAVANA CANDY his recent performance at the Dorothy Baker and directed by Mark Massair. Music PATTI AUSTIN (CTI 7-5006) 24 20 Chandler Pavillion. Pictered (l-r) are: Dr. coordinator is Don Bagely, in conjunction 5 FEELS SO GOOD CHUCK MANGIONE (A&M SP 4658) 5 22 26 TIGHTROPE George Butler, vice president jazz & with consultant Bobby Knight. -

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Nafme Council for Guitar

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Many schools today offer guitar classes and guitar ensembles as a form of music instruction. While guitar is a popular music choice for students to take, there are many teachers offering instruction where guitar is their secondary instrument. The NAfME Guitar Council collaborated and compiled lists of Guitar Best Practices for each year of study. They comprise a set of technical skills, music experiences, and music theory knowledge that guitar students should know through their scholastic career. As a Guitar Council, we have taken careful consideration to ensure that the lists are applicable to middle school and high school guitar class instruction, and may be covered through a wide variety of method books and music styles (classical, country, folk, jazz, pop). All items on the list can be performed on acoustic, classical, and/or electric guitars. NAfME Council for Guitar Education Best Practices Outline for a Year One Guitar Class YEAR ONE - At the completion of year one, students will be able to: 1. Perform using correct sitting posture and appropriate hand positions 2. Play a sixteen measure melody composed with eighth notes at a moderate tempo using alternate picking 3. Read standard music notation and play on all six strings in first position up to the fourth fret 4. Play melodies in the keys C major, a minor, G major, e minor, D major, b minor, F major and d minor 5. Play one octave scales including C major, G major, A major, D major and E major in first position 6. -

Classical Music from the Late 19Th Century to the Early 20Th Century: the Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2019 May 1st, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM Classical Music from the Late 19th Century to the Early 20th Century: The Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound Ashley M. Christensen Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Music Theory Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Christensen, Ashley M., "Classical Music from the Late 19th Century to the Early 20th Century: The Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound" (2019). Young Historians Conference. 13. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2019/oralpres/13 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CLASSICAL MUSIC FROM THE LATE 19th CENTURY TO THE EARLY 20th CENTURY: THE CREATION OF A DISTINCT AMERICAN MUSICAL SOUND Marked by the conflict of the Civil War, the late 19th century of American history marks an extremely turbulent time for the United States of America. As the young nation reached the second half of the century, idle threats of a Southern secession from the union bloomed into an all-encompassing conflict. However, through the turbulence of the war, American music persisted. Strengthened in battle, the ideas of a reconstructed American national identity started to form a distinctly different American culture and way of life. This is reflected in the nation’s shift in the music written after the war. -

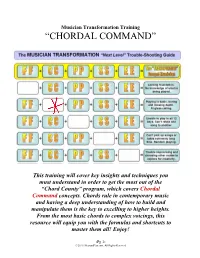

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

Constructing Jazz Lines. Taxonomy, Vocabulary, Grammar

Die internationale Jazzforschung hat sich in den vergangenen Jahrzehnten zahlreiche neue Fragestellungen und Forschungsan- sätze erschlossen. Die dreizehn Beiträge des Tagungsbandes wid- Jazzforschung heute. men sich Themen, Methoden und Desideraten der gegenwärtigen wissenschaftlichen Auseinandersetzung mit dem Jazz. Zudem werden Perspektiven des künstlerischen Forschens im Jazz und Martin Pfleiderer (Jg. 1967) studierte Musikwissenschaft, der Ausbildung von Jazzmusikern und -forschern diskutiert. Philosophie und Soziologie. Seit 2009 lehrt er Geschichte des Jazz und der populären Musik am Institut für Musik- wissenschaft Weimar-Jena. Er hat zahlreiche Aufsätze zum Lorem ipsumThemen, dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisici elit, sed eiusmodMethoden, Perspektiven Jazz veröffentlicht und ist darüber hinaus als Jazzsaxopho- tempor incidunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim nist aktiv. veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequat. Quis aute iure reprehenderit in voluptate velit Jazzforschung heute esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint obcaecat cu- piditat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id Wolf-Georg Zaddach (Jg. 1985) studierte Musikwissen- est laborum. schaft, Kulturmanagement und Neuere Geschichte in Weimar/Jena sowie Musikmanagement und Jazzgitarre in Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisici elit, sed eiusmod Prag. Er lehrt seit 2011 am Institut für Musikwissenschaft (Hg.) tempor incidunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim Weimar-Jena sowie seit 2017 am British and Irish Modern herausgegeben von Martin Pfleiderer veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquid ex ea Music Institute Berlin. 2018 wurde er mit einer Doktor- commodi consequat. Quis aute iure reprehenderit in voluptate velit arbeit über Heavy Metal in der DDR promoviert. -

Music Content Analysis : Key, Chord and Rhythm Tracking In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS MUSIC CONTENT ANALYSIS : KEY, CHORD AND RHYTHM TRACKING IN ACOUSTIC SIGNALS ARUN SHENOY KOTA (B.Eng.(Computer Science), Mangalore University, India) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 Acknowledgments I am grateful to Dr. Wang Ye for extending an opportunity to pursue audio research and work on various aspects of music analysis, which has led to this dissertation. Through his ideas, support and enthusiastic supervision, he is in many ways directly responsible for much of the direction this work took. He has been the best advisor and teacher I could have wished for and it has been a joy to work with him. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Terence Sim for his support, in the role of a mentor, during my first term of graduate study and for our numerous technical and music theoretic discussions thereafter. He has also served as my thesis examiner along with Dr Mohan Kankanhalli. I greatly appreciate the valuable comments and suggestions given by them. Special thanks to Roshni for her contribution to my work through our numerous discussions and constructive arguments. She has also been a great source of practical information, as well as being happy to be the first to hear my outrage or glee at the day’s current events. There are a few special people in the audio community that I must acknowledge due to their importance in my work.