A Country Full of Holes TREVOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KINGSWINFORD (Inc

HITCHMOUGH’S BLACK COUNTRY PUBS KINGSWINFORD (Inc. Himley, Wall Heath) 3rd. Edition - © 2015 Tony Hitchmough. All Rights Reserved www.longpull.co.uk INTRODUCTION Well over 40 years ago, I began to notice that the English public house was more than just a building in which people drank. The customers talked and played, held trips and meetings, the licensees had their own stories, and the buildings had experienced many changes. These thoughts spurred me on to find out more. Obviously I had to restrict my field; Black Country pubs became my theme, because that is where I lived and worked. Many of the pubs I remembered from the late 1960’s, when I was legally allowed to drink in them, had disappeared or were in the process of doing so. My plan was to collect any information I could from any sources available. Around that time the Black Country Bugle first appeared; I have never missed an issue, and have found the contents and letters invaluable. I then started to visit the archives of the Black Country boroughs. Directories were another invaluable source for licensees’ names, enabling me to build up lists. The censuses, church registers and licensing minutes for some areas, also were consulted. Newspaper articles provided many items of human interest (eg. inquests, crimes, civic matters, industrial relations), which would be of value not only to a pub historian, but to local and social historians and genealogists alike. With the advances in technology in mind, I decided the opportunity of releasing my entire archive digitally, rather than mere selections as magazine articles or as a book, was too good to miss. -

The Midlands Ultimate Entertainment Guide

Shropshire Cover Online.qxp_cover 27/10/2015 15:30 Page 1 THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE SHROPSHIRE ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 359 NOVEMBER 2015 DAVID WALLIAMS talks Gansta Granny interview inside... CHRIS RAMSEY All Growed Up at Theatre Severn MASKS AND PUPPETS new exhibition promises something for everyone ALAN INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS EVENTS DAVIESON TOUR FOOD & DRINK & MUCH MORE! Belgrade (FP) OCT 2015.qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 20:59 Page 1 Contents November Region 2 .qxp_Layout 1 26/10/2015 18:16 Page 1 November 2015 Brave New World Aldous Huxley’s vision of the future in Wolves, page 33 The Grahams Lee Mead Antiques For Everyone Glory Bound at talks about Some Enchanted Winter Fair at the NEC Henry Tudor House page 11 Evening interview page 6 page 71 INSIDE: 4. News 11. Music 24. Comedy 29. Theatre 45. Dance 47. Film 67. Visual Arts 73. Days Out 81. Food @whatsonwolves @whatsonstaffs @whatsonshrops Birmingham What’s On Magazine Staffordshire What’s On Magazine Shropshire What’s On Magazine Publishing + Online Editor-in-Chief: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 WhatsOn Editorial: Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 MAGAZINE GROUP Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Chris Eldon Lee, Heather Kincaid, David Vincent, Helen Stallard, Clare Higgins, Offices: Wynner House, Kieran Johnson Managing Director: Paul Oliver, Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell, Chris Atherton Bromsgrove St, Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 Birmingham B5 6RG This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine. -

Marti Pellow

Midlands Cover - August CA_Layout 1 25/07/2013 12:28 Page 1 MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS THE MIDLANDS ESSENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE ISSUE 332 AUGUST 2013 AUGUST www.whatsonlive.co.uk £1.80 ISSUE 332 AUGUST 2013 MARTI PELLOW INTERVIEW INSIDE... PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART What’sOn MAGAZINE GROUP ISSN 1462-7035 grand_whatson FP Aug_Layout 1 25/07/2013 13:36 Page 1 Great Theatre at the Grand! MON 19 - SAT 31 AUGUST SAT 14 - SUN 15 SEPTEMBER #### #### SOUTHERN LIVERPOOL DAILY ECHO ECHO “Possibly the best gala evening of musical theatre you are ever likely to see” THE PUBLIC REVIEWS MON 16 - SAT 21 SEPTEMBER TUES 24 - SAT 28 SEPTEMBER TUES 8 - SAT 12 OCTOBER ‘I LOVED EVERY MOMENT’ An amateur production South StaffS MuSical theatre coMpany DAILY TELEGRAPH proudly preSentS the rodgerS and haMMerStein claSSic BILL KENWRIGHT AND LAURIE MANSFIELD IN ASSOCIATION WITH UNIVERSAL MUSIC PRESENT An amateur production “Some excellent singing and acting performances” Express & Star Guys and Dolls 2011 “A cast of 40 hit the peaks of performance” Birmingham Mail The Sound of Music 2012 ‘A GREAT ROCKIN’ EVENING’ DAILY EXPRESS Please note this show contains nudity and strong language. TUES 15 - SAT 19 OCTOBER TUES 22 - SAT 26 OCTOBER SAT 7 DECEMBER - SUN 19 JANUARY By E R Braithwaite Adapted by Ayub Khan-Din Starring MATTHEW KELLY and ANSU KABIA Follow us on @WolvesGrand Like us on Facebook: Wolverhampton Grand Box Office 01902 42 92 12 BOOK ONLINE AT www.grandtheatre.co.uk Contents -

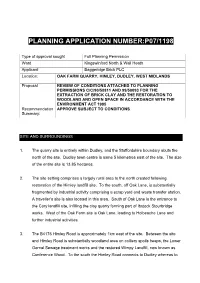

Planning Application Number:P07/1198

PLANNING APPLICATION NUMBER:P07/1198 Type of approval sought Full Planning Permission Ward Kingswinford North & Wall Heath Applicant Baggeridge Brick PLC Location: OAK FARM QUARRY, HIMLEY, DUDLEY, WEST MIDLANDS Proposal REVIEW OF CONDITIONS ATTACHED TO PLANNING PERMISSIONS C/C/90/50811 AND 99/50093 FOR THE EXTRACTION OF BRICK CLAY AND THE RESTORATION TO WOODLAND AND OPEN SPACE IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE ENVIRONMENT ACT 1995 Recommendation APPROVE SUBJECT TO CONDITIONS Summary: SITE AND SURROUNDINGS 1. The quarry site is entirely within Dudley, and the Staffordshire boundary abuts the north of the site. Dudley town centre is some 5 kilometres east of the site. The size of the entire site is 13.85 hectares. 2. The site setting comprises a largely rural area to the north created following restoration of the Himley landfill site. To the south, off Oak Lane, is substantially fragmented by industrial activity comprising a scrap yard and waste transfer station. A traveller’s site is also located in this area. South of Oak Lane is the entrance to the Cory landfill site, infilling the clay quarry forming part of Ibstock Stourbridge works. West of the Oak Farm site is Oak Lane, leading to Holbeache Lane and further industrial activities. 3. The B4176 Himley Road is approximately 1km east of the site. Between the site and Himley Road is substantially woodland area on colliery spoils heaps, the Lower Gornal Sewage treatment works and the restored Wimpy Landfill, now known as Conference Wood. To the south the Himley Road connects to Dudley whereas to the north it extends to the A449 trunk road. -

Shropshire Cover Online.Qxp Cover 25/06/2015 10:35 Page 1 the MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE

Shropshire Cover Online.qxp_cover 25/06/2015 10:35 Page 1 THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE SHROPSHIRE ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 355 JULY 2015 MARCUS BRIGSTOCKE PLAYS LICHFIELD FESTIVAL THE BIG ART SHOW the biggest event of its kind... DARREN EMERSON Underground DJ at The Buttermarket INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE. LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS EVENTS FOOD & DRINK & MUCH MORE! ALANTALKS SHREWSBURY SURTEES FOLK INTERVIEW INSIDE... Wolverhampton Speedway (FP- July 15).qxp_Layout 1 22/06/2015 16:37 Page 1 Contents July Region 2.qxp_Layout 1 22/06/2015 20:40 Page 1 July 2015 Editor: INSIDE: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 Editorial Assistants: Dirty Rotten Brian O’Faolain Scoundrels [email protected] 01743 281701 West End musical Lauren Foster arrives in Stoke p21 [email protected] 01743 281707 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Jamie Ryan [email protected] 01743 281720 Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 Subscriptions: Adrian Parker [email protected] Marcus Brigstocke 01743 281714 intelligent comedy at Managing Director: Lichfield Festival Paul Oliver p18 [email protected] 01743 281711 Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan [email protected] 01743 281710 Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell From EastEnders to East Is East. Interview with Pauline McLynn, page 6. Chris Atherton Accounts Administrator Julia Perry [email protected] TO GET THE VERY 01743 281717 News p4 Contributors: LATEST LISTING Graham Bostock: Theatre INFORMATION, James Cameron-Wilson: Music p11 Film; Eva Easthope, VISIT: Jessica Aston, Patsy whatsonlive.co.uk p18 Robert Plant Moss, Jack Rolfe, Jan Comedy plays Cannock Chase Watts, Simon Carter INCLUDING p14 Head Office: BOOKING ONLINE 13-14 Abbey Foregate, Theatre p21 Shrewsbury, SY2 6AE The Midlands’ most Tel: 01743 281777 comprehensive p35 e-mail: [email protected] entertainment website Film/DVD Follow us on.. -

Crooked House Viewpo

Viewpoint Sinking a pint © Rory Walsh Time: 15 mins Region: West Midlands Landscape: urban Location: The Crooked House (The Glynne Arms), Coppice Mill, Himley Road, Himley, South Staffordshire DY3 4DA Grid reference: SO 89753 90815 Keep an eye out for: The ‘marble trick’ – ask the bar staff for a demonstration... With its wonky windows, droopy doors and a bar that looks like the regulars need to prop it up, The Crooked House is one of Britain’s quirkiest pubs. Spill your pint in here and it seems to pour uphill. If the walls look straight, it’s time to go home! In the 1940s the building was almost demolished but today it attracts people from around the world. The pub’s eye-boggling optical illusions inside and out have made it a unique landmark. Why is this Black Country pub so crooked? Built in 1765 as a farmhouse, this building became a pub in the 19th century when it opened as The Siden Arms. ‘Siden’ is a local dialect word for ‘crooked’ or ‘lopsided’ - a name that shows this building was leaning well over 100 years ago! Though now called The Crooked House many regulars recall its previous name, The Glynne Arms. Sir Stephen Glynne was a 19th century landowner and the building was on his estate. What his land contained makes the pub crooked. Like much of the area west of Birmingham, the village of Himley sits above vast amounts of coal, iron ore, limestone, clay and sand. From the 1800s these natural resources were mined and used in industrial manufacturing. -

Coming Alive With

Midlands Cover - Oct LW_Layout 1 23/09/2013 15:00 Page 1 MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS THE MIDLANDS ESSENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE ISSUE 334 OCTOBER 2013 OCTOBER www.whatsonlive.co.uk £1.80 ISSUE 334 OCTOBER 2013 DAVID TENNANT RETURNS TO THE REGION INSIDE: Michael Morpurgo talks about backing a winner... interview inside Diane Keen on her return to the stage interview inside THE DEFINITIVE LISTINGS GUIDE INCLUDING coming Alive with BIRMINGHAM WOLVERHAMPTON WALSALL DUDLEY COVENTRY PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART STRATFORD WORCESTER REDDITCH MALVERN SHREWSBURY TELFORD STAFFORD STOKE What’sOn MAGAZINE GROUP interview inside... ISSN 2053 - 3128 - 2053 ISSN grand_whatson FP Oct_Layout 1 23/09/2013 16:31 Page 1 Great Theatre at the Grand! MON 30 SEPTEMBER - SAT 5 OCTOBER TUES 8 - SAT 12 OCTOBER TUES 15 - SAT 19 OCTOBER South StaffS MuSical theatre coMpany proudly preSentS the rodgerS and haMMerStein claSSic “Some excellent singing and acting performances” Express & Star Guys and Dolls 2011 “A cast of 40 hit the peaks of performance” Birmingham Mail The Sound of Music 2012 An amateur production Directed and Choreographed by CRAIG REVEL HORWOOD WITH DANIEL HILL ROBIN SEBASTIAN DIRECTED BY ROY MARSDEN TUES 22 - SAT 26 OCTOBER MON 28 OCTOBER - SAT 2 NOVEMBER TUES 5 - SAT 9 NOVEMBER By E R Braithwaite Adapted by Ayub Khan-Din Starring The favourite musical set in the depths of the 1930s sees Annie, a fiery young orphan girl, MATTHEW seeking escape from her life in a miserable KELLY orphanage run by the tyrannical Miss Hannigan. -

Kingswinford (2Nd Edition)

HITCHMOUGH’S BLACK COUNTRY PUBS KINGSWINFORD (INC. HIMLEY, WALL HEATH) 2nd. Edition - © 2010 Tony Hitchmough. All Rights Reserved www.longpull.co.uk ALBION High Street, KINGSWINFORD OWNERS LICENSEES William Timmins [1872] NOTES Stourbridge Observer 27/6/1874 “A well attended meeting of colliers connected with the Shut End Colliery, was held on Thursday afternoon, at the ALBION INN, Kingswinford, and after a long discussion, it was unanimously resolved ‘to remain out, and not to follow the example of the few who had returned at the drop’.” ALBION 382, Albion Street, WALL HEATH OWNERS Elizabeth Munday [1886] Alfred Albert Kinsey J. P. Simpkiss (acquired in April 1955) Greenall Whitley [1994] LICENSEES John Munday [1864] – 1878); Mrs. Elizabeth Munday (1878 – 1881); Joseph Bate (1881 – 1884); Enoch Bennett (1884 – 1894); Matthew Bartlett (1894 – 1898); Sarah Bartlett (1898 – 1901); Eli Bird (1901 – 1918); Mary Bird (1918 – 1919); Alfred Albert Kinsey (1919 – 1920); Walter Alt Kinsey (1920 – 1932); Florence Annie Kinsey (1932 – 1935); Alfred Alt Kinsey (1935 – [1938] Walter Kinsey [1940] William Ball (1954 – [ ] George T Scarratt (1967 – 1975) Barrie Hickman [1994] Duncan Edmonds [2007] 2000 NOTES It closed at 10pm. John Munday was also a tailor. [1864], [1870], [1872], [1873] It was put up for auction in October 1900. - “freehold, full licenced” Eli Bird was also a builder. [1912] George T. Scarratt died in 1975. [2010] 2009 BELL Bell Street, KINGSWINFORD OWNERS LICENSEES William Fennell [1850] BELL 614, High Street, KINGSWINFORD OWNERS Mark Rollinson, Brierley Hill (acquired c.1894) leased by William Henry Simpkiss leased by North Worcestershire Breweries Ltd (c. 1896) Arthur Thomas Allen J. -

You Have Mail – on Market Delivered Directly to Your Inbox

You have mail – On market delivered directly to your inbox As we enter 2008, it only seems like From January 2008, using the yesterday that we were talking about information you have given us about the new millennium - life really does you and your business, we will now move on at pace! cluster information together under one banner and send you a tailored In 2007 Fleurets unveiled a new image; electronic On market. This new a revitalised working practice and a service will contain information about new ‘Fresh Approach’ to doing a whole host of properties, but most business. We’ve enjoyed the last year importantly, it will have a bias towards and we hope it’s been a prosperous the information you need. one for you. To make this evolution a successful 2008 will see further changes take one, we might need a little help from place here at Fleurets. One such you in the early days. When you change will be the way we deliver receive your first issue, please let us information about properties to you have your feedback via your local and in particular, our On market, Fleurets office - tell us if you need Hotel review and Restaurant review more, or different information and publications. we’ll do our very best to oblige. Each month thousands of copies of So it’s an end to a printed product, each are printed and posted out in the something those close to the hope that you will find their contents of environmental issues we face will interest. Well, we believe it’s time we appreciate and hello to the dawn of a went one better. -

Getting Married in STAFFORDSHIRE 2018 Staffordshire REGISTRATION SERVICE

Getting Married IN STAFFORDSHIRE 2018 Staffordshire REGISTRATION SERVICE aim to make your day as individual as the union it celebrates We have included a sample of comments from couples whose ceremonies we have conducted in 2017 “We really could not have asked for a day that was more perfect in every way.” “The friendly, welcoming staff made me feel calm and were so lovely to my children.” “The staff kept everyone calm and made our day so special, it made such a difference to us both.” “I felt like a princess, County Buildings looked enchanting with silver bows and sparkling lights, such precious memories.” “Everyone commented on how lovely and personalised the ceremony was.” “My father came out of hospital to give me away, the staff were so lovely to him, he said it was his proudest moment.” “Even though this was an everyday job for the Registrar we were made to feel special.” CONTENTS 4 Staffordshire Registration Service 5 The Ceremony 6 Civil Partnerships 7 Same Sex Marriage 8 Giving Notice 10 Weddings Abroad And Changes To Your Passport 11 Renewal Of Marriage Vows 12 Re-Registration & Naming Ceremonies 13 The Marriage Fees 14 County Buildings 18 Outdoor Venues 20 Registration Offices Staffordshire REGISTRATION SERVICE Inside this guide you will find information on a wide range of wedding services and venues, to help to make your wedding day the most unique and memorable day of your life. Before booking your chosen venue, you will need to book your ceremony. Our staff will help to tailor the ceremony to your requirements.