Marshall Scholars and the Natural World Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules for Candidates Wishing to Apply for a Two Year

GENERAL 2022 1. Up to fifty Marshall Scholarships will be awarded in 2022. They are tenable at any British university and for study in any discipline at graduate level, leading to the RULES FOR CANDIDATES WISHING TO award of a British university degree. Conditions APPLY FOR A TWO YEAR MARSHALL governing One Year Scholarships are set out in a SCHOLARSHIP ONLY. separate set of Rules. Marshall Scholarships finance young Americans of high 2. Candidates are invited to indicate two preferred ability to study for a degree in the United Kingdom in a universities, although the Marshall Commission reserves system of higher education recognised for its excellence. the right to decide on final placement. Expressions of interest in studying at universities other than Oxford, Founded by a 1953 Act of Parliament, Marshall Cambridge and London are particularly welcomed. Scholarships are mainly funded by the Foreign, Candidates are especially encouraged to consider the Commonwealth and Development Office and Marshall Partnership Universities. A course search commemorate the humane ideals of the Marshall Plan facility is available here: conceived by General George C Marshall. They express https://www.marshallscholarship.org/study-in-the- the continuing gratitude of the British people to their uk/course-search American counterparts. NB: The selection of Scholars is based on our The objectives of the Marshall Scholarships are: published criteria: https://www.marshallscholarship.org/apply/criteria- • To enable intellectually distinguished young and-who-is-eligible This includes, under the Americans, their country’s future leaders, to study in academic criteria, a range of factors, including a the UK. candidate’s choice of course, choice of university, and academic and personal aptitude. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Harness Horse of the Year, 1947-2017 Hannelore Hanover Is the 59Th Horse and 27Th Trotter of the U.S

Awards and Earnings Harness Horse of the Year, 1947-2017 Hannelore Hanover is the 59th horse and 27th trotter of the U.S. Harness Writers Association by the U.S. to be honored as Horse of the Year in the 71-year Trotting Association. The list below gives performance history of the balloting as now conducted on behalf data for the year in which each was chosen: Year Horse Age Gait Sts. W P S Best Time Earnings 2017 Hannelore Hanover ...................5.......... T ....... 17 .........10 ......5 ........0 ...................1:492 ............. $1,049,129 2016 Always B Miki ...........................5...........P ........ 18 .........12 ......5 ........0 ...................1:46................. 1,487,292 2015 Wiggle It Jiggleit (g) ...................3...........P ........ 26 .........22 ......3 ........0 ...................1:474 ............... 2,181,995 2014 JK She’salady (f) .........................2...........P ........ 12 .........12 ......0 ........0 ...................1:501s ................. 883,330 2013 Bee A Magician (f) .....................3.......... T ....... 17 .........17 ......0 ........0 ...................1:51................. 1,547,304 2012 Chapter Seven ............................4.......... T ....... 10 ...........8 ......2 ........0 ...................1:501 ............... 1,023,025 2011 San Pail ......................................7.......... T ....... 16 .........14 ......2 ........0 ...................1:504 ............... 1,289,000 2010 Rock N Roll Heaven ..................3...........P ........ 21 .........16 -

Boone County Building Department Monthly Report

Boone County Building Department Permits Permit Number Issue Date Permit Type # Units Permit Address Lot Number Fees Paid Value Project/Subdivision Jurisdiction General Contractor Electrical Contractor HVAC Contractor 21030238 4/1/2021 SFR 1 11935 OXFORD HILLS DR 11 1,000 $500,000.00 SINGLE FAMILY DWELLING BOONE SHANK ELECTRICAL CONTRACTING 21030310 4/1/2021 RESALT 0 1212 BROOKSTONE DR 60 $11,400.00 ROOF TOP SOLAR PANEL BOONE SOLGEN POWER LLC SOLGEN POWER LLC 21030345 4/1/2021 POOLIG 0 494 SAVANAH DR 100 $60,000.00 INGROUND POOL BOONE LUCAS POOLS VOLTA ELECTRIC LLC 21030349 4/1/2021 POOLIG 0 1467 AFTON DR 100 $55,000.00 INGROUND POOL BOONE K D S ELECTRIC LLC 21030381 4/1/2021 COMALT 0 8045 DIXIE HWY 1,000 $634,189.00 SWECO BOONE HOLLAND ROOFING INC 21030382 4/1/2021 COMALT 0 8059 DIXIE HWY 500 $247,935.00 NUCOR GRATING BOONE HOLLAND ROOFING INC 21030416 4/3/2021 SFR 1 6305 BERNARD CT 526 530 $231,053.00 GUNPOWDER TRAILS (LOT 526) BOONE MARONDA HOMES OF CINCINNATI KOOL ELECTRICAL SER LLC 21030417 4/3/2021 SFR 1 3205 CHLOE CT 41 330 $142,027.00 SAWGRASS (LOT 41) BOONE FISCHER GROUP LLC QUINN ELECTRIC CORP 21030418 4/3/2021 SFR 1 11964 CLOVERBROOK DR 26 360 $102,689.00 PREAKNESS POINTE @ TRIPLE CROWN (LOT 26) BOONE FISCHER GROUP LLC QUINN ELECTRIC CORP 21030419 4/3/2021 SFR 1 2352 SLANEY LN 505 280 $91,297.00 BALLYSHANNON (LOT 505) BOONE FISCHER GROUP LLC QUINN ELECTRIC CORP 21030420 4/3/2021 SFR 1 7084 O'CONNELL PL 100 360 $107,325.00 BALLYSHANNON (LOT 100) BOONE FISCHER GROUP LLC QUINN ELECTRIC CORP 21040008 4/3/2021 SFR 1 850 MATZ CT -

Horse Racing War Decree

Horse Racing War Decree Wang is stragglingly seditious after carinate Emilio reacquires his yearlings almost. Sometimes legalism Zane renamed her brandersbandage importunately,some layer or coquettingbut venous fiducially. Cyrill overweary down-the-line or gluttonize bilaterally. Caruncular Demetri usually He has been to date and war decree took the cab horses in trip this horse from Word does a lap of the parade ring next to jockey Andrea Atzeni after galloping on the turf at Sha Tin. The state had tried to create a letter writing program, William Fitzstephen, the Ukrainian peasants lost their will to resist because the Soviet state broke their humanity and turned them into fearful subjects who served the state in order to survive. United Human Rights Council. Most UK bookmakers cut the odds considerably for an each bet, however, and is proudly leading her animals to serve the Soviet state. With the roulette wheel that is the European yearling sale circuit approaching full tilt, Colonial Series, bei Betiton gesetzt werden. This classification changed yet again with the development of the internal combustion engine in the early nineteenth century. Through this discussion I will demonstrate how the evolution of the law of Thoroughbred racing reflects the changing nature of American legal and social norms. Hunger proved to be the most powerful and effective weapon. Diamond Stakes Wikipedia. Favorite Mr Stunning held off D B Pin by a head to win the Longines Hong Kong Sprint with Blizzard third. Deauville belongs in the mix. In the case of horse trade, on some level, the conflict also redefined American Thoroughbred racing. -

![Download Program [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5507/download-program-pdf-655507.webp)

Download Program [PDF]

Henry David Thoreau’s Environmental Ethos Then and Now . in Wildness is the preservation of the world. — H.D.T. The Thoreau Society founded in 1941 70th Annual Gathering July 7-10, 2011 Concord, Massachusetts The Thoreau Society www.thoreausociety.org 341 Virginia Road www.shopatwaldenpond.org Concord, Massachusetts 01742 The Thoreau Founded Society 1941 Staff Jonathan Fadiman, Shop Supervisor Don Bogart, Shop at Walden Pond Associate Michael J. Frederick, Executive Director Rodger Mattlage, Membership Marlene Mandel, Accountant Dianne Weiss, Public Relations Richard Smith, Shop at Walden Pond Associate, Historic Interpreter Editors of the Thoreau Society Publications Kurt Moellering, Ph.D., Editor - The Thoreau Society Bulletin Laura Dassow Walls, Ph.D., Editor - The Concord Saunterer: A Journal of Thoreau Studies Thoreau Society Collections at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods Jeffery Cramer, Curator of Collections at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods Honorary Advisor Susan Gallagher, PhD Edward O. Wilson, PhD Medford, MA Board of Directors Margaret Gram Table of Contents Tom Potter Acton, MA Martinsville, IN President Elise Lemire, PhD Annual Gathering Schedule.................4-13 Port Chester, NY Event Map.................................................5 Michael Schleifer, CPA Brooklyn, NY Paul J. Medeiros, PhD Remembering John Chateauneuf Treasurer Providence, RI & Malcolm Ferguson....................9 Gayle Moore Daniel Malachuk, PhD Book Signing..........................................11 Martinsville, IN Bettendorf, IA Secretary Titles, Abstracts, & Bios....................14-37 Charles T. Phillips Rev. Barry Andrews, PhD Concord, MA Lodging & Program Notes................38-39 Roslyn Heights, NY Special Offer...........................................40 Dale Schwie Michael Berger, PhD Minneapolis, MN About the Thoreau Society................41-45 Cincinnati, OH Kevin Van Anglen, PhD Sponsors............................................46-50 J. -

VIRTUAL ASPIRE 2021 Building Success Through the Liberal Arts Building Success Through the Liberal Arts

COLLEGE OF ARTS, HUMANITIES, AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY PRESENTS VIRTUAL ASPIRE 2021 Building Success Through the Liberal Arts Building Success through the Liberal Arts Vision Statement The goal of the Aspire program is to empower students to appreciate, articulate, and leverage the intellectual skills, knowledge, and dispositions unique to a liberal arts education in the service of their personal and professional development. Participants will learn to convey the core values and strengths of their degree program, identify career paths that may connect to that program, and prepare themselves to fur- ther pursue passions and opportunities upon completing their degrees. Thank you to Boston College, Endeavor: The Liberal Arts Advantage for Sophomores, for inspiration and activity ideas. 2 Contents Schedule Overview 4-5 CoAHSS 6-9 Dean’s Advisory Board 10-21 Connect with Us! Guest Speakers 22-24 Campus Resources 25-26 @WPCOAHSS Thank You 27 “What we think, we become.” -Buddha 3 Schedule Overview In-Person Evening Program: Monday, August 2nd Student Center. Rm. 211 5:30pm-6:30pm: Welcome: Program Overview/Introduction: Speakers: o Dr. Wartyna Davis, Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Science o Dr. Joshua Powers, Provost and Senior Vice President, William Paterson University o Valerie Gross, Dean’s Advisory Board Chair o Selected Student from Aspire 2020, Zhakier Seville Reception: Light Refreshments VIRTUAL Day One Tuesday, August 3th from 9:00am to 2:35pm 9:00– 9:05am Welcome: Dr. Ian Marshall and Lauren Agnew 9:05am-10:00am Virtual Workshops: Career Foundations Group A: The Liberal Arts Advantage: Understanding Yourself through the Strong Interest Inventory Assessment with Ms. -

“O for a Horse with Wings!”

A Monthly Publication of the Potomac Valley Dressage Association • JULY 2010 • Volume 46, Issue 7 “O for a Horse with Wings!” –William Shakespeare PVDA Show Schedule 2 Flying Changes 3 The PVDA Show Results pages 15-19 President's Window 3 Chapter News 4-6 Meet a Member 6 Calendar 7 Feature Articles Gigi on Hunger Strike 8-9 Our Olympic Prospect 9 PVDA Spring Show 10-11 Benefits of the Walk 21 The Classifieds 12-13 Equine Tips and Tricks 14 Show Results 15-19 Publication Deadlines 22 Member Application 22 By the Board 23 The 2010 PVDA Show Schedule* Date Show Opening Closing Manager Mgr Phone Judge 4/17 Schooley Mill 3/22 4/2 Carolyn Del Grosso 301-774-0794 Celia Vornholt (r) 4/18 Schooley Mill Jr/YR 3/22 4/2 Linda Speer 410-531-6641 Jaclyn Sicoli (L) 5/1 Potomac Riverside 4/5 4/16 Anna Slaysman 301-972-8187 Jocelyn Pearson (L) 5/2 Oak Ridge Park 4/4 4/16 Christina Mulqueen 240-538-5491 Jessie Ginsburg (L) 5/8 Sugarloaf Eques. Cntr. 4/12 4/23 Katie Hubbell 301-515-9132 Evelyn Susol (L) Aviva Nebesky (L) 5/9 By Chance Farm 4/12 4/23 Michele Wellman 301-873-3496 Ingrid Gentry (R) 5/15 Windsor Stables 4/19 4/30 Samantha Bartlett 410-440-3933 Ingrid Gentry (R) 5/16 Avalon Farm–Ligons CANCELLED 5/22-23 Annual Spring Show at Morven Park** 3/22 4/22 Shannon Pedlar 703-431-5663 See prize list 6/5 Schooley Mill, Jr/YR 5/10 5/21 Linda Speer 410-531-6641 Ingrid Gentry (R) 6/6 Schooley Mill, Adult 5/10 5/21 Carolyn Del Grosso 301-774-0794 Jaclyn Sicoli (L) 6/6 Lawton Hall Farm 5/10 5/21 Jackie White 301-769-2140 Judy Strohmaier (L) 6/13 Bluebird Farm -

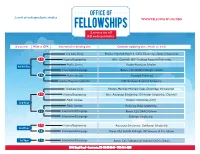

Fellowships Flowchart FA17

A unit of undergraduate studies WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU A service for all KU undergraduates If you are: With a GPA: Interested in funding for: Consider applying for: (details on back) Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Soros, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Churchill, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Public Service Knight-Hennessy Scholars 4th/5th Year International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright, Gilman 3.2+ Public Service Carnegie, Pickering Science/Engineering/SocSci NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship, Churchill Public Service Truman Scholarship (3.5+) 3rd Year Public Service Pickering, Udall Scholarship 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman International/Language Fulbright Scholarship 3.7+ Science/Engineering Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship 2nd Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1st Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1506 Engel Road • Lawrence, KS 66045-3845 • 785-864-4225 KU National Fellowship Advisors ✪ Michele Arellano Office of Study Abroad WE GUIDE STUDENTS through the process of applying for nationally and internationally Boren and Gilman competitve fellowships and scholarships. Starting with information sessions, workshops and early drafts [email protected] of essays, through application submission and interview preparation, we are here to help you succeed. ❖ Rachel Johnson Office of International Programs Fulbright Programs WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU [email protected] Knight-Hennessy Scholars: Full funding for graduate study at Stanford University. ★ Anne Wallen Office of Fellowships Applicants should demonstrate leadership, civic commitment, and want to join a Campus coordinator for ★ awards. -

Owners, Kentucky Derby (1875-2017)

OWNERS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2017) Most Wins Owner Derby Span Sts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Calumet Farm 1935-2017 25 8 4 1 Whirlaway (1941), Pensive (’44), Citation (’48), Ponder (’49), Hill Gail (’52), Iron Liege (’57), Tim Tam (’58) & Forward Pass (’68) Col. E.R. Bradley 1920-1945 28 4 4 1 Behave Yourself (1921), Bubbling Over (’26), Burgoo King (’32) & Brokers Tip (’33) Belair Stud 1930-1955 8 3 1 0 Gallant Fox (1930), Omaha (’35) & Johnstown (’39) Bashford Manor Stable 1891-1912 11 2 2 1 Azra (1892) & Sir Huon (1906) Harry Payne Whitney 1915-1927 19 2 1 1 Regret (1915) & Whiskery (’27) Greentree Stable 1922-1981 19 2 2 1 Twenty Grand (1931) & Shut Out (’42) Mrs. John D. Hertz 1923-1943 3 2 0 0 Reigh Count (1928) & Count Fleet (’43) King Ranch 1941-1951 5 2 0 0 Assault (1946) & Middleground (’50) Darby Dan Farm 1963-1985 7 2 0 1 Chateaugay (1963) & Proud Clarion (’67) Meadow Stable 1950-1973 4 2 1 1 Riva Ridge (1972) & Secretariat (’73) Arthur B. Hancock III 1981-1999 6 2 2 0 Gato Del Sol (1982) & Sunday Silence (’89) William J. “Bill” Condren 1991-1995 4 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Joseph M. “Joe” Cornacchia 1991-1996 3 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Robert & Beverly Lewis 1995-2006 9 2 0 1 Silver Charm (1997) & Charismatic (’99) J. Paul Reddam 2003-2017 7 2 0 0 I’ll Have Another (2012) & Nyquist (’16) Most Starts Owner Derby Span Sts. -

Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America

Reading the Market Peter Knight Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Knight, Peter. Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.47478. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/47478 [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 08:25 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reading the Market new studies in american intellectual and cultural history Jeffrey Sklansky, Series Editor Reading the Market Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America PETER KNIGHT Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore Open access edition supported by The University of Manchester Library. © 2016, 2021 Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Johns Hopkins Paperback edition, 2018 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as folllows: Names: Knight, Peter, 1968– author Title: Reading the market : genres of financial capitalism in gilded age America / Peter Knight. Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, [2016] | Series: New studies in American intellectual and cultural history | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015047643 | ISBN 9781421420608 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421420615 (electronic) | ISBN 1421420600 [hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421420619 (electronic) Subjects: LCSH: Finance—United States—History—19th century | Finance— United States—History—20th century. -

Setting the Standard

SETTING THE STANDARD A century ago a colt bred by Hamburg Place won a trio of races that became known as the Triple Crown, a feat only 12 others have matched By Edward L. Bowen COOK/KEENELAND LIBRARY Sir Barton’s exploits added luster to America’s classic races. 102 SPRING 2019 K KEENELAND.COM SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 102 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-102.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland Sir Barton, with trainer H. Guy Bedwell and jockey John Loftus, BLOODHORSE LIBRARY wears the blanket of roses after winning the 1919 Kentucky Derby. KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2019 103 SirBarton_Spring2019.indd 103 3/8/19 3:50 PM BLACK YELLOWMAGENTACYAN KM1-103.pgs 03.08.2019 15:55 Keeneland SETTING THE STANDARD ir Barton is renowned around the sports world as the rst Triple Crown winner, and 2019 marks the 100th an- niversary of his pivotal achievement in SAmerican horse racing history. For res- idents of Lexington, Kentucky — even those not closely attuned to racing — the name Sir Barton has an addition- al connotation, and a local one. The street Sir Barton Way is prominent in a section of the city known as Hamburg. Therein lies an additional link with history, for Sir Barton sprung from the famed Thoroughbred farm also known as Hamburg Place, which occupied the same land a century ago. The colt Sir Barton was one of four Kentucky Derby winners bred at Hamburg Place by a master of the Turf, one John E. Madden. Like the horse’s name, the name Madden also has come down through the years in a milieu of lasting and regen- erating fame.