Building a Winning NFL Roster: Best Practices for Sustained Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Houston Texans – 9/1

— KEY TRANSACTIONS — 2019: (HOUSTON TEXANS – 9/1, 2/0) Re-Signed a Reserve/Future contract with Baltimore on Played in nine regular season games (one start) and both 1/29/21 postseason contests primarily on special teams and as a Signed to the Ravens' practice squad on 1/12/21 reserve offensive lineman…Houston’s offense ranked No. 9 Released by Houston on 1/7/21 in rushing (125.6 ypg) and eighth in third-down conversion percentage (43.5%) Activated from the practice squad (standard elevation) on 11/7/20, 11/14/20, 11/21/20 and (COVID-19 replacement) on Contributed on special teams in the Divisional Round at KC 1/2/21 (1/12/20) Signed to the Texans' practice squad on 9/7/20 Saw one snap on offense and three on special teams in the Wild Card win vs. Buf. (1/4/20) Released with the Texans on 9/5/20 Saw 46 offensive snaps at center vs. Ten. (12/29)…Helped Signed a contract extension with Houston on 8/30/18 block for an offense that netted 301 yards Signed with the Texans as an undrafted rookie free agent on Rotated in at RG (14 snaps) and contributed on special teams 5/8/15 at TB (12/21) — CAREER HIGHLIGHTS — Saw 30 snaps on offense vs. Den. (12/8)…Helped block for Has seen action in 58 games (28 starts) in six seasons with an offense that netted 414 yards and averaged 6.1 yards-per- the Texans (2015-20)…Also appeared in five playoff contests carry (two starts) with Houston over that span Made his first start of the season at RG and played in all 67 — PERSONAL — offensive snaps vs. -

Denver Broncos (4-9) at Indianapolis Colts (3-10)

Week 15 Denver Broncos (4-9) at Indianapolis Colts (3-10) Thursday, December 14, 2017 | 8:25 PM ET | Lucas Oil Stadium | Referee: Terry McAulay REGULAR-SEASON SERIES HISTORY LEADER: Broncos lead all-time series, 13-10 LAST GAME: 9/18/16: Colts 20 at Broncos 34 STREAKS: Broncos have won 2 of past 3 LAST GAME AT SITE: 11/8/15: Colts 27, Broncos 24 DENVER BRONCOS p INDIANAPOLIS COLTS LAST WEEK W 23-0 vs. New York Jets LAST WEEK L 13-7 (OT) at Buffalo COACH VS. OPP. Vance Joseph: 0-0 COACH VS. OPP. Chuck Pagano: 2-2 PTS. FOR/AGAINST 17.6/24.2 PTS. FOR/AGAINST 16.3/26.4 OFFENSE 312.1 OFFENSE 290.7 PASSING Trevor Siemian: 201-340-2218-12-13-74.4 PASSING Jacoby Brissett: 228-381-2611-11-7-82.5 RUSHING C.J. Anderson: 181-700-3.9-2 RUSHING Frank Gore: 210-762-3.6-3 RECEIVING Demaryius Thomas: 68-771-11.3-4 RECEIVING Jack Doyle (TE): 64-564-8.8-3 DEFENSE 280.5 (1L) DEFENSE 375.3 SACKS Von Miller: 10 SACKS Jabaal Sheard: 4.5 INTs Many tied: 2 INTs Rashaan Melvin: 3 TAKE/GIVE -14 (13/27) TAKE/GIVE +3 (18/15) PUNTING (NET) Riley Dixon: 46.0 (39.7) PUNTING (NET) Rigoberto Sanchez (R): 45.1 (42.5) KICKING Brandon McManus: 85 (22/22 PAT; 21/28 FG) KICKING Adam Vinatieri: 84 (18/20 PAT; 22/25 FG) BRONCOS NOTES COLTS NOTES • QB TREVOR SIEMIAN has 90+ rating in 2 of past 3. -

Montana Ready for Quick Cal Poly

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 11-6-1969 Montana ready for quick Cal Poly University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "Montana ready for quick Cal Poly" (1969). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 5289. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/5289 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONTANA READY FOR QUICK CAL POLY brunell/js 11/6/69 sports sports one 6 football MISSOULA-— Information Services • University of montana • missoula, montana 59801 *(406) 243-2522 ► The big question Saturday for Jack Swarthout's 8-0 Grizzlies is how the team can handle the small but quick Cal Poly offensive line. The Montana rush defense will get a real test in containing quickness and speed.of the ' Mustangs. nWe must contain the running of Joe Acosta and quarterback Gary Abata," Swarthout said. "Our boys are going out there and prove they are a much better team than the Bozeman showing," the UM mentor said. "We can see the end now and we want it to be just as we planned it, Swarthout said. -

Cornerback André Goodman

Patrick Smyth, Executive Director of Media Relations ([email protected] / 303-264-5536) Rebecca Villanueva, Media Services Manager ([email protected] / 303-264-5598) Erich Schubert, Media Relations Coordinator ([email protected] / 303-264-5503) DENVER BRONCOS QUOTES (10/11/11) CORNERBACK ANDRÉ GOODMAN On the quarterback switch “At the end of the day, I think we’re all disappointed for [QB] Kyle [Orton] because it almost implicates him in a way, that the reason we’re 1-4 is it’s his fault. That’s not the case. It could have been me. It could have been anybody on this team. None of us are doing a good enough job to make plays and help us win. As disappointed as you are for Kyle, you’re kind of excited for [QB Tim] Tebow because he’s getting a chance. We’re just hoping that translates into wins. “At the end of the day we’re 1-4 and that’s the reason why we’re not cheering. We’re 1-4 and we haven’t been playing good football. So there is no reason for this locker room to be excited at the end of the day. We have a long way to go to get ourselves close to being competitive and we’re not there. That’s the reason the locker room is kind of subdued. And again, the headline is probably Kyle and it could’ve been any of us, but the fact of the matter is that it’s Tim Tebow and he has such an aura about him and a following that’s such a big story.” On quarterback being the most important position on the team “It is but the guys around him can help him play better whether it’s the guys on his side of the ball or the guys on the defensive side of the ball. -

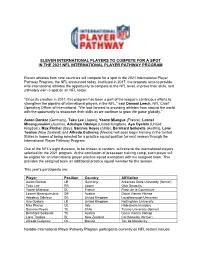

Eleven International Players to Compete for a Spot in the 2021 Nfl International Player Pathway Program

ELEVEN INTERNATIONAL PLAYERS TO COMPETE FOR A SPOT IN THE 2021 NFL INTERNATIONAL PLAYER PATHWAY PROGRAM Eleven athletes from nine countries will compete for a spot in the 2021 International Player Pathway Program, the NFL announced today. Instituted in 2017, the program aims to provide elite international athletes the opportunity to compete at the NFL level, improve their skills, and ultimately earn a spot on an NFL roster. “Since its creation in 2017, this program has been a part of the league’s continuous efforts to strengthen the pipeline of international players in the NFL,” said Damani Leech, NFL Chief Operating Officer of International. “We look forward to providing athletes from around the world with the opportunity to showcase their skills as we continue to grow the game globally.” Aaron Donkor (Germany), Taku Lee (Japan), Yoann Miangue (France), Leonel Misangumukini (Austria), Adedayo Odeleye (United Kingdom), Ayo Oyelola (United Kingdom), Max Pircher (Italy), Sammis Reyes (Chile), Bernhard Seikovits (Austria), Lone Toailoa (New Zealand) and Alfredo Gutierrez (Mexico) will soon begin training in the United States in hopes of being selected for a practice squad position for next season through the International Player Pathway Program. One of the NFL's eight divisions, to be chosen at random, will receive the international players selected for the 2021 program. At the conclusion of preseason training camp, each player will be eligible for an international player practice squad exemption with his assigned team. This provides the -

Good Signs, Bad Signs

C M Y K D7 DAILY 10-28-07 MD BD D7 CMYK The Washington Post x B Sunday, October 28, 2007 D7 RedskinsGameday By Gene Wang 1 REDSKINS (4-2) VS. PATRIOTS (7-0) 4:15 P.M. AT GILLETTE STADIUM » TV: WTTG-5, WBFF-45 » RADIO: WWXX (92.7 FM), WWXT (94.3 FM), WBIG (100.3 FM), WXTR (730 AM) » LINE: Patriots by 16 ⁄2 REDSKINS ROSTER FIRST DOWN SECOND DOWN THIRD DOWN FOURTH DOWN PATRIOTS ROSTER No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. Ball Control Rough Up Randy Pressure Brady Crowd Control No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. 4 Derrick Frost P 6-4 208 The Patriots have perhaps the NFL’s Wide receiver Randy Moss is in the Patriots quarterback Tom Brady has The fans at Gillette Stadium are going 3 Stephen Gostkowski PK 6-1 210 6 Shaun Suisham PK 6-0 205 best passing attack, so it will be midst of a career resurgence since thrown 27 touchdown passes and two to be charged up to see their team at 6 Chris Hanson P 6-2 202 8 Mark Brunell QB 6-1 217 important for the Redskins to win time joining the Patriots in the offseason. interceptions thanks to plenty of time home for the first time in three weeks. 7 Matt Gutierrez QB 6-4 230 15 Todd Collins QB 6-4 228 of possession and keep New England’s Moss has caught passes in double- in the pocket. Brady has been sacked The Patriots played their past two 10 Jabar Gaffney WR 6-1 200 17 Jason Campbell QB 6-5 233 offense off the field. -

GAME NOTES Patriots Vs

GAME NOTES Patriots vs. Indianapolis– November 21, 2010 SUSTAINED SUCCESS: PATRIOTS TO FINISH ABOVE .500 FOR 10th STRAIGHT SEASON With their eighth win of the 2010 season, the Patriots are guaranteed to finish the season with a record of .500 or better for the 10th consecutive year. At the conclusion of the 2010 season, the Patriots will be the only NFL team to finish with a record of .500 or better in each of the last 10 years (2001-2010). Each of the other 31 NFL teams had at least one losing season between 2001 and 2009. BRADY TIES FAVRE FOR MOST CONSECUTIVE HOME GAMES WON AS A STARTING QB Tom Brady won his 25th consecutive regular-season start at Gillette Stadium, tying Brett Favre’s post- merger NFL-record 25-game home winning streak. Favre won 25 home games in a row from 1995-98. The last time the Patriots lost a regular-season home game in which Brady started was on Nov. 12, 2006 against the New York Jets. MOST CONSECUTIVE REGULAR-SEASON HOME GAMES WON AS A STARTING QUATERBACK: Player Team Years Streak Tom Brady NE 2006-Present 25 Brett Favre GB 1995-98 25 John Elway DEN 1996-98 22 Bob Griese MIA 1971-74 20 Randall Cunningham PHI 1990-94 20 BELICHICK TIES JOE GIBBS FOR 11th PLACE IN NFL HISTORY WITH 171 WINS With the victory against the Colts, Bill Belichick passed Paul Brown and tied Joe Gibbs with his 171st career victory as a head coach, including playoff games. Belichick and Gibbs are tied for 11th in NFL history with 171 career victories. -

SCYF Football

Football 101 SCYF: Football is a full contact sport. We will help teach your child how to play the game of football. Football is a team sport. It takes 11 teammates working together to be successful. One mistake can ruin a perfect play. Because of this, we and every other football team practices fundamentals (how to do it) and running plays (what to do). A mistake learned from, is just another lesson in winning. The field • The playing field is 100 yards long. • It has stripes running across the field at five-yard intervals. • There are shorter lines, called hash marks, marking each one-yard interval. (not shown) • On each end of the playing field is an end zone (red section with diagonal lines) which extends ten yards. • The total field is 120 yards long and 160 feet wide. • Located on the very back line of each end zone is a goal post. • The spot where the end zone meets the playing field is called the goal line. • The spot where the end zone meets the out of bounds area is the end line. • The yardage from the goal line is marked at ten-yard intervals, up to the 50-yard line, which is in the center of the field. The Objective of the Game The object of the game is to outscore your opponent by advancing the football into their end zone for as many touchdowns as possible while holding them to as few as possible. There are other ways of scoring, but a touchdown is usually the prime objective. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Development, Evolution, and Bargaining in the National Football League

DEVELOPMENT, EVOLUTION, AND BARGAINING IN THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE Thomas Sisco The National Football League [hereinafter: NFL] is the most popular professional sports organization in the United States, but even with the current popularity and status of the NFL, ratings and the public perception of the on-field product have been on steady decline.1 Many believe this is a byproduct of the NFL being the only one of the 4 major professional sports leagues in the country without a self-controlled system for player development. Major League Baseball [hereinafter: MLB] has a prominent and successful minor league baseball system, the National Hockey League has the American Hockey League and East Coast Hockey League, the National Basketball Association [hereinafter: NBA] has the 22 team development league widely known as “The D- League”, but the NFL relies on the National Collegiate Athletic Association [hereinafter: NCAA] to develop young players for a career in their league. The Canadian Football League and the Arena Football League are generally inadequate in developing players for the NFL as the rules of gameplay and the field dimensions differ from those of NFL football.2 NFL Europe, a developmental league founded by Paul Tagliabue, former NFL Commissioner, has seen minor success.3 NFL Europe, existing by various names during its lifespan, operated from 1991 until it was disbanded in 2007.4 During its existence, the NFL Europe served as a suitable incubator for a 1 Darren Rovell, NFL most popular for 30th year in row, ESPN (January 26, 2014), http://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/10354114/harris-poll-nfl-most-popular-mlb-2nd, . -

Punt Defense Team

SPECIAL TEAMS 2007 vs. MONMOUTH vs. NEW HAMPSHIRE vs. NORTHEASTERN vs. NAVY vs. JAMES MADISON vs. RICHMOND vs. VILLANOVA NATIONAL RANKINGS Punting Not Ranked 77 Josh Brite PR Individual 66 56 A.Love S.McBride KR Individual 79 86 K. Michaud L.Moore FG Individual 8 3 J. Striefsky P.Gärtner PR Team 101 59 KR Team 91 6 PR Y Defense 10 23 KR Y Defense 43 33 PAT/FG TEAM 47 36 Rush Lanes Jump Lanes LB LB TE OL OL 49 OL OL DT SYSTEM ANALYSIS SUMMARY KICKER Regular Double Wing PAT/FG Solid PAT/FG Unit with a Freshman #47 Jon Striefsky Interior Line: Inside Zone Step Short Snapper. They didn’t faced Alignment: 3-2 Shoulder Down Protection real Rush this season. LT/RT Footed: Right TE & W: Man Protection The Operation Time is very slow: Approach: Soccer LS: Shoulder Down Protection Ø 1,42 sec. Steps: 3 (Jab, Drive & Plant) Get Off: 1,33 – 1,59 sec. PROTECTION Hash Tend: Always to the near Pole Block Tech: Inside Zone & Man ANY BLOCKED PAT/FG? Distance: 42Y Weakness: RG-RTE-LG-LTE NOPE Under Pressure: No Follow Thru! Block Point: 5Y How-When? Overall: Very consistent Kicker Overall Quality: Solid Protection! with a slow Operation Time. Weak over the Guards & the TE’s (Jumper > Edge) How-When? HOLDER SHORT SNAPPER #36 Ted Shea, SO (LS) #49 Zach Reed, FR Good Ball Handling, Can‘t reach! Good & accurate Short Snapper KEY OBSERVATIONS Has a very comfortable Stance! Average Speed, Shoulder Down Both Wings are Back Up LB! FAKES? SHIFTS/MOTION LTE is the Starting Left DT NOPE NOPE RTE is the Starting TE COVERAGE OPERATIONS STATS No Releases on FG‘s Get Off 1,33 – 1,59 sec. -

TONY GONZALEZ FACT SHEET BIOS, RECORDS, QUICK FACTS, NOTES and QUOTES TONY GONZALEZ Is One of Eight Members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2019

TONY GONZALEZ FACT SHEET BIOS, RECORDS, QUICK FACTS, NOTES AND QUOTES TONY GONZALEZ is one of eight members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2019. CAPSULE BIO 17 seasons, 270 games … First-round pick (13th player overall) by Chiefs in 1997 … Named Chiefs’ rookie of the year after recording 33 catches for 368 yards and 2 TDs, 1997 … Recorded more than 50 receptions in a season in each of his last 16 years (second most all-time) including 14 seasons with 70 or more catches … Led NFL in receiving with career-best 102 receptions, 2004 … Led Chiefs in receiving eight times … Traded to Atlanta in 2009 … Led Falcons in receiving, 2012… Set Chiefs record with 26 games with 100 or more receiving yards; added five more 100-yard efforts with Falcons … Ranks behind only Jerry Rice in career receptions … Career statistics: 1,325 receptions for 15,127 yards, 111 TDs … Streak of 211 straight games with a catch, 2000-2013 (longest ever by tight end, second longest in NFL history at time of retirement) … Career-long 73- yard TD catch vs. division rival Raiders, Nov. 28, 1999 …Team leader that helped Chiefs and Falcons to two division titles each … Started at tight end for Falcons in 2012 NFC Championship Game, had 8 catches for 78 yards and 1 TD … Named First-Team All- Pro seven times (1999-2003, TIGHT END 2008, 2012) … Voted to 14 Pro Bowls … Named Team MVP by Chiefs 1997-2008 KANSAS CITY CHIEFS (2008) and Falcons (2009) … Selected to the NFL’s All-Decade Team of 2009-2013 ATLANTA FALCONS 2000s … Born Feb.