How We Choose the Board of Education: the Case for Reform March 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice Systems Committee Meeting AGENDA

1220 Morello Ave, Suite 100 Contra Costa Martinez, California 94553 Health Services Ph (925) 957-2619 cchealth.org/mentalhealth/mhc To work through families and interagency collaborations to ensure that individuals, with mental illness in the justice system, are given respect, dignity and human rights. Justice Systems Committee Meeting Tuesday, August 25, 2020 ⬧ 1:30pm to 3:00pm Via: Zoom Teleconference: https://cchealth.zoom.us/j/6094136195 Meeting number: 609 413 6195 Join by phone: 1 646 518 9805 US Access code: 609 413 6195 AGENDA I. Call to Order / Introductions - Chair II. Public Comments III. Commissioner Comments IV. APPROVE minutes from the July 28, 2020 meeting V. RECEIVE Presentation from Marie Scannell (Program Manager) and Natalie Dimidjian (Program Supervisor) of Forensic Mental Health Services, Contra Costa Adult Mental Health regarding the Contra Costa Mobile Crisis Response Team (MCRT) VI. DISCUSS two articles from the San Francisco Chronicle concerning providing services for the homeless VII. DISCUSS the Contra Costa Mayors Conference to be held in September VIII. DISCUSS the Contra Costa Racial Justice Oversight Body IX. IDENTIFY Agenda items for the September 22, 2020 Justice Systems Committee meeting X. Adjourn The Contra Costa County Mental Health Commission is appointed by the Board of Supervisors to advise them on all matters related to the county’s mental health system, in accordance with mandates set forth in the California State Welfare & Institutions Code, Sections 5604 (a)(1)-5605.5. Any comments or recommendations made by the Mental Health Commission or its individual members do not represent the official position of the county or any of its officers. -

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, December 8, 2020 - 2:00 PM Held via Videoconference (remote public access provided via teleconference) www.sfgovtv.org Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Preston, Safai, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 115 Number 46 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 12/8/2020 Members Present: Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session through videoconferencing, and provided public comment through teleconferencing, on Tuesday, December 8, 2020, with President Norman Yee presiding. -

2021 Committee Assignments

President, Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco District 10 SHAMANN WALTON MEMORANDUM DATE: January 10, 2021 TO: Members of the Board of Supervisors FROM: President Shamann Walton CC: Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board of Supervisors Anne Pearson, Office of the City Attorney Board Legislative Aides SUBJECT: 2021 Board Committee Assignments Dear Supervisors, As we welcome our new colleagues to the Board of Supervisors, I am pleased to present updated Board Committee assignments for 2021. I am grateful to all of you for your input and collaboration. These appointments will go into effect immediately. Budget & Finance Committee Land Use & Transportation Committee Supervisor Matt Haney, Chair Supervisor Myrna Melgar, Chair Supervisor Ahsha Safai, Vice Chair Supervisor Dean Preston, Vice Chair Supervisor Gordon Mar, Member Supervisor Aaron Peskin, Member Budget & Appropriations Committee* Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee Supervisor Matt Haney, Chair Supervisor Gordon Mar, Chair Supervisor Ahsha Safai, Vice Chair Supervisor Catherine Stefani, Vice Chair Supervisor Gordon Mar, Member Supervisor Matt Haney, Member Supervisor Hillary Ronen, Member Supervisor Shamann Walton, Member Rules Committee Supervisor Aaron Peskin, Chair Government Audit & Oversight Committee Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, Vice Chair Supervisor Dean Preston, Chair Supervisor Connie Chan, Member Supervisor Connie Chan, Vice Chair Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, Member Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee** Supervisor Hillary Ronen, Chair Supervisor Ahsha Safai, Vice Chair Supervisor Matt Haney, Alternate Member * Pursuant to Section 3.25.1 of the Board of Supervisors’ Rules of Order, the Budget & Appropriations Committee shall convene year-round on an as needed basis determined by the President of the Board. -

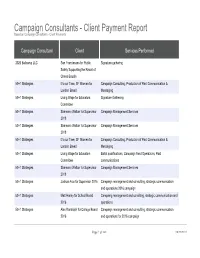

Campaign Consultants - Client Payment Report Based on Campaign Consultants - Client Payments

Campaign Consultants - Client Payment Report Based on Campaign Consultants - Client Payments Campaign Consultant Client Services Performed 2020 Ballcamp LLC San Franciscans for Public Signature gathering Safety Supporting the Recall of Chesa Boudin 50+1 Strategies It's our Time, SF Women for Campaign Consulting, Production of Paid Communication & London Breed Messaging 50+1 Strategies Living Wage for Educators Signature Gathering Committee 50+1 Strategies Shamann Walton for Supervisor Campaign Management Services 2018 50+1 Strategies Shamann Walton for Supervisor Campaign Management Services 2018 50+1 Strategies It's our Time, SF Women for Campaign Consulting, Production of Paid Communication & London Breed Messaging 50+1 Strategies Living Wage for Educators Ballot qualifications, Campaign Field Operations, Paid Committee communications 50+1 Strategies Shamann Walton for Supervisor Campaign Management Services 2018 50+1 Strategies Joshua Arce for Supervisor 2016 Campaign management and consulting, strategic communication and operations 2016 campaign 50+1 Strategies Matt Haney for School Board Campaing management and consilting, strategic communication and 2016 operations 50+1 Strategies Alex Randolph for College Board Campaign management and consulting, strategic communication 2016 and operations for 2016 campaign Page 1 of 360 09/29/2021 Campaign Consultants - Client Payment Report Based on Campaign Consultants - Client Payments Quarter Start Date Quarter End Date Year 03/01/2021 05/31/2021 2021 12/01/2017 02/28/2018 2018 12/01/2017 02/28/2018 -

SHUT IT DOWN! the Young Women’S Freedom Center’S Study Guide and Curriculum on the Movement to Shut Down San Francisco’S Juvenile Hall by 2021

SHUT IT DOWN! The Young Women’s Freedom Center’s Study Guide and Curriculum on the Movement to Shut Down San Francisco’s Juvenile Hall by 2021 This curriculum is dedicated to The youth of San Francisco, you are powerful and beautiful and deserve to be fought for. To the first champion of juvenile justice in San Francisco, Jean Jacobs. And to Ray Balberan, Alfredo “Fred” Bojorquez, Jim Queen and The Real Alternatives Program, who began the fight to shut down juvenile hall in the 1980s. We stand on your shoulders… Thank you to Ray Balberan and Roberto Ariel Vargas for sharing your knowledge with us. “A Society out of touch with the needs of its youth, is a society out of touch with its future.” - Art Brown, “Assignment Four: We’ll Do It Ourselves” KRON 1971 documentary report on SF community based programs serving youth. Written by Christina Gomez, The Young Women’s Freedom Center © 1 For the last 26 years, the Young Women’s Freedom Center has advocated for young people who have been detained and on probation in San Francisco’s juvenile justice system. While we are excited that our San Francisco Board of Supervisors has introduced legislation to shut down our local juvenile hall by 2021, we are more ecstatic that stakeholders are now asking questions and engaging in conversations about the validity of our current innovation of juvenile justice in our city and joining advocates to discuss what it will take to truly address the needs of San Francisco’s young people. But these conversations cannot happen without young people at the table, especially those that have experienced our local justice system. -

Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco Agenda

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AGENDA Watch SF Cable Channel 26, 78, or 99 (depending on your provider) Watch www.sfgovtv.org PUBLIC COMMENT CALL-IN 1 (415) 655-0001/ Meeting ID: 187 789 0947 # # Tuesday, May 18, 2021 - 2:00 PM Regular Meeting SHAMANN WALTON, PRESIDENT CONNIE CHAN, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, MYRNA MELGAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board Agendas of the Board of Supervisors are available on the internet at www.sfbos.org BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar, Ronen, Walton 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Preston, Chan, Mandelman 10:00 AM Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Melgar, Preston, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mar, Stefani, Haney 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Mandelman, Chan 10:00 AM Youth, Young Adult, and Families Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Ronen, Safai, Melgar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Agenda Item Information Each item on the Consent or Regular agenda may include the following documents: 1) Legislation 2) Budget and Legislative Analyst report 3) Department or Agency cover letter and/or report 4) Public correspondence These items will be available for review at City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 244, Reception Desk. -

Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco Agenda

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AGENDA Watch SF Cable Channel 26, 78, or 99 (depending on your provider) Watch www.sfgovtv.org PUBLIC COMMENT CALL-IN 1 (415) 655-0001/ Meeting ID: 146 520 5747 # # Tuesday, October 20, 2020 - 2:00 PM Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board Agendas of the Board of Supervisors are available on the internet at www.sfbos.org BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman, Yee, Ronen 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Preston 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Agenda Item Information Each item on the Consent or Regular agenda may include the following documents: 1) Legislation 2) Budget and Legislative Analyst report 3) Department or Agency cover letter and/or report 4) Public correspondence These items will be available for review at City Hall, 1 Dr. -

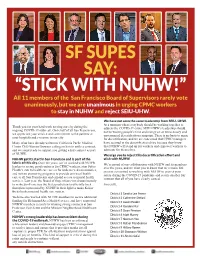

SF BOS Letter to CPMC Members

SF SUPES SAY: “STICK WITH NUHW!” All 11 members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors rarely vote unanimously, but we are unanimous in urging CPMC workers to stay in NUHW and reject SEIU-UHW. We have not seen the same leadership from SEIU–UHW. At a moment when everybody should be working together to Thank you for your hard work serving our city during the address the COVID-19 crisis, SEIU-UHW’s leadership should ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. On behalf of all San Franciscans, not be wasting people’s time and energy on an unnecessary and we appreciate your service and commitment to the patients at unwarranted decertification campaign. There is no basis to argue your hospitals and everyone in our city. for decertification, and we are concerned that CPMC managers Many of us have already written to California Pacfic Medical have assisted in the decertification drive because they know Center CEO Warren Browner calling on him to settle a contract, that NUHW will stand up for workers and empower workers to and we stand ready to support you getting a fair contract as part advocate for themselves. of NUHW. We urge you to reject this decertification effort and NUHW got its start in San Francisco and is part of the stick with NUHW. fabric of this city. Over the years, we’ve worked with NUHW We’re proud of our collaboration with NUHW and its members leaders to secure good contracts for CPMC workers, stop Sutter over the years, and we want you to know that we remain 100 Health’s cuts to health care access for underserved communities, percent committed to working with NUHW to protect your and initiate pioneering programs to provide universal health safety during the COVID-19 pandemic and secure another fair care to all San Franciscans and expand access to mental health contract that all of you have clearly earned. -

Contacting Your Legislators Prepared by the Government Information Center of the San Francisco Public Library - (415) 557-4500

Contacting Your Legislators Prepared by the Government Information Center of the San Francisco Public Library - (415) 557-4500 City of San Francisco Legislators Mayor London Breed Board of Supervisors voice (415) 554-6141 voice (415) 554-5184 fax (415) 554-6160 fax (415) 554-5163 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 200 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 244 San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 [email protected] [email protected] Members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors Sandra Lee Fewer Catherine Stefani Aaron Peskin District 1 District 2 District 3 voice (415) 554-7410 fax voice (415) 554-7752 fax (415) voice (415) 554-7450 fax (415) 554-7415 554-7843 (415) 554-7454 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Gordon Mar Vallie Brown Matt Haney District 4 District 5 District 6 voice (415) 554-7460 voice (415) 554-7630 voice (415) 554-7970 fax (415) 554-7432 fax (415) 554-7634 fax (415) 554-7974 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Norman Yee * Rafael Mandelman Hillary Ronen District 7 District 8 District 9 voice (415) 554-6516 voice (415) 554-6968 voice (415) 554-5144 fax (415) 554-6546 fax (415) 554-6909 fax (415) 554-6255 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Shamann Walton Ahsha Safaí District 10 District 11 voice (415) 554-7670 voice (415) 554-6975 fax (415) 554-7674 fax (415) 554-6979 [email protected] [email protected] *Board President California State Legislator Members from San Francisco Senate Scott Wiener (D) District 11 voice (916) 651-4011 voice (415) 557-1300 Capitol Office 455 Golden Gate Avenue, Suite State Capitol, Room 4066 14800 Sacramento, CA 95814-4900 San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected] Assembly David Chiu (D) District 17 Philip Y. -

Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco Agenda

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AGENDA Legislative Chamber, Room 250 City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 Watch SF Cable Channel 26, 78, or 99 (depending on your provider) Watch www.sfgovtv.org PUBLIC COMMENT CALL-IN 1 (415) 655-0001/ Meeting ID: 2491 975 9362 # # Tuesday, September 7, 2021 - 2:00 PM Regular Meeting SHAMANN WALTON, PRESIDENT CONNIE CHAN, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, MYRNA MELGAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board Agendas of the Board of Supervisors are available on the internet at www.sfbos.org BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar, Ronen, Walton 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Preston, Chan, Mandelman 10:00 AM Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Melgar, Preston, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mar, Stefani, Haney 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Mandelman, Chan 10:00 AM Youth, Young Adult, and Families Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Ronen, Safai, Melgar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Agenda Item Information Each item on the Consent or Regular agenda may include the following documents: 1) Legislation 2) Budget and Legislative Analyst report 3) Department or Agency cover letter and/or report 4) Public correspondence These items will be available for review at City Hall, 1 Dr. -

Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, July 14, 2020 - 2:00 PM Held via Videoconference (remote public access provided via teleconference) www.sfgovtv.org Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman, Yee, Ronen 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Preston 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 115 Number 28 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 7/14/2020 Members Present: Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session through videoconferencing, and provided public comment through teleconferencing, on Tuesday, July 14, 2020, with President Norman Yee presiding. -

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, December 22, 2020 - 10:00 AM Held via Videoconference (remote public access provided via teleconference) www.sfgovtv.org Special Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Preston, Safai, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 115 Number 48 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 12/22/2020 Members Present: Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in special session through videoconferencing, and provided public comment through teleconferencing, on Tuesday, December 22, 2020, with President Norman Yee presiding.