John Lewis Civil Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

The Black National Anthem

32 1 Table of Contents Page 3 Welcome Letter Pages 4-15 Paintings with Biographies Pages 16-24 Black Owned Businesses in Alphabetical Order Page 25 Importance of Supporting Black Owned Pages 26-27 Other Online Resources Pages 28-29 Lift Every Voice & Sing Page 30 Citations for Biographies & Contact Info Page 31 After the Peanut Advertisement A.F. Hill Park (Princeton St & Green Garden Pl) is getting a walking trail. It is about 1/3 of a mile and will be completed in the Spring of 2021! See image ← 2 31 CITATIONS (Painting Biographies) 2/6/2021 1. https://www.naacp.org/naacp-history-medgar-evers/ Dear Community Member, 2. https://aaregistry.org/story/an-exceptional-opera-singer-leontyne- price/ Thank you for coming to the drive-thru Black History Month Cel- 3. https://www.biography.com/news/duke-ellington-facts-duke-ellington- ebration! As hard as 2020 was, we did not want to cancel this day annual event but rather adapt and adjust in 2021. 4. https://www.americanswhotellthetruth.org/portraits/dick-gregory 5. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brooks- Adhering to COVID-19 safety precautions, we are unable to in- gwendolyn-1917/ 6. https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/P/POWELL,-Adam-Clayton,- vite you into our gymnasium at this time. We hope you to utilize Jr--(P000477)/ this booklet as a means to explore the people featured in the 7. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/biographical/ paintings at Fairmont Community Center (FCC) and for addition- 8. https://www.naacp.org/naacp-history-w-e-b-dubois/ al resources to help celebrate all month long. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

Power of the Hero Image: the Uniform, the Black Soldier and the Ku Klux Klan

POWER OF THE HERO IMAGE: THE UNIFORM, THE BLACK SOLDIER AND THE KU KLUX KLAN by Kevin M. Bair A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Baltimore, Maryland February 2020 © 2020 Kevin M. Bair All rights reserved Abstract Societies have long associated the image of the military uniform with social power and heroic abilities. This iconic image has both psychological power for the wearer and for those who observed the uniformed person. In the 19th and 20th centuries, whites and blacks looked upon this image as a tool to implement change. Some sought personal improvement while others looked for social transformation. In both instances, blacks who chose to don the military uniform of the United States were seeking upward mobility from their present situation, while some whites wanting to maintain the country’s segregation status quo wore the white robes of the Ku Klux Klan; thus believing in a different socially created image of power. In this article, we argue that the cultural and psychological power of the military uniform cannot be underestimated, and that this image, when worn by black military personnel, such as Private Henry Johnson, Sergeant Isaac Woodard, and Sergeant Medgar Evers, was intimidating to a number of whites. Additionally, we believe that black military personnel, like Johnson, Woodard and Evers, helped to bring widespread awareness of the vast social injustice occurring in this country to the greater public. Furthermore, we state that the image of, belief in, and donning of, the military uniform by blacks during the 19th and 20th centuries caused the end of America’s oppressive segregation laws, not only in desegregating the military (1948), but also helping topple Plessy vs. -

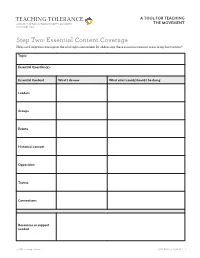

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the Satianal Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NfA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, .md areas of sIgnificance, ent.:r only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Other names/site number: Medgar Evers Historic District. _____ Name of related multiple property listing: (Enter liN/Ali if property is not part of a mUltiple property listing 2. Location Street & number: Margaret Walker Alexander Street roughly west of Missouri Street and east of Miami Street. _______________________ City or town: Jackson~=__---- State: Mississippi___ County: Hinds ______ Not For Publication: D Vicinity: D 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ~ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national .,£..statewide __local Applicable National Register Criteria: ~A .,£..B .,£..C _D Signature of certifying officialffitle: State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government 1 National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMS No. -

JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

ENTREE: A PICTURE WORTH A THOUSAND NARRATIVES JEWS and the FRAMING A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it’s often never quite as CIVIL RIGHTS simple as it seems. Begin by viewing the photo below and discussing some of the questions that follow. We recommend sharing more MOVEMENT background on the photo after an initial discussion. APPETIZER: RACIAL JUSTICE JOURNEY INSTRUCTIONS Begin by reflecting on the following two questions. When and how did you first become aware of race? Think about your family, where you lived growing up, who your friends were, your viewing of media, or different models of leadership. Where are you coming from in your racial justice journey? Please share one or two brief experiences. Photo Courtesy: Associated Press Once you’ve had a moment to reflect, share your thoughts around the table with the other guests. GUIDING QUESTIONS 1. What and whom do you see in this photograph? Whom do you recognize, if anyone? 2. If you’ve seen this photograph before, where and when have you seen it? What was your reaction to it? 3. What feelings does this photograph evoke for you? 01 JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT BACKGROUND ON THE PHOTO INSTRUCTIONS This photograph was taken on March 21, 1965 as the Read the following texts that challenge and complicate the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. marched with others from photograph and these narratives. Afterwards, find a chevruta (a Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in support of voting partner) and select several of the texts to think about together. -

1 John Lewis: a Conversation – Marching for Freedom

1 JOHN LEWIS: A CONVERSATION – MARCHING FOR FREEDOM CLOSED CAPTIONING SCRIPT Hoffman: Congressman John Lewis, I am so glad you’re here for this conversation. I’ve looked so forward to meeting you and --again I appreciate your time. Lewis: Well, I’m delighted and very pleased to be here. Susan, thank you for having me here. Hoffman: Over the next half hour my goal is to cover your pivotal role in the Civil Right Movement. I’d like you to begin with me here. In 1963, when you were 23, you were listed as one of the six primary leaders in the Civil Rights Movement. And I wonder, did you feel at 23 that you were ready for that awesome responsibility. Lewis: Well, at the age of 23, I had grown up a little. You must understand that I grew up in rural Alabama, fifty miles from Montgomery, and I came under the influence of Martin Luther King, Jr. I heard Dr. King’s voice. I heard his words on an old radio. I’d heard about Rosa Parks and T Montgomery Bus Boycott. I’d seen segregation. I’d seen racial discrimination. Hoffman: Describe those early signs that you remember as a young boy. Lewis: Well I saw the signs that said “White Men,” “Colored Men,” “White Women,” “Colored Women,” “White Waiting,” “Colored Waiting.” I didn’t like it. As a child, I would ask my mother, my father, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, “Why segregation? Why racial discrimination?” And they would say, “That’s the way it is. -

Here All Proceeds Will Go Directly Towards the Production of the Play

“For the LORD does not see as man sees, for man looks at the outward appearance, but the LORD looks at the heart.” 1 Samuel 16:7 It’s becoming alarmingly apparent that racial injustice must be met with swift consequence, if we are to put an end to the racial inequities and blatant disregard for black lives in our country. However, it stands to reason that if we don’t repair the injustices of the past, consistently, and methodically, we certainly can’t expect any real change in the present, as we all know that history has a tendency to repeat itself. The past by its very nature will echo the injustices it suffered, but we must declare the advancements of our civil rights predecessors, diligently and thunderously. While we can't change how things transpired, or the lives lost in this insidious battle, we must honor the civil rights trail blazers that lit the way. Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore are the undisputed pioneer leaders and first martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement in our country. HARRY T. MOORE Pioneer Leader & Martyr of the Civil Rights Movement In his quest for justice and equality, Harry T. Moore knew that real change would require him to live without fear and stand steadfast in his faith with little concern for the establishments that would make it their mission to prevent his progress and worse. That is exactly what he did as he sought to amplify the voices of blacks during a time that wanted nothing more than to silence them in whatever fashion they deemed necessary. -

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American Gandhians Sue Bailey and Howard Thurman Howard Thurman (1899–1981) was a prominent theologian and civil rights leader who served as a spiritual mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. Sue Bailey Thurman, (1903–1996) was an American author, lecturer, historian and civil rights activist. In 1934, Howard and Sue Thurman, were invited to join the Christian Pilgrimage of Friendship to India, where they met with Mahatma Gandhi. When Thurman asked Gandhi what message he should take back to the United States, Gandhi said he regretted not having made nonviolence more visible worldwide and famously remarked, "It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world." In 1944, Thurman left his tenured position at Howard to help the Fellowship of Reconciliation establish the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. He initially served as co-pastor with a white minister, Dr. Alfred Fisk. Many of those in congregation were African Americans who had migrated to San Francisco for jobs in the defense industry. This was the first major interracial, interdenominational church in the United States. “It is to love people when they are your enemy, to forgive people when they seek to destroy your life… This gives Mahatma Gandhi a place along side all of the great redeemers of the human race. There is a striking similarity between him and Jesus….” Howard Thurman Source: Howard Thurman; Thurman Papers, Volume 3; “Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi:” February 1, 1948; pp. 260 Benjamin Mays (1894–1984) -was a Baptist minister, civil rights leader, and a distinguished Atlanta educator, who served as president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967. -

Civil Rights Done Right a Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE

Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE Table of Contents Introduction 2 STEP ONE Self Assessment 3 Lesson Inventory 4 Pre-Teaching Reflection 5 STEP TWO The "What" of Teaching the Movement 6 Essential Content Coverage 7 Essential Content Coverage Sample 8 Essential Content Areas 9 Essential Content Checklist 10 Essential Content Suggestions 12 STEP THREE The "How" of Teaching the Movement 14 Implementing the Five Essential Practices 15 Implementing the Five Essential Practices Sample 16 Essential Practices Checklist 17 STEP FOUR Planning for Teaching the Movement 18 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 19 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Sample 23 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 27 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 Sample 30 STEP FIVE Teaching the Movement 33 Post-Teaching Reflection 34 Quick Reference Guide 35 © 2016 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT // 1 TEACHING TOLERANCE Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Not long ago, Teaching Tolerance issued Teaching the Movement, a report evaluating how well social studies standards in all 50 states support teaching about the modern civil rights movement. Our report showed that few states emphasize the movement or provide classroom support for teaching this history effectively. We followed up these findings by releasingThe March Continues: Five Essential Practices for Teaching the Civil Rights Movement, a set of guiding principles for educators who want to improve upon the simplified King-and-Parks-centered narrative many state standards offer. Those essential practices are: 1. Educate for empowerment. 2. Know how to talk about race. 3. Capture the unseen. 4. Resist telling a simple story. -

Letter to Polly Greenberg Re Medgar Evers, September 1966

No ta (Ap ril 1969): Mr s . Gr eenbe r g , a quite lihPr al lady from New Yn rk, w ~s spend~n ~ _s om P time in Jackson a n d , among other thin~s , wq s _rl1 g~1n~ up m~ terial nn Ne rl~nr Ev er s . She t elephoned me_1n RalPlgh, we talked exten s ively about Med gar , a n d th1s l e tte r tn her "'rtS arlctitional info rmation of a n essentirtlly anecdotal na ture. jrs John ~ L Se.ltor, Jr. September 27, 1966 62S Ne"rcombe .1. oad ~1alei!j1, North Carolina r.Ki~!J Poll y Greenberg 4221 Forest Park Drive Jackson, Mississipid Dear Miss Greenbergs It was indeed good to talk with you on the phone. Your moral support is much appreciated, believe me. I knew Medgar Evers very well from 1961 to hi~ death. I was the Advisor to the Jackson Youth Council of the NAACP, a member of the bonrd of directors of the Mississippi NAACP, and co-chairman of the strategy committee of ·the Jackson Movement. I '\«>rked with Jl1edgnr closely. And I always had tremendous respect for him. Here are t~~ or three of the many sketches that come to mind: r-iedgar 1'/as a very stable, very cool person. The only time that I ever saw him brea_....k down came in the fall of 1961, at r.m evening dinner session of the annual convention of the Mississippi NAACP -- in the ?-1asonic Temple on Lynch Street. The police were parked out side nnd , inside, the delega~es frcU~ the scattered, ~nd senel"ally moribund NAACP units around the state, had finished e ivinG their reports.