Blow out (1981)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

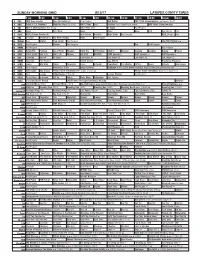

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

BRICE DELLSPERGER Solitaires

**click here to access to the french version** BRICE DELLSPERGER Solitaires Exhibition from June 20 to July 30, 2020 43, rue de la Commune de Paris F-93230 Romainville For his new solo sow at Air de Paris, Brice Dellsperger presents two new films «Body Double 36» and «Body Double 37». «My Body Double videos are like doubles of movie sequences from the 70s or 80s: the title refers to Brian de Palma’s film (Body Double, 1984). To this day the series includes forty films with various running times, where the obsessive motif is the body of the double in mainstream movies. Following a rigorous but emancipating process, each selected scene is re-enacted by a single transvestite actor or actress, a super character who interprets all the parts by becoming double.» By appropriating the linear/ authoritarian form of a movie, the Body Double films aim at disrupting normative sexual genres through the means of a camp aesthetic.» Body Double 36 (2019) After Perfect (James Bridges, 1985) with Jean Biche. Aerobics were the fashion in the 80s! James Bridges’ Perfect was released in 1985. The film superficially describes human relationships in a gym club in Los Angeles, seen through the eyes of a journalist (John Travolta) who is beguiled by an androgynous gym coach (Jamie Lee Curtis). Studies on the postmodern body in contemporary American society are linked to the context of the 80s, a period which recognized an ideal body-object caught up by the AIDS epidemic. The identification of the HIV virus had a major influence on the perception and representation of bodies and sexuality. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

The Talk of the Town Continues…

The Talk of the Town continues… “Kay Thompson was a human dynamo. My brothers and I were constantly swept up by her brilliance. Sam Irvin has captured all of this in his incredible book. I know you will thoroughly enjoy reading it.” – DON WILLIAMS, OF KAY THOMPSON & THE WILLIAMS BROTHERS “It’s an amazing book! Sam Irvin has captured Ms. T. to a T. I just re-read it and liked it even better the second time around.” – DICK WILLIAMS, OF KAY THOMPSON & THE WILLIAMS BROTHERS “To me, Kay was the Statue of Liberty. I couldn’t imagine how a book could do her justice but, by golly, Sam Irvin has done it. You won’t be able to put it down.” – BEA WAIN, OF KAY THOMPSON’S RHYTHM SINGERS “Kay was the hottest thing that ever hit the town and one of the most captivating women I’ve ever met in my life. There’ll never be another one like her, that’s for sure. A thorough examination of her astounding life was long overdue and I can’t imagine a better portrait than the one Sam Irvin has written. Heaven.” – JULIE WILSON “This fabulous Kay Thompson book totally captured her marvelous enthusiasm and talent and I’m delighted to be a part of it. I adore the cover with enchanting Eloise and the great picture of Kay in all her intense spirit!” – PATRICE MUNSEL “Thank you, Sam, for bringing Kay so richly and awesomely ‘back to life.’ Adventuring with Kay through your exciting book is like time-traveling through an incredible century of showbiz.” – EVELYN RUDIE, STAR OF PLAYHOUSE 90: ELOISE “At Metro… she scared the shit out of me! At Paramount… while shooting Funny Face… I got to know and love her. -

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Professors Explore Foreign Policy, Election Tryouts Commence To

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY V OLUME 50, ISSUE 127 | WEDNESDAY, APRIL 20, 2016 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM P rofessors explore foreign policy, election ND Votes “Pizza, Pop and Politics” hosts discussion on foreign policy issues in the presidential election By LUCAS MASIN-MOYER issues, ” Desch said. N ews Writer Desch said this change in sentiment was largely due ND Votes hosted their final to “war weariness” and said installment of “Pizza, Pop, American voters are much and Politics” on Tuesday night more skeptical of involvement with Michael Desch, professor in foreign conflicts. of political science, and Mary “American voters are asking Ellen O’Connell, the Robert and the question, ‘What’s in it for Marion Short Professor of Law us?’ They want to be persuaded and research professor of in- that, if we go abroad in search ternational dispute resolution, of a monster, these are mon- speaking on issues of foreign sters that is in the interest of the policy related to the 2016 U.S. United States to slay,” he said. presidential election. Desch also touched upon the Desch began by speaking on seeming continuity between domestic public sentiment on candidates of the major parties United States foreign policy. on issues of foreign policy. “The message in 2014 and “Clinton and Cruz both be- 2015 is that there is a signifi- lieve that the United States GRACE TOURVILLE | The Observer cant uptick in the public’s pri- Michael Desch speaks Tuesday night in the Geddes Coffeehouse at the final “Pizza, Pop and Politics,” oritization of domestic political see POLICY PAGE 5 hosted by ND Votes. -

Rétrospective – Le Secret

Rétrospective – Le Secret Blow out, de Brian de Palma USA – 1981 – 1h47 - Couleur Fiche pédagogique rédigée par Sébastien Perreux Scénario : Brian de Palma Image : Vilmos Zsigmond Montage : Paul Hirsch Musique : Pino Donaggio Interprètes : John Travolta, Nancy Allen, John Lithgow Synopsis Jack est preneur de son dans le cinéma, et cherche un cri effroyable pour le film d’horreur sur lequel il travaille. Une nuit, alors qu’il capte des bruits dans la nature, il assiste à un accident de voiture dont il enregistre chaque détail sonore. Voyant que la voiture passe à travers la balustrade d’un pont et tombe à l’eau, il se jette au secours des passagers. Puis le lendemain, en écoutant l’enregistrement de l’accident de la veille, il se rend compte que le hasard n’y est sûrement pour rien. Avant la projection Biographie *Cinéaste américain né en 1940 d’origine italienne comme beaucoup d’autres grands réalisateurs de cette époque (Scorsese, Coppola…), même si ses origines n’auront pas autant d’importance dans son œuvre que pour ses contemporains. *C’est un adolescent plutôt doué, même plus, qui témoigne de vraies aptitudes pour les sciences et se lance dans l’invention de petites machines, encouragé en cela par des parents assez exigeants du point de vue de l’éducation. *A noter, trois chocs vécus dans sa jeunesse, tous essentiels dans la construction de sa personnalité : *Choc intime, personnel. Un épisode de sa jeunesse, moins anecdotique qu’il n’y paraît et dont on trouve des traces dans sa filmographie lorsque le jeune Brian découvrit sa mère inanimée, après qu’elle eut tenté de mettre fin à ses jours, du fait des infidélités à répétition du père. -

NEO-NOIR / RETRO-NOIR FILMS (1966 Thru 2010) Page 1 of 7

NEO-NOIR / RETRO-NOIR FILMS (1966 thru 2010) Page 1 of 7 H Absolute Power (1997) H Blondes Have More Guns (1995) H Across 110th Street (1972) H Blood and Wine (1996) H Addiction, The (1995) FS H Blood Simple (1985) h Adulthood (2008) H Blood Work (2002) H Affliction (1997) H Blow Out (1981) FS H After Dark, My Sweet (1990) h Blow-up (1967).Blowup H After Hours (1985) f H Blue Desert (1992) F H Against All Odds (1984) f H Blue Steel (1990) f H Alligator Eyes (1990) SCH Blue Velvet (1986) H All the President’s Men (1976) H Bodily Harm (1995) H Along Come a Spider (2001) H Body and Soul (1981) H Ambushed (1998) f H Body Chemistry (1990) H American Gangster (2007) H Body Double (1984) H American Gigolo (1980) f H Bodyguard, The (1992) H Anderson Tapes, The (1971) FSCH Body Heat (1981) S H Angel Heart (1987) H Body of Evidence (1992) f H Another 48 Hrs. (1990) H Body Snatchers (1993) F H At Close Range (1986) H Bone Collector, The (1999) f H Atlantic City (1980) H Bonnie & Clyde (1967) f H Bad Boys (1983) F H Border, The (1982) F H Bad Influence (1990) F H Bound (1996) F H Badlands (1973) H Bourne Identity, The (2002) F H Bad Lieutenant (1992) H Bourne Supremacy, The (2004) h Bank Job, The (2008) H Bourne Ultimatum, The (2007) F H Basic Instinct (1992) H Boyz n the Hood (1991) H Basic Instinct 2 (2006) H Break (2009) H Batman Begins (2005) H Breakdown (1997) F H Bedroom Window, The (1987) F H Breathless (1983) H Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) H Bright Angel (1991) H Best Laid Plans (1999) H Bringing Out the Dead (1999) F H Best -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

(XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: the UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 Min

November 8, 2016 (XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: THE UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot url links.) DIRECTED BY Brian De Palma WRITING CREDITS David Mamet (written by), Oscar Fraley & Eliot Ness (suggested by book) PRODUCED BY Art Linson MUSIC Ennio Morricone CINEMATOGRAPHY Stephen H. Burum FILM EDITING Gerald B. Greenberg and Bill Pankow Kevin Costner…Eliot Ness Sean Connery…Jimmy Malone Charles Martin Smith…Oscar Wallace Andy García…George Stone/Giuseppe Petri Robert De Niro…Al Capone Patricia Clarkson…Catherine Ness Billy Drago…Frank Nitti Richard Bradford…Chief Mike Dorsett earning Oscar nominations for the two lead females, Piper Jack Kehoe…Walter Payne Laurie and Sissy Spacek. His next major success was the Brad Sullivan…George controversial, ultra-violent film Scarface (1983). Written Clifton James…District Attorney by Oliver Stone and starring Al Pacino, the film concerned Cuban immigrant Tony Montana's rise to power in the BRIAN DE PALMA (b. September 11, 1940 in Newark, United States through the drug trade. The film, while New Jersey) initially planned to follow in his father’s being a critical failure, was a major success commercially. footsteps and study medicine. While working on his Tonight’s film is arguably the apex of De Palma’s career, studies he also made several short films. At first, his films both a critical and commercial success, and earning Sean comprised of such black-and-white films as Bridge That Connery an Oscar win for Best Supporting Actor (the only Gap (1965). He then discovered a young actor whose one of his long career), as well as nominations to fame would influence Hollywood forever.