Memorandum in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Care: Estimating Leading Democratic Candidates' Health Plans

CHAIRMEN Primary Care: MITCH DANIELS Estimating Leading Democratic Candidates’ Health Plans LEON PANETTA US Budget Watch 2020 TIM PENNY January 24, 2020 PRESIDENT Health care is the single largest part of the federal budget and a key driver of our MAYA MACGUINEAS unsustainably rising national debt.1 Rising health care costs also place growing burdens on households and businesses and – along with a significant uninsured rate DIRECTORS BARRY ANDERSON – have prompted those seeking higher office to propose bold solutions with ERSKINE BOWLES significant fiscal implications. CHARLES BOWSHER KENT CONRAD As part of our US Budget Watch 2020 project, the Committee for a Responsible Federal DAN CRIPPEN Budget has analyzed the plans of the four candidates polling the highest in the VIC FAZIO WILLIS GRADISON majority of national polls and polls in the first four primary states: Vice President Joe JANE HARMAN Biden, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Senator Bernie Sanders, and Senator Elizabeth Warren. WILLIAM HOAGLAND JIM JONES For each plan, we score the fiscal impact of coverage and other spending provisions, LOU KERR JIM KOLBE reductions in current and proposed health care costs, direct offsets proposed as part MARJORIE MARGOLIES of their plans to expand coverage, and further offsets meant to finance remaining DAVE MCCURDY costs. We focus on federal fiscal impact rather than the effect on total national health JAMES MCINTYRE, JR. expenditures. DAVID MINGE MARNE OBERNAUER, JR. JUNE O’NEILL Our estimates are rough and rounded, based on our best understanding of how PAUL O’NEILL campaign-level detail translates into specific policies, and subject to change as more RUDOLPH PENNER details are made available.2 This report is for educational purposes and does not ROBERT REISCHAUER represent an endorsement of any candidate or any policy. -

Ipsos Poll Conducted for Thomson Reuters Core Political Data

Ipsos Poll Conducted for Thomson Reuters Core Political Data AUGUST 7, 2019 © 2019 Ipsos. All rights reserved. Contains Ipsos' Confidential and Proprietary information and may not be disclosed or reproduced without the prior written consent of Ipsos. © 2019 Ipsos 1 IPSOS POLL CONDUCTED FOR REUTERS Core Political Data These are findings from an Ipsos poll conducted for date August 1-5, 2019 For the survey, a sample of including ages 2,129 1,795 807 772 140 Registered Democratic Republican Independent 18+ Americans Voters Registered Registered Registered Voters Voters Voters were interviewed online © 2019 Ipsos 2 IPSOS POLL CONDUCTED FOR REUTERS Core Political Data The precision of the Reuters/Ipsos online polls is measured using a credibility interval. In this case, the poll has a credibility interval of plus or minus the following percentage points 2.4 2.6 3.9 4.0 9.4 All Adults All Registered Democratic Republican Independent Voters Registered Voters Registered Voters Registered Voters For more information about credibility intervals, please see the appendix. © 2019 Ipsos 3 IPSOS POLL CONDUCTED FOR REUTERS Core Political Data • The data were weighted to the U.S. current population data by: – Gender – Age – Education – Ethnicity – Region • Statistical margins of error are not applicable to online polls. • All sample surveys and polls may be subject to other sources of error, including, but not limited to coverage error and measurement error. • Figures marked by an asterisk (*) indicate a percentage value of greater than zero but less than one half of one per cent. • Where figures do not sum to 100, this is due to the effects of rounding. -

Biden Is Only Leading Dem to Top Trump in Ohio, Quinnipiac University Poll Finds; Former V.P

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director (203) 535-6203 Rubenstein Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: JULY 25, 2019 BIDEN IS ONLY LEADING DEM TO TOP TRUMP IN OHIO, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; FORMER V.P. HAS BIG LEAD IN DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY Former Vice President Joseph Biden leads President Donald Trump 50 – 42 percent in the critical swing state of Ohio, the only leading Democratic candidate to top the Republican incumbent, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. The other leading Democratic contenders each are locked in a dead heat with President Trump, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds: 46 percent for Trump to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders with 45 percent; Trump at 46 percent to Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren at 45 percent; 44 – 44 percent between Trump and California Sen. Kamala Harris; 44 – 44 percent between Trump and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg; 44 percent for Trump to 43 percent for New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker. Women, black voters and independent voters give Biden his lead in the matchup with Trump. Biden leads 53 – 40 percent among women, as men are split with 46 percent for Biden and 45 percent for Trump. White voters are divided, with 48 percent for Trump and 45 percent for Biden. Black voters go Democratic 84 – 8 percent. Independent voters go to Biden 55 – 32 percent. Republicans back Trump 86 – 10 percent as Biden leads 96 – 2 percent among Democrats. “Former Vice President Joseph Biden calls himself a blue-collar guy. With Ohio certainly a blue-collar state, it is no surprise he is the Democrat who runs best against President Donald Trump and is solidly ahead in the Democratic primary in the Buckeye State,” said Peter Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Poll. -

Omnibus October 2019 Dem Primary

Democratic Primary Update Verified Voter Omnibus Survey N=449 Democratic or Democratic Leaning Likely Primary Voters October 21 - October 25, 2019 X1 Key Findings • Joe Biden continues to lead the field of 19 Democratic Presidential candidates tested, receiving 32 percent support among likely Democratic primary voters, or about consistent with his 30 percent support among Democratic voters in August. • Biden runs 10 points ahead of Elizabeth Warren, and Biden leads by 6 among likely Democratic primary voters who with a verified history of voting in primary elections. • Bernie Sanders and Kamala Harris each saw declines in support since August, with Sanders receiving 15 percent of the vote share from 19 percent in August, and Harris dropping to 5 percent, from 11 percent in August. • This puts Harris on even footing with Pete Buttigieg, who secured the support of 6 percent of likely Democratic voters, up 3 points from August. • Movement in head to head match-ups against Biden reflect recent shifts in support. In August, Biden held a 20 point advantage against Warren in a head to head match-up. Today, Biden’s lead against Warren narrowed to 11 points. • Conversely, Biden’s advantage in head to head match-ups against both Sanders and Harris widened since August. • In August, Biden led Sanders by 20 points; today, Biden leads Sanders by 31 points. • In August, Biden led Harris by 24 points; today, Biden leads Harris by 37 points. 2 Methodology • Using a voter file-matched online panel, we surveyed n=1,002 registered voters across the country from October 21 to October 25, 2019, with a sample of 449 Democratic or Democratic-leaning Independent Likely Voters. -

Voter Intent Posters

envelope Democratic Sort 2 Mark one party declaration box (required) Democratic Party X decare that m art preference i the Democratic Part an wil not Tabulate articiate i the nomiatio roce o an other politica art for the 202 Presidentia election. Republican Party decare that am a Republica an have not particiate an wil not articiate i the 202 precict caucu or conventio system o an other arty. Declared-party Ballot, Declared-party Ballot, Declared-party Ballot ballot Write-in ballot Overvote ballot Deocratic Party Republican Party Deocratic Party Republican Party Deocratic Party Republican Party I you ared Deocratic Party on I you ared Republican Party on I you ared Deocratic Party on I you ared Republican Party on I you ared Deocratic Party on I you ared Republican Party on your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote your return envelope, you ust vote or O Deocratic candidate below. or O Republican candidate below. or O Deocratic candidate below. or O Republican candidate below. or O Deocratic candidate below. or O Republican candidate below. icae eet Doa Trm icae eet Doa Trm icae eet Doa Trm oe ie __________________________ oe ie __________________________ oe ie __________________________ icae oomer icae oomer icae oomer or ooer or ooer or ooer ete ttiie ete ttiie ete ttiie o Deae o Deae o Deae i aar i aar i aar m ocar m ocar m ocar Dea atric Dea atric Dea atric erie Saer erie Saer erie Saer om Steer om Steer om Steer iaet arre iaet arre iaet arre re a re a re a committe Deeate committe Deeate committe Deeate __________________________ __________________________A. -

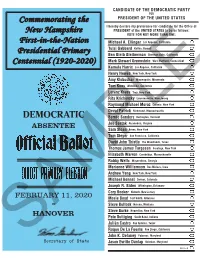

Commemorating the New Hampshire First-In-The

CANDIDATE OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY FOR Commemorating the PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES &DANA>U@A?H=NAIULNABANAJ?ABKN?=J@E@=PABKNPDA,Bł?AKB New Hampshire PRESIDENT of the UNITED STATES to be as follows: VOTE FOR NOT MORE THAN ONE: First-in-the-Nation Michael A. Ellinger Los Angeles, California Tulsi Gabbard Kailua, Hawaii Presidential Primary Ben Gleib Gleiberman Sherman Oaks, California Centennial (1920-2020) Mark Stewart Greenstein West Hartford, Connecticut Kamala Harris Los Angeles, California Henry Hewes New York, New York Amy Klobuchar Minneapolis, Minnesota Tom Koos Woodside, California Lorenz Kraus Troy, New York Rita Krichevsky Lawrenceville, New Jersey Raymond Michael Moroz Colonie, New York Deval Patrick Richmond, Massachusetts Bernie Sanders Burlington, Vermont ABSENTEE Joe Sestak Alexandria, Virginia Sam Sloan Bronx, New York Tom Steyer San Francisco, California David John Thistle The Woodlands, Texas Thomas James Torgesen Saratoga, New York Elizabeth Warren Cambridge, Massachusetts Robby Wells Waynesboro, Georgia Marianne Williamson Des Moines, Iowa Andrew Yang New York, New York Michael Bennet Denver, Colorado Joseph R. Biden Wilmington, Delaware FEBRUARY 11, 2020 Cory Booker Newark, New Jersey Mosie Boyd Fort Smith, Arkansas IN Steve Bullock Helena, Montana HANOVER Steve Burke Heuvelton, New York Pete Buttigieg South Bend, Indiana Julián Castro San Antonio, Texas Roque De La Fuente San Diego, California John K. Delaney Potomac, Maryland SAMPLESecretary of State Jason Evritte Dunlap Odenton, Maryland WRITE-IN. -

Secretary Buttigieg

June 15, 2021 The Honorable Pete Buttigieg U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Secretary Buttigieg, As representatives of more than one hundred businesses and nonprofits from the Metropolitan Washington region, we write to you today to thank you for your commitment to furthering our nation's rich legacy of innovative investments in transportation and infrastructure with the Amer- ican Jobs Plan. As the administration and Congress seek to spur investments in transportation and infrastructure, we urge you to support funding the $10.7 billion Washington Union Station Expansion Project (SEP). As Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s (WMATA) and Maryland Area Regional Commuter’s (MARC) busiest station and the Virginia Railway Express’s (VRE) second busiest, Union Station requires immediate investments for its expansion and redevelopment. Serving over 100,000 passengers each day, Washington Union Station is the heart of the Nation’s Capital and the gateway to the most heavily used rail corridor in the Western hemisphere. Over the next dec- ade, ridership volumes on Amtrak, MARC, and VRE are estimated to reach two or three times their pre-pandemic levels. Despite its central and essential role, the station has not seen any in- frastructure improvements since the 1990s. It has a dangerous backlog of deferred maintenance that presents significant ADA access, safety, and security issues. Without a serious upgrade, it will struggle to handle riders—and deliver national, regional, and local economic benefits. This year the Federal Railroad Administration, in collaboration with Amtrak and the Union Station Redevelopment Corporation, will unveil the ten-year, $10.7 billion Washington Union Station Ex- pansion Project (SEP) to modernize facilities and create a world-class multimodal transit hub. -

Biden and Warren Trail 2/9/2020

CNN 2020 NH Primary Poll February 9, 2020 SANDERS'S LEAD OVER BUTTIGIEG IN NH HOLDING STEADY; BIDEN AND WARREN TRAIL By: Sean P. McKinley, M.A. [email protected] Zachary S. Azem, M.A. 603-862-2226 Andrew E. Smith, Ph.D. cola.unh.edu/unh-survey-center DURHAM, NH – With three days of campaigning le before the votes are counted in New Hampshire, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders maintains a slim lead over former South Bend (IN) Mayor Pete Bu gieg among likely Democra c voters. Former Vice President Joe Biden and Massachuse s Senator Elizabeth Warren con nue to trail, with Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, Hawaii Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard, and entrepreneur Andrew Yang further back. Klobuchar has experienced a slight up ck in support since the last polling period and now sits in fi h place. Sanders con nues to hold a sizeable lead among self-described liberal likely Democra c voters while Bu gieg leads among moderates and conserva ves. These findings are based on the latest CNN 2020 New Hampshire Primary Poll*, conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center. Seven hundred sixty-five (765) randomly selected New Hampshire adults were interviewed in English by landline and cellular telephone between February 5 and February 8, 2020. The margin of sampling error for the survey is +/- 3.5 percent. Included in the sample were 384 likely 2020 Democra c Primary voters (margin of sampling error +/- 5.0 percent) and 227 likely 2020 Republican Primary voters (margin of sampling error +/- 6.5 percent). Trend points prior to July 2019 reflect results from the Granite State Poll, conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center. -

Omnibus January 2020 Dem Primary

Democratic Primary Update Verified Voter Omnibus Survey N=474 Democratic or Democratic Leaning Likely Primary Voters January 20 - January 23, 2020 X1 Key Findings • Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders are leading the field with a 3 point margin between the two candidates: Biden fell 11 points since December to 26% of the likely Democratic vote and Sanders gained 9 points to 23% of the likely Democratic vote. • Among likely Democratic voters with a verified history of voting in primary elections, Biden received 26% of the vote to Sanders’ 22%. • Mike Bloomberg also showed strong momentum since December, with Bloomberg gaining 7 points to 13% of the likely Democratic vote. Elizabeth Warren earned 10% and Pete Buttigieg earned7% of the likely Democratic vote. • Biden’s lead against top candidates in direct match ups narrowed across the board since December, and narrowed most significantly against Warren, where Biden led 48-43, from 59-29 in December. • Biden led Sanders 54-38 in a direct match up this month and led Buttigieg 56-32. 2 Methodology • Using a voter file-matched online panel, we surveyed n=1,000 registered voters across the country from January 20 - January 23, 2019, with a sample of 474 Democratic or Democratic-leaning Independent Likely Voters. • With our eight monthly tracking survey on the 2020 political landscape, we were able to track changes in the attitudes and behaviors of key voters since our last survey of verified Democratic or Democratic-leaning Independent Likely Voters from December 9 - December 14, 2019 3 The Democratic Primary 4 Biden, Sanders Neck & Neck, Bloomberg at 13% Q. -

BIDEN HOLDS COMMANDING LEAD in ILLINOIS on EVE of SECOND DEBATE Biden Leads Nearest Competitor Sanders by More Than 2-1 Margin in Illinois

BIDEN HOLDS COMMANDING LEAD IN ILLINOIS ON EVE OF SECOND DEBATE Biden Leads Nearest Competitor Sanders By More Than 2-1 Margin in Illinois July 30, 2019 For more information For immediate release Contact 312-388-1782 Former Vice President Joe Biden holds a commanding lead in Illinois heading into the second presidential debate, according to a new poll. Biden has 36.1% of the vote, with Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders in second place with 15.2%. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren is in third place with 12.8%, while South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg (9.3%), and California Senator Kamala Harris (8.6%) round out the top tier of candidates. The poll, conducted between July 26th-29th, of 1200 Democratic primary voters across Illinois, is part of The Illinois Poll, a semi monthly survey by Victory Research, an independent polling company based in Chicago. The poll has a margin of error of 2.83% and was conducted by live callers. Respondents answered on land lines (502) and cell phones (698). Victory Research has no client in the Presidential campaign. Victory Research was the most accurate Illinois polling company for the 2018 gubernatorial election. The final Illinois poll of the 2018 Illinois Governor election published the day before the election showed Governor Prizker’s lead over former Governor Rauner at 16%. The actual margin of victory was 15.7%. Biden’s lead is built on a very strong showing among African-American voters. More than half of African- American voters (54.2%) choose President Obama’s running mate as their first choice for President, according to the poll. -

Suffolk University/Boston Globe

SUPRC/Boston Globe August 2019 FINAL NH DEM PRIMARY AUGUST Region: (N=500) n % West/North ------------------------------------------------------- 131 26.20 Central ------------------------------------------------------------ 127 25.40 Hillsborough ------------------------------------------------------ 137 27.40 Rockingham ------------------------------------------------------ 105 21.00 INTRO SECTION> Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk (SUFF-ick) University and I would like to get your opinions on some questions about the upcoming Democratic Primary in New Hampshire. Would you be willing to spend five minutes answering some brief questions? (quota) A. Are you a resident of New Hampshire? (N=500) n % Yes ----------------------------------------------------------------- 500 100.00 1. Gender (N=500) n % Male ---------------------------------------------------------------- 224 44.80 Female ------------------------------------------------------------ 276 55.20 2. Thinking about the Democratic Primary for President coming up in six months, how likely are you to vote in the Democratic Primary – would you say you are very likely, somewhat likely, not very likely, or not at all likely to vote in the Democratic Primary? (N=500) n % Very likely--------------------------------------------------------- 448 89.60 Somewhat likely -------------------------------------------------- 52 10.40 3. Are you currently enrolled as a Democrat, Republican, or Undeclared/Independent? (N=500) n % Democrat --------------------------------------------------------- -

Indivisible Debate Watch Guide Winning with Our Values We Can Win in 2020

INDIVISIBLE DEBATE WATCH GUIDE WINNING WITH OUR VALUES WE CAN WIN IN 2020 Before we dive into the details of the crowded 2020 field, and what issues we think are most important to keep in mind as we evaluate that field, we wanted to be explicit: we can win in 2020. The 2016 election cycle was difficult and damaging in many ways, but one of the most lasting challenges is that it left so many of us scared. In 2018, we elected the most diverse Congress in our country’s history, made up of members who’ve sponsored bills like the Green New Deal and the sweeping democracy reforms in HR 1. But, as we look ahead to 2020, so many of us are still hung up on “electability.” Too often, we’re being guided by our fears, not our hopes, about the future of our country. As we head into 2020, we have a historically strong and diverse Democratic field. We have candidates who are unafraid to take bold positions on unrigging our democracy, creating a people-first immigration policy, and leaning into ambitious plans to address climate change. And we have candidates from a wide range of backgrounds: current US Senators, mayors of large and small cities, and two former members of the Obama administration. For the first time in our country’s history, we have a field that includes Latino, Black, white and AAPI candidates; gay and straight candidates; and working class candidates who are rejecting corporate PAC money. We know the stakes are high. But we think concerns about “electability” are a self-fulfilling prophecy.