Michelangelo and the Laurentian Library Cammy Brothers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

75. Sistine Chapel Ceiling and Altar Wall Frescoes Vatican City, Italy

75. Sistine Chapel ceiling and altar wall frescoes Vatican City, Italy. Michelangelo. Ceiling frescoes: c. 1508-1510 C.E Altar frescoes: c. 1536-1541 C.E., Fresco (4 images) Video on Khan Academy Cornerstone of High Renaissance art Named for Pope Sixtus IV, commissioned by Pope Julius II Purpose: papal conclaves an many important services The Last Judgment, ceiling: Book of Genesis scenes Other art by Botticelli, others and tapestries by Raphael allowed Michelangelo to fully demonstrate his skill in creating a huge variety of poses for the human figure, and have provided an enormously influential pattern book of models for other artists ever since. Coincided with the rebuilding of St. Peters Basilica – potent symbol of papal power Original ceiling was much like the Arena Chapel – blue with stars The pope insisted that Michelangelo (primarily a sculpture) take on the commission Michelangelo negotiated to ‘do what he liked’ (debateable) 343 figures, 4 years to complete inspired by the reading of scriptures – not established traditions of sacred art designed his own scaffolding myth: painted while lying on his back. Truth: he painted standing up method: fresco . had to be restarted because of a problem with mold o a new formula created by one of his assistants resisted mold and created a new Italian building tradition o new plaster laid down every day – edges called giornate o confident – he drew directly onto the plaster or from a ‘grid’ o he drew on all the “finest workshop methods and best innovations” his assistant/biographer: the ceiling is "unfinished", that its unveiling occurred before it could be reworked with gold leaf and vivid blue lapis lazuli as was customary with frescoes and in order to better link the ceiling with the walls below it which were highlighted with a great deal of gold’ symbolism: Christian ideals, Renaissance humanism, classical literature, and philosophies of Plato, etc. -

Michelangelo's Medici Chapel May Contain Hidden Symbols of Female Anatomy 4 April 2017

Michelangelo's Medici Chapel may contain hidden symbols of female anatomy 4 April 2017 "This study provides a previously unavailable interpretation of one of Michelangelo's major works, and will certainly interest those who are passionate about the history of anatomy," said Dr. Deivis de Campos, lead author of the Clinical Anatomy article. Another recent analysis by Dr. de Campos and his colleagues revealed similar hidden symbols in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. More information: Deivis de Campos et al, Pagan symbols associated with the female anatomy in the Medici Chapel by Michelangelo Buonarroti, Clinical Anatomy (2017). DOI: 10.1002/ca.22882 Highlight showing the sides of the tombs containing the bull/ram skulls, spheres/circles linked by cords and the shell (A). Note the similarity of the skull and horns to the Provided by Wiley uterus and fallopian tubes, respectively (B). The shell contained in image A clearly resembles the shell contained in Sandro Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" (1483), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy (C). Image B of the uterus and adnexa from Netter's Atlas of Human Anatomy with permission Philadelphia: Elsevier. Credit: Clinical Anatomy Michelangelo often surreptitiously inserted pagan symbols into his works of art, many of them possibly associated with anatomical representations. A new analysis suggests that Michelangelo may have concealed symbols associated with female anatomy within his famous work in the Medici Chapel. For example, the sides of tombs in the chapel depict bull/ram skulls and horns with similarity to the uterus and fallopian tubes, respectively. Numerous studies have offered interpretations of the link between anatomical figures and hidden symbols in works of art not only by Michelangelo but also by other Renaissance artists. -

Sponsor-A-Michelangelo Works Are Reserved in the Order That Gifts Are Received

Sponsor-A-Michelangelo Works are reserved in the order that gifts are received. Please call 615.744.3341 to make your selection. Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane, Masterpiece Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti October 30, 2015–January 6, 2016 Michelangelo Buonarroti. Man with Crested Helmet, ca. 1504. Pen and ink, 75 Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for a x 56 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. Draped Figure, ca. 1506. Pen and ink over 59F black chalk, 297 x 197 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 39F Sponsored by: Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the Leg of the Christ Child in the “Doni Sponsored by: Tondo,” ca. 1506. Pen and ink, 163 x 92 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 23F Sponsored by: Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the Apostles in the Transfiguration (Three Nudes), ca. 1532. Black chalk, pen and Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the ink. 178 x 209 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for Christ Head of the Madonna in the “Doni Florence, inv. 38F Tondo,” ca. 1506. Red chalk, 200 x 172 in Limbo, ca. 1532–33. Red chalk over black chalk. 163 x 149 mm. Casa mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 1F Sponsored by: Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 35F Reserved Sponsored by: Sponsored by: Patricia and Rodes Hart Michelangelo Buonarroti. The Sacrifice of Isaac, ca. 1535. Black chalk, red chalk, pen and ink. 482 x 298 mm. Casa Michelangelo Buonarroti. Studies of a Horse, ca. 1540. Black chalk, traces of red Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 70F chalk. 403 x 257 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Risen Christ, ca. 1532. Black chalk. 331 x 198 mm. -

The Art of Italy June 5Th -26Th

The IPFW Department of Fine Arts 2016 Study Abroad Program The Art of Italy June 5th -26th In our 14th year of Study Abroad travel, the IPFW Department of Fine Arts is excited to an- nounce its 2016 program, The Art of Italy. After flying to Rome, we will tour the city that is home to such wonders as the Colosseum and Forum, the Vatican Museum with its Sistine Chapel, and the Borghese Palace, full of beautiful sculptures by Bernini and paintings by Caravaggio. Outside of Rome, we will visit the ancient Roman site of Ostia Antica; on an- other day we will journey to the unique hill town of Orvieto, site of one of the most beautiful cathedrals in Italy and the evocative frescos of Luca Signorelli. We will next stay in Venice, one of the most unique cities in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage site. While there, we will tour the Doge’s Palace and the Academia Museum which displays paintings by such masters as Veronese and Giorgione. From Venice we will travel to Padua and view the ground breaking frescos of Giotto in the Arena Chapel as well as visit the pilgrimage church of Saint Anthony. Lastly, while residing in Florence, travelers will understand why this city was the epicenter of the Italian Renaissance. Art venues will include the Uffizi The beautiful Doge’s Palace and St. Mark’s Bell Tower seen Museum holding paintings such as Botticelli’s Birth of from the lagoon of Venice. Venus, the Academia Museum with Michelangelo’s David, and the impressive Pitti Palace and Gardens. -

Insider's Florence

Insider’s Florence Explore the birthplace of the Renaissance November 8 - 15, 2014 Book Today! SmithsonianJourneys.org • 1.877.338.8687 Insider’s Florence Overview Florence is a wealth of Renaissance treasures, yet many of its riches elude all but the most experienced travelers. During this exclusive tour, Smithsonian Journey’s Resident Expert and popular art historian Elaine Ruffolo takes you behind the scenes to discover the city’s hidden gems. You’ll enjoy special access at some of Florence’s most celebrated sites during private after-hours visits and gain insight from local experts, curators, and museum directors. Learn about restoration issues with a conservator in the Uffizi’s lab, take tea with a principessa after a private viewing of her art collection, and meet with artisans practicing their ages-old art forms. During a special day in the countryside, you’ll also go behind the scenes to explore lovely villas and gardens once owned by members of the Medici family. Plus, enjoy time on your own to explore the city’s remarkable piazzas, restaurants, and other museums. This distinctive journey offers first time and returning visitors a chance to delve deeper into the arts and treasures of Florence. Smithsonian Expert Elaine Ruffolo November 8 - 15, 2014 For popular leader Elaine Ruffolo, Florence offers boundless opportunities to study and share the finest artistic achievements of the Renaissance. Having made her home in this splendid city, she serves as Resident Director for the Smithsonian’s popular Florence programs. She holds a Master’s degree in art history from Syracuse University and serves as a lecturer and field trip coordinator for the Syracuse University’s program in Italy. -

The Press Release

Williamsburg, Muscarelle Museum of Art, February 6 –April 14, 2013 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, April 21--June 30, 2013 For Immediate Release 21 September 2012 To download images, please go to: http://www.wm.edu/muscarelle/michelangelopress.html MEDIA CONTACT: Betsy Moss for Muscarelle Museum of Art Phone: 804.355.1557 E-mail: [email protected] MICHELANGELO SCHOLAR AT MUSCARELLE MUSEUM TO ANNOUNCE MAJOR DRAWINGS SHOW PINA RAGIONIERI, DIRECTOR OF CASA BUONAROTTI, WILL GIVE ILLUSTRATED LECTURE OF MASTERPIECE DRAWINGS BY MICHELANGELO Twenty-six drawings in all media make Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane the most important Michelangelo show seen in the USA in decades. The Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William & Mary announced today that renowned Michelangelo scholar, Pina Ragionieri, will speak at the museum at 6:00 PM on September 25, 2012, to describe and illustrate the twenty-six original drawings by Michelangelo that will be in the major international exhibition, Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane Masterpiece Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti, opening February 9, 2013. The landmark exhibition is being organized in honor of the thirtieth anniversary of the foundation of the Muscarelle Museum of Art in 1983. Dr Pina Ragionieri, director of the Casa Buonarroti museum in Florence, will also attend the opening ceremonies and will be honored for her contributions to the studies of the great master. “I greatly look forward to this opportunity to display the treasures of the Casa Buonarroti at the Muscarelle Museum at the College of William & Mary,” she said. “International exhibitions introduce our museum not only to the specialists, but also to a broader public overseas.” Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane Masterpiece Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti, follows on the success of the 2010 exhibition at the Muscarelle, Michelangelo: Anatomy as Architecture, Drawings by the Master. -

500 Years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel

Petr Barenboim, Arthur Heath 500 YEARS OF THE NEW SACRISTY MICHEL 500 YEARS OF THE NEW SACRIST NEW THE OF YEARS 500 P etr Bar etr enboim ANGEL ( with Arthur Heath) Arthur with O IN THE MEDICI CHAPEL MEDICI THE IN O Y: The Moscow Florentine Society Petr Barenboim (with Arthur Heath) 500 YEARS OF THE NEW SACRISTY: MICHELANGELO IN THE MEDICI CHAPEL Moscow LOOM 2019 ISBN 978-5-906072-42-9 Illustrations: Photo by Sergei Shiyan 2-29,31-35, 45, 53-54; Photomontage by Alexander Zakharov 41; Wikimedia 1, 30, 35-36, 38-40, 42-44, 46-48, 50-52,57-60; The Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow 55-56 Cover design and composition Maria Mironova Barenboim Petr, Heath Arthur 500 years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel. Moscow, LOOM, 2019. — 152 p. ISBN 978-5-906072-42-9 Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) сriticism and interpretation. San Lorenzo Church (Florence, Italy) — Sagrestia Nuova, Medici. Dedicated to Professor Edith Balas In Lieu of a Preface: The Captive Spirit1 by Pavel Muratov (1881– 1950) Un pur esprit s’accroît sous l’écorce des pierres. Gerard de Nerval, Vers dores2 In the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo, in front of the Mi- chelangelo tombs, one can experience the most pure and fiery touch of art that a human being ever has the opportunity to ex- perience. All the forces with which art affects the human soul have become united here: the importance and depth of the con- ception, the genius of imagination, the grandeur of the images, and the perfection of execution. -

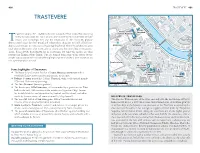

Trastevere (Map P. 702, A3–B4) Is the Area Across the Tiber

400 TRASTEVERE 401 TRASTEVERE rastevere (map p. 702, A3–B4) is the area across the Tiber (trans Tiberim), lying below the Janiculum hill. Since ancient times there have been numerous artisans’ Thouses and workshops here and the inhabitants of this essentially popular district were known for their proud and independent character. It is still a distinctive district and remains in some ways a local neighbourhood, where the inhabitants greet each other in the streets, chat in the cafés or simply pass the time of day in the grocery shops. It has always been known for its restaurants but today the menus are often provided in English before Italian. Cars are banned from some of the streets by the simple (but unobtrusive) method of laying large travertine blocks at their entrances, so it is a pleasant place to stroll. Some highlights of Trastevere ª The beautiful and ancient basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere with a wonderful 12th-century interior and mosaics in the apse; ª Palazzo Corsini, part of the Gallerie Nazionali, with a collection of mainly 17th- and 18th-century paintings; ª The Orto Botanico (botanic gardens); ª The Renaissance Villa Farnesina, still surrounded by a garden on the Tiber, built in the early 16th century as the residence of Agostino Chigi, famous for its delightful frescoed decoration by Raphael and his school, and other works by Sienese artists, all commissioned by Chigi himself; HISTORY OF TRASTEVERE ª The peaceful church of San Crisogono, with a venerable interior and This was the ‘Etruscan side’ of the river, and only after the destruction of Veii by remains of the original early church beneath it; Rome in 396 bc (see p. -

Florence Celebrates the Uffizi the Medici Were Acquisitive, but the Last of the Line Was Generous

ArtNews December 1982 Florence Celebrates The Uffizi The Medici were acquisitive, but the last of the line was generous. She left all the family’s treasures to the people of Florence. by Milton Gendel Whenever I vist The Uffizi Gallery, I start with Raphael’s classic portrait of Leo X and Two Cardinals, in which the artist shows his patron and friend as a princely pontiff at home in his study. The pope’s esthetic interests are indicated by the finely worked silver bell on the red-draped table and an illuminated Bible, which he has been studying with the aid of a gold-mounted lens. The brass ball finial on his chair alludes to the Medici armorial device, for Leo X was Giovanni de’ Medici, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Clutching the chair, as if affirming the reality of nepotism, is the pope’s cousin, Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi. On the left is Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, another cousin, whose look of reverie might be read, I imagine, as foreseeing his own disastrous reign as Pope Clement VII. That was five years in the future, of course, and could not have been anticipated by Raphael, but Leo had also made cardinals of his three nephews, so it wasn’t unlikely that another member of the family would be elected to the papacy. In fact, between 1513 and 1605, four Medici popes reigned in Rome. Leo X was a true Renaissance prince, whose civility and love of the arts impressed everyone - in the tradition of his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent. -

Michelangelo Buonarotti

MICHELANGELO BUONAROTTI Portrait of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra COMPILED BY HOWIE BAUM Portrait of Michelangelo at the time when he was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. by Marcello Venusti Hi, my name is Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, but you can call me Michelangelo for short. MICHAELANGO’S BIRTH AND YOUTH Michelangelo was born to Leonardo di Buonarrota and Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, a middle- class family of bankers in the small village of Caprese, in Tuscany, Italy. He was the 2nd of five brothers. For several generations, his Father’s family had been small-scale bankers in Florence, Italy but the bank failed, and his father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, briefly took a government post in Caprese. Michelangelo was born in this beautiful stone home, in March 6,1475 (546 years ago) and it is now a museum about him. Once Michelangelo became famous because of his beautiful sculptures, paintings, and poetry, the town of Caprese was named Caprese Michelangelo, which it is still named today. HIS GROWING UP YEARS BETWEEN 6 AND 13 His mother's unfortunate and prolonged illness forced his father to place his son in the care of his nanny. The nanny's husband was a stonecutter, working in his own father's marble quarry. In 1481, when Michelangelo was six years old, his mother died yet he continued to live with the pair until he was 13 years old. As a child, he was always surrounded by chisels and stone. He joked that this was why he loved to sculpt in marble.