Geographic Variation in the Gray Kingbird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Checklist Guánica Biosphere Reserve Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer Forest Service Research & Development Southern Research Station Research Note SRS-23 The Authors: Wayne J. Arendt, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station, HC 2 Box 6205, Luquillo, PR 00773, USA; John Faaborg, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211-7400, USA; Miguel Canals, DRNA—Bosque de Guánica, P.O. Box 1185, Guánica, PR 00653-1185, USA; and Jerry Bauer, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Río Piedras, PR 00926, USA. Cover Photos Large cover photograph by Jerry Bauer; small cover photographs by Mike Morel. Product Disclaimer The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service. April 2015 Southern Research Station 200 W.T. Weaver Blvd. Asheville, NC 28804 www.srs.fs.usda.gov BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer ABSTRACt This research note compiles 43 years of research and monitoring data to produce the first comprehensive checklist of the dry forest avian community found within the Guánica Biosphere Reserve. We provide an overview of the reserve along with sighting locales, a list of 185 birds with their resident status and abundance, and a list of the available bird habitats. Photographs of habitats and some of the bird species are included. -

Louisiana Bird Records Committee

LOUISIANA BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE REPORT FORM 1. English and Scientific names: Gray Kingbird, Tyrannus dominicensis 2. Number of individuals, sexes, ages, general plumage (e.g., 2 in alternate plumage): 1 3. Locality: Parish: __Terrebonne__________________________________________ Specific Locality: ___Trinity Island________________________________________ 4. Date(s) when observed: 5 June 2014 5. Time(s) of day when observed: 1125-1135 CDT 6. Reporting observer and address: Robert C. Dobbs, Lafayette, LA 7. Other observers accompanying reporter who also identified the bird(s): 8. Other observers who independently identified the bird(s): 9. Light conditions (position of bird in relation to shade and to direction and amount of light): Bright sunlight; no shade 10. Optical equipment (type, power, condition): Swarovski 8x30 binos 11. Distance to bird(s): 100 m 12. Duration of observation: 10 min 13. Habitat: spoil bank veg on barrier island 14. Behavior of bird / circumstances of observation (flying, feeding, resting; include and stress habits used in identification; relate events surrounding observation): Perched on exposed branch in crown of small tree; sallying for aerial insects 15. Description (include only what was actually seen, not what "should" have been seen; include if possible: total length/relative size compared to other familiar species, body bulk, shape, proportions, bill, eye, leg, and plumage characteristics. Stress features that separate it from similar species): Kingbird shape/size; gray head with dark mask, gray back and upperwings; whitish breast/belly; large (long/thick) bill; notched tail. 16. Voice: Not vocal 17. Similar species (include how they were eliminated by your observation): Eastern Kingbird (also present – direct comparison) has smaller bill, black crown and auriculars (no mask), blacker back and upper-wings, and black tail with white terminal band. -

Cuba's Western Mountains, Zapata Peninsula, Northern Archipelago

Cuba’s Western Mountains, Zapata Peninsula, Northern Archipelago, Escambray Valley and Havana Spring Migration Cuba Bird Survey April 1 – 11/12, 2017 You are invited on an exclusive, U.S. led and managed birding program to Cuba! The program is managed by the Caribbean Conservation Trust, Inc. (CCT), which is based in Connecticut. In early 2016 CCT staff began their 20th year of managing bird conservation and natural history programs in Cuba. Along with CCT Ornithologist Michael Good, our team will include award -winning Cuban biologist Ernesto Reyes, a bilingual Cuban tour leader and local naturalists in 4 different birding regions. They will guide you through some of the best bird habitat in Cuba, the Caribbean’s largest and most ecologically diverse island nation. CCT designed this itinerary to take you to Cuba’s finest bird habitats, most beautiful national parks, diverse biosphere reserves, and unique natural areas. We will interact with local scientists and naturalists who work in research and conservation. In addition to birding, we will learn about the ecology and history of regions we visit. Finally, and especially given the ongoing changes in U.S. – Cuban relations, we can expect some degree of inquiry into fascinating aspects of Cuban culture, history, and daily living during our visit. Cuba’s Birds According to BirdLife International, which has designated 28 Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in Cuba, “Over 370 bird species have been recorded in Cuba, including 27 which are endemic to the island and 29 considered globally threatened. Due to its large land area and geographical position within the Caribbean, Cuba represents one of the most important countries for Neotropical migratory birds – both birds passing through on their way south (75 species) and those spending the winter on the island (86 species).“ Our itinerary provides opportunities to see many of Cuba’s endemic species and subspecies, as listed below. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Dcb Good Bird Guide

, ABACO BIRD RECORD, commenced Feb 2010 (Page references are to Bruce Hallett’s ‘Birds of the Bahamas’ in the library) A QUICK GUIDE TO SOME OF THE BIRDLIFE AT DCB AND ELSEWHERE ON ABACO (Page references are to Bruce Hallett’s ‘Birds of the Bahamas’ in the library) The main identifications are as certain as an amateur (me) might wish - mostly by sight and sound (with the help of Hallett’s book), some by photo for later ID, some simply by being told. Some IDs are qualified in the comments – e.g. too many heron / egret / plover types and colourings to be sure which. Apologies to any proper ornithologists – feel free to correct or add / subtract info. KS Feb 2010 SPECIES LOCATION COMMENT PAGE ID / DATE IMAGE Bananaquit DCB That small chirpy thing that is so hard to see in 199 KS/Feb 10 the bushes… Western Spindalis [Tanager] DCB In trees along the drive (Hallett’s cover bird) 200 KS/Feb 10 (aka Bahama Finch) Cuban Emerald Hummingbird DCB Often seen in bushes below pool – and 143 KS/Feb 10 thankfully outside Room 1 Bahama Woodstar Hole-in-the-Wall Rare where Cuban Emeralds are. Trip not for 145 KS/Feb 10 Hummingbird faint-hearted – 30 miles return on rough track. It gradually gets worse (totally unsuitable for car). Photo of female; males have purple throat Turkey Vulture DCB / Ubiquitous Ever-present, sometimes wheeling around over 119 KS/Feb 10 the bay in flocks of 20 or so. Graceful in flight, less glamorous close up White-Tailed Tropicbird Sandy Point Seen flying with Frigatebirds 39 KS/Feb 10 Magnificent Frigatebird DCB / Sandy Point -

Bahamas: Abaco, Eleuthera, Andros and the Kirtland's Warbler 2015

Field Guides Tour Report Bahamas: Abaco, Eleuthera, Andros and the Kirtland's Warbler 2015 Apr 4, 2014 to Apr 9, 2015 Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Bahama Woodstar (Photo by participant Doug Hanna) This was another enjoyable island-hopping adventure with a fun group, excellent birding, and delicious food. It all started on the island of Abaco with a visit to Abaco Island National Park and our first Cuban Parrots perched in the pine trees and a Bahama Yellowthroat skulking in the understory. Bahama Palm Shores was also very good for parrots and West Indian Woodpecker, but lunch at Pete's Pub and "sittin' on the dock of the bay" in Cherokee Sound were also memorable. On to Eleuthera via our trusty Caravan, and within an hour we were looking at a pair of Kirtland's Warblers and our first Great Lizard-Cuckoo -- not too bad. But, again, lunch at Tippy's looking at quite possibly the prettiest beach in the world may have stolen the show, though we really enjoyed watching the sunset at The Cove! This was also the first year we offered a visit to Andros in search of the Bahama Oriole, a recent split from Greater Antillean Oriole. That turned out to be no problem, and we found its nest in the process. Turns out our group thought the Great Lizard-Cuckoo was the coolest thing since sliced bread, and I agree. It took home top honors, but it was in good company with Bahama Woodstar (female on the nest or maybe the male on Eleuthera?), and those parrots. -

Cuba Caribbean Endemic Birding VIII 3Rd to 12Th March 2017 (10 Days) Trip Report

Cuba Caribbean Endemic Birding VIII 3rd to 12th March 2017 (10 days) Trip Report Bee Hummingbird by Forrest Rowland Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader, Forrest Rowland Tour Participants: Alan Baratz, Ron and Cheryl Farmer, Cassia Gallagher, George Kenyon, Steve Nanz, Clive Prior, Heidi Steiner, Lucy Waskell, and Janet Zinn Trip Report – RBL Cuba - Caribbean Endemic Birding VIII 2017 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Tour Top Ten List: 1. Bee Hummingbird 6. Blue-headed Quail-Dove 2. Cuban Tody 7. Great Lizard Cuckoo 3. Cuban Trogon 8. Cuban Nightjar 4. Zapata Wren 9. Western Spindalis 5. Cuban Green Woodpecker 10. Gundlach’s Hawk ___________________________________________________________________________________ Tour Summary As any tour to Cuba does, we started by meeting up in fascinating Havana, where the drive from the airport to the luxurious (relatively, for Cuba) 5th Avenue Four Points Sheraton Hotel offers up more interesting sights than about any other airport drive I can think of. Passing oxcarts, Tractors hauling cane, and numerous old cars in various states of maintenance and care, participants made their way to one of the two Hotels in Cuba recently affiliated with larger world chain operations. While this might seem to be a bit of an odd juxtaposition to the indigenous parochial surroundings, the locals seem very excited to have the recent influx of foreign interest and monies to update and improve the local infrastructure, including this fine hotel. With the Russian embassy building dominating the skyline (a bizarre, monolithic, imposing structure indeed!) from our balconies, and the Caribbean on the horizon, we enjoyed the best Western Spindalis by Dušan Brinkhuizen accommodations in the city. -

Habitat Distribution of Birds Wintering in Central Andros, the Bahamas: Implications for Management

Caribbean Journal of Science, Vol. 41, No. 1, 75-87, 2005 Copyright 2005 College of Arts and Sciences University of Puerto Rico, Mayagu¨ez Habitat Distribution of Birds Wintering in Central Andros, The Bahamas: Implications for Management DAVE CURRIE1,JOSEPH M. WUNDERLE JR.2,5,DAVID N. EWERT3,MATTHEW R. ANDERSON2, ANCILLENO DAVIS4, AND JASMINE TURNER4 1 Puerto Rico Conservation Foundation c/o International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station HC 0 Box 6205, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773, USA. 2 International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station HC 0 Box 6205, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773, USA. 3 The Nature Conservancy, 101 East Grand River, Lansing, MI 48906, USA. 4 The Bahamas National Trust, P.O. Box N-4105, Nassau, The Bahamas. 5 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—We studied winter avian distribution in three representative pine-dominated habitats and three broadleaf habitats in an area recently designated as a National Park on Andros Island, The Bahamas, 1-23 February 2002. During 180 five-minute point counts, 1731 individuals were detected (1427 permanent residents and 304 winter residents) representing 51 species (29 permanent and 22 winter residents). Wood warblers (Family Parulidae) comprised the majority (81%) of winter residents. Total number of species and individuals (both winter and permanent residents) were generally highest in moderately disturbed pine- dominated habitats. The composition of winter bird communities differed between pine and broadleaf habitats; the extent of these differences was dependent broadleaf on composition and age in the pine understory. Fifteen bird species (nine permanent residents and six winter residents) exhibited significant habitat preferences. -

Species Table and Recommended Band Sizes the Table on the Left Is from the USGS Bird Banding Laboratory

Species Table and Recommended Band Sizes The table on the left is from the USGS Bird Banding Laboratory. If there is more than one size listed then the first one is the preferred recommended size. The table on the right may be used to find the National Band & Tag Company butt-end band style that matches the federal band size you are looking for. This Size Chart should be used as a guide only! We cannot be responsible for incorrect sizes being ordered based on this chart. Please measure your bird’s leg for accurate sizing, if you are unsure we will gladly send samples. Common Federal Federal NB&T Inside Inside Name Band Size Size Size Dia. (IN) Dia. (MM) Abert's Towhee 1A, 2, 1D 0A None .078 1.98 Acadian Flycatcher 0A, 0 0 None .083 2.11 Acorn Woodpecker 2, 3 1 1242-3 .094 2.39 Adelaide's Warbler 0A, 0 1B None .109 2.77 Adelie Penguin 9 1P None .112 2.84 African Collared-Dove 3A 1A 1242-4 .125 3.17 African Penguin 9 1D None .138 3.50 African Silverbill 0, 1C, 1 2 1242-5 .156 3.96 Akekee 1B, 1C, 1 3 1242-6 .188 4.78 Akepa 0 3B None .203 5.16 Akiapolaau 1A 3A 1242-7 .219 5.56 Akikiki 0, 1C, 1 4 1242-8 .250 6.35 Akohekohe 1A 4S 1242-8 .250 6.35 Alaska Marbled Murrelet 3B, 3 4A None .281 7.14 Alder Flycatcher 0, 0A 4AS None .281 7.14 Aleutian Canada Goose 7B 5 1242-10 .313 7.95 Aleutian Tern 2, 1A, 1D 5A None .344 8.73 Allen's Hummingbird X 6 1242-12 .375 9.53 Altamira Oriole 3 7A 1242-14 .438 11.13 American Avocet 4, 4A 7AS 1242-14 .438 11.13 American Bittern M: 7A F: 6 7 1242-16 .500 12.70 American Black Duck 7A 7B None .531 13.49 American -

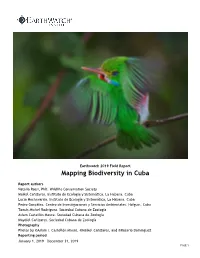

Mapping Biodiversity in Cuba

Earthwatch 2019 Field Report Mapping Biodiversity in Cuba Report authors Natalia Rossi, PhD. Wildlife Conservation Society Maikel Cañizares. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana. Cuba Lucia Hechavarria. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana. Cuba Pedro González. Centro de Investigaciones y Servicios Ambientales. Holguín. Cuba Tomás Michel Rodríguez. Sociedad Cubana de Zoología Aslam Castellón Maure. Sociedad Cubana de Zoología Maydiel Cañizares. Sociedad Cubana de Zoología Photography Photos by ©Aslam I. Castellón Maure, ©Maikel Cañizares, and ©Rosario Dominguez Reporting period January 1, 2019 – December 31, 2019 PAGE 1 LETTER TO VOLUNTEERS Dear Earthwatch volunteers, As we embark into our 2020 Earthwatch field expeditions, we wanted to take the time to reflect on our collective efforts in 2019 and share some of our highlights. Thanks to your commitment, motivation, and insatiable curiosity we had an incredible 2019! Together, we continue to discover and protect the biodiversity of Lomas de Banao Ecological Reserve. During 2019, we continued to support the conservation of this Reserve’s outstanding biodiversity. With your help, we planted over 1000 trees of native species that will enrich the forest for generations to come. We recorded new species in Banao, including a critically endangered and endemic Anolis lizard who will now call Banao home. We deepened our understanding of the seasonal dynamics of birds in Banao looking into the behavioral adjustments of native birds when, all the sudden, have to cope with the influx of numerous winter migrants. We discovered that Cuban parakeets switched their nesting grounds into the northern side of the Reserve, and built and placed artificial nests to support Cuban trogons, pygmy owls and bare-legged owls in the reproduction season. -

Avian Distribution Along a Gradient of Urbanization in Northeastern Puerto Rico

Ecological Bulletins 54: 141–156, 2013 Avian distribution along a gradient of urbanization in northeastern Puerto Rico Edgar O. Vázquez Plass and Joseph M. Wunderle Jr We studied avian distribution along an urban to forest gradient in northeastern Puerto Rico to document how dif- ferent species, species groups, and diet guilds respond to urbanization. Mean avian abundance and species richness sampled at 181 point count sites increased with urbanization and was associated with measures of developed habitat, pasture and elevation. Endemic species were sensitive to urbanization as evidenced by their negative association with an urbanization index, positive association with forest cover, and their rarity in urban habitat in contrast to their abundance and species richness in forest. Exotic species showed the opposite pattern by a positive association with an urbanization index and highest abundance and species-richness in suburban/urban habitats and absence from forest. Resident (non-endemic) species were found throughout the gradient, although species differed in the locations of peak abundance along the gradient. Resident species also displayed a positive association with the urbanization index and their abundance and species richness increased with urbanization. The increased avian abundance and species richness with urbanization was attributed to exotic granivores and omnivores and resident insectivores, granivores and omnivores. We hypothesize that availability of nearby undeveloped habitats may be critical for maintaining avian abundance and species richness in Puerto Rico’s urban areas, but emphasize that research is needed to test this hypothesis. E. O. Vázquez Plass ([email protected]), Dept of Biology, Univ. of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, PR 00931-3360, USA, present address: Dept of Natural Sciences, Univ. -

Cuba's Wild Western Peninsula, Western Mountains, Zapata

Cuba’s Wild Western Peninsula, Western Mountains, Zapata Peninsula, Northern Archipelago, and Havana Cuba Bird Survey November – 4 – 15/16 , 2017 You are invited on an exclusive, U.S. led and managed birding program to Cuba! The program is managed by the Caribbean Conservation Trust, Inc. (CCT), which is based in Connecticut. In early 2016 CCT staff began their 20th year of managing bird conservation and natural history programs in Cuba. Along with CCT Ornithologist Michael Good, our team will include award -winning Cuban biologist Ernesto Reyes, a bilingual Cuban tour leader and local naturalists in 4 different birding regions. They will guide you through some of the best bird habitat in Cuba, the Caribbean’s largest and most ecologically diverse island nation. CCT designed this itinerary to take you to Cuba’s finest bird habitats, most beautiful national parks, diverse biosphere reserves, and unique natural areas. We will interact with local scientists and naturalists who work in research and conservation. In addition to birding, we will learn about the ecology and history of regions we visit. Finally, and especially given the ongoing changes in U.S. – Cuban relations, we can expect some degree of inquiry into fascinating aspects of Cuban culture, history, and daily living during our visit. Cuba’s Birds According to BirdLife International, which has designated 28 Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in Cuba, “Over 370 bird species have been recorded in Cuba, including 26 which are endemic to the island and 29 considered globally threatened. Due to its large land area and geographical position within the Caribbean, Cuba represents one of the most important countries for Neotropical migratory birds – both birds passing through on their way south (75 species) and those spending the winter on the island (86 species).“ Our itinerary provides opportunities to see many of Cuba’s endemic species and subspecies, as listed below.