JCO 23(1) Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

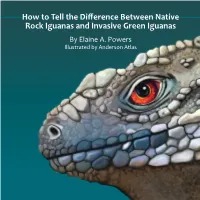

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Bird Checklist Guánica Biosphere Reserve Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer Forest Service Research & Development Southern Research Station Research Note SRS-23 The Authors: Wayne J. Arendt, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station, HC 2 Box 6205, Luquillo, PR 00773, USA; John Faaborg, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211-7400, USA; Miguel Canals, DRNA—Bosque de Guánica, P.O. Box 1185, Guánica, PR 00653-1185, USA; and Jerry Bauer, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Río Piedras, PR 00926, USA. Cover Photos Large cover photograph by Jerry Bauer; small cover photographs by Mike Morel. Product Disclaimer The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service. April 2015 Southern Research Station 200 W.T. Weaver Blvd. Asheville, NC 28804 www.srs.fs.usda.gov BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer ABSTRACt This research note compiles 43 years of research and monitoring data to produce the first comprehensive checklist of the dry forest avian community found within the Guánica Biosphere Reserve. We provide an overview of the reserve along with sighting locales, a list of 185 birds with their resident status and abundance, and a list of the available bird habitats. Photographs of habitats and some of the bird species are included. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge BIRD LIST

Merrritt Island National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service P.O. Box 2683 Titusville, FL 32781 http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Merritt_Island 321/861 0669 Visitor Center Merritt Island U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD National Wildlife Refuge March 2019 Bird List photo: James Lyon Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, located just Seasonal Occurrences east of Titusville, shares a common boundary with the SP - Spring - March, April, May John F. Kennedy Space Center. Its coastal location, SU - Summer - June, July, August tropic-like climate, and wide variety of habitat types FA - Fall - September, October, November contribute to Merritt Island’s diverse bird population. WN - Winter - December, January, February The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee lists 521 species of birds statewide. To date, 359 You may see some species outside the seasons indicated species have been identified on the refuge. on this checklist. This phenomenon is quite common for many birds. However, the checklist is designed to Of special interest are breeding populations of Bald indicate the general trend of migration and seasonal Eagles, Brown Pelicans, Roseate Spoonbills, Reddish abundance for each species and, therefore, does not Egrets, and Mottled Ducks. Spectacular migrations account for unusual occurrences. of passerine birds, especially warblers, occur during spring and fall. In winter tens of thousands of Abundance Designation waterfowl may be seen. Eight species of herons and C – Common - These birds are present in large egrets are commonly observed year-round. numbers, are widespread, and should be seen if you look in the correct habitat. Tips on Birding A good field guide and binoculars provide the basic U – Uncommon - These birds are present, but because tools useful in the observation and identification of of their low numbers, behavior, habitat, or distribution, birds. -

Local Companies Control Licenses

Org Name Lcl No T&B / Local Company Licence Start Date End Date Location File Number Description GRANT THORNTON SPECIALIST SERVICES 11/07 A Recovery And Reorganisation Practice Comprising The Provision Of Restructuring Advice Insolvency And 29-May-2007 29-May-2016 Block OPY Parcel 68/3, 2nd Floor Suite 4290, TB12650 Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) (CAYMAN) LIMITED Forensic Services 48 Market Street, George Town, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands MOORE STEPHENS DECOSIMO CAYMAN 32/05 Accountants 22-Nov-2005 22-Nov-2017 Block 12E, Parcel 106, Suite 200, Marquis TB9877 Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) LIMITED Place, West Bay, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands BDO CAYMAN LTD 07/11 Accounting And Auditing Services 29-Mar-2011 29-Mar-2023 23 Lime Tree Bay Avenue, Governor's Square, TB117AC Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) West Bay, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands SULA HOLDINGS LIMITED T/A BLUFF Agricultural Business Including Dairy Farming On Cayman Brac 24-Sep-2013 24-Sep-2025 Block 112A, Parcel 28, 30, 43, Cayman Brac, TB1095AB Agricultural production and Agrobased industries FARMS Cayman Islands JETBLUE AIRWAYS CORPORATION 07/12 Airline 04-Sep-2012 04-Sep-2024 Owen Roberts International Airport, 88C Owen TB705A Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) Roberts Drive, George Town, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands DELTA AIR LINES INC 09/11 Airline - Commercial Aircraft 26-Apr-2011 26-Apr-2023 Owen Roberts Airport, George Town, Grand TB6536 Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) Cayman US AIRWAYS INC 114311 Airline Agent 24-Aug-2010 24-Aug-2022 88C Owen Roberts Drive, George Town, Grand TB513A Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) Cayman, Cayman Islands RS&H INC. -

Panama Canal with Princess Cruises® on the Crown Princess® 11 Days / 10 Nights ~ March 23 – April 2, 2022

GRUNDY COUNTY SENIOR CENTER PRESENTS PANAMA CANAL WITH PRINCESS CRUISES® ON THE CROWN PRINCESS® 11 DAYS / 10 NIGHTS ~ MARCH 23 – APRIL 2, 2022 DAY PORT ARRIVE DEPART 1 Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 4:00 PM 2 At Sea 3 Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands 7:00 AM 5:00 PM 4 At Sea 5 Cartagena, Colombia 7:00 AM 3:00 PM 6 Panama Canal Partial Transit New Locks 6:00 AM 3:30 PM 6 Cristobal, Panama 4:00 PM 7:00 PM 7 Limon, Costa Rica 7:00 AM 6:00 PM 8 At Sea 9 Falmouth, Jamaica 7:00 AM 3:00 PM 10 At Sea 11 Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 7:00 AM IF YOU BOOK BY OCTOBER 29, 2021 Inside Cabin Category IC $2,695 ONLY $100 pp DEPOSIT REQUIRED Outside Cabin Category OC $3,160 FOR DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Balcony Cabin Category BC $3,515 After 10/29/21 deposit is at least $350 pp * subject to capacity control* Rates are per person double occupancy and include roundtrip airfare PRINCESS PLUS from Kansas City, cruise, port charges, government fees, taxes and transfers to/from ship. PRINCESS CRUIES® HAS ADVISED THAT ALL FREE Premier Beverage Package AIR PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND ARE NOT FREE Unlimited Wi-Fi GUARANTEED UNTIL FULL PAYMENT HAS BEEN RECEIVED. FREE Prepaid Gratuities Offer applies to all guests in cabin. PASSPORT REQUIRED Offer is capacity controlled and subject to change. Please call for details DEPOSIT POLICY: An initial deposit of $350 per person double occupancy or $700 per person single occupancy is required in order to secure reservations and assign cabins. -

Bird Checklist for St. Johns County Florida (As of January 2019)

Bird Checklist for St. Johns County Florida (as of January 2019) DUCKS, GEESE, AND SWANS Mourning Dove Black-bellied Whistling-Duck CUCKOOS Snow Goose Yellow-billed Cuckoo Ross's Goose Black-billed Cuckoo Brant NIGHTJARS Canada Goose Common Nighthawk Mute Swan Chuck-will's-widow Tundra Swan Eastern Whip-poor-will Muscovy Duck SWIFTS Wood Duck Chimney Swift Blue-winged Teal HUMMINGBIRDS Cinnamon Teal Ruby-throated Hummingbird Northern Shoveler Rufous Hummingbird Gadwall RAILS, CRANES, and ALLIES American Wigeon King Rail Mallard Virginia Rail Mottled Duck Clapper Rail Northern Pintail Sora Green-winged Teal Common Gallinule Canvasback American Coot Redhead Purple Gallinule Ring-necked Duck Limpkin Greater Scaup Sandhill Crane Lesser Scaup Whooping Crane (2000) Common Eider SHOREBIRDS Surf Scoter Black-necked Stilt White-winged Scoter American Avocet Black Scoter American Oystercatcher Long-tailed Duck Black-bellied Plover Bufflehead American Golden-Plover Common Goldeneye Wilson's Plover Hooded Merganser Semipalmated Plover Red-breasted Merganser Piping Plover Ruddy Duck Killdeer GROUSE, QUAIL, and ALLIES Upland Sandpiper Northern Bobwhite Whimbrel Wild Turkey Long-billed Curlew GREBES Hudsonian Godwit Pied-billed Grebe Marbled Godwit Horned Grebe Ruddy Turnstone FLAMINGOS Red Knot American Flamingo (2004) Ruff PIGEONS and DOVES Stilt Sandpiper Rock Pigeon Sanderling Eurasian Collared-Dove Dunlin Common Ground-Dove Purple Sandpiper White-winged Dove Baird's Sandpiper St. Johns County is a special place for birds – celebrate it! Bird Checklist -

Louisiana Bird Records Committee

LOUISIANA BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE REPORT FORM 1. English and Scientific names: Gray Kingbird, Tyrannus dominicensis 2. Number of individuals, sexes, ages, general plumage (e.g., 2 in alternate plumage): 1 3. Locality: Parish: __Terrebonne__________________________________________ Specific Locality: ___Trinity Island________________________________________ 4. Date(s) when observed: 5 June 2014 5. Time(s) of day when observed: 1125-1135 CDT 6. Reporting observer and address: Robert C. Dobbs, Lafayette, LA 7. Other observers accompanying reporter who also identified the bird(s): 8. Other observers who independently identified the bird(s): 9. Light conditions (position of bird in relation to shade and to direction and amount of light): Bright sunlight; no shade 10. Optical equipment (type, power, condition): Swarovski 8x30 binos 11. Distance to bird(s): 100 m 12. Duration of observation: 10 min 13. Habitat: spoil bank veg on barrier island 14. Behavior of bird / circumstances of observation (flying, feeding, resting; include and stress habits used in identification; relate events surrounding observation): Perched on exposed branch in crown of small tree; sallying for aerial insects 15. Description (include only what was actually seen, not what "should" have been seen; include if possible: total length/relative size compared to other familiar species, body bulk, shape, proportions, bill, eye, leg, and plumage characteristics. Stress features that separate it from similar species): Kingbird shape/size; gray head with dark mask, gray back and upperwings; whitish breast/belly; large (long/thick) bill; notched tail. 16. Voice: Not vocal 17. Similar species (include how they were eliminated by your observation): Eastern Kingbird (also present – direct comparison) has smaller bill, black crown and auriculars (no mask), blacker back and upper-wings, and black tail with white terminal band. -

Cuba's Western Mountains, Zapata Peninsula, Northern Archipelago

Cuba’s Western Mountains, Zapata Peninsula, Northern Archipelago, Escambray Valley and Havana Spring Migration Cuba Bird Survey April 1 – 11/12, 2017 You are invited on an exclusive, U.S. led and managed birding program to Cuba! The program is managed by the Caribbean Conservation Trust, Inc. (CCT), which is based in Connecticut. In early 2016 CCT staff began their 20th year of managing bird conservation and natural history programs in Cuba. Along with CCT Ornithologist Michael Good, our team will include award -winning Cuban biologist Ernesto Reyes, a bilingual Cuban tour leader and local naturalists in 4 different birding regions. They will guide you through some of the best bird habitat in Cuba, the Caribbean’s largest and most ecologically diverse island nation. CCT designed this itinerary to take you to Cuba’s finest bird habitats, most beautiful national parks, diverse biosphere reserves, and unique natural areas. We will interact with local scientists and naturalists who work in research and conservation. In addition to birding, we will learn about the ecology and history of regions we visit. Finally, and especially given the ongoing changes in U.S. – Cuban relations, we can expect some degree of inquiry into fascinating aspects of Cuban culture, history, and daily living during our visit. Cuba’s Birds According to BirdLife International, which has designated 28 Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in Cuba, “Over 370 bird species have been recorded in Cuba, including 27 which are endemic to the island and 29 considered globally threatened. Due to its large land area and geographical position within the Caribbean, Cuba represents one of the most important countries for Neotropical migratory birds – both birds passing through on their way south (75 species) and those spending the winter on the island (86 species).“ Our itinerary provides opportunities to see many of Cuba’s endemic species and subspecies, as listed below. -

Recent Occurrences of Unusually Plumaged Kingbirds (Tyrannus) in Florida: Hybrids Or Little-Noticed Natural Variants?

Florida Field Naturalist 45(3):79-86, 2017. RECENT OCCURRENCES OF UNUSUALLY PLUMAGED KINGBIRDS (Tyrannus) IN FLORIDA: HYBRIDS OR LITTLE-NOTICED NATURAL VARIANTS? STU WILSON Sarasota, Florida Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION In the spring of 2016, two observers at two widely separated locations studied and photographed what appeared to be Gray Kingbirds (T. dominicensis) that had a highly unusual extensive yellow wash on the underparts. On 5 April 2016, experienced Florida birder Carl Goodrich (pers. comm.) noted an odd-looking kingbird on a wire in the company of two Gray Kingbirds at Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park (“Fort Zach”) at Key West, Monroe County, Florida. In his first view, without a binocular, the bird struck him as a Western Kingbird (T. verticalis) because of the yellow on the underparts. Later the same day, when he was able to photograph the bird and study it in more detail with a binocular, he realized it was not a Western Kingbird. Goodrich has seen “thousands of Gray Kingbirds in the Keys over the last 40 years and none were as yellow as this one” (Fig. 1A). He believes he saw the same bird a week earlier in a gumbo limbo (Bursera simaruba) at the same location in the company of a dozen Gray Kingbirds, but was not able to photograph it on that occasion. On 15 May 2016, Michelle Wilson (pers. comm.) was birding on Lust Road at Lake Apopka North Shore Restoration Area (LANSRA), Orange County, Florida, part of the Lake Apopka Wildlife Drive. There she photographed a kingbird (Fig. -

Early- to Mid-Succession Birds Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Early- to Mid-Succession Birds Guild Bewick's Wren Thryomanes bewickii Blue Grosbeak Guiraca caerulea Blue-winged Warbler Vermivora pinus Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum Chestnut-sided Warbler Dendroica pensylvanic Dickcissel Spiza americana Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus Golden-winged Warbler Vermivora chrysoptera Gray Kingbird Tyrannus dominicensis Indigo Bunting Passerina cyanea Orchard Oriole Icterus spurius Prairie Warbler Dendroica discolor White-eyed Vireo Vireo griseus Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Yellow-breasted Chat Icteria virens NOTE: The Yellow-billed Cuckoo is also discussed in the Deciduous Forest Interior Birds Guild. Contributors (2005): Elizabeth Ciuzio (KYDNR), Anna Huckabee Smith (NCWRC), and Dennis Forsythe (The Citadel) Reviewed and Edited: (2012) John Kilgo (USFS), Nick Wallover (SCDNR); (2013) Lisa Smith (SCDNR) and Anna Huckabee Smith (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description All bird species in this guild belong to the taxonomic order Passeriformes (perching birds) and they are grouped in 9 different families. The Blue-winged, Chestnut-sided, Golden-winged, and Prairie Warblers are in the family Parulidae (the wood warblers). The Eastern and Gray Kingbirds are in the flycatcher family, Tyrannidae. The Blue Grosbeak, Dickcissel, and Indigo Bunting are in the family Cardinalidae. The Bewick’s Wren is in the wren family, Troglodytidae. The orchard oriole belongs to the family Icteridae. The Brown Thrasher is in the family Mimidae, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo belongs to the family Cuculidae, the Eastern Towhee is in the family Emberizidae, and the White-eyed Vireo is in the family Vireonidae. All are small Blue-winged Warbler birds and can be distinguished by song, appearance, and habitat preference. -

Quaternary Bat Diversity in the Dominican Republic

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3779, 20 pp. June 21, 2013 Quaternary Bat Diversity in the Dominican Republic PAÚL M. VELAZCO,1 HANNAH O’NEILL,2 GREGG F. GUNNELL,3 SIOBHÁN B. COOKE,4 RENATO RIMOLI,5 ALFRED L. ROSENBErgER,1, 6 AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT The fossil record of bats is extensive in the Caribbean, but few fossils have previously been reported from the Dominican Republic. In this paper, we describe new collections of fossil bats from two flooded caves in the Dominican Republic, and summarize previous finds from the Island of Hispaniola. The new collections were evaluated in the context of extant and fossil faunas of the Greater Antilles to provide information on the evolution of the bat community of Hispaniola. Eleven species were identified within the new collections, including five mormoopids (Mormoops blainvillei, †Mormoops magna, Pteronotus macleayii, P. parnellii, and P. quadridens), five phyllostomids (Brachy- phylla nana, Monophyllus redmani, Phyllonycteris poeyi, Erophylla bombifrons, and Phyllops falcatus), and one natalid (Chilonatalus micropus). All of these species today inhabitant Hispaniola with the exception of †Mormoops magna, an extinct species previously known only from the Quaternary of Cuba, and Pteronotus macleayii, which is currently known only from extant populations in Cuba and Jamaica, although Quaternary fossils have also been recovered in the Bahamas. Differences between the fossil faunas and those known from the island today suggest that dispersal and extirpa- tion events, perhaps linked to climate change or stochastic events such as hurricanes, may have played roles in structuring the modern fauna of Hispaniola. 1 Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy), American Museum of Natural History. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies.