"Leviathan of Wealth": West Midland Agriculture, I8OO-50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lilleshall Open Forum ACTION PLANS Reviewed Against Survey.Xlsx

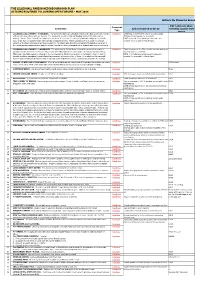

THE LILLESHALL PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN ACTIONS REQUIRED FOLLOWING OPEN FORUMS - MAY 2016 Actions By Planning Group RW Comments when Comment Comments Action Required by Group reviewing against draft Type survey 1 LILLESHALL ALLOTMENTS - SUBSIDIES. Few allotment holders are Lilleshall electors and a disproportionate number Land use LNPG Pass on comment to LPC to provide a policy of them have connections with our Council. The allotments should be fully self-funding and cost Lilleshall electors statement and response to comment. nothing. Yet the Parish Council has budgeted to run them at a loss for a second year, without having even costed the LNPG to include issue within questionnaire and many hours that our salaried Parish Clerk spends administering them. These subsidies are most unfair on Lilleshall consider for proposed for Plan Policies. electors as the main beneficiaries are Muxton electors. Allotment rents should be increased immediately to cover all of their costs including administration and this principle should be observed annually when budgets and rents are reviewed. 2 LILLESHALL ALLOTMENTS - OWNERSHIP. The allotments at Cheswell were funded by our previous council to Land use Pass on comment to LPC to provide a policy statement provide some 30 allotments for Muxton electors and 6 for Lilleshall electors. (Donnington already having allotments). and response to comment. While legal ownership passed to Lilleshall in the re-organization, Muxton has a strong moral claim to most of them. A LNPG to include issue within questionnaire and transfer should be considered, giving Lilleshall a permanent entitlement to six of them. It is ridiculous that our small consider for proposed for Plan Policies. -

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

S519 Shrewsbury - Newport Arriva Midlands Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions 1 1 Notes Sch Sch Shrewsbury, Bus Station (Stand L) 1445 1715 § Shrewsbury, opp Post Office 1447 1717 § Castle Fields, adj Gasworks 1448 1718 § Castle Fields, opp Social Services Offices 1449 1719 § Ditherington, adj Flax Mill 1451 1721 § Ditherington, adj The Coach 1452 1722 § Ditherington, adj Six Bells 1453 1723 Sundorne, adj The Heathgates 1455 1725 § Sundorne, adj Albert Road Junction 1455 1725 § Sundorne, adj Robsons Stores 1456 1726 § Sundorne, opp TA Centre 1456 1726 § Sundorne, opp Sports Village 1457 1727 Sundorne, adj Featherbed Lane Junction 1458 1728 § Uffington, opp Junction 1458 1728 § Uffington, adj Abbey 1501 1731 § Roden, adj Kennels 1505 1735 Roden, opp Nurseries 1507 1737 § Roden, before Hall 1507 1737 § Roden, adj Hall 1507 1737 § High Ercall, opp Talbot Fields 1511 1741 § High Ercall, opp Church Road 1512 1742 High Ercall, adj Cleveland Arms 1513 1743 § Cotwall, adj New Cottages 1514 1744 § Moortown, adj T Junction 1515 1745 § Crudgington, after Crossroads 1517 1747 § Crudgington, opp Manor Place 1518 1748 § Crudgington, opp Shray Hill Farm 1521 1751 Tibberton, nr Sutherland Arms 1528 1758 § Edgmond, adj Harper Adams University 1532 1802 § Edgmond, opp Longwithy Lane 1533 1803 § Edgmond, opp Lamb Inn 1534 1804 Edgmond, adj Lion Inn 1536 1806 § Edgmond, opp Robin Lane 1537 1807 § Edgmond, Newport Road (E-bound) 1538 1808 0 § Newport, opp Stone Bridge 1540 1810 § Newport, opp Green Lane 1541 1811 § Newport, opp Adams Grammar School 1542 1812 Newport, Bus Interchange (Stand A) 1546 1816 Saturdays no service Sundays no service Service Restrictions: 1 - to 17.12.21, not 25.10.21 to 29.10. -

Welcome to the Telford T50 50 Mile Trail

WELCOME TO THE TELFORD T50 50 MILE TRAIL This new 50 mile circular walking route was created in 2018 to celebrate Telford’s 50th anniversary as a New Town. It uses existing footpaths, tracks and quiet roads to form one continuous trail through the many different communities, beautiful green spaces and heritage sites that make Telford special. The Telford T50 50 Mile Trail showcases many local parks, nature reserves, woods, A 50 MILE TRAIL FOR EVERYONE TO ENJOY pools and open spaces. It features our history and rich industrial heritage. We expect people will want to explore this Fifty years ago, Telford’s Development Plan wonderful new route by starting from the set out to preserve a precious legacy of green space closest to where they live. green networks and heritage sites and allow old industrial areas to be reclaimed by wild The route is waymarked throughout with nature. This walk celebrates that vision of a magenta 'Telford 50th Anniversary' logo. interesting and very special places left for everyone to enjoy. The Trail was developed The Trail begins in Telford Town Park, goes by volunteers from Wellington Walkers are down to Coalport and Ironbridge then on Welcome, the Long Distance Walkers through Little Wenlock to The Wrekin, that Association, Walking for Health Telford & marvellous Shropshire landmark. It then Wrekin, Ironbridge Gorge Walking Festival continues over The Ercall nature reserve and Telford & East Shropshire Ramblers. through Wellington, Horsehay and Oakengates to Lilleshall, where you can www.telfordt5050miletrail.org.uk walk to Newport via The Hutchison Way. After Lilleshall it goes through more areas of important industrial heritage, Granville Country Park and back to The Town Centre. -

Election of a Borough Councillor for Church Aston & Lilleshall Notice Is Hereby Given That: 1

Telford & Wrekin Election of a Borough Councillor for Church Aston & Lilleshall Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Borough Councillor for Church Aston & Lilleshall will be held on Thursday 2 May 2A19, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Borough Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows. Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Froposers(+1. Seconders{++) & Assentors tAut (Address in Borough of The Conservative Party WilliamRDHarper(+) Malcolm D Gale {++; Andrew John Telford and Wrekin) Candidate Patricia H Richards Brian Richards David H Parker Roger D Evlyn-Bufton Tina J Price Elliot J Evlyn-Bufton Andrew D Baker Caroi A Baker ELLAMS Station Cottage, Liberal Democrats Christopher P Harper Kenneth W Broad (++) Dayid Arwyn Chetwynd Aston, (+) Doreen Eney Newport, TF10 9LL Raymond C Griffiths Carol M Evans David A Evans Wendy P Whittington Grahame T L Weir Holly A Davies Michael J Whittinqton SLOAN 5 Heatherdale, Apley, Labour Party Matthew Thursfield (+) Shelley A Thursfield Robert James Telford, TF1 6YW Carolyn Skifi (**) Donna Hesbrook- Christopher J Del- Edwards Manso Claire Femando Supul N Femando Helena R Wessels- DieterWessels Hartlev Judith Heath 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register Situation of Polling Station numbors of Number persons entitled to vote thereat Church Aston Village Hall, Wallshead Way, Church Aston, 43 WCA-I toWCA-941 Newoort Church Aston Village Hall, Wallshead Way, Church Aston, 43 WCC-I toWCC-283 Newoort Lilleshall Memorial Hall, Hillside. -

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

S521 Shrewsbury - Newport Arriva Midlands Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions 1 Notes Sch Shrewsbury, Bus Station (Stand L) 0735 § Shrewsbury, opp Post Office 0737 § Castle Fields, adj Gasworks 0738 § Castle Fields, opp Social Services Offices 0739 § Ditherington, adj Flax Mill 0739 § Ditherington, adj The Coach 0740 § Ditherington, adj Six Bells 0741 Sundorne, adj The Heathgates 0742 § Sundorne, adj Albert Road Junction 0742 § Sundorne, adj Robsons Stores 0743 § Sundorne, opp TA Centre 0743 § Sundorne, opp Sports Village 0744 Sundorne, adj Featherbed Lane Junction 0745 § Uffington, adj Abbey 0748 § Roden, adj Kennels 0751 Roden, opp Nurseries 0754 § Roden, adj Hall 0755 § High Ercall, opp Talbot Fields 0757 § High Ercall, opp Church Road 0758 High Ercall, adj Cleveland Arms 0800 § Cotwall, adj New Cottages 0801 § Crudgington, after Crossroads 0805 § Crudgington, opp Manor Place 0806 § Crudgington, opp Shray Hill Farm 0809 § Edgmond, adj Harper Adams University 0811 § Edgmond, opp Longwithy Lane 0812 § Edgmond, opp Lamb Inn 0813 Edgmond, opp Lamb Inn 0815 § Edgmond, opp Robin Lane 0816 § Edgmond, Newport Road (E-bound) 0817 § Newport, opp Stone Bridge 0819 § Newport, opp Green Lane 0821 § Newport, opp Adams Grammar School 0822 Newport, adj Boots 0824 0 § Newport, opp Police Station 0826 Newport, opp Girls High School 0830 Saturdays no service Sundays no service Service Restrictions: 1 - from 25.10.21, not 1.11.21 -

S519 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S519 bus time schedule & line map S519 Shrewsbury - Newport View In Website Mode The S519 bus line (Shrewsbury - Newport) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newport: 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM (2) Shrewsbury: 7:25 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S519 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S519 bus arriving. Direction: Newport S519 bus Time Schedule 38 stops Newport Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Bus Station, Shrewsbury Tuesday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Post O∆ce, Shrewsbury Wednesday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Gasworks, Castle Fields Thursday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Social Services O∆ces, Castle Fields Friday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM St Michael's Terrace, Shrewsbury Saturday Not Operational Flax Mill, Ditherington Spring Gardens, Shrewsbury The Coach Ph, Ditherington S519 bus Info Six Bells Ph, Ditherington Direction: Newport Stops: 38 The Heathgates Ph, Sundorne Trip Duration: 61 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Shrewsbury, Post O∆ce, Albert Road Jct, Sundorne Shrewsbury, Gasworks, Castle Fields, Social Services O∆ces, Castle Fields, Flax Mill, Ditherington, The Coach Ph, Ditherington, Six Bells Ph, Ditherington, Robsons Stores, Sundorne The Heathgates Ph, Sundorne, Albert Road Jct, Sundorne Road, Shrewsbury Sundorne, Robsons Stores, Sundorne, Ta Centre, Sundorne, Sports Village, Sundorne, Featherbed Ta Centre, Sundorne Lane Jct, Sundorne, Junction, U∆ngton, Abbey, U∆ngton, Kennels, Roden, Nurseries, Roden, Hall, Sports Village, Sundorne Roden, Hall, Roden, Talbot Fields, -

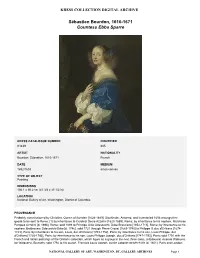

Summary for Countess Ebba Sparre

KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE Sébastien Bourdon, 1616-1671 Countess Ebba Sparre KRESS CATALOGUE NUMBER IDENTIFIER K1439 605 ARTIST NATIONALITY Bourdon, Sébastien, 1616-1671 French DATE MEDIUM 1652/1653 oil on canvas TYPE OF OBJECT Painting DIMENSIONS 106.1 x 90.2 cm (41 3/4 x 35 1/2 in) LOCATION National Gallery of Art, Washington, District of Columbia PROVENANCE Probably commissioned by Christina, Queen of Sweden [1626-1689], Stockholm, Antwerp, and inventoried 1656 amongst her goods to be sent to Rome; [1] by inheritance to Cardinal Decio Azzolini [1623-1689], Rome; by inheritance to his nephew, Marchese Pompeo Azzolini [d. 1696], Rome; sold 1696 to Principe Livio Odescalchi, Duke Bracciano [1652-1713], Rome; by inheritance to his nephew, Baldassare Odescalchi-Erba [d. 1746]; sold 1721 through Pierre Crozat [1665-1740] to Philippe II, duc d'Orléans [1674- 1723], Paris; by inheritance to his son, Louis, duc d'Orléans [1703-1752], Paris; by inheritance to his son, Louis Philippe, duc d'Orléans [1725-1785], Paris; by inheritance to his son, Louis Philippe Joseph, duc d'Orléans [1747-1793], Paris; sold 1791 with the French and Italian paintings of the Orléans collection, which figure as a group in the next three sales, to Edouard, vicomte Walkuers [or Walquers], Brussels; sold 1792 to his cousin, François Louis Joseph, comte Laborde de Méréville [d. 1801], Paris and London; NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 1 KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE on consignment until 1798 with (Jeremiah Harman, London); sold 1798 through (Michael Bryan, London) to a consortium of Francis Egerton, 3rd duke of Bridgewater [1736-1803], London and Worsley Hall, Lancashire, Frederick Howard, 5th earl of Carlisle [1748- 1825], Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, and George Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st duke of Sutherland [1758-1833], London, Trentham Hall, Stafford, and Dunrobin Castle, Highland, Scotland. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Lilleshall Parish Council the Memorial Hall, Hillside, Lilleshall, Shropshire, TF10 9HG

J3/60/2 Lilleshall Parish Council The Memorial Hall, Hillside, Lilleshall, Shropshire, TF10 9HG. Tel: 01952 676379 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir EXAMINATION OF THE TELFORD AND WREKIN LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 MATTERS, ISSUES & QUESTIONS PAPER Matter – 3 Question 3.2 Is the Local Plan’s settlement hierarchy and proposed distribution of development, particularly between the urban and rural areas, sufficiently justified? With reference to paragraph 28 of the Framework, is adequate provision made for development in rural settlements? I write on behalf of the Lilleshall Parish Council to confirm our support for the statement issued by the Parish & Town Council Group regarding Policy HO10 of the emerging Local Plan. We (the Parish Council) would like to supplement the statement by pointing out that the fundamental aspects of our rural communities are the built and natural environments which combine to provide the intrinsic quality of our landscape. This makes our rural communities what they are. It is therefore impossible to consider the distribution of sustainable development within the rural area, without consideration for the natural environment. The emerging Local Plan provides for sustainable development along with protection of our natural environment through the Policy HO10 in conjunction with the proposals included in Section 6 - Natural environment, where Policy NE7 - Strategic Landscapes is of particular importance. However, Question 6.2 of the Matters challenges the justification of Strategic Landscapes and their consistency with national policy in the Framework. We therefore wish to supplement the statement issued by Parish & Town Council Group with the following points for your consideration. The Lilleshall Parish Council supports the adoption of the Strategic Landscapes, and their purpose to protect the appearance and intrinsic quality of the designated areas. -

S5 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S5 bus time schedule & line map S5 Telford - Donnington - Newport - Stafford View In Website Mode The S5 bus line (Telford - Donnington - Newport - Stafford) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newport: 7:50 AM - 4:55 PM (2) Newport: 7:05 AM - 7:25 AM (3) Stafford Town Centre: 7:55 AM - 3:50 PM (4) Telford Town Centre: 3:32 PM - 4:02 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S5 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S5 bus arriving. Direction: Newport S5 bus Time Schedule 41 stops Newport Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Gaol Square, Stafford Town Centre North Walls, Stafford Tuesday Not Operational Chell Road, Stafford Town Centre Wednesday 7:50 AM - 4:55 PM Chell Road, Stafford Thursday Not Operational Railway Station, Stafford Town Centre Friday Not Operational Station Road, Stafford Saturday Not Operational Rowley Avenue, Stafford Deanshill Close, Stafford Oakbrook Close, Stafford S5 bus Info Eliot Way, Stafford Direction: Newport Stops: 41 Castle Church, Stafford Trip Duration: 36 min Line Summary: Gaol Square, Stafford Town Centre, Thorneyƒelds Lane, Stafford Chell Road, Stafford Town Centre, Railway Station, Stafford Town Centre, Rowley Avenue, Stafford, Sundown Drive, Stafford Deanshill Close, Stafford, Oakbrook Close, Stafford, Newport Road, England Castle Church, Stafford, Thorneyƒelds Lane, Stafford, Sundown Drive, Stafford, Derrington Lane, Derrington Lane, Billington Billington, Bury Road, Billington, Billington Hall, Billington, Bradley -

Final Draft Telford Wrekin Strategic Landscapes Study

Telford & Wrekin STRATEGIC LANDSCAPES STUDY Final Report December 2015 The Wrekin from Coalbrookdale, Shropshire by William Henry Gates (1854-1935) Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery , Reproduced with permission Fiona Fyfe Associates with Countryscape and Douglas Harman Landscape Planning Grasmere House, 39 Charlton Grove, Beeston, Nottinghamshire NG9 1GY www.fionafyfe.co.uk (0115) 8779139 [email protected] TELFORD & WREKIN STRATEGIC LANDSCAPES STUDY PART 1: INTRODUCTION Acknowledgements The author would like to thank all members of the project team for their excellent contributions to the project: Douglas Harman for sharing the fieldwork and contributing to the write-up, and Jonathan Porter of Countryscape for the GIS and cartography. Thanks are also due to the client team (specifically Lawrence Munyuki and Michael Vout of Telford & Wrekin Council) for sharing their knowledge, enthusiasm and advice throughout the project. All photographs in this document have been taken by Fiona Fyfe. 2 Final Report, December 2015 Fiona Fyfe Associates TELFORD & WREKIN STRATEGIC LANDSCAPES STUDY PART 1: INTRODUCTION Contents PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 Commissioning 7 1.2 Purpose 7 1.3 Format of study 7 1.4 Planning policy context 9 2.0 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 2.1 Current best practice guidance 11 2.2 Terminology 12 2.3 Green infrastructure and ecosystem services 12 2.4 Defining the extents of Strategic Landscapes 13 2.5 The Shropshire Landscape Typology 14 2.6 Stages of Work 15 PART 2: STRATEGIC LANDSCAPES PROFILES -

Appendix a Environmental Baseline

Appendix A Environmental Baseline . Introduction The data collected to characterise the baseline environment of Telford and Wrekin Borough has been derived from numerous secondary sources, which are referenced as footnotes in this report. No new investigations or surveys have been undertaken. In some instances, it has been noted that different secondary sources present conflicting information and it has not been possible to verify which sources are the most accurate. Where this has been identified, the limitations have been noted. It should be noted that there is an abundance of environmental information available. However, the information presented in this Appendix has been chosen on the basis that it may be influenced or affected by the Local Flood Risk Management Strategy (LFRMS). Steps have been taken to avoid including information which is of no clear relevance to the LFRMS. It may be necessary to collect further data against which to assess the potential environmental effects of the LFRMS with regard to monitoring requirements. Population .. Population The topic of population is considered first in the baseline information, since the over-arching purpose of the LFRMS is to reduce flood risk to people and property. The LFRMS also seeks to increase public awareness of flooding and promote individual and community level flood resilience. A number of properties in the Telford and Wrekin Area are in areas at risk of flooding and were affected by flooding during the Summer 2007 floods. Some of the properties were affected by flooding from fluvial sources (streams, rivers) but many properties were affected from surface water flooding from sewers and drainsi.