University of Oklahoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intimations Surnames

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames H-K This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames H-K Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage HAASE / LEGRING 1858 Frederick Auguste Haase, chief steward SS Bremen, to Ottile Wilhelmina Louise Amelia Legring, daughter of Reverend Charles Legring, Bremen, at Greenock on 24th May 1858 by Reverend J. Nelson. (Greenock Advertiser 25.5.1858) Marriage HAASE / OHLMS 1894 William Ohlms, hairdresser, 7 West Blackhall Street, to Emma, 4th daughter of August Haase, Herrnhut, Saxony, at Glengarden, Greenock on 6th June 1894 .(Greenock Telegraph 7.6.1894) Death HACKETT 1904 Arthur Arthur Hackett, shipyard worker, husband of Mary Jane, died at Greenock Infirmary in June 1904. (Greenock Telegraph 13.6.1904) Death HACKING 1878 Samuel Samuel Craig, son of John Hacking, died at 9 Mill Street, Greenock on 9th January 1878. -

City of Glasgow and Clyde Valley 3 Day Itinerary

The City of Glasgow and The Clyde Valley Itinerary - 3 Days 01. Kelvin Hall The Burrell Collection A unique partnership between Glasgow Life, the University of The famous Burrell Collection, one of the greatest art collections Glasgow and the National Library of Scotland has resulted in this ever amassed by one person and consisting of more than 8,000 historic building being transformed into an exciting new centre of objects, will reopen in Spring 2021. Housed in a new home in cultural excellence. Your clients can visit Kelvin Hall for free and see Glasgow’s Pollok Country Park, the Burrell’s renaissance will see the National Library of Scotland’s Moving Image Archive or take a the creation of an energy efficient, modern museum that will tour of the Glasgow Museums’ and the Hunterian’s store, alongside enable your clients to enjoy and better connect with the collection. enjoy a state-of-the art Glasgow Club health and fitness centre. The displays range from work by major artists including Rodin, Degas and Cézanne. 1445 Argyle Street Glasgow, G3 8AW Pollok Country Park www.kelvinhall.org.uk 2060 Pollokshaws Road Link to Trade Website Glasgow. G43 1AT www.glasgowlife.org.uk Link to Trade Website Distance between Kelvin Hall and Clydeside Distillery is 1.5 miles/2.4km Distance between The Burrell Collection and Glasgow city centre The Clydeside Distillery is 5 miles/8km The Clydeside Distillery is a Single Malt Scotch Whisky distillery, visitor experience, café, and specialist whisky shop in the heart of Glasgow. At Glasgow’s first dedicated Single Malt Scotch Whisky Distillery for over 100 years, your clients can choose a variety of tours, including whisky and chocolate paring. -

Scotland's Historic Cities D N a L T O C

Scotland's Historic Cities D N A L T O C Tinto Hotel S Holiday Inn Edinburgh Edinburgh Castle ©Paul Tompkins,Scottish ViewPoint 5 DAYS from only £142 Tinto Hotel Holiday Inn Edinburgh NEW What To Do Biggar Edinburgh Edinburgh Scotland’s capital offers endless possibilities including DOUBLE FOR TRADITIONAL DOUBLE FOR Edinburgh Castle, Royal Yacht Britannia, The Queen’s EXCELLENT SINGLE SCOTTISH SINGLE official Scottish residence – The Palace of Holyroodhouse PUBLIC AREAS and the Scotch Whisky Heritage Centre. The Royal Mile, OCCUPANCY HOTEL OCCUPANCY the walk of kings and queens, between Edinburgh Castle and Holyrood Palace is a must to enjoy Edinburgh at its historical best. If the modern is more for you, then the This charming 3 star property was originally built as a This 4 star Holiday Inn is located on the main road to shops and Georgian buildings of Princes Street are railway hotel and has undergone refurbishment to return it Edinburgh city centre being only 2 miles from Princes Street. perfect for those browsing for a bargain! to its former glory. With wonderfully atmospheric public This hotel has a spacious modern open plan reception, areas and a large entertainment area, this small hotel is restaurant, lounge and bar. All 303 air conditioned Glasgow deceptively large. Each of the 40 bedrooms is traditionally bedrooms are equipped with tea/coffee making facilities and Scotland’s second city has much to offer the visitor. furnished with facilities including TV, hairdryer, and TV. Leisure facilities within the hotel include swimming pool, Since its regeneration, Glasgow is now one of the most tea/coffee making facilities. -

National Programme 2017/2018 2

National Programme 2017/2018 2 National Programme 2017/2018 3 National Programme 2017/2018 National Programme 2017/2018 1 National Programme Across Scotland Through our National Strategy 2016–2020, Across Scotland, Working to Engage and Inspire, we are endeavouring to bring our collections, expertise and programmes to people, museums and communities throughout Scotland. In 2017/18 we worked in all of Scotland’s 32 local authority areas to deliver a wide-ranging programme which included touring exhibitions and loans, community engagement projects, learning and digital programmes as well as support for collections development through the National Fund for Acquisitions, expert advice from our specialist staff and skills development through our National Training Programme. As part of our drive to engage young people in STEM learning (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths), we developed Powering Up, a national science engagement programme for schools. Funded by the ScottishPower Foundation, we delivered workshops on wind, solar and wave energy in partnership with the National Mining Museum, the Scottish Maritime Museum and New Lanark World Heritage Site. In January 2017, as part of the final phase of redevelopment of the National Museum of Scotland, we launched an ambitious national programme to support engagement with Ancient Egyptian and East Asian collections held in museums across Scotland. Funded by the National Lottery and the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, the project is providing national partnership exhibitions and supporting collection reviews, skills development and new approaches to audience engagement. All of this work is contributing to our ambition to share our collections and expertise as widely as possible, ensuring that we are a truly national museum for Scotland. -

BEST of BRITISH 16 FASCINATING DAYS | LONDON RETURN We Take the Time to Do Britain Justice…

BEST OF BRITISH 16 FASCINATING DAYS | LONDON RETURN We take the time to do Britain justice…. from Stonehenge to the ‘bravehearts’ of Scotland and Tintern’s romantic Abbey. Discover the Kingmakers of Warwick and learn of Australia’s own heritage in Captain Cook’s Whitby. Soak up the history of Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon and indulge in traditional British fare. As a finale, be treated like royalty with an overnight stay in magnificent Leeds Castle! TOUR INCLUSIONS ALL excursions, scenic drives, sightseeing and entrances as described Fully escorted by our experienced Tour Manager Travel in a first class air-conditioned touring coach 15 nights specially selected hotel accommodation Hotel porterage (1 bag per person) 25 Meals – including breakfast daily, 1 lunch and 9 dinners Tea, coffee and a complimentary beverage with all included dinners Afternoon tea at Betty’s tearooms in Harrogate Hand Selected Albatross Experiences - Private cruise Lake Windermere, Captain Cook's Whitby Local guides as described in the itinerary ALL tips to your Tour Manager, Driver and Local Guides Personal audio system whilst on tour Free WiFi at hotels Add a subheading “The places we visited were wonderful. We enjoyed the unique THE ALBATROSS DIFFERENCE hotel accommodation and the most Leisurely 2 and 3 night stays special place was of course Leeds Small group sizes - from just 10 to 28 Castle where we were made to feel Genuinely inclusive, NO extra 'on tour' costs very important.” Ellaine & Kim Stay in traditional style hotels in superb locations Easier days with 'My Time' guaranteed! TOUR ITINERARY: BEST OF BRITISH Day 1: Stonehenge and Bath Your tour departs from central London at 9am. -

New Lanark World Heritage Site

New Lanark World Heritage Site A Short Guide April 2019 NIO M O U N IM D R T IA A L • • P • • W L L O A I R D L D N H O E M R E I T N A I G O E • PATRI M United Nations New Lanark Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World Cultural Organization Heritage List in 2001 Contents Introduction 1 New Lanark WHS: Key Facts 2 The World Heritage Site and Bufer Zone 3 Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 5 Managing New Lanark 6 Planning and New Lanark WHS 8 Further Information and Contacts 10 Cover image: Aerial view of New Lanark. Introduction This short guide is an introduction to New Lanark World Heritage Site (WHS), its inscription on the World Heritage List, and its management and governance. It is one of a series of Site-specifc short guides for each of Scotland’s six WHS. For information outlining what World Heritage status is and what it means, the responsibilities and benefts attendant upon achieving World Heritage status, and current approaches to protection and management see the SHETLAND World Heritage in Scotland short guide. See Further Information and Contacts or more information. ORKNEY 1 Kirkwall Western Isles Stornoway St kilda 2 Inverness Aberdeen World Heritage Sites in Scotland KEY: Perth 1 Heart of Neolithic Orkney 2 St Kilda Forth Bridge 6 5 3 3 Frontiers of the Roman Empire: Edinburgh Antonine Wall Glasgow 4 4 NEW LANARK 5 Old and New Towns of Edinburgh 6 Forth Bridge 1 New Lanark WHS: Key Facts • Inscribed on the World Heritage List in • New Lanark village remains a thriving 2001 as a cultural WHS. -

Regents Exam in Global History and Geography Ii (Grade 10)

REGENTS EXAM IN GLOBAL HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY II (GRADE 10) The University of the State of New York REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION REGENTS EXAM IN GLOBAL HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY II (GRADE 10) Tuesday, August 13, 2019 — 12:30 to 3:30 p.m., only Student Name _____________________________________________________________ School Name ______________________________________________________________ The possession or use of any communications device is strictly prohibited when taking this examination. If you have or use any communications device, no matter how briefl y, your examination will be invalidated and no score will be calculated for you. Print your name and the name of your school on the lines above. A separate answer sheet has been provided to you. Follow the instructions from the proctor for completing the student information on your answer sheet. Then fi ll in the heading of each page of your essay booklet. This examination has three parts. You are to answer all questions in all parts. Use black or dark-blue ink to write your answers to Parts II and III. Part I contains 28 multiple-choice questions. Record your answers to these questions as directed on the answer sheet. Part II contains two sets of constructed-response questions (CRQ). Each constructed- response question set is made up of two documents accompanied by several questions. When you reach this part of the test, enter your name and the name of your school on the fi rst page of this section. Write your answers to these questions in the examination booklet on the lines following these questions. Part III contains one essay question based on fi ve documents. -

Youth Travel SAMPLE ITINERARY

Youth Travel SAMPLE ITINERARY For all your travel trade needs: www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com Day One Riverside Museum Riverside Museum is Glasgow's award-winning transport museum. With over 3,000 objects on display there's everything from skateboards to locomotives, paintings to prams and cars to a Stormtrooper. Your clients can get hands on with our interactive displays, walk through Glasgow streets and visit the shops, bar and subway. Riverside Museum Pointhouse Place, Glasgow, G3 8RS W: http://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums Glasgow Powerboats A unique city-centre experience. Glasgow Powerboats offer fantastic fast boat trip experiences on the River Clyde from Pacific Quay in the heart of Glasgow right outside the BBC Scotland HQ. From a 15-minute City Centre transfer to a full day down the water they can tailor trips to your itinerary. Glasgow Powerboats 50 Pacific Quay, Glasgow, G51 1EA W: https://powerboatsglasgow.com/ Glasgow Science Centre Glasgow Science Centre is one of Scotland's must-see visitor attractions. It has lots of activities to keep visitors of all ages entertained for hours. There are two acres of interactive exhibits, workshops, shows, activities, a planetarium and an IMAX cinema. Your clients can cast off in The Big Explorer and splash about in the Waterways exhibit, put on a puppet show and master the bubble wall. Located on the Pacific Quay in Glasgow City Centre just a 10-minute train journey from Glasgow Central Station. Glasgow Science Centre 50 Pacific Quay, Glasgow, G51 1EA For all your travel trade needs: www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com W: https://www.glasgowsciencecentre.org/ Scottish Maritime Museum Based in the West of Scotland, with sites in Irvine and Dumbarton, the Scottish Maritime Museum holds an important nationally recognised collection, encompassing a variety of historic vessels, artefacts, fascinating personal items and the largest collection of shipbuilding tools and machinery in the country. -

Periodical Guide for Computerists 1977

PERIODICAL GUIDE FOR COMPUTERISTS An Index of Magazine Articles for Computer Hobbyists January - December 1977 PERIODICAL GUIDE FOR COMPUTERISTS 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS AMATEUR RADIO---------------------- 3 MICROCOMPUTERS ANALOG HARDWARE AND CIRCUITS------- 3 GENERAL------------------------- 36 APPLICATIONS, GENERAL-------------- 4 FUNDAMENTALS AND DESIGN--------- 37 ART--------------------------------5 SELECTION GUIDE----------------- 38 ASTRONOMY--------------------------6 AL TAI R 8800 & 680--------------- 38 BAR CODES--------------------------6 APPLE---------------------------39 BIORYTHMS--------------------------6 DI GIT AL GROUP------------------- 39 BIO FEEDBACK------------------------ 6 ELF & VIP ( COSMAC)-------------- 39 BOOKS AND PUBLICATIONS-------------6 HEATHKIT------------------------ 39 BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTING------------ 7 IMSAI--------------------------- 39 CALCULATORS------------------------ 8 INTERCEPT IM6100---------------- 39 CLUBS AND ORGANIZATIONS------------ 9 KIM----------------------------- 39 CLOCKS-----------------------------·9 PET----------------------------- 40 COMMUNICATION---------------------- 10 RADIO SHACK--------------------- 40 CONSTRUCTION----------------------- 10 SOL----------------------------- 40 CONTROL---------------------------- 11 SPHERE-------------------------- 40 CON VE RS ION, CODE------------------- 11 SWTPC--------------------------- 40 CONVERSION, NUMBER BASE------------ 11 WAVE MATE----------------------- 40 DEBUG------------------------------ 12 OTHER MICROCOMPUTERS------------ 41 -

Timeline & Bibliography

“The Happiest Days of My Life” Searching for Utopia in Tennessee Timeline and Bibliography Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North, Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 Timeline : Major Utopian Colonies 1800 Second Great Revival: religious outpouring across the mid-South follows five-day revivals during which people spoke in tongues, fell to the ground, entered near-comas, and professed their faith. 1800-50 Significant religious and political utopian communities are planted in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee. 1808 Congress bans the importation of slaves into the U.S. after January 1, 1808, but slave shipments to American will continue virtually unchallenged until 1859. 1809 Shaker colonies are established at South Union and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky. 1814 The Harmony Society, religious separatists led by George Rapp, found Harmonie on the Wabash in New Harmony, Indiana. 1816 The American Colonization society is formed to encourage and enable the resettlement of American slaves in Africa. Their efforts will lead to the founding of Liberia in 1820. 1819 The Panic of 1819 is the country’s first major financial crisis, with widespread unemploy- ment, numerous bank foreclosures, and a decline in manufacturing and agriculture. 1825-26 Fanny Wright buys 4,000 acres of land in West Tennessee for her utopian experiment at Nashoba. The venture is political and cultural rather than religious: Nashoba’s interracial community is an early effort to provide an alternative to slavery. 1825 The Harmonists move to Economy, Pennsylvania. Robert Owen, hoping to create a more perfect society through free education and the abolition of social classes and personal wealth, buys their remarkably well-planned Indiana town and the surrounding lands for his communitarian experiment, New Harmony. -

The Origins and Development of the Fabian Society, 1884-1900

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1986 The Origins and Development of the Fabian Society, 1884-1900 Stephen J. O'Neil Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation O'Neil, Stephen J., "The Origins and Development of the Fabian Society, 1884-1900" (1986). Dissertations. 2491. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2491 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1986 Stephen J. O'Neil /11/ THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE FABIAN SOCIETY, 1884-1900 by Stephen J. O'Neil A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 1986 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is the product of research over several years' span. Therefore, while I am endebted to many parties my first debt of thanks must be to my advisor Dr. Jo Hays of the Department of History, Loyola University of Chicago; for without his continuing advice and assistance over these years, this project would never have been completed. I am also grateful to Professors Walker and Gutek of Loyola who, as members of my dissertation committee, have also provided many sug gestions and continual encouraqement in completing this project. -

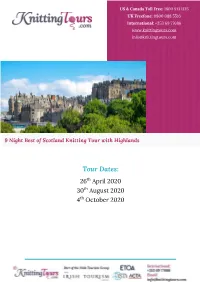

Tour Dates: 26Th April 2020 30Th August 2020 4Th October 2020

Get in Touch: US & Canada Toll Free: 1800 913 1135 UK Freefone: 0800 088 5516 International: +353 69 77686 www.knittingtours.com [email protected] 9 Night Best of Scotland Knitting Tour with Highlands Tour Dates: 26th April 2020 30th August 2020 4th October 2020 Tour Overview This Scottish knitting tour will help you experience craft in Scotland with an emphasis on knitting. Your tour will include a tour of Edinburgh and Edinburgh Castle. Visit New Lanark Mill, a famous world heritage site, the village of Sanquhar known for its unique Sanquhar knitting pattern. You will spend time in Glasgow, a port city on the River Clyde and the largest city in Scotland, from here we will travel along the shores of Loch Lomond to Auchindrain Township where you will be treated to a special recreation of ‘waulking with wool’. On this tour we will visit Johnsons Mill in Elgin, Scotland’s only remaining vertical mill! In Fife we will visit Claddach farm and learn more about the Scottish sheep, goats and Alpacas that are reared to produce the finest Scottish wool. There will be three half day workshops on this tour: we will meet with Emily from Tin Can Knits in Edinburgh, in Elgin we will enjoy a workshop on our April tour with ERIBE and our August and October tours with Sarah Berry of North Child and in Fife you will take part in a workshop with Di Gilpin and her team. Of course no tour of Scotland is complete without visiting a whisky distillery! Your tour includes a tour of a Speyside Distillery with a whisky tasting in Scotland’s famous whisky producing area.