ROCK GARDEN COVER: Eriogonum Umbellatum Ssp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Possible Roles of Eucomis Autumnalis in Bone and Cartilage Regeneration: a Review

Alaribe et al Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research April 2018; 17 (4): 741-749 ISSN: 1596-5996 (print); 1596-9827 (electronic) © Pharmacotherapy Group, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin City, 300001 Nigeria. Available online at http://www.tjpr.org http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v17i4.25 Review Article Possible roles of Eucomis autumnalis in bone and cartilage regeneration: A review Franca N Alaribe, Makwese J Maepa, Nolutho Mkhumbeni, Shirley CKM Motaung Department of Biomedical Sciences, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria 0001, South Africa *For correspondence: Email: [email protected]; Tel: +27-123826265/6333; Fax: +27-123826262 Sent for review: Revised accepted: 23 October 2017 Abstract In response to the recent alarming prevalence of cancer, osteoarthritis and other inflammatory disorders, the study of anti-inflammatory and anticancer crude medicinal plant extracts has gained considerable attention. Eucomis autumnalis is a native flora of South Africa with medicinal value. It has been found to have anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, anti-tumor/cancer, anti-oxidative and anti- histaminic characteristics and produces bulb that have therapeutic value in South African traditional medicine. Despite the widely acclaimed therapeutic values of Eucomis autumnalis, its proper identification and proper knowledge, morphogenetic factors are yet to be efficiently evaluated. Similar to other plants with the same characteristics, E. autumnalis extract may stimulate bone formation and cartilage regeneration by virtue of its anti-inflammatory properties. This review provides data presented in the literature and tries to evaluate the three subspecies of E. autumnalis, highlighting their geographical location in South African provinces, their toxicity effects, as well as their phytochemistry and anti-inflammatory properties. -

1 Retail Listings 2011 by USDA Zone, As of Sept 5 - Please Check for Current Availability

1 Retail listings 2011 by USDA zone, as of Sept 5 - please check for current availability USDA zone: 2 Alcea rosea 'Nigra' Classic hollyhock with dark maroon, nearly black flowers covering the 5-8 ft spires in July and August. They like well-drained soil and full to part sun with average summer water. Short-lived, they reseed easily establishing long-lived colonies. Frost hardy in USDA zone 2. 4in @ $3 Malvaceae Lindelofia longiflora Bright blue flowered cousin of a forget-me-not which blooms from late spring to frost. Long-live perennial, clumping to 2 ft by 2 ft in rich, moist soil in a half shady spot– think woodland. Great for a border that gets some water, but not much attention otherwise. Hardy to 25 below. 6in @ $12 Boraginaceae Physocarpus opulifolius 'Dart's Gold' golden ninebark Its golden foliage highlights the pure white, fragrant, summer flowers and brilliant red fruit in autumn. Peeling bark adds interest to this durable hedging plant or specimen, deciduous, to 5 ft tall and wide, smaller than the species. Out of the hottest afternoon sun seems to suit it best for foliage color. Can take a bit of drought, but best with a little summer water. Takes will to pruning. Frost hardy in USDA zone 2. 1g @ $12, 2g @ $22 Rosaceae Rosa glauca red leaf rose Grown as much for its foliage as its flowers this deciduous shrub, to 6 ft tall x 5 ft wide, has glaucous blue foliage and, in June, single pink flowers with white centers. Lovely rose hips follow and remain through the winter. -

Annual Report 12 N E W H a M P S H I R E M a S T E R G a R D E N E R S

20MASTER GARDENER Annual Report 12 N E W H A M P S H I R E M A S T E R G A R D E N E R S MISSION OUR GOALS Fast FACts there are... • provide distance learning opportunities with an emphasis on recruiting Master Gardener's in our North • 207 master gardeners volunteered The mission of UNH Cooperative Country Communities Extension is to provide 7749 hours at the county level New Hampshire citizens with • create on-line workshops that are accessible to our research-based education and Education Center volunteers on the days they volunteer information, to enhance their ability • 103 master gardeners from 5 counties • continue to update master gardener training to make informed decisions that volunteered over 3100 hours staffing strengthen youth, families and to focus on adult learners the information line at the ed center communities, sustain natural resources, • INCORPORATE ON-LINE LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES and improve the economy. that reflect needs identified in the Education Center As representatives of UNHCE, Business Plan master gardener volunteers • CREATE A STRONG MENTORING PROGRAM to assist and ACTIVE MASTER GARDENERS IN NEW HAMPSHIRE contribute to Extension’s ability to provide consumers with up-to-date, support our newest volunteers. reliable information by leading • DEVELOP VIRTUAL VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES to keep Belknap and participating in community volunteers engaged from a distance Carroll educational projects and answering Cheshire questions from the public • oFFER VOLUNTEER LEADERSHIP TRAINING for those Coos at the Education Center. volunteers seeking to take on leadership roles Grafton Hillsborough Merrimack Rockingham Strafford Sullivan ACTIVEMaster MASTER Gardeners GARDENERS REPORTING Dear Master Gardeners, 120 I am particularly proud of the work our Master Gardeners accomplished with the youngest, the 100 oldest, and the most vulnerable of our fellow New 80 Hampshirites. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

Title Studies in the Morphology and Systematics of Berberidaceae (V

Studies in the Morphology and Systematics of Berberidaceae Title (V) : Floral Anatomy of Caulophyllum MICHX., Leontice L., Gymnospermium SPACH and Bongardia MEY Author(s) Terabayashi, Susumu Memoirs of the Faculty of Science, Kyoto University. Series of Citation biology. New series (1983), 8(2): 197-217 Issue Date 1983-02-28 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/258852 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University MEMolRs OF THE FAcuLTy ol" SclENCE, KyOTO UNIvERslTy, SERMS OF BIoLoGy Vol. VIII, pp. 197-217, March l983 Studies in the Morphology and Systematics of Berberidaceae V. Floral Anatomy ef Cauloplrytlum MICHX., Leontice L., Gymnospermium SpACH and Bongardia MEY. Susumu TERABAYASHI (Received iNovember 13, l981) Abstract The floral anatomy of CauloPh71tum, Leontice, G"mnospermittm and Bongardia are discussed with special reference given to vasculature. Comparisons offloral anatomy are made with the other genera og the tribe Epimedieae. The vasculature in the receptacle of Caulopnjilum, Leontice and G]mnospermiitm is similar, but that of Bongardia differs in the very thick xylem of the receptacular stele and in the independent origin ef the traces to the sepals, petals and stamens from the stele. A tendency is recognized in that the outer floral elements receive traces ofa sing]e nature in origin from the stele while the inner elements receive traces ofa double nature. The traces to the inner e}ements are often clerived from common bundles in Caulop/tyllttm, Leontice and G"mnospermittm. A similar tendency is observed in the trace pattern in the other genera of Epimedieae, but the adnation of the traces is not as distinct as in the genera treated in this study. -

Mccaskill Alpine Garden, Lincoln College : a Collection of High

McCaskill Alpine Garden Lincoln College A Collection of High Country Native Plants I/ .. ''11: :. I"" j'i, I Joy M. Talbot Pat V. Prendergast Special Publication No.27 Tussock Grasslands & Mountain Lands Institute. McCaskill Alpine Garden Lincoln College A Collection of High Country Native Plants Text: Joy M. Tai bot Illustration & Design: Pat V. Prendergast ISSN 0110-1781 ISBN O- 908584-21-0 Contents _paQ~ Introduction 2 Native Plants 4 Key to the Tussock Grasses 26 Tussock Grasses 27 Family and Genera Names 32 Glossary 34 Map 36 Index 37 References The following sources were consulted in the compilation of this manual. They are recommended for wider reading. Allan, H. H., 1961: Flora of New Zealand, Volume I. Government Printer, Wellington. Mark, A. F. & Adams, N. M., 1973: New Zealand Alpine Plants. A. H. & A. W. Reed, Wellington. Moore, L.B. & Edgar, E., 1970: Flora of New Zealand, Volume II. Government Printer, Wellington. Poole, A. L. & Adams, N. M., 1980: Trees and Shrubs of New Zealand. Government Printer, Wellington. Wilson, H., 1978: Wild Plants of Mount Cook National Park. Field Guide Publication. Acknowledgement Thanks are due to Dr P. A. Williams, Botany Division, DSIR, Lincoln for checking the text and offering co.nstructive criticism. June 1984 Introduction The garden, named after the founding Director of the Tussock Grasslands and Mountain Lands Institute::', is intended to be educational. From the early 1970s, a small garden plot provided a touch of character to the original Institute building, but it was in 1979 that planning began to really make headway. Land scape students at the College carried out design projects, ideas were selected and developed by Landscape architecture staff in the Department of Horticul ture, Landscape and Parks, and the College approved the proposals. -

Fair Use of This PDF File of Herbaceous

Fair Use of this PDF file of Herbaceous Perennials Production: A Guide from Propagation to Marketing, NRAES-93 By Leonard P. Perry Published by NRAES, July 1998 This PDF file is for viewing only. If a paper copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Be aware that practices, recommendations, and economic data may have changed since this book was published. Text can be copied. The book, authors, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgement: ----From Herbaceous Perennials Production: A Guide from Propagation to Marketing, NRAES- 93, by Leonard P. Perry, and published by NRAES (1998).---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. This PDF should not be used to make copies of the book for sale or distribution. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES’ secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. Quantity discounts are available. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org More information on NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. Acknowledgments This publication is an update and expansion of the 1987 Cornell Guidelines on Perennial Production. Informa- tion in chapter 3 was adapted from a presentation given in March 1996 by John Bartok, professor emeritus of agricultural engineering at the University of Connecticut, at the Connecticut Perennials Shortcourse, and from articles in the Connecticut Greenhouse Newsletter, a publication put out by the Department of Plant Science at the University of Connecticut. -

Pre and Post-Fire Monitoring of Kalmiopsis Fragrans on the Umpqua National Forest 2012 Progress Report

Pre and post-fire monitoring of Kalmiopsis fragrans on the Umpqua National Forest 2012 progress report Prepared by Kelly Amsberry, Amy Golub-Tse, and Robert Meinke for U.S. Forest Service, Umpqua National Forest (No. 04-CS-11061500-027) March 18, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Species description ............................................................................................................................. 2 Habitat ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Threats ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Project 1: Wildfire study ......................................................................................................................... 4 Project 2: Prescribed fire study ............................................................................................................. 5 2014 Tasks .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Acknowledgement ................................................................................................................................. -

Desiderata June 2021

Desiderata June 2021 Desiderata are plants that National Collection Holders are searching for to add to their collections. Many of these plants have been in cultivation in the UK at some point, but they are not currently obtainable through the trade. Others may appear available in the trade, but doubts exist as to whether the material currently sold is correctly named. If you know where some of these plants may be growing, whether it is in the UK or abroad,please contact us at [email protected] 01483 447540, or write to us at : Plant Heritage, 12 Home Farm, Loseley Park, Guildford GU3 1HS, UK. Abutilon ‘Apricot Belle’ Artemisia villarsii Abutilon ‘Benarys Giant’ Arum italicum subsp. italicum ‘Cyclops’ Abutilon ‘Golden Ashford Red’ Arum italicum subsp. italicum ‘Sparkler’ Abutilon ‘Heather Bennington’ Arum maculatum ‘Variegatum’ Abutilon ‘Henry Makepeace’ Aster amellus ‘Kobold’ Abutilon ‘Kreutzberger’ Aster diplostephoides Abutilon ‘Orange Glow (v) AGM’ Astilbe ‘Amber Moon’ Abutilon ‘pictum Variegatum (v)’ Astilbe ‘Beauty of Codsall’ Abutilon ‘Pink Blush’ Astilbe ‘Colettes Charm’ Abutilon ‘Savitzii (v) AGM’ Astilbe ‘Darwins Surprise’ Abutilon ‘Wakehurst’ Astilbe ‘Rise and Shine’ Acanthus montanus ‘Frielings Sensation’ Astilbe subsp. x arendsii ‘Obergartner Jurgens’ Achillea millefolium ‘Chamois’ Astilbe subsp. chinensis hybrid ‘Thunder and Lightning’ Achillea millefolium ‘Cherry King’ Astrantia major subsp. subsp. involucrata ‘Shaggy’ Achillea millefolium ‘Old Brocade’ Azara celastrina Achillea millefolium ‘Peggy Sue’ Azara integrifolia ‘Uarie’ Achillea millefolium ‘Ruby Port’ Azara salicifolia Anemone ‘Couronne Virginale’ Azara serrata ‘Andes Gold’ Anemone hupehensis ‘Superba’ Azara serrata ‘Aztec Gold’ Anemone x hybrida ‘Elegantissima’ Begonia acutiloba Anemone ‘Pink Pearl’ Begonia almedana Anemone vitifolia Begonia barkeri Anthemis cretica Begonia bettinae Anthemis cretica subsp. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

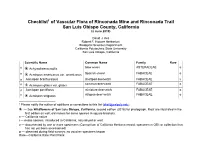

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

Mountain Plants of Northeastern Utah

MOUNTAIN PLANTS OF NORTHEASTERN UTAH Original booklet and drawings by Berniece A. Andersen and Arthur H. Holmgren Revised May 1996 HG 506 FOREWORD In the original printing, the purpose of this manual was to serve as a guide for students, amateur botanists and anyone interested in the wildflowers of a rather limited geographic area. The intent was to depict and describe over 400 common, conspicuous or beautiful species. In this revision we have tried to maintain the intent and integrity of the original. Scientific names have been updated in accordance with changes in taxonomic thought since the time of the first printing. Some changes have been incorporated in order to make the manual more user-friendly for the beginner. The species are now organized primarily by floral color. We hope that these changes serve to enhance the enjoyment and usefulness of this long-popular manual. We would also like to thank Larry A. Rupp, Extension Horticulture Specialist, for critical review of the draft and for the cover photo. Linda Allen, Assistant Curator, Intermountain Herbarium Donna H. Falkenborg, Extension Editor Utah State University Extension is an affirmative action/equal employment opportunity employer and educational organization. We offer our programs to persons regardless of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age or disability. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Robert L. Gilliland, Vice-President and Director, Cooperative Extension