A DISCUSSION TOOL KIT: for Individuals, Community Groups and Organizations by Celebrating Diversity, We Find a Universal Humanity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Lights

NORTHERN LIGHTS News, notes and updates from December 2018 Northern Hills United Methodist Church. 6700 Winton Road Cincinnati, Ohio 45224 (513) 542-4010 [email protected] Friend us on Facebook Office Hours Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday 1 pm to 4 pm Join Us For Worship On Sunday Morning 9:00 AM Adult Sunday School 10:00 AM Nursery 10:00 AM Worship 10:20 AM Children's Sunday School 11:00 AM Fellowship Hour Upcoming Events NHUMC STAFF december Kevin Gruver, Pastor Joanna Kenyon, Worship Music Leader Donna Medlock, Choir Director Emeritus Dr. Ian Scott, Pianist Sara Croxton, Nursery Director Patrice Callery, Children’s Choir 8 Breakfast with Santa 9 Family Christmas Program 13 Kid’s Clothing Closet 16 Deliver Gifts to WHA Families 17 Newsletter Deadline 18 Lunch Bunch January Newsletter 24 Christmas Eve Deadline - Monday 25 Christmas Day December 17 @ 1 PM 31 New Year’s Eve Dear Church Family, As Christmas is approaching, let me remind you of the reason for the season. We will be celebrat- ing the birth of our Savior, Jesus Christ, once again. It is so very easy to lose track of the birthday story in a cul- ture that makes it more about us and what we get for Christmas, than about him and his gift for us. As Christ fol- lowers we live between two dramatic events that changes history, called the already and the not yet. Jesus Christ has already come and given himself as a sacrifice for our sin; but he has not yet returned to claim that which is his, and to set the wrongs right in this world once again. -

Welcome to Cincinnati -- Queen City Destination

Welcome to Queen City I N T R O D U C I N G S O M E O F O U R F A V O R I T E C I N C Y S P O T S w w w . q u e e n c i t y d e s t i n a t i o n . c o m neighborhood spotlight: Over-the-Rhine Over-the-Rhine is a growing neighborhood rich in history and gorgeous 19th century architecture. Add in recent renovation and a bustling business scene, and it's become a favorite stop for locals and visitors alike. Findlay Market HISTORIC FINDLAY MARKET IS OHIO'S OLDEST, CONTINUOUSLY RUN PUBLIC MARKET. Home to 60+ full-time merchants, a vibrant Outdoor Market and our region's largest farmers market, Findlay Market is the premier fresh Findlay Market food destination and a gathering spot in our city. The market is open Tuesday-Sunday. Holtman's CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE. Donut Shop TAKE A MORNING JOG (OR RIDE A Washington LIME IN) TO OTR BEFORE YOUR CONFERENCE BEGINS AND GRAB Park SOME BREAKFAST FOR THE TEAM. WASHINGTON PARK HAS A RICH Established in 1960, Holtman's HERITAGE AS THE CENTER OF Donuts, located in Loveland, OVER-THE-RHINE'S Williamsburg and now OTR, is family MULTIGENERATIONAL, owned since 1960. Holtman's MULTIETHNIC DISTRICT. continues their tradition by making To this day, it serves as the epicenter donuts from scratch using the highest of OTR. Picnic at the park with your quality ingredients. -

CR16-Shaheen.Pdf

Hollywood’s Bad Arabs By Jack G. Shaheen s it easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for an Arab to appear as a genuine human being?” I posed this question forty years ago, when I first Ibegan researching Arab images. My children, Michael and Michele, who were six and five years old at the time, are, in part, responsible. Their cries, “Daddy, Daddy, they’ve got bad Arabs on TV,” motivated me to devote my professional career to edu- cating people about the stereotype. It wasn’t easy. Back then my literary agent spent years trying to find a publisher; he told me he had never before encountered so much prejudice. He received dozens of rejection letters before my 1984 book, The TV Arab, the first ever to document TV’s Arab images, made its debut, thanks to Ray and Pat Browne, who headed up Bowling Green State University Popular Press. The Brownes came to our rescue. Regrettably, the damaging stereotypes that infiltrated the world’s living rooms when The TV Arab was first released—billionaires, bombers, and belly dancers—are still with us today. In my subsequent book Reel Bad Arabs I documented both positive and negative images in Hollywood portrayals of Arabs dating back to The Sheik (1921) starring Rudolph Valentino. The Arab-as-villain in cinema remains a pervasive motif. This stereotype has a long and powerful history in the United States, but since the September 11 attacks it has extended its malignant wingspan, casting a shadow of distrust, prejudice, and fear over the lives of many American Arabs. -

Gold Star Bengals Ticket Package Sweepstakes OFFICIAL RULES

Gold Star Bengals Ticket Package Sweepstakes OFFICIAL RULES 1. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER OR TO WIN THIS SWEEPSTAKES. ALL FEDERAL, STATE, LOCAL AND MUNICIPAL LAWS AND REGULATIONS APPLY. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED. 2. Eligibility. Subject to the additional restrictions below, the Gold Star Bengals Ticket Package Sweepstakes (the “Sweepstakes”) is open to participants who are: (i) legal residents of the States of Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky; (ii) 18 years or older at the time of entry. Employees of Gold Star Chili, Inc. (“Sponsor”) and its affiliated companies, subsidiaries, and advertising and promotional agencies, and the family members of, and any persons domiciled with, any such employees, are not eligible to enter or to win. The term “family members” includes spouses, parents, grandparents, siblings, children, grandchildren and in-laws, regardless of where they live. Persons belonging to or affiliated with a professional acting, theater, or film-making organization, such as SAG or AFTRA, are not allowed to compete in the Sweepstakes or participate in any entry. Professional actors and filmmakers, whether full-time or part-time, are allowed to compete so long as they do not belong to any professional organizations connected with the entertainment industry that would cause Sponsor to pay the entrant or any other person a fee or any other benefit for taking part in any Sweepstakes event. 3. How to Enter. The Sweepstakes will begin at 12:01 a.m. Eastern Standard Time (“EST”) on October 1, 2020, and end at 11:59 p.m. EST on December 27, 2020 (“Entry Period”). Sponsor will be the official timekeeper for the Sweepstakes. -

Ohio and the World. INSTITUTION Ohio Council for the Studies, Oxford

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 198 044 SO 013 117 AUTHOR Fuller, Michael J. TITLE Ohio and the World. INSTITUTION Ohio Council for the Studies, Oxford. PUB DATE 30 NOTE 195p.: Some advertisements and tables may not reproduce clearly from EDRS in Paper copy or microfiche. Funding made available through the Mid-America Program for Global Perspectives in Education. AVAILABLE FPCMOhio Council for the Social Studies, Teacher Education Department, 307B McGuffey Hall, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056 ($4.81). EDRS PRICE mral/pcos Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities: Community Study; Cultural Awaren.Iss: Ethnic Origins: *Global Approach: /nteT-hational Relttiors: Local History: Secondary Education: *Social Studies: State History: Teaching Gniies: Units of Study: World Affeirs TDENTTwrIlFS *Ohio ABSTRACT The 23 lessons for use in secondary social studies courses will help increase student awareness andunderstanding of the growing ties between life in Ohio and in their hometowns andlife in villages and cities around the world. Although written specifically for use '_n Ohio schools, the lessons can easily be adapted for use in other states. Most of the lessons are self-contained and includeall the data and background information which students will need to complete the activities. The aGtivities are many and varied.. Some examples follow. In the opening lesson, students compile a list of countries to which they have direct connection either by personal experience or indirect connection through the consumption of goods and services. In another lesson students are given trademarks for various companies and then asked to identify those companies which are American owned and those which areforeign owned. In a lesson, U.S. -

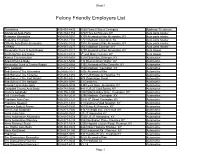

Felony Friendly Employers List

Sheet1 Felony Friendly Employers List Transitions 859-491-4435 1650 Russell Street Covington Addiction Treatment Advanced Auto Parts 859-384-1753 8707 Hwy 42 Florence KY Auto parts retailer Autozone Alexandria 859-635-1601 8109 Alexandria Pike Alexandria, KY Auto parts retailer Autozone Covington 859-261-7730 1721 Madison Covington, Ky Auto parts retailer O'Reilly Auto Parts Alexandria 859-592-9133 7918 Alexandria Pike Alexandria, KY Auto parts retailer O”Reilly 859-581-2277 1601 Madison Covinton, KY Auto parts retailer Alexandria Truck & Auto Repair 859-635-0127 9299 Alexandria Pike Alexandria, KY Auto Repair Smith Muffler and Brake 859-431-5728 5th and Main Covinton, KY Auto Repair Aamco Transmissions 859-344-8858 3210 Dixie Hwy, Erlanger, KY Automotive Airport Paint & Body 859-441-5000 114 Beacon Drive Wilder, KY Automotive Alexandria Truck & Tractor Repair 859-635-8568 5192 Alexandria Pike Claryville, KY Automotive BFC Autobody 859-431-2114 1500 Madison, Covington, KY Automotive Bob Sumerel Tire Alexandria 859-635-9777 7005 Alexandria Pike Automotive Bob Sumerel Tire Florence 859-283-1282 8711 US Route 42 Florence, KY Automotive Bob Sumerel Tire Fort Wright 859-341-6222 476 Orphanage Road Automotive Bob Sumerel Tire Newport 859-291-0091 63 Carothers Automotive Brossart Bros Auto Body 859-635-3035 8398 west Main, Alexandria, KY Automotive Campbell County Auto Body 859-781-5800 4411 US 27 Cold Spring, KY Automotive Crone's Autobody 859-356-1800 1008 Mary Laidley Drive, Covington, KY Automotive D & J Auto Body 859-341-2038 3296 Madison, -

Eastern Progress 1983-1984 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1983-1984 Eastern Progress 2-2-1984 Eastern Progress - 02 Feb 1984 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1983-84 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 02 Feb 1984" (1984). Eastern Progress 1983-1984. Paper 19. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1983-84/19 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1983-1984 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Laboratory Publication of the Daparamnt of Man Communications Vol. 62/ No. 19 14 pages Thursday, February 2. 1984 Eastern Kentucky Unhwtfcy. Richmond. Ky. 40475 Vacancy Title IX requires election university to add selects new women's team By Thomas Barr in mind for women for a long lime.' Editor said Mullins. As a result of recommendations "PersonaDy. I think swimming and senators made by the Office of Civil Rights softball are a far better bet as far as By Lisa Frost (OCR) last spring, the university will my recommendation goes." said News editor add another varsity women's Mullins. "There's been more interest The 15 vacant seats in the Student ntercollegiate sport by the next in those two sports and they give more Senate were filled Tuesday as 593 academic year. opportunity to more women. university students voted in the spring Under the guidelines of the Title IX One sport Mullins looked over was election, according to Sandy Steilberg. -

2017 Annual Report

2017 ANNUAL REPORT CINCINNATI MUSIC HALL CONTINUING ON ITS MISSION TO REVITALIZE CINCINNATI’S URBAN CORE, 3CDC 2017 also brought with it the exciting news that The Kroger Company had another positive year in 2017. With several large projects wrapping would be building its first downtown store since 1969, with 3CDC up, new projects beginning, tenants opening their doors for the first serving as the developer. Located at the corner of Court and Walnut time, and a vast array of new programming at some of Cincinnati’s most streets, the mixed-use development is estimated to cost $92 million intensely utilized civic spaces, this past year has been full of excitement. and will result in a multi-story, full-service Kroger grocery store, The renovation of two major civic spaces in Over-the-Rhine – Music Hall 560-space parking garage, and 139 market-rate apartments. and Ziegler Park – was a key focus of the organization in 2017. Though just recently completed, Ziegler Park has already started contributing to OUR PRIORITIES the renaissance in OTR, and Music Hall has returned to its former glory. Over the course of the summer, the $32 million renovation and expansion CREATE AND MANAGE GREAT CIVIC SPACES of Ziegler Park was completed, resulting in a brand new deep-water swimming pool, children’s playground, sprayground, civic lawn, and a PRESERVE HISTORIC STRUCTURES, IMPROVE STREETSCAPES, 400-space, two-level underground parking garage. Then, after more than AND BUILD HIGH-DENSITY, MIXED-USE PROJECTS a year of renovations to Music Hall, the historic gem reopened to the public in early October. -

FLY Tosporty's

Whether you arrive by car or by airplane, FLY TO Sporty’s the welcome mat is out for our customers Looking for a fun destination for a weekend flight? Put Sporty’s on your list. We’re on the east side of the runway at the Clermont County/Sporty’s Airport (I69) just outside Cincinnati, Ohio. Our facility includes our pilot shop, flight school, FBO, and full complement of services and amenities to make for a good trip. Famous Saturday cookouts Shop our newly-renovated store If you visit on a Saturday, you can enjoy our famous weekly cookout. Every Browse our newly-renovated retail store for hundreds of products that will Saturday between noon and 2pm, we grill hot dogs, metts, and brats in make your flying safer, easier, and more fun. Our headset wall allows you to appreciation of our customers. Meet a new friend around our charcoal grill compare the most popular models side-by-side—complete with simulated and share some flying stories. While you’re here, browse our lobby, which engine noise. Or talk to our knowledgeable staff about the latest iPad includes a Cessna 150 opened up, a jet engine, and our new timeline wall accessories, flight bags, and training materials. Open 10am - 6pm weekdays, that shows the 60-year history of Sporty’s. 10am - 5pm Saturday, and 11am - 3pm Sunday. Top-notch facilities Combine your visit Our airport has a 3700-foot runway with GPS and VOR approaches. Sporty’s Finish your visit to Sporty’s by including a tour of the on-airport Tri-State also hosts a full-service FBO with fuel, hangars, picnic pavilion, and avionics Warbird Museum. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Content Page How to use the Services Provided by UC International Services .................. Inside Front Cover Welcome to the University of Cincinnati ......................................................................... 1 I. Immigration Issues Important Immigration Documents ........................................................................... 2 Certi cate of Eligibility ........................................................................................ 2 I-94 Arrival/Departure Record ............................................................................ 2 Passport ............................................................................................................. 2 Visa .................................................................................................................... 2 Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) ................................. 3 SEVIS Fee ......................................................................................................... 3 Who Must Pay the Fee ....................................................................................... 3 Fee Payment Process ........................................................................................ 3 Visa Application and Initial Admission to the United States 5 Visa Application Process ................................................................................... 5 Security Checks ................................................................................................ -

Executive Plaza I & II 134 & 144 Merchant Street, Springdale, Ohio

Available Executive Plaza I & II 134 & 144 Merchant Street, Springdale, Ohio Property Highlights – 134 Merchant: 87,978 total s.f., three-story building – 144 Merchant: 89,579 total s.f., three-story building – Asking price is $60.00 / s.f. – Lease rate is $9.95 / s.f. NNN – Large, efficient footprints for full-floor or multi-tenancy occupancy – Signage opportunities available – Built in 1981, renovated in 2005 – Located on 10.85 total acres – Centrally located in Tri-County, between I-275 and I-75 with convenient highway access – Abundant parking for tenants, clients and guests; 4.3:1000 ratio - parking can be expanded for more dense call center users – Covered executive parking available beneath building – Within minutes to several nearby amenities including Tri-County Mall, shopping centers, restaurants, parks and entertainment Bill Poffenberger Rusty Myers Todd Pease +1 513 252 2107 +1 513 252 2158 +1 513 297 2506 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] jll.com/cincinnati Base Floorplans 134 Merchant Street 144 Merchant Street Amenities 2 9 10 3 26 10 Tri-County 1 Mall 8 2 4 6 7 13 14 1 27 11 12 25 3 24 4 5 15 16 4 2 3 17 2 18 22 23 21 1 1 19 3 4 20 5 5 6 6 Dining Hotels & Venues Entertainment 1 O’Charley’s 10 Outback Steakhouse 19 Tokyo Japanese 1 Residence Inn by Marriott 1 Tri County Golf Ranch Dos Amigos Mexican Starbucks 20 Manor House 2 Econo Lodge 2 Dave & Buster’s 2 Benihana Chipotle BJ’s Brewhouse 21 Domino’s Pizza 3 Extended Stay America 3 Sky Zone Trampoline Park 3 Jade Buffet Full Throttle -

Program Book and Abstracts

PROGRAM BOOK AND ABSTRACTS Marriott Kingsgate Conference Center Cincinnati, Ohio May 11-13, 2012 Sponsored by Table of Contents WELCOME MESSAGE ......................................................................................................... 2 CONFERENCE AT A GLANCE May 11-13, 2012 ............................................................................................................... 3 POSTER LISTING ................................................................................................................ 6 LOCAL RESTAURANT GUIDE .......................................................................................... 8 ORAL PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS .................................................................................. 9 POSTER ABSTRACTS ......................................................................................................... 20 ABSTRACT INDEX .............................................................................................................. 31 ATTENDEE ROSTER ........................................................................................................... 32 NOTES ............................................................................................................................... 36 1 Welcome Message Dear Participant, We would like to personally welcome each of you to the National Conference for Workplace Violence Prevention & Management in Healthcare Settings. Workplace violence has been a problem for healthcare workers and employers for many years. Unfortunately,