Canada: One Country, Two Cultures: Two Routes to Science Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual R Eport 2 009-2

The Science Media Centre of Canada | Annual Report 2009-2010 CONTENTS Introduction 1 SMCC Overview 2 The Year Ahead 3 Letter from the Founding Chair 4 Letter from the Executive Director 6 Key Achievements 8 Financials 12 Special Acknowledgements 16 THE SCIENCE MEDIA CENTRE OF CANADA 1867 St.Laurent Blvd PO Box 9724, Station T MAIN NUMBERS: Ottawa, ON (613) 249-8209 K1G 5A3 (438) 288-3909 (403) 456-2109 EMAIL: [email protected] (604) 248-4209 FAX: 613-990-3654 (902) 442-6909 www.sciencemedia.ca (647) 729-1909 Science has never been more pervasive in everyday life, yet seldom have so many people felt so unconnected to it. Fewer and fewer specialized medi- cal and science journalists exist in the mass media. The burden has fallen instead on general assignment report- ers, who mostly lack the expertise to present science in an engaging fashion. In 2008, a small group of con- cerned journalists, researchers and public supporters of science decided the way to tackle this problem was primarily by providing help to general assignment reporters in the form of THE SCIENCE MEDIA CENTRE OF Canada. Inform public debate with evidence-based accurate science. Improve the quality and quantity of reporting in all fields of science. Increase public engagement with science issues through media coverage of science that is accurate, incisive, and evidence-based. Public debate and policy decisions will benefit. SMCC OVERVIEW The Science Media Centre of Canada (SMCC) The SMCC will give priority to helping will help journalists cover stories in which journalists who don’t have the luxury of science plays an important part. -

Annual Report 2010–2011

The Science Media Centre of Canada | Annual Report 2010–2011 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Message from the Chair 2 Message from the Executive Director 4 The SMCC by the numbers 6 Highlights 6 Key achievements 8 Objectives 9 Benefits 9 Champions 10 Editorial Advisory Committee 11 Board of Directors 11 Research Advisory Panel 12 Charter Members 13 Supporters 14 Staff 14 Financials 15 THE SCIENCE MEDIA CENTRE OF CANADA 1867 St.Laurent Blvd MAIN NUMBERS: PO Box 9724, Station T Ottawa, ON OTTAWA (613) 249-8209 K1G 5A3 CALGARY (403) 456-2109 HALIFAX (902) 442-6909 EMAIL: [email protected] MONTRÉAL (438) 288-3909 FAX: 613-990-3654 VANCOUVER (604) 248-4209 www.sciencemedia.ca GTA (647) 729-1909 INCLUSIVENESS RESPONSIVENESS COLLABORATION CREDIBILITY PERSPECTIVE EFFICIENCY PROACTIVE RELATIONSHIPS OBJECTIVITY RAPID RESPONSE NEUTRALITY CONNECTIONS ACCESSIBILITY ACCURACY TRANSPARENCY DEPTH QUALITY EVIDENCE-BASED VALUE-ADDED Annual Report 2010–2011 1 Inform public debate with evidence-based accurate science. Improve the quality and quantity of reporting in all fields of science. Increased public engagement with science issues through media coverage of science that is accurate, incisive and evidence-based. Public debate and policy decisions will benefit. The vision of the Science Message FROM Media Centre of Canada is to “inform public debate THE CHAIR Of with evidence-based accu- rate science”. Knowing that THE Board science is in everything we are, experience, and will become, the SMCC fills a unique role in terms of bringing science and the media closer together to the benefit of Canadians and public policy decision makers. The Science Media Centre of Canada Media Centre The Science 2 organizational values With the right vision and values, This is where I believe the SMCC Let me take this opportunity to thank our execution of strategy has been can continue to play an important role those organizations and individuals impressive as we close on our first full when it comes to Canada building in who have financially supported the year of operation. -

Curriculum Vitae

Angela Nyhout [email protected] | c: +1-226-338-5241 University of Toronto 252 Bloor St. W., Toronto, ON, Canada, M5S 1V6 EDUCATION Ph.D. in Psychology, University of Waterloo 2015 B.Sc, Honours, Psychology and Physiology, University of Western Ontario 2007 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Toronto May 2017-Present (Parental leave: 2018-2019) Postdoctoral Fellow, Institute of Child Study, University of Toronto Oct 2015-May 2017 Research Intern, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario May-Sept 2015 RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Visiting Postgraduate Researcher, Department of Psychology, University of Sheffield 2008-2009 Research Assistant, Educational and Counselling Psychology, McGill University 2008 Research Assistant, Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario 2008 TEACHING CERTIFICATES Certificate in University Teaching, University of Waterloo 2014 Fundamentals of University Teaching, University of Waterloo 2011 AWARDS AND HONOURS 1. Society for Research in Child Development Travel Award ($500USD) 2017 2. International Convention on Psychological Science Travel Award ($350USD) 2017 3. J. Albrecht Outstanding Young Scientist Award, Society for Text & Discourse ($150USD) 2015 4. Society for Text & Discourse Travel Award ($500USD) 2015 5. Development 2014 Travel Award ($200CAD) 2014 6. Best Student Paper on a Cognitive Science Topic – Cognitive Science Society ($250USD) 2013 7. Computational Models of Narrative Travel Award ($1,250USD) 2013 8. SRCD Student Travel Award ($300USD) 2013 RESEARCH GRANTS & FUNDING All amounts are in Canadian dollars 1. SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellowship Award ($81,000) 2017-2019 Project: Informal contexts for supporting children’s ability to control variables in the service of scientific inquiry. 2. Co-PI, SSHRC Connection Grant ($8,754) 2016 Project: Interdisciplinary Workshop on Counterfactual Reasoning 3. -

Department of Chemistry 2015 Newsletter June 2015, Issue 1

Department of Chemistry 2015 Newsletter June 2015, Issue 1 A Message from the Head Why a newsletter? This is (to my knowledge) a first for our department, and long overdue. There is so much going on in our department year after year, it should be celebrated publicly, and not just in a 140-character tweet. This newsletter can't capture every moment of the past year, but should give anyone an idea of the kind of department we have built. I hope this snapshot of Chemistry in 2014-15 holds interest for all of our extended chemical family; everyone from prospective students, to current department members, to retirees and alumni from the days when Thorvaldson and Spinks were professors, not buildings. If you have read any of the pages on our website on the history of the department you will know Dr. David Palmer that Chemistry has been one of the strengths of the University of Saskatchewan from its earliest Head of Department days. We are carrying on that tradition, as we have gone through two reviews of programs in the past two years and been assessed as providing an outstanding learning and research environment for faculty, trainees and students. The TransformUs prioritization process, though controversial, correctly pointed to Chemistry as having one of the top sets of programs on campus. This year's Graduate Program Review also found our department to be a thriving research and training enterprise. As a result, we have won the right to expand our faculty and staff complements for the first time in many years. -

Tuesday, June 1, 2021 Senate Meeting Agenda

SENATE MEETING AGENDA TUESDAY, JUNE 1, 2021 SENATE MEETING AGENDA Tuesday, June 1, 2021 Via ZOOM Video Conferencing 5:00 p.m. Committee of the Whole Discussion: Mental Health and Wellbeing 6:00 p.m. Senate Meeting starts 1. Call to Order/Establishment of Quorum 2. Land Acknowledgement "Toronto is in the 'Dish With One Spoon Territory’. The Dish With One Spoon is a treaty between the Anishinaabe, Mississaugas and Haudenosaunee that bound them to share the territory and protect the land. Subsequent Indigenous Nations and peoples, Europeans and all newcomers have been invited into this treaty in the spirit of peace, friendship and respect." 3. Approval of the Agenda Motion: That Senate approve the agenda for the June 1, 2021 meeting. 4. Announcements Pages 1-27 5. Minutes of the Previous Meeting Motion: That Senate approve the minutes of the May 4, 2021 meeting. 6. Matters Arising from the Minutes 7. Correspondence 8. Reports Pages 28-35 8.1 Report of the President 8.1.1 President’s Update __________________________________________________________________________________________ Pages 36-37 8.2 Communications Report __________________________________________________________________________________________ 8.3 Report of the Secretary Pages 38-41 8.3.1 Standing Committees of Senate: AGPC and SPC membership 8.3.2 RGSU seat on Senate for the 2021-2022 academic year __________________________________________________________________________________________ Pages 42-94 8.4 Committee Reports 8.4.1 Report #W2021-5 of the Academic Standards Committee (ASC): K. MacKay __________________________________________________________________________________________ Pages 42-50 8.4.1.1. Periodic Program Review for Electrical Engineering – Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science Motion: That Senate approve the Periodic Program Review for Electrical Engineering – Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science. -

BOARD of GOVERNORS Monday, March 30, 2015 Jorgenson Hall – JOR 1410 380 Victoria Street 5:00 P.M

BOARD OF GOVERNORS Monday, March 30, 2015 Jorgenson Hall – JOR 1410 380 Victoria Street 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. AGENDA TIME ITEM PRESENTER ACTION Page 5:00 1. IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION (Board Members Only) 5:05 2. IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION (Senior Management Invited) END OF IN-CAMERA SESSION 5:35 6. INTRODUCTION 6.1 Chair’s Remarks Janice Fukakusa Information 6.2 Approval of the March 30, 2015 Agenda Janice Fukakusa Approval 5:40 7. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Sheldon Levy Information 48-54 7.1 Enactus Presentation Stefany Nieto and Information 55-80 Benjamin Canning, Enactus 7.2 Toronto is Basketball Information i. Canadian Intramural Sports (CIS) Heather Lane Vetere ii. Pan Am Games Erin McGinn 5:55 8. SECRETARY’S REPORT 8.1 Board Election Report Update Julia Shin Doi Information 81-87 6:00 9. REPORT FROM THE PROVOST AND VICE Mohamed Lachemi Information 88-94 PRESIDENT ACADEMIC 9.1 Academic Administrative Appointment Mohamed Lachemi Information 95 9.2 Referendum Request from the Ryerson Science Mohamed Lachemi Approval 96-108 Society Heather Lane Vetere Ana Sofia Vargas- Garza Adrian Popescu 6:20 10. REPORT FROM THE CHAIR OF THE FINANCE Mitch Frazer Information COMMITTEE 10.1 Ryerson Student Union Fees Presentation Jesse Root, Vice Information 109-116 President, Education RSU 6:35 10.2 Budget 2015-16: Part One – Environmental Scan Mohamed Lachemi Information 117-134 Paul Stenton 10.3 Budget 2015-16: Part Two - Fees Context Paul Stenton Information 135-170 11. CONSENT AGENDA 11.1 Approval of the Minutes of January 26, 2015 and Janice Fukakusa Approval 171-174 the Minutes of the March 5, 2015 Special Meeting of the Board 11.2 Third Quarter Financial Results Janice Winton Approval 175-182 11.3 Review of Revenue and Expenditures for New Paul Stenton Approval 183-189 Bachelor of Arts in Language and Intercultural Relations 11.4 Review of revenue and expenditures for new Paul Stenton Approval 190 Professional Masters Diploma in Energy and Innovation 11.5 Fiera Capital Report December 31, 2014 Janice Winton Information 191-211 12. -

In This Issue

UofT MathTHE NEWSLETTER OF THE U of T MATHEMATICS DEPARTMENT 2015: YEAR IN REVIEW In this issue James Arthur wins Wolf Prize Centre for Applied Mathematics Announced Faculty members provide 2015 IMO team training In Memorium: Andres del Junco, Arthur Sherk and Ida Bulat Undergraduate, graduate, outreach, and IT updates This Departmental Newsletter motivated both by research opportunities as well as Fromis filled withthe warm welcomes, theChair need to help our students equip themselves for the hearty congratulations broader manifestations of mathematics in society. The and fond farewells and Centre for Applied Mathematics is meant to focus those remembrances. This past ideas into a concrete form. year has seen us welcome six new faculty members from a Initially, the Centre will be based around six research wide variety of backgrounds clusters. The clusters are: and the awarding of five prestigious awards including • The mathematical analysis of risk two Sloans, a Royal Society • Applications of mathematics to Information membership and a Wolf Prize. It has also seen a Technology dramatic increase in our undergraduate enrolment • Mathematics of imaging numbers, which now makes MAT the second largest • The mathematics of fluids program of study in the Faculty of Arts and Science. • Optimal Transport We are also in the process of moving to a new building • The mathematics of big data where our lecturers and graduate students can finally have space to spread out and collaborate, and where we The first two already have a lab associated with them, can launch our Centre for Applied Mathematics. namely RiskLab and GANITA. The Centre should enable us to establish labs for the other themes as well. -

Urban Psychologist (Fall 2014).Pdf

Department of Psychology Newsletter | Ryerson University Fall 2014 Volume 7: Issue 1 THE URBAN PSYCHOLOGIST IN THIS ISSUE: Chair’s Corner Undergrad Program Updates ................................2 Grad Program Updates, PGSA Update ..................2 With the 2014-2015 academic year underway, the summer has given way to an exciting PSA Update, ERA Awards .......................................3 fall term, with over 130 new students joining our Psychology BA program. We also Psychology in the News .........................................3 welcomed 17 new MA students and 4 new PhD students (and 9 more students who Practicum Training in Psych Science ....................4 transitioned from our MA to our PhD). In this issue of UP, you will be introduced to our Russo named Hear the World Chair ......................5 new graduate students, as well as our new Undergraduate Program Assistant (Shadi Recent Research Grants ........................................5 Sibani), two new postdoctoral fellows (Todd Coleman; Syed Noor) and a new assistant Mindfulness Martial Arts .......................................6 Announcements, Awards, Contributions ..............6 professor (Dr. Paul Brunet). A warm Ryerson welcome to all of you! Recent Publications ...............................................7 Since our last issue of UP, members of the Psychology Department have been as busy Psych BA Graduate Andrea Polanco ......................8 Dr. Martin Antony as ever. More than 20 new research grants were received since the spring of 2014, Vanier Winner -

Examples Illustrating the Richness and Reach of EPO in Canada

This is the draft EPO Committee report for LRP2020 Phil Langill (University of Calgary / Rothney Astrophysical Observatory), Frédérique Baron (Université de Montréal), Julie Bolduc-Duval (Discover the Universe / À la découverte de l’Univers), Pierre Chastenay (Université du Québec à Montréal), Mike Chen (University of Victoria), Robert Cockcroft (University of Western Ontario), Kelly Lepo (McGill University), Sharon Morsink (University of Alberta), Magdalen Normandeau (University of New Brunswick), Nathalie Ouellette (Université de Montréal), Nienke van der Marel (NRC Herzberg, Victoria). Introduction The purpose of this report is to try and inform the LRP2020 committee about two aspects of astronomy Education and Public Outreach (EPO) in Canada. The first is the richness and reach of EPO in Canada. The second is the role of CASCA’s EPO committee in this endeavour. PART 1 – Examples illustrating the Richness and Reach of EPO in Canada 1) EPO Activities across demographics. Audience Examples of Canadian Astronomy EPO K-12 Students School visits by Astronomers Summer camps University of Alberta USchool McGill Space Explorers Let’s Talk Science K-12 Teachers Discover the Universe Alberta Science Network McGill Teacher Inquiry Institute Girls and Underrepresented Youth University of Alberta WISEST Dalhousie University Imhotep's Legacy Academy McGill Girls in Physics Day Families with young children Science Rendezvous Eureka! Festival College and University students McGill Physics Hackathon Adults interested in science Talks at RASC Centres -

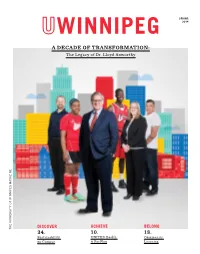

A DECADE of TRANSFORMATION —INSIDE & out the Legacy of Dr

SPRING WINNIPEG 2014 A DECADE OF TRANSFORMatION: The Legacy of Dr. Lloyd Axworthy DISCOVER ACHIEVE BELONG THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG MAGAZINE 34. 10. 18. Sustainability UNITED Health Community on Campus & RecPlex Learning Reward yourself. Get the BMO® University of Winnipeg MasterCard.®* Reward yourself with 1 AIR MILES®† reward mile for every $20 spent or 0.5% CashBack® and pay no annual fee1,2. Give something back With every purchase you make, BMO Bank of Montreal® makes a contribution to help support the development of programs and services for alumni, at no additional cost to you. Apply now! 1-800-263-2263 Alumni: bmo.com/winnipeg Student: bmo.com/winnipegspc Call 1-800-263-2263 to switch your BMO MasterCard to a BMO University of Winnipeg MasterCard. 1 Award of AIR MILES reward miles is made for purchases charged to your Account (less refunds) and is subject to the Terms and Conditions of your BMO MasterCard Cardholder Agreement. The number of reward miles will be rounded down to the nearest whole number. Fractions of reward miles will not be awarded. 2 Ongoing interest rates, interest-free grace period, annual fees and all other applicable fees are subject to change. See your branch, call the Customer Contact Center at 1-800-263-2263, or visit bmo.com/mastercard for current rates.® Registered trade-marks of Bank of Montreal. ®* MasterCard is a registered trademark of MasterCard International Incorporated. ®† Trademarks of AIR MILES International Trading B.V. Used under license by LoyaltyOne, Inc. and Bank of Montreal. Docket #: 13-321 Ad or Trim Size: 8.375" x 10.75" Publication: The Journal (Univ of Winnipeg FILE COLOURS: Type Safety: – Alumni Magazine) Description of Ad: U. -

NSERC CREATE Training Program in Arctic Atmospheric Science Publications Bibliography 1 December 2016

NSERC CREATE Training Program in Arctic Atmospheric Science Publications Bibliography 1 December 2016 Notes: Trainees’ names are underlined. Publications are only included if trainees are co-authors. 1. Refereed Journal Articles Submitted [S1] Belikov, D.A., S. Maksyutov, A. Ganshin, R. Zhuravlev, N.M. Deutscher, D. Wunch, D.G. Feist, R.J. Parker, I. Morino, K. Strong, Y. Yoshida, A. Bril, S. Oshchepkov, R. Kivi, H. Boesch, D. Griffith, M.K. Dubey, W. Hewson, J. Mendonca, J. Notholt, M. Schneider, R. Sussmann, V. Velazco, and S. Aoki. Study of the footprints of short-term variation in XCO2 observed by TCCON sites using NIES and FLEXPART atmospheric transport models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., doi:10.5194/acp-2016-201, in review, 2016. Submitted 8 March 2016. [S2] Li, Z., Y. Li and A.H. Manson. Causes of 2015 Summer Drought in the Canadian Prairies. Submitted to Environmental Research Letters, May 2016. [S3] Mendonca, J., K. Strong, K. Sung, V.M. Devi, G.C. Toon, D. Wunch and J.E. Franklin. Using High-Resolution Laboratory and Ground-Based Solar Spectra to Assess CH4 Absorption Coefficient Calculations. Submitted to J. Quant. Spectrosc. Rad. Transfer (special issue on Satellite Remote Sensing of the Atmosphere) 21 June 2016. [S4] Wunch, D., P.O. Wennberg, G. Osterman, B. Fisher, B. Naylor, C.M. Roehl, C. O’Dell, L. Mandrake, C. Viatte, D.W.T. Griffith, N.M. Deutscher, V.A. Velazco, J. Notholt, T. Warneke, C. Petri, M. De Maziere, M.K. Sha, R. Sussmann, M. Rettinger, D. Pollard, J. Robinson, I. Morino, O. Uchino, F. -

Upper School Summer Opportunities Guide 2019-2020

Upper School Summer Opportunities Guide 2019-2020 This document contains information about a wide variety of programs for students to explore, including pre-university academic experiences and summer enrichment opportunities. TABLE OF CONTENTS CANADA 2 Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences & Languages 2 Business, Entrepreneurship & Innovation 4 Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics 4 Visual & Performing Arts 8 Experiential Education & Adventure 9 University Preparatory 11 Service & Work Experience 11 UNITED STATES 13 Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences & Languages 13 Business, Entrepreneurship & Innovation 13 Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics 14 Visual & Performing Arts 15 Summer Program at the Madison Theatre At Molloy College 15 Experiential Education & Adventure 17 University Preparatory 17 INTERNATIONAL 20 Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences & Languages 20 Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics 21 Visual & Performing Arts 22 Experiential Education & Adventure 23 University Preparatory 24 Service & Work Experience 26 PAGE 1 CANADA Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences & Languages Encounters with Canada Encounters With Canada is a unique opportunity for Canadian teens to meet Where: Ottawa, other young people from across the country. Spend an adventure-filled week in ON your nation’s capital! Check out future career options, discover your country, and When: Year Round share your hopes and dreams. For 36 years, EWC has delivered a rich and varied, bilingual program. Who: Age 14-17 ewc-rdc.ca/pub/en Forum for Young Canadians Where: Ottawa, Forum is a one-week leadership opportunity for smart, engaged and opinionated ON participants. Students will have a chance to recreate parliament for a week in Ottawa. Students will go deep inside Canadian politics and public affairs and see When: Selections what running the country looks like up close.