Drum Rhythms and Golden Scriptures: Reasons for Mormon Conversion Within Haiti’S Culture of Vodou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moroni: Angel Or Treasure Guardian? 39

Mark Ashurst-McGee: Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? 39 Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? Mark Ashurst-McGee Over the last two decades, historians have reconsidered the origins of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the context of the early American tradition of treasure hunting. Well into the nineteenth century there were European Americans hunting for buried wealth. Some believed in treasures that were protected by magic spells or guarded by preternatural beings. Joseph Smith, founding prophet of the Church, had participated in several treasure-hunting expeditions in his youth. The church that he later founded rested to a great degree on his claim that an angel named Moroni had appeared to him in 1823 and showed him the location of an ancient scriptural record akin to the Bible, which was inscribed on metal tablets that looked like gold. After four years, Moroni allowed Smith to recover these “golden plates” and translate their characters into English. It was from Smith’s published translation—the Book of Mormon—that members of the fledgling church became known as “Mormons.” For historians of Mormonism who have treated the golden plates as treasure, Moroni has become a treasure guardian. In this essay, I argue for the historical validity of the traditional understanding of Moroni as an angel. In May of 1985, a letter to the editor of the Salt Lake Tribune posed this question: “In keeping with the true spirit (no pun intended) of historical facts, should not the angel Moroni atop the Mormon Temple be replaced with a white salamander?”1 Of course, the pun was intended. -

Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

DIALOGUE PO Box 1094 Farmington, UT 84025 electronic service requested DIALOGUE 52.3 fall 2019 52.3 DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought EDITORS DIALOGUE EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT a journal of mormon thought ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT FICTION Jennifer Quist, Edmonton, Canada POETRY Elizabeth C. Garcia, Atlanta, GA IN THE NEXT ISSUE REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan Papers from the 2019 Mormon Scholars in the INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS Humanities conference: “Ecologies” HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT A sermon by Roger Terry FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT Karen Moloney’s “Singing in Harmony, Stitching in Time” ART Andi Pitcher Davis, Orem, UT BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF Join our DIALOGUE! BUSINESS MANAGER Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT PUBLISHER Jenny Webb, Woodinville, WA Find us on Facebook at Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought COPY EDITORS Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI Follow us on Twitter @DialogueJournal Jared Gillins, Washington DC PRINT SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS EDITORIAL BOARD ONE-TIME DONATION: 1 year (4 issues) $60 | 3 years (12 issues) $180 Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT Becky Reid Linford, Leesburg, VA Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA RECURRING DONATION: Verlyne Christensen, Calgary, AB Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA $10/month Subscriber: Receive four print issues annually and our Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Taylor Petrey, Kalamazoo, MI Subscriber-only digital newsletter Ignacio M. -

Automatic Writing and the Book of Mormon: an Update

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTOMATIC WRITING AND THE BOOK OF MORMON: AN UPDATE Brian C. Hales At a Church conference in 1831, Hyrum Smith invited his brother to explain how the Book of Mormon originated. Joseph declined, saying: “It was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.”1 His pat answer—which he repeated on several occasions—was simply that it came “by the gift and power of God.”2 Attributing the Book of Mormon’s origin to supernatural forces has worked well for Joseph Smith’s believers, then as well as now, but not so well for critics who seem certain natural abilities were responsible. For over 180 years, several secular theories have been advanced as explanations.3 The more popular hypotheses include plagiarism (of the Solomon Spaulding manuscript),4 collaboration (with Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, etc.),5 1. Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 23. 2. “Journal, 1835–1836,” in Journals, Volume. 1: 1832–1839, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 89; “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 5, Mar. 1, 1842, 707. 3. See Brian C. Hales, “Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study,” BYU Studies 58, no. -

The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.•Łs Â

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Student Writing Award Winners Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 12-2013 Leveraging Doubt: The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.‟s “Mormonism‟s Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview” on Mormon Thought Chad L. Nielsen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_stwriting Recommended Citation Nielsen, Chad L., "Leveraging Doubt: The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.'s "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview"" (2013). Arrington Student Writing Award Winners. This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Student Writing Award Winners by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leveraging Doubt Leveraging Doubt: The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.‟s “Mormonism‟s Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview” on Mormon Thought Chad L. Nielsen Utah State University 1 Leveraging Doubt The most exciting single event of the years I [Leonard J. Arrington] was church historian occurred on June 9, 1978, when the First Presidency announced a divine revelation that all worthy males might be granted the priesthood…. Just before noon my secretary, Nedra Yeates Pace, telephoned with remarkable news: Spencer W. Kimball had just announced a revelation that all worthy males, including those of African descent, might be ordained to the priesthood. Within five minutes, my son Carle Wayne telephoned from New York City to say he had heard the news. I was in the midst of sobbing with gratitude for this answer to our prayers and could hardly speak with him. -

GENERAL HANDBOOK Serving in the Church of Jesus Christ Jesus of Church Serving in The

GENERAL HANDBOOK: SERVING IN THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2020 2020 SAINTS • JULY GENERAL HANDBOOK: SERVING IN THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST LATTER-DAY GENERAL HANDBOOK Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints JULY 2020 JULY 2020 General Handbook: Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 2020 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. Version: 7/20 PD60010241 000 Printed in the United States of America Contents 0. Introductory Overview . xiv 0.0. Introduction . xiv 0.1. This Handbook . .xiv 0.2. Adaptation and Optional Resources . .xiv 0.3. Updates . xv 0.4. Questions about Instructions . xv 0.5. Terminology . .xv 0.6. Contacting Church Headquarters or the Area Office . xv Doctrinal Foundation 1. God’s Plan and Your Role in the Work of Salvation and Exaltation . .1 1.0. Introduction . 1 1.1. God’s Plan of Happiness . .2 1.2. The Work of Salvation and Exaltation . 2 1.3. The Purpose of the Church . .4 1.4. Your Role in God’s Work . .5 2. Supporting Individuals and Families in the Work of Salvation and Exaltation . .6 2.0. Introduction . 6 2.1. The Role of the Family in God’s Plan . .6 2.2. The Work of Salvation and Exaltation in the Home . 9 2.3. The Relationship between the Home and the Church . 11 3. Priesthood Principles . 13 3.0. Introduction . 13 3.1. Restoration of the Priesthood . -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

William Smith, Isaach Sheen, and the Melchisedek & Aaronic Herald

William Smith, Isaach Sheen, and the Melchisedek & Aaronic Herald by Connell O'Donovan William Smith (1811-1893), the youngest brother of Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, was formally excommunicated in absentia from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on October 19, 1845.1 The charges brought against him as one of the twelve apostles and Patriarch to the church, which led to his excommunication and loss of position in the church founded by his brother, included his claiming the “right to have one-twelfth part of the tithing set off to him, to be appropriated to his own individual use,” for “publishing false and slanderous statements concerning the Church” (and in particular, Brigham Young, along with the rest of the Twelve), “and for a general looseness and recklessness of character which is ill comported with the dignity of his high calling.”2 Over the next 15 years, William founded some seven schismatic LDS churches, as well as joined the Strangite LDS Church and even was surreptitiously rebaptized into the Utah LDS church in 1860.3 What led William to believe he had the right, as an apostle and Patriarch to the Church, to succeed his brother Joseph, claiming authority to preside over the Quorum of the Twelve, and indeed the whole church? The answer proves to be incredibly, voluminously complex. In the research for my forthcoming book, tentatively titled Strange Fire: William Smith, Spiritual Wifery, and the Mormon “Clerical Delinquency” Crises of the 1840s, I theorize that William may have begun setting up his own church in the eastern states (far from his brother’s oversight) as early as 1842. -

J. Kirk Richards

mormonartist Issue 1 September 2008 inthisissue Margaret Blair Young & Darius Gray J. Kirk Richards Aaron Martin New Play Project editor.in.chief mormonartist Benjamin Crowder covering the Latter-day Saint arts world proofreaders Katherine Morris Bethany Deardeuff Mormon Artist is a bimonthly magazine Haley Hegstrom published online at mormonartist.net and in print through MagCloud.com. Copyright © 2008 Benjamin Crowder. want to help? All rights reserved. Send us an email saying what you’d be Front cover paper texture by bittbox interested in helping with and what at flickr.com/photos/31124107@N00. experience you have. Keep in mind that Mormon Artist is primarily a Photographs pages 4–9 courtesy labor of love at this point, so we don’t Margaret Blair Young and Darius Gray. (yet) have any money to pay those who help. We hope that’ll change Paintings on pages 12, 14, 17–19, and back cover reprinted soon, though. with permission from J. Kirk Richards. Back cover is “Pearl of Great Price.” Photographs on pages 2, 28, and 39 courtesy New Play Project. Photograph on pages 1 and 26 courtesy Vilo Elisabeth Photography, 2005. Photograph on page 34 courtesy Melissa Leilani Larson. Photograph on page 35 courtesy Gary Elmore. Photograph on page 37 courtesy Katherine Gee. contact us Web: mormonartist.net Email: [email protected] tableof contents Editor’s Note v essay Towards a Mormon Renaissance 1 by James Goldberg interviews Margaret Blair Young & Darius Gray 3 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder J. Kirk Richards 11 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder Aaron Martin 21 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder New Play Project 27 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder editor’snote elcome to the pilot issue of what will hope- fully become a longstanding love affair with the Mormon arts world. -

Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2

Episode 27 Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2 NARRATOR: This is Stories from General Conference, volume two, on the topic of Priesthood Power. You are listening to the Mormon Channel. Worthy young men in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have the privilege of receiving the Aaronic Priesthood. This allows them to belong to a quorum where they learn to serve and administer in some of the ordinances of the Church. In the April 1997 General Priesthood Meeting, Elder David B. Haight reminisced about his youth and how the priesthood helped him progress. (Elder David B. Haight, Priesthood Session, April 1997) “Those of you who are young today--and I'm thinking of the deacons who are assembled in meetings throughout the world--I remember when I was ordained a deacon by Bishop Adams. He took the place of my father when he died. My father baptized me, but he wasn't there when I received the Aaronic Priesthood. I remember the thrill that I had when I became a deacon and now held the priesthood, as they explained to me in a simple way and simple language that I had received the power to help in the organization and the moving forward of the Lord's program upon the earth. We receive that as 12-year-old boys. We go through those early ranks of the lesser priesthood--a deacon, a teacher, and then a priest--learning little by little, here a little and there a little, growing in knowledge and wisdom. That little testimony that you start out with begins to grow, and you see it magnifying and you see it building in a way that is understandable to you. -

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

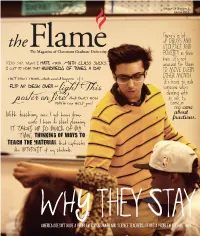

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

Reflections on a Lifetime with the Race Issue

SUNSTONE Twenty-five Years after the Revelation—Where Are We Now? REFLECTIONS ON A LIFETIME WITH THE RACE ISSUE By Armand L. Mauss HIS YEAR WE ARE COMMEMORATING THE resolution was forthcoming when the Presidency decided that twenty-fifth anniversary of the revelation extending the the benefit of the doubt should go to the parties involved. In due T priesthood to “all worthy males” irrespective of race or course, the young couple was married in the temple, but the res- ethnicity. My personal encounter with the race issue, however, olution came too late to benefit Richard. goes back to my childhood in the old Oakland Ward of My own wife Ruth grew up in a family stigmatized by the California. In that ward lived an elderly black couple named LDS residents of her small Idaho town because her father’s aunt Graves, who regularly attended sacrament meeting but (as far in Utah had earlier eloped with a black musician named as I can remember) had no other part in Church activities. Tanner in preference to accepting an arranged polygamous Everyone in the ward seemed to treat them with cordial dis- marriage. Before Ruth’s parents could be married, the intended tance, and periodically Brother Graves would bear his fervent bride (Ruth’s mother) felt the need to seek reassurance from testimony on Fast Sunday. I could never get a clear under- the local bishop that the family into which she was to marry standing from my parents about what (besides color) made was not under any divine curse because of the aunt’s black them “different,” given their obvious faithfulness. -

The Pro-Democracy Faith Movement Prominent Religious Leaders Reflect on the Meaning of Democracy

JIM WATSON/STAFF JIM The Pro-Democracy Faith Movement Prominent Religious Leaders Reflect On the Meaning of Democracy Maggie Siddiqi, Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons, and Carol Lautier February 2021 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 3 The pro-democracy faith movement 6 The religious right’s anti-democratic turn 8 The values of the pro-democracy faith movement 9 Building an inclusive, democratic movement for a more inclusive democracy 10 Centering the experiences of Black Americans 12 Grounding democracy in a shared sense of community 13 Being political but nonpartisan 16 Meeting the urgency of the moment 19 Conclusion 20 About the authors 20 Acknowledgments 21 Appendix 24 Endnotes Introduction and summary This report was developed through a project with Auburn Seminary, which for more than 200 years has equipped leaders of faith and moral courage who are on the front lines fighting for the health and wholeness of U.S. society. The past year has been an incredible test for American democracy. The coronavirus crisis not only crippled America’s public health and economy, but it also necessitated new ways of voting in a presidential election. This incited new tactics for voter sup- pression that compounded long-standing efforts to hobble the voting power of com- munities of color. The electoral process was further compromised by a campaign of unfounded accusations of voter fraud. Then, following the election in November, the former president and certain factions of his allies attempted to overturn the results. Former President Trump was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for his role in inciting the deadly January 6 insurrection at the U.S.