General Englishsemester-V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Militants Killed in Overnight Encounter: Police

th 24 Friday 12 March | 27 Rajab | 1442 Hijri | Vol:24 | Issue: 59 | Pages:12 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net twitter.com / kashmirobserver facebook.com/kashmirobserver Postal Regn: L/159/KO/SK/2014-2016 3 CITY 7 SRINAGAR FACING A 11 SPORTS GARBAGE CRISIS ARRANGEMENTS FOR SHAB-E-MEHRAJ INDIA FOOTBALL CAPTAIN SUNIL Srinagar City, the summer capital CHHETRI TESTS POSITIVE FOR COVID-19 CONGREGATION AT HAZRATBAL REVIEWED of Kashmir is famous worldwide for HINK Mayor Srinagar Municipal Corporation Junaid Azim. Mattu along T its natural environment, gardens, Indian football team captain and star striker Sunil with Commissioner of the Corporation Athar Amir Khan Thursday waterfronts, and houseboats. Emperor Chhetri on Thursday said he has tested positive for visited Dargah Hazratbal Mosque and oversaw the arrangements Jahangir (a Mughal king in the 17th COVID-19, a development that is set to rule him... Widom Govt Begins 2 Militants Killed Process To MeT Predicts Downpour For 3 More Days Beginnings are such Appoint New VCs Snowfall In Upper Reaches Of Kashmir, Rains Continue In Plains delicate times. In Overnight —Frank Herbert Agencies Agencies SRINAGAR: Authorities have SRINAGAR: Gulmarg and other Encounter: Police initiated a process for appoint- reaches of Kashmir Valley re- ment of new vice chancellors ceived fresh snowfall while in Jammu and Kashmir uni- rains continued to lash plains versities where term of Vice amid weatherman’s prediction Chancellors have ended or are for “light to moderate rain and nearing completion. snowfall for next 36 hours. LG Greets People There are around 11 universi- A meteorological depart- On Shab-e-Meraj ties in Jammu and Kashmir in- ment official said that Gulmarg, cluding two central universities. -

(Ms) Membership No: Res: Mobile: Email

SUPREME COURT BAR ASSOCIATION Name & Address Name & Address 1 Wangmo,Rinchen (Ms) 5 A. Roopashri (Mrs.) Membership no: W-00060 Membership no: A-00121 Res: H.No-84, Block-B, Sector A-9, Pocket-1,Narela, Res: 3/2, St. Johns Road,, Shivan Chetty Garden Post, Delhi 110040 Bangalore 560042 Mobile: 8826232720 Tel: 080-25549660 Email: [email protected] Off: 3/2, St. Johns Road,, Shivan Chetty Garden Post, Bangalore 560042 Tel: 080-25307104 2 A. Hanumantha Reddy Mobile: 9886012342 Email: [email protected] Membership no: A-00103 Res: Plot no.28, Vivekananda Enclave, Road No.2, 6 A.Mohan Doss Banjara Hills, Hyderabad, AP 500034 Tel: 040-23744322 Membership no: A-00094 Mobile: 09849536633 Email: [email protected] Res: No-13/2, Khan Street, Choolaimedu, Chennai 600094 Tel: 044-23741149 3 A. Kalamegam V. Arumugam Ch: 71, Law Chamber, Madras High Court, Chennai 600094 Membership no: A-00090 Tel: 044-23741149 Mobile: 09884043335 Res: Old No-3, New No-7, Mosque Street, Chepauk, Channai 600005 Tel: 044-28552939 7 A.S Naushad Ch: 153, Additional Law Charmber, Madras High Court, Madras Membership no: A-00175 Mobile: 9840062370 Email: [email protected] Res: Ishel Near.B.H.S, Attingal, Trivandrum, Kerala 695101 Off: Flat No77, Tower No-13, 4th Floor,, Supreme 4 A. Raja Enlclave, M.V. Ph-1, Delhi Mobile: 9847130707 A-00811 Membership no: Email: [email protected] Res: A-33, Gulmohar Park, New Delhi 110049 Tel: 26531222-333 8 A.S. Rao Mobile: 9013180381,9999864553 Membership no: A-00575 Email: [email protected] Res: H.No.27, 3rd floor, Street No.7,, Pratap Nagar, Mayur Vihar Phase-I,, New Delhi Tel: 011-22756891 Ch: 411, M.C. -

Building a New Kashmir: Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad and the Politics of State-Formation in a Disputed Territory (1953-1963)

Building a New Kashmir: Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad and the Politics of State-Formation in a Disputed Territory (1953-1963) by Hafsa Kanjwal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in The University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Professor Kathryn Babayan Professor Fatma Muge Gocek © Hafsa Kanjwal 2017 [email protected] ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5879-9906 Table of Contents Abstract iii Introduction 1 Chapter One: State-led Developmentalism and the Pursuit of Progress 44 Chapter Two: Creating a Modern Kashmiri Subject: Education, Secularization and its Discontents 97 Chapter Three: Jashn-e-Kashmir: Patronage and the Institutionalization of a Cultural Intelligentsia 159 Chapter Four: The State of Emergency: State Repression, Political Dissent and the Struggle for Self-Determination 205 Chapter Five: Remembering Naya Kashmir in Post Militancy Srinagar 249 Conclusion 304 Bibliography 310 ii Abstract This dissertation is a historical study of the early postcolonial period in the Indian- administered state of Jammu and Kashmir (1953-63). It traces the trajectory of “Naya [New] Kashmir,” a leftist manifesto of the National Conference (NC). The NC was a secular nationalist Kashmiri political party that came to power in the state in 1947, in the aftermath of Partition and the accession of Kashmir to India. This dissertation recuperates the relevance of Naya Kashmir during the rule of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed (1953-63), the second Prime Minister of the state. Naya Kashmir originated as a progressive project of state and socio-cultural reform, emanating from the particular context of the Jammu and Kashmir princely state in the late colonial period. -

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

Kalra, V. and Shalini, S. (Eds.) (2016) State Of

State of Subversion This volume looks at the interface between ideology, religion and culture in Punjab in the 20th century, spanning from colonial to post-colonial times. Through a re-reading of the history of Punjab and of Punjabi migrant networks the world over, it interrogates the term ‘radicalism’ and its relationship with terms such as ‘militancy’, ‘terrorism’ and ‘extremism’ in the context of Punjab and elsewhere during the period; explores the relationship between left and religious radicalism—such as the Ghadar movement and the Akalis – and the continuing role of radical movements from British Punjab to the independent states of India and Pakistan. Expanding the dimensions on the study of Punjab and its historical impact in the South Asian region, this book will interest scholars and students of modern Indian history, politics and sociology. Virinder S. Kalra is Senior Lecturer in sociology at the University of Manchester. He is the author of Sacred and Secular Musics: A Postcolonial Approach (2014). Widely published, his areas of research include Punjabi popular culture, British racism and themes in creative resistance. Shalini Sharma is Lecturer in colonial and postcolonial history at Keele University. She has written on radical politics in Punjab and is currently working on Indian intellectuals and the USA. Introduction i South Asian History and Culture Series Editors: David Washbrook, University of Cambridge, UK Boria Majumdar, University of Central Lancashire, UK Sharmistha Gooptu, South Asia Research Foundation, India Nalin Mehta, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore This series brings together research on South Asia in the humanities and social sciences, and provides scholars with a platform covering, but not restricted to, their particular fields of interest and specialization. -

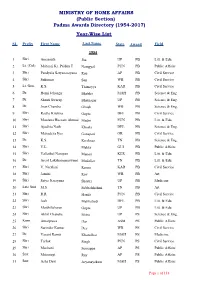

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt.