A Homeless Educators Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

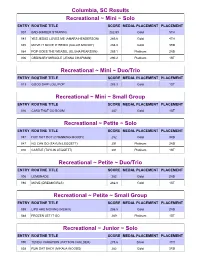

Columbia, SC Results Recreational ~ Mini ~ Solo ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT

Columbia, SC Results Recreational ~ Mini ~ Solo ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 007 BAD (KIMBER STRAWN) 282.93 Gold 5TH 083 YES JESUS LOVES ME (AMARA HENDERSON) 285.6 Gold 4TH 085 MOVE IT MOVE IT REMIX (KALLIE MOODY) 286.8 Gold 3RD 084 POP GOES THE WEASEL (ELIJHA PEARSON) 289.1 Platinum 2ND 006 ORDINARY MIRACLE (JENNA CHAPMAN) 290.2 Platinum 1ST Recreational ~ Mini ~ Duo/Trio ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 013 GOOD SHIP LOLLIPOP 285.3 Gold 1ST Recreational ~ Mini ~ Small Group ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 016 CARS THAT GO BOOM 287 Gold 1ST Recreational ~ Petite ~ Solo ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 087 HOT HOT HOT (CHANNING MOODY) 282 Gold 3RD 047 NO CAN DO (TAYLIN LEGGETT) 291 Platinum 2ND 010 CASTLE (TAYLIN LEGGETT) 291 Platinum 1ST Recreational ~ Petite ~ Duo/Trio ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 008 LEMONADE 282 Gold 2ND 086 MOVE (DREAMGIRLS) 282.8 Gold 1ST Recreational ~ Petite ~ Small Group ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 089 LIPS ARE MOVING (REMIX) 286.5 Gold 2ND 088 FROZEN LET IT GO 289 Platinum 1ST Recreational ~ Junior ~ Solo ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 090 TENDU VARIATION (PAYTON CAULDER) 278.6 Silver 4TH 038 RUN DAT BACK (MIKALA WOODS) 282 Gold 3RD 039 LOOKING FOR HOME (SARIA JORDAN) 287.8 Gold 2ND 040 BABY JUNE (AUBREY MOBLEY) 291 Platinum 1ST Recreational ~ Junior ~ Duo/Trio ENTRY ROUTINE TITLE SCORE MEDAL PLACEMENT PLACEMENT 081 I'M A LADY 288.4 Platinum 1ST Recreational ~ Junior -

Dance Music & Songs

Top 10’s – Dance Music & Songs Dance Music Top 10 50's 1. Chuck Berry – Johnny B Good 2. Dion – Runaround Sue 3. Chubby Checker – Let’s Twist Again 4. Jerry Lee Lewis – Great Balls Of Fire 5. The Beatles – Twist and Shout 6. Big Bopper – Chantilly Lace 7. Elvis Presley – Can’t Help Falling In Love 8. Bill Haley – Rock Around The Clock 9. The Commitments – Mustang Sally 10. The Kingsmen – Louie Louie Top 10 60's or Motown 1. Temptations – Aint To Proud To Beg 2. Aretha Franklin - Respect 3. Stevie Wonder – I Was Made To Love Her 4. Diana Ross – Someday We’ll Be Together 5. Michael Jackson - ABC 6. The Foundations – Build Me Up Buttercup 7. Rolling Stones - Satisfaction 8. Temptations – My Girl 9. Ike and Tina Turner – Proud Mary (newer version) 10 David Sanborn & Babi Floyd - Shotgun Top 10 70's and Disco 1. Beegees - Stayin’ Alive 2. Abba – Dancin’ Queen 3. Grease Megamix 4. Kool and The Gang - Celebration 5. Donna Summer – Last Dance 6. Village People - YMCA 7. KC and The Sunshine Band – That’s The Way 8. Gloria Gaynor – I Will Survive 9. Marvin Gaye – Got To Give It Up 10. Franki Valli - Oh What A Night Top Ten 80's Dance Hits 1. EWF - September 2. George Clinton - Atomic Dog 3. Dead Or Alive – Spin Me Around 4. B52’s – Love Shack 5. Madonna - Holiday 6. GoGo’s – We Got The Beat/Our Lips are Sealed 7. Romantics – What I like About You 8. Billy Idol – Mony Mony 9. Michael Jackson - Thriller 10. -

12/2008 Mechanical, Photocopying, Recording Without Prior Written Permission of Ukchartsplus

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Issue 383 a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, 27/12/2008 mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Number 1 Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 7” Vinyl only Download only Pre-Release For the week ending 27 December 2008 TW LW 2W Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) High Wks 1 NEW HALLELUJAH - Alexandra Burke Syco (88697446252) 1 1 1 1 2 30 43 HALLELUJAH - Jeff Buckley Columbia/Legacy (88697098847) -- -- 2 26 3 1 1 RUN - Leona Lewis Syco ( GBHMU0800023) -- -- 12 3 4 9 6 IF I WERE A BOY - Beyoncé Columbia (88697401522) 16 -- 1 7 5 NEW ONCE UPON A CHRISTMAS SONG - Geraldine Polydor (1793980) 2 2 5 1 6 18 31 BROKEN STRINGS - James Morrison featuring Nelly Furtado Polydor (1792152) 29 -- 6 7 7 2 10 USE SOMEBODY - Kings Of Leon Hand Me Down (8869741218) 24 -- 2 13 8 60 53 LISTEN - Beyoncé Columbia (88697059602) -- -- 8 17 9 5 2 GREATEST DAY - Take That Polydor (1787445) 14 13 1 4 10 4 3 WOMANIZER - Britney Spears Jive (88697409422) 13 -- 3 7 11 7 5 HUMAN - The Killers Vertigo ( 1789799) 50 -- 3 6 12 13 19 FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK - The Pogues featuring Kirsty MacColl Warner Bros (WEA400CD) 17 -- 3 42 13 3 -- LITTLE DRUMMER BOY / PEACE ON EARTH - BandAged : Sir Terry Wogan & Aled Jones Warner Bros (2564692006) 4 6 3 2 14 8 4 HOT N COLD - Katy Perry Virgin (VSCDT1980) 34 -- -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Sugababes Catfights and Spotlights Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sugababes Catfights And Spotlights mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Catfights And Spotlights Released: 2008 Style: Soul, Ballad, Synth-pop, House MP3 version RAR size: 1492 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1821 mb WMA version RAR size: 1701 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 539 Other Formats: MMF MP3 TTA AUD MP1 MIDI FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Girls Alto Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – Scott GarlandArranged By [Brass] – James TreweekEngineer – Dave PalmerKeyboards, Programmed By – Si Hulbert, Si 1 3:11 HulbertMixed By – Tom ElmhirstMixed By [Assistant] – Dan Parry*Producer – Melvin Kuiters, Si HulbertProducer [Vocals] – Mike StevensTrumpet – Graham Russell Written-By – Anna McDonald, Keisha Buchanan, Nicole Jenkinson You On A Good Day Arranged By, Producer – Klas ÅhlundBass, Guitar, Percussion, Piano, Programmed By – Klas ÅhlundEngineer [Vocals, Assistant] – Werner FreistätterHorns – Per 2 3:26 "Ruskträsk" Johansson, Viktor BrobackeMixed By – Jeremy WheatleyMixed By [Assistant] – Richard EdgelerProgrammed By [Additional] – "Phat" Fabe*Written-By – Keisha Buchanan, Klas Åhlund No Can Do Bass, Guitar – George AstasioEngineer [Brass] – Spencer DewingEngineer [Vocals, Assistant] – Xavier StephensonEngineer [Vocals] – Matt LawrenceKeyboards, Programmed By – Jason Pebworth, Jon Shave, Si HulbertKeyboards, Programmed By, 3 3:10 Producer [Additional] – Melvin KuitersMixed By – Jeremy WheatleyMixed By [Assistant] – Richard EdgelerProducer – Si Hulbert, The Invisible MenSaxophone – Jim HuntTrombone – Nichol Thompson*Trumpet -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

Flying Start Children's Centre

Soundwaves Case Study - 2016/2017 Developing language in young children from multi-cultural families Flying Start Children’s Centre To find out about Soundwaves Extra visit www.takeart.org or contact [email protected] A CASE STUDY with Developing language in young children from multi-cultural families Exploring a collaboration between a music specialist and Early Years’ worker Contents THE IDEA Who is behind this? 3 The Objective The Early Years’ Worker – an introduction 4 Sourcing the children’s centre and Early Years’ worker The Music specialist – an introduction 5 Sourcing the music specialist Sourcing the families The setting 6 Establishing the project (written from the MS perspective) 7 What professional development? The activities The chosen songs 8 Duel-Purpose of songs and poems 9 Ethics Collating the evidence Commitment and regular attendance WHAT HAPPENED? 10 Igniting interest in developing new skills (written from the MS perspective) Feedback from parents and children Vocal responses The power of a little instrument 11 I can’t sing! I can’t play! 12 Developing leadership skills 13 Initiating musical objectives through real life activity 14 Initiating language with familiar songs 15 Using resources and visuals 16 Achieving goals The template 17 Collaborative achievement Were the aims of the project fulfilled? 19 The future 20 Acknowledgements 22 Bibliography and appendix 23 2 THE IDEA Who behind this? Soundwaves Extra is an Early Years’ music organisation established to look at how music impacts on, and develops musicality in young children. Soundwaves Extra is funded by Youth Music, which supports, shares and endorses music making, training and resources across the UK. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

The Prospect

THE PROSPECT Written by Eric R. Williams Based on the novel PROSPECT by William Littlefield Contact: Alvaro Donado Workshop Entertainment, LLC 459 Columbus Ave, Suite 248 New York, NY 10024 (646) 827-9829 T (646) 827-9843 F [email protected] INT. 1965 BLACK IMPALA CONVERTIBLE - DAY With a baseball GAME barking from the RADIO, a YOUNG PETE ESTEY - white, late 40s, salt and pepper hair, WORN SPORTS COAT - drives down a country road. Spring, 1975. Windows down. Young Pete thumbs his directions in a TINY NOTEBOOK that sits on top of a worn, folded, road map. The car follows a soft bend in the dirt road and then... A Baseball Field - like baseball fields everywhere - through the windshield. A small, rusty backstop. An old scoreboard. Fans sprinkled on old bleachers. A wooden BAT HITTING A BALL, crisp as the clear blue sky. EXT. BASEBALL FIELD, 1975 - DAY Young Pete STICKS OUT from the crowd - the ONLY WHITE MAN within fifty miles. WHISPERS. Stares awkwardly disguised. Young Pete watches the plate. A GANGLY TEENAGER chokes up on the bat. The pitch - fast and tight - whips past. The kid swings, too late. The PITCHER/COACH - a grown man with arms like cannons - sees Pete as the catcher throws the ball back. COACH Awright, Junior. That’s enough. Take a lap. Cappy! Cappy, get in the box! YOUNG CAPPY HAYNES - big kid, about 18 years old with a confident way and a devilish SMILE - hustles from second base to the plate... eyeing Pete the whole time. Off the plate - Young Cappy RUBS EACH WRIST.. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

Campfire 'Once Upon a Long, Long Time Ago, Our Parents and Grand- Parents Left a Place Called Earth. They Travelled Across the S

file:///F|/rah/Larry%20Niven/Niven,%20Larry%20-%20Dragons%20of%20Heorot.txt Campfire 'Once upon a long, long time ago, our parents and grand- parents left a place called Earth. They travelled across the stars in a ship called Geographic to find paradise. But their paradise turned into a living hell.. .' The campfire jetted white flame as it reached a gum pocket in the horsemane log. The flame held for almost a minute, then died back to glowing coals. A cast-iron skillet balanced on firestones sizzled in the embers. A sudden gust momentarily sent sparks toward the misty night sky and the stars frozen overhead. A dozen wide-eyed youngsters were packed shoulder- tight on makeshift seats of logs and stones, huddled expectantly in the dying firelight. They had waited all their lives for this night. Justin Faulkner's voice growled, caressed, leapt, burned hotter than the ebbing flames. 'From the stars they came,' he stage-whispered, 'seeking to build homes where no human had ever walked. Avalon was a land untamed, stretching beneath a sky strange to human eyes. A para- dise for the taking. These men and women were the best, the smartest and the bravest Earth could offer, two hun- dred chosen from eight billion people. Our parents. They are the Earth Born. But they didn't know the truth about their new world, a truth that you -' his long, sensitive fingers, sculptor's fingers, bunched and stabbed as if each and every child was guilty of unspeakable crimes - 'you Star Born, have never been told .