A Profile of the Economy, Labour Market and Business Structure of Rutland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Casterton Parish Plan 2005

A1 © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Rutland Council District Council Licence No. LA 100018056 With Special thanks to: 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. History 3. Community and household 4. Transport and traffic 5. Crime and community safety 6. Sport and leisure 7. Youth 8. Village church 9. Education 10. Retail services 11. Farming and heritage 12. Conservation and the environment 13. Planning and development 14. Health and social services 15. Information and communication 16. Local councils 17. Conclusion 18. Action plan 3 INTRODUCTION PARISH PLANS Parish plans are part of the “Vital Villages” initiative of the Countryside Agency, run locally through the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland). A Parish Plan should provide a picture of a village, identifying through consultation the concerns and needs of its residents. From the plan villages should identify actions to improve the village and the life of the community. The resulting Village Action Plan is then used to inform the County Council, through the Parish Council. Parish Plans have a statutory place in local government. GREAT CASTERTON PARISH PLAN Great Casterton’s Parish Plan started with a meeting of villagers in June 2002. There was particular interest because of a contentious planning decision imposed by the County Council on the village. The Community Development Officer for Rutland, Adele Stainsby, explained the purpose of the plan and the benefits for the village. A committee was formed, and a constitution drawn up. The Parish Council promised a small initial grant while an application for Countryside Agency funding was prepared. The money granted was to be balanced by the voluntary work of villagers. -

Digital Rutland Strategy 2019-2022

Digital Rutland Strategy 2019-2022 Version V1.0 This page is left intentionally blank 1 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.0 Our Vision ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Overview - Our Digital Strategy Aims ......................................................................................... 4 3.0 Aim 1: Building on Superfast Broadband Connectivity ............................................................ 5 4.0 Aim 2: Accelerating Full Fibre Coverage in Rutland ................................................................ 7 5.0 Aim 3: Facilitating 4G and 5G Mobile Broadband Networks ................................................. 10 6.0 Aim 4: Connecting Businesses to New Opportunities ........................................................... 15 7.0 Aim 5: Enabling Digital Delivery and Service Transformation .............................................. 17 8.0 Aim 6: Ensuring Digital Inclusion ............................................................................................... 18 9.0 Strategic Alignment ..................................................................................................................... 22 10.0 Expected Benefits ..................................................................................................................... 25 11.0 Next -

RISE up STAND out This Guide Should Cover What You Need to Know Before You Apply, but It Won’T Cover Everything About College

RISE UP STAND OUT This guide should cover what you need to know before you apply, but it won’t cover everything about College. We 2020-21 WELCOME TO know that sometimes you can’t beat speaking to a helpful member of the VIRTUAL team about your concerns. OPEN Whether you aren’t sure about your bus EVENTS STAMFORD route, where to sit and have lunch or want to meet the tutors and ask about your course, you can Live Chat, call or 14 Oct 2020 email us to get your questions answered. COLLEGE 4 Nov 2020 Remember, just because you can’t visit 25 Nov 2020 us, it doesn’t mean you can’t meet us! 20 Jan 2021 Find out more about our virtual open events on our website. Contents Our Promise To You ..............................4 Childcare ....................................................66 Careers Reference ................................. 6 Computing & IT..................................... 70 Facilities ........................................................ 8 Construction ............................................74 Life on Campus ...................................... 10 Creative Arts ...........................................80 Student Support ....................................12 Hair & Beauty ......................................... 86 Financial Support ................................. 14 Health & Social Care .......................... 90 Advice For Parents ...............................16 Media ........................................................... 94 Guide to Course Levels ......................18 Motor Vehicle ........................................ -

219832 the Old Plough.Indd

AN ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE FRONTED DETACHED DWELLING IN A PRIVATE VILLAGE SETTING, WITH THREE ANCILLARY STONE BARNS AND LANDSCAPED GARDENS the old plough, church street, carlby, stamford, lincolnshire, pe9 4nb AN ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE FRONTED DETACHED DWELLING IN A PRIVATE VILLAGE SETTING, WITH THREE ANCILLARY STONE BARNS AND LANDSCAPED GARDENS the old plough, church street, carlby, stamford, lincolnshire, pe9 4nb Entrance hallway w Sitting room w Dining Kitchen w Study/Play room w Utility w Principal bedroom with en suite w Three further bedrooms w Family bathroom w Driveway & extensive parking w Three ancillary stone barns w Landscaped private gardens Mileage Stamford 6 miles (Trains to Peterborough from 10 mins and Cambridge from 65 mins) w Bourne & Market Deeping 7 miles w Peterborough Railway Station 15 miles (London Kings Cross from 49 mins) Situation Carlby is an attractive small village with a supportive village community, served by Ryhall Primary School, a village with which it often twins for community events. Almost midway between Stamford and Bourne amidst attractive rolling countryside, whilst rural, the village is well connected. The attractive Georgian market towns of Stamford, Bourne and Market Deeping are all within 7 miles of Carlby. For commuters, Stamford’s railway station has hourly train services to Peterborough (connecting to London Kings Cross services) and Cambridge on the Midlands Cross Country Birmingham Airport to Stansted Airport line. Further, the Cathedral City of Peterborough (15 miles) offers a wider range of retail outlets, including the Queensgate Shopping Centre and mainline commuter services to London Kings Cross. Schooling is also well catered for in the area with a choice of private schooling, aside from good state education in Ryhall. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No.199 LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No.199 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT ' NO. 199. PW To the Et Hon Merlyn Rees, HP Secretory of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS KOH FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE DISTRICT OF RUTLAND IN THE COUNTY OF LEICESTERSHIRE 1* We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the district of Rutland, in . accordance with the requirements of section 63 oft and Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act, 19?2, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that District. 2* In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60(1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 31 December 1971*- that we were to undertake this review* This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to Rutland Idutrict Council, copies of which were circulated to the Leicestershire County Council, Parish Councils and Parish Meetings, the member of Parliament for the constituency concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press* Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies* 3* Rutland District Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representa- tion for our consideration. When doing so, they were asked to observe the rules laid down in Schedule 11 to the Local Government Act 1972 and the guidelines which we set out in our Report No 6 about the proposed size of the Council and the proposed number of councillors for each ward. -

Introduction Methodology

RYHALL AND BELMESTOPE PARISH SURVEY RESULTS Survey undertaken August/September 2017 Survey results approved and ratified by the Parish Council May 2018 Results published June 2018 Introduction In response to the national need for more housing, Rutland County Council has drawn up a Local Plan for countywide development in the period up to 2036. This will require the addition of 1,700 dwellings. The nine large Rutland villages, of which Ryhall is one, are expected to contribute one-third of this total, i.e. 566 dwellings. Were this spread equally amongst the nine it would require Ryhall to expand by ca. 63 dwellings. Ryhall Parish Council considered formally contributing a Neighbourhood Plan, but following consultation with parishioners instead opted for a simpler Parish Plan. The first stage in this process was to canvass the views of Ryhall and Belmesthorpe residents through a survey. Methodology Accordingly a volunteer working party project team was formed chaired by Dave Amies, including Linda & Simon Davies, Pat Bate and Andrew Nebel, and authorized to undertake the survey. With very significant support from Caroline Adams, Parish Clerk, a review of other Rutland Villages’ neighbourhood planning surveys was undertaken and used to design a questionnaire adjudged specifically suitable to the needs of our villages. In addition, a questionnaire was designed for completion by all year 6 pupils of Ryhall CE Academy. 700 questionnaires were printed and through the kind voluntary assistance of Tony Dolby and Andy Thomas, one was delivered to every dwelling in Ryhall and Belmesthorpe. A total of 217 completed questionnaires were returned from Ryhall residents [a 33% response rate] and 20 from Belmesthorpe [a response rate of 25%] to collection points at the Village Stores, The Library, the School and the Blue Bell public house. -

Landscape Character Assessment of Rutland (2003)

RUTLAND LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT BY DAVID TYLDESLEY AND ASSOCIATES Sherwood House 144 Annesley Road Hucknall Nottingham NG15 7DD Tel 0115 968 0092 Fax 0115 968 0344 Doc. Ref. 1452rpt Issue: 02 Date: 31st May 2003 Contents 1. Purpose of this Report 1 2. Introduction to Landscape Character Assessment 2 3. Landscape Character Types in Rutland 5 4. The Landscape of High Rutland 7 Leighfield Forest 8 Ridges and Valleys 9 Eyebrook Valley 10 Chater Valley 11 5. The Landscape of the Vale of Catmose 15 6. The Landscape of the Rutland Water Basin 18 7. The Landscape of the Rutland Plateau 20 Cottesmore Plateau 21 Clay Woodlands 23 Gwash Valley 24 Ketton Plateau 25 8. The Landscape of the Welland Valley 28 Middle Valley West 28 Middle Valley East 29 Figures and Maps Figure 1 Landscape Character Types and Sub-Areas Figure 2 Key to 1/25,000 Maps Maps 1 - 10 Detailed 1/25,000 maps showing boundaries of Landscape Character Types and Sub-Areas Photographs Sheet 1 High Rutland and Welland Valley Sheet 2 Vale of Catmose and Rutland Water Basin Sheet 3 Rutland Plateau References 1 Leicestershire County Council, 1976, County Landscape Appraisal 2 Leicestershire County Council, 1995 published 2001, Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Landscape and Woodland Strategy 3 Countryside Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage, 2002, Landscape Character Assessment Guidance for England and Scotland 4 Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment and the Landscape Institute, 2002, Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment, Spons 5 Countryside Agency and English Nature, 1997, The Character of England: Landscape Wildlife and Natural Features and Countryside Agency, 1999, Countryside Character Volume 4: East Midlands 6 Department of Environment, 1997 Planning Policy Guidance 7 The Countryside - Environmental Quality and Economic and Social Development RUTLAND LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT DTA 2003 1. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

Uppingham Parish Plan

UPPINGHAM PARISH PLAN OCTOBER 2007 UPPINGHAM PARISH PLAN Introduction In April 2006 a steering group was formed with the support of the Rural Community Council and Uppingham Town Council to prepare a plan for the future of Uppingham. We are grateful to the staff of both Councils for their help and encouragement. The group prepared a questionnaire that was delivered to all households in the town early in 2007. The responses to this questionnaire were analysed and it is relevant that more than 50% of respondents described themselves as retired. The views of the respondents form the plan and it is clear that they like their town and are concerned about changes taking place without consultation. However they accept that if changes must take place such changes take into account their views and the character and history of the town. The plan is to be taken into account by the Town Council, Rutland County Council, National Government and statutory service providers in matters affecting Uppingham. The group has considered it important to provide a background to the plan by reference to history and the town at the present time. We believe all facts to be correct and apologise if there are any errors or omissions. Neil Hermsen – Chairman of the Steering Group A little local history Although Uppingham does not appear in the Domesday Book there is little doubt that a set- tlement existed for many years before the Norman Conquest. The name, deriving from the “Ham of the Yppingas” meaning “people of the upland”, indicates that it came into existence by the early 6th century but the settlement may have come into being even earlier. -

Rutland 1851 Census Returns

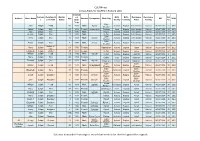

CULPIN-net Census Finds for CULPIN in Rutland 1851 Estimat Surnam Relationshi Marital ed Birth Birth Residence Residence Sch Address Given Name Age Gender Occupation Birth City REF YEAR e p to Head Status Birth County Country Place County No Year Edith John Calpin Head 43 1808 Male Ag Lab Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland HO107-2092 49 1851 Weston Abigail Calpin Wife 41 1810 Female Ag Labs Wife Thorston Notts England Edith Weston Rutland HO107-2092 49 1851 John Calpin Son 15 1836 Male Ketton Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland HO107-2092 49 1851 George Calpin Son 13 1838 Male Ketton Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland HO107-2092 49 1851 Edith Henry Calpin Son 10 1841 Male Scholar Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland HO107-2092 49 1851 Weston Edith Amos Calpin Son 7 1844 Male Scholar Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland HO107-2092 49 1851 Weston Mother-in- Mary Culpin 61 1790 Female Uppingham Rutland England ketton Rutland HO107-2094 84 1851 law Elizabeth Culpin Visitor 30 1821 Female Ketton Rutland England ketton Rutland HO107-2094 84 1851 William Culpin Head 59 1792 Male Ag Lab Ketton Rutland England Clipsham Rutland HO107-2094 8 1851 Mary Culpin Wife 60 1791 Female Carlby Lincs England Clipsham Rutland HO107-2094 8 1851 Thomas Culpin Son 39 1812 Male Ag Lab Clipsham Rutland England Clipsham Rutland HO107-2094 8 1851 Edith Edith William Culpin Head 41 1810 Male Rutland England Rutland HO107-2092 23 1851 Shepherd Weston Weston Colly Edith Elizabeth Culpin Wife 45 1806 Female rthamptonsh England Rutland HO107-2092 23 1851 Weston Weston -

Land at Great Casterton, Stamford, Rutland

A productive parcel of Grade 2 arable land, North of Stamford, in Rutland Land at Great Casterton, Stamford, Rutland Land at Great Casterton Farm Business Tenancy Overage Health & Safety The land is currently let on a Farm Business The property is subject to overage provisions. Given the potential hazards of a working farm we Stamford, Rutland, PE4 4AT Tenancy which is due to terminate on 26 These will apply in the event of a change of ask you to be as vigilant as possible when making September 2018. use of all or part of the land for uses other than your inspection for your own personal safety. A productive parcel of Grade 2 arable agriculture. In such instance, the buyer (and land in an outstanding area of Rutland, Services successors in title) will pay to the seller 50% of Directions North of Stamford There are no services to the property. the uplift in value for a period of 80 years. From Stamford, take the B1081 Casterton Road towards Tickencote. At the crossroads in the Stamford 2 miles, Peterborough 18 miles, Wayleaves, Rights of Way & Easements Local Authority village of Great Casterton take the right hand Melton Mowbray 20 miles The sale is subject to all rights of support, Rutland County Council Tel: 01572 722577 turn onto Ryhall Road, leading towards Ryhall. including public and private rights of way, water, The land is located on the right hand side after Location light, drainage and other easements, quasi- VAT approximately 0.75 miles. The land lies to the North East of Great easements, wayleaves and restrictive covenants Any guide price quoted or discussed is Casterton village in Rutland, the land is accessed and all existing proposed wayleaves for masts, exclusive of VAT. -

Out of Print Click to Download

Number One . .. " .. "'. '\� . .. :,;. :':f..• � .,1- '. , ... .Alt,;'�: ' � .. :: ",' , " • .r1� .: : •.: . .... .' , "" "" "·';'i:\:.'·'�., ' ' • •• ·.1 ..:',.. , ..... ,:.' ::.,::: ; ')"'� ,\:.", . '." � ' ,., d',,,·· '� . ' . � ., ., , , " ,' . ":'�, , " ,I -; .. ',' :... .: . :. , . : . ,',." The Rutland Record Society was formed in May 1979. Its object is to advise the education of the public in the history of the Ancient County of Rutland, in particular by collecting, preserving, printing and publishing historical records relating to that County, making such records accessible for research purposes to anyone following a particular line of historical study, and stimUlating interest generally in the history of that County. PATRON Col. T.C.S. Haywood, O.B.E., J.P. H.M. Lieutenant for the County of Leicestershire with special responsibility for Rutland PRESIDENT G.H. Boyle, Esq., Bisbrooke Hall, Uppingham CHAIRMAN Prince Yuri Galitzine, Quaintree Hall, Braunston, Oakham VICE-CHAIRMAN Miss J. Spencer, The Orchard, Braunston, Oakham HONORARY SECRETARIES B. Matthews, Esq., Colley Hill, Lyddington, Uppingham M.E. Baines, Esq., 14 Main Street, Ridlington, Uppingham HONORAR Y TREASURER The Manager, Midland Bank Limited, 28 High Street, Oakham HONORARY SOLICITOR J.B. Ervin, Esq., McKinnell, Ervin & MitchelI, 1 & 3 New Street, Leicester HONORARY ARCHIVIST G.A. Chinnery, Esq., Pear Tree Cottage, Hungarton, Leicestershire HONORAR Y EDITOR Bryan Waites, Esq., 6 Chater Road, Oakham COUNCIL President, Chairman, Vice-Chairman, Trustees, Secretaries,