Fewj.Pdf (PDF, 7.266Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLANNING APPLICATION REPORT Case Officer: David Cooper Ward: Bridestowe Ward Member: Cllr L J G Hockridge Application

PLANNING APPLICATION REPORT Case Officer: David Cooper Ward: Bridestowe Ward Member: Cllr L J G Hockridge Application No: 01172/2013 Agent/Applicant: Applicant: Mr A Weed Miss P Ogborne Woodbury Farm Fursdon Farm Chilla Bratton Clovelly Beaworthy Okehampton Devon EX20 4JG EX21 5XE Site Address: South Fursdon Farm, Bratton Clovelly, Okehampton, EX20 4JG Development: Replacement dwelling © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 100023302 Scale 1:1250 For internal reference only – no further copies to be made Reason item is being put before Committee Called in by Cllr John Hockridge - Member for Bridestowe Ward “Although the Bungalow is in a bad state of repair. The property does have Mains Electricity and Water. The applicant has paid the Council Tax monthly on the property. I would like this application to go to committee.” Recommendation: Refusal Reasons for Refusal 1. National Planning Policy Framework 2012 Paragraph 55 Requires that to promote sustainable development in rural areas ... “Local planning authorities should avoid new isolated homes in the countryside unless there are special circumstances” This underscores West Devon Borough Council Local Development Framework Core Strategy DPD (2006 – 2026) Strategic Policy 5 defining that housing in the countryside will be strictly controlled and only be permitted where there is clear essential agricultural, horticultural or forestry need can be demonstrated in addition to West Devon Borough Local Plan Review 2005 saved Policy H31 restricting residential development outside the defined limits of settlements. While it is noted that the application is for the replacement of a derelict former dwelling, in applying the common law test to establish whether a dwelling has been abandoned, the former dwelling in this case is reasonably considered to be, as a matter of fact and degree, abandoned. -

(Electoral Changes) Order 1999

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1999 No. 2472 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Torridge (Electoral Changes) Order 1999 Made ---- 6thSeptember 1999 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated January 1999 on its review of the district of Torridge together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Torridge (Electoral Changes) Order 1999. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of all proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— ‘‘the district’’ means the district of Torridge; ‘‘existing’’, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; and any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked ‘‘Map of the District of Tor- ridge (Electoral Changes) Order 1999’’, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c). -

Archaeological Investigation at Hartland, Devon

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION AT HARTLAND, DEVON EXPLORING ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT MARCH 2009 A Report for The Hartland Society ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION AT HARTAND, DEVON By Penny Cunningham PhD With contributions by Stephen Hobbs, David Miller, Tim Robinson, Catherine Griffiths and Henrietta Quinnell March 2009 2 Acknowledgements Thanks are due to Sir Hugh and Lady Stucley for giving permission to conduct geophysical surveys and an evaluation excavation and to the tenant farmers Mr and Mrs Davey. The Warren is also under the Countryside Stewardship Scheme and additional thanks go to Simon Tame of Natural England for giving permission to conduct the evaluation excavation. A big thanks is also due to Stephen and Liz Hobbs for all the help in organising the geophysical surveys, excavation and volunteers. Without their support and enthusiasm none of this work would have been possible. The geophysical survey was undertaken by a number of people and thanks are due to Sean Hawken and David Miller. Thanks are also due to additional geophysical surveying undertaken by David Miller and Tim Robinson (Hartland Abbey). The excavation benefited from the hard work of a large number of people, in particular, Sam Walls, Wendy Howard, and Becky Miller who all worked tirelessly to ensure a high standard was maintained throughout the excavation. Alison Mills from Barnstaple Museum gave advice and support during the excavation and also provided help with the school activities. Thanks also go to Bill Horner and Francis Griffiths for all their sound advice during the planning stage. Jonathan Bray, Simon Hogg, Peter Jones, Dean McMullen, Harry West-Taylor and Fiona Reading helped with the post excavation work, especially with the illustrations. -

Get Around the North Devon Festival With

Bursting with experiences Over 150 events to enjoy Many of them free 3, 2, 1 .. it’s here Thank yo u .. After the long cold winter may only flourish briefly, North Devon Festival to our funders and supporters, without whom the festival would not be possible. the North Devon Festival is so don’t miss them. is produced by Major funder Sponsors Media supporters ready to unfurl its many Choose from over 150 blooms this June. The events North Devon Gazette assorted events including come in all shapes, sizes North Devon Journal Art Trek Open Studios , Community & Heritage and colours, some may Primary Times GoldCoast Oceanfest , Fringe Queen’s Theatre, Boutport thrive the whole month The Voice – Festival FM Theatrefest , Barnstaple Street, Barnstaple, North through, whereas others Fringe , plus music, dance, Devon, EX31 1SY We would also like to comedy, drama, community Other funders Box Office: 01271 32 42 42 extend our thanks to all & heritage, nature and northdevonfestival.org our business supporters. n c e action events, many of Barnstaple Fringe d a which are free. Brochure design by Bruce Aiken Distributed by TMS Marketing It’s all waiting to be Website designed and hosted by NetTecs experienced – so what will studio@QT you do this June? jazz t h e a t r e drama n u f d n w o r s p o k e c o m e d y 2 3 Explore online... where the information is infinite and don’t forget eNews - Stay abreast of the action and sign up today The Voice Listen out for updates on our dedicated festival radio station. -

Application-Form-For

www.mikewye.co.uk 01409 281644 [email protected] Application Form: Warehouse Operative This is a 40 hour per week position requiring physical work and lifting Please complete and return by email to [email protected] or post to: FAO Ryan Stojic Mike Wye & Associates Ltd. Buckland Filleigh Sawmills, Buckland Filleigh, Devon EX21 5RN Personal Information Surname: Forename(s): Title (Mr, Mrs, Miss, etc): Previous names (if any): Address for communications: Daytime telephone number: Email address: Are you subject to immigration control? YES / NO Are you free to take up employment in the UK? YES / NO Buckland Filleigh Sawmills, Buckland Filleigh, Beaworthy, Devon EX21 5RN Tel: 01409 281644 Registered in England & Wales No.6510748 Registered Office: The Custom House, The Strand, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 1EU www.mikewye.co.uk 01409 281644 [email protected] Education From GCSE or equivalent to degree level in chronological order Establishment Qualifications gained Do you have your own transport and a valid driving licence? YES/NO Do you hold any of the following certificates/qualifications?: ⚫ HGV Class 2 YES/NO ⚫ Lorry mounted crane YES/NO ⚫ Forklift YES/NO ⚫ Skid steer loader YES/NO Do you have any other relevant certificates? (Health & Safety, Manual Handling, First Aid etc.) Buckland Filleigh Sawmills, Buckland Filleigh, Beaworthy, Devon EX21 5RN Tel: 01409 281644 Registered in England & Wales No.6510748 Registered Office: The Custom House, The Strand, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 1EU www.mikewye.co.uk 01409 281644 [email protected] Work experience Please give details of your last three jobs. Any relevant posts held before then may also be mentioned. -

Grenville Research

David & Jenny Carter Nimrod Research Docton Court 2 Myrtle Street Appledore Bideford North Devon EX39 1PH www.nimrodresearch.co.uk [email protected] GRENVILLE RESEARCH This report has been produced to accompany the Historical Research and Statement of Significance Reports into Nos. 1 to 5 Bridge Street, Bideford. It should be noted however, that the connection with the GRENVILLE family has at present only been suggested in terms of Nos. 1, 2 and 3 Bridge Street. I am indebted to Andy Powell for locating many of the reference sources referred to below, and in providing valuable historical assistance to progress this research to its conclusions. In the main Statement of Significance Report, the history of the buildings was researched as far as possible in an attempt to assess their Heritage Value, with a view to the owners making a decision on the future of these historic Bideford properties. I hope that this will be of assistance in this respect. David Carter Contents: Executive Summary - - - - - - 2 Who were the GRENVILLE family? - - - - 3 The early GRENVILLEs in Bideford - - - - 12 Buckland Abbey - - - - - - - 17 Biography of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 18 The Birthplace of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 22 1585: Sir Richard GRENVILLE builds a new house at Bideford - 26 Where was GRENVILLE’s house on The Quay? - - - 29 The Overmantle - - - - - - 40 How extensive were the Bridge Street Manor Lands? - - 46 Coat of Arms - - - - - - - 51 The MEREDITH connection - - - - - 53 Conclusions - - - - - - - 58 Appendix Documents - - - - - - 60 Sources and Bibliography - - - - - 143 Wiltshire’s Nimrod Indexes founded in 1969 by Dr Barbara J Carter J.P., Ph.D., B.Sc., F.S.G. -

Littleham & Landcross Parish Council Minutes of The

LITTLEHAM & LANDCROSS PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD AT LITTLEHAM VILLAGE HALL ON THURSDAY 8TH March 2012. Present: Cllrs. Atkinson (Chairman), Corkery, Pat Fishleigh, Hassall, Heard, Hopkins Loraine Kindley and Stevens. DCC Cllr Robinson; TDC Cllr Pennington. Apologies: Cllrs. Beer, Hamilton, Phillips and Smith Members of the public wishing to address the meeting on a specific agenda item, were, in accordance with Standing Order 24 and Paragraph 12(2) of Statutory Instrument 2007/1159, permitted to do so before that Agenda Item. P 1168 - Registration of Members Interests: No additional registrations were required. 1169 - To confirm Minutes 1152-1167 of 19th January 2012. (previously dispatched) Minutes Proposed as correct by Cllr Fishleigh. S: Cllr Heard. All agreed; Minutes signed by Chair. 1170- Matters Arising – Not Covered by Agenda: a) Broadband – Devon & Somerset Funds. Request from Community Council of Devon [CCD] to identify and map the Primary Connection Points [2] for Littleham & Landcross. This was done by Cllrs Beer and Atkinson. b) DCC. Part-night lighting. Response received from Mr D`Alesio – after contact from DCC Cllr Robinson on our behalf. The instruction to the contractor will be issued, and the Council will be advised when work is to take place. It is not expected to happen in the current financial year. Councillors expressed their disappointment that this economy measure has still not been implemented. c) DCC – Buffet lunch. The Chair and Clerk had been invited to attend at County Hall on February 24 th to celebrate the contribution made by Parish Councils to the life of Devon. -

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

Northern Devon in the Domesday Book

NORTHERN DEVON IN THE DOMESDAY BOOK INTRODUCTION The existence of the Domesday Book has been a source of national pride since the first antiquarians started to write about it perhaps four hundred years ago. However, it was not really studied until the late nineteenth century when the legal historian, F W Maitland, showed how one could begin to understand English society at around the time of the Norman Conquest through a close reading and analysis of the Domesday Book (Maitland 1897, 1987). The Victoria County Histories from the early part of the twentieth century took on the task of county-wide analysis, although the series as a whole ran out of momentum long before many counties, Devon included, had been covered. Systematic analysis of the data within the Domesday Book was undertaken by H C Darby of University College London and Cambridge University, assisted by a research team during the 1950s and 1960s. Darby(1953), in a classic paper on the methodology of historical geography, suggested that two great fixed dates for English rural history were 1086, with Domesday Book, and circa 1840, when there was one of the first more comprehensive censuses and the detailed listings of land-use and land ownership in the Tithe Survey of 1836-1846. The anniversary of Domesday Book in 1986 saw a further flurry of research into what Domesday Book really was, what it meant at the time and how it was produced. It might be a slight over-statement but in the early-1980s there was a clear consensus about Domesday Book and its purpose but since then questions have been raised and although signs of a new shared understanding can be again be seen, it seems unlikely that Domesday Book will ever again be taken as self-evident. -

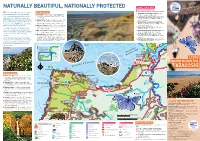

NATURALLY BEAUTIFUL, NATIONALLY PROTECTED O C

l n e Lundy a n h Ilfracombe C l • 349m t o •Hele ▲ s Bull Point Lee •Combe Martin i ▲206m E r • xm oo B r N at Morte Point •Mortehoe io na Lundy l P a Island A399 rk ▲266m Woolacombe• h A3123 ▲337m t A39 a 199m P ▲ Morte Bay t Minehead s Torridge Circular Walksa i NATURALLY BEAUTIFUL, NATIONALLY PROTECTED o C 1 All walks downloadable fromt s Northam Burrowsi https://www.northdevon-aonb.org.uk/exploree W Welcome to the North Devon Coast Areas Torridge Beachesi 9. Westward Ho! A Dynamich Coastline, 5.5km, of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Baggy Point t • Mouthmill – Rocky. Access through woods from Moderate. Start: on pebbleu ridge. o This is nationally designated to conserve Coast path – 2km from Brownsham (NT) or 3km S 10. Abbotsham and Westward Ho! Cultural Trail, 2 from Clovelly. and enhance the 171 km of distinctive 9km, Easy to Moderate. Start:•Georgeham Seafield car and dramatic coastal landscapes of North • Peppercombe – Pebbles/shingle with sand at low park, Westward•Croyde Ho! Devon and Torridge. Braunton Burrows at tide. Access via Footpath through valley. Nearest Croyde11. Bay Westward Ho!, Seafield and Cornborough the centre of the AONB, is the core of the parking 3km in roadside layby near Horns Cross. Easy Access Trail, 1.4km, Easy. Start: Seafield North Devon UNESCO Biosphere. • Spekes Mill Mouth – Pebbles with sand at low tide. car park, Westward Ho!Saunton 1.4km walk from Hartland Quay along Coast path. 12. Bucks Mills Cultural Trail • , 9km, Moderate. The landscape varies from wild coastal Access via steep steps. -

Holsworthy Market Report

HOLSWORTHY MARKET REPORT Wednesday 26 August 2020 EVERY WEDNESDAY Gates open 6am SALE TIMES 09:45 am - Draft Ewes followed by Finished Lambs 10:30 am - Store Lambs 09.45 am - Calves and Stirks 11:00 am - Store Cattle followed by Finished & OTM Cattle 11:00 am - Dairy Cattle Another sensational day at Holsworthy comes to an end with just under 400 Beef cattle, 200 Dairy cattle, 230 Calves and 1200 Sheep with a top call of £2000 on behalf of Messrs S R Gilbert & Son. Holsworthy Livestock Market, New Market Road, Holsworthy, Devon, EX22 7FA 01409 253275 748 LAMBS, 399 DRAFT EWES & RAMS WEIGHT TOP AVERAGE Per P/Kg Per P/Kg 09.45 am LAMBS head TLW head TLW Auctioneer: Steve Prouse 07767 895366 39.1-45.5 99.50 228 90 209.5 748 LAMBS The lamb trade has rallied around again up around £4 per 45.6-52 102.50 220 97 205.4 head, our overall average on the day 209.5, well up on other Overall 102.50 228 93.10 209.5 centres earlier in the week. Several pens over 220p to a top EWES of 228p for a smart pen of 43kg £98 from Mr & Mrs Tucker Light 84 70 of Hatherleigh followed by Robert Lee of Winscott, Bideford who realized 226p for his 44kg £99.50. Numerous Heavy 103.5 92 pens over £98 to a top of £102.50 for a pen of 46kg from Rams 100 86 Graham Cowling of Bude. 231 STORE LAMBS As previous weeks all store lambs very much sought after. -

Historical Notes Relating to Bideford's East-The-Water Shore.Odt

Historical Notes relating to Bideford's East-the-Water Shore A collection, in time-line form, of information pertaining primarily to the East-the-Water shore. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................13 Nature of this document.............................................................................................................13 Development of this document...................................................................................................13 Prior to written records...................................................................................................................13 Prehistory...................................................................................................................................13 Stone Age, flint tools and Eastridge enclosure............................................................................14 Roman period, tin roads, transit camps, and the ford..................................................................15 A Roman transit camp between two crossings.......................................................................15 An ancient tin route?.............................................................................................................15 The old ford...........................................................................................................................15 Saxon period, fisheries (monks and forts?).................................................................................15