Toccata Classics TOCC 0066 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA a JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Cristian Măcelaru, Conductor

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA A JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Cristian Măcelaru, conductor October 27 and 29, 2017 GEORGES BIZET Suite No. 1 from Carmen (Arr. Fritz Hoffmann) Prelude and Aragonaise Intermezzo Seguedille Les Dragons d’Alcala Les Toréadors WYNTON MARSALIS Violin Concerto in D Major Rhapsody Rondo Burlesque Blues Hootenanny Nicola Benedetti, violin INTERMISSION NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Scheherazade, Op. 35 The Sea and Sindbad’s Ship The Tale of Prince Kalendar The Young Prince and the Princess The Festival at Bagdad; The Sea; The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Suite No. 1 from Carmen GEORGES BIZET Born October 25, 1838, Paris Died June 3, 1875, Bougival Carmen – Bizet’s opera of passion, jealousy and murder – was a failure at its first performance in Paris in March 1875. The audience seemed outraged at the idea of a loose woman and murder onstage at the Opéra-Comique. Bizet died three months later at age 37, never knowing that he had written what would become one of the most popular operas ever composed. After Bizet’s death, his publisher Choudens felt that the music of the opera was too good to lose, so he commissioned the French composer Ernest Guiraud to arrange excerpts from Carmen into two orchestral suites of six movements each. The music from Carmen has everything going for it – excitement, color and (best of all) instantly recognizable tunes. From today’s vantage point, it seems impossible that this opera could have been anything but a smash success from the first instant. The Suite No. 1 from Carmen contains some of the most famous music from the opera, and it also offers some wonderful writing for solo woodwinds. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

É M I L I E Livret D’Amin Maalouf

KAIJA SAARIAHO É M I L I E Livret d’Amin Maalouf Opéra en neuf scènes 2010 OPERA de LYON LIVRET 5 Fiche technique 7 L’argument 10 Le(s) personnage(s) 16 ÉMILIE CAHIER de LECTURES Voltaire 37 Épitaphe pour Émilie du Châtelet Kaija Saariaho 38 Émilie pour Karita Émilie du Châtelet 43 Les grandes machines du bonheur Serge Lamothe 48 Feu, lumière, couleurs, les intuitions d’Émilie 51 Les derniers mois de la dame des Lumières Émilie du Châtelet 59 Mon malheureux secret 60 Je suis bien indignée de vous aimer autant 61 Voltaire Correspondance CARNET de NOTES Kaija Saariaho 66 Repères biographiques 69 Discographie, Vidéographie, Internet Madame du Châtelet 72 Notice bibliographique Amin Maalouf 73 Repères biographiques 74 Notice bibliographique Illustration. Planches de l’Encyclopédie de Diderot et D’Alembert, Paris, 1751-1772 Gravures du Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux & les arts méchaniques, volumes V & XII LIVRET Le livret est écrit par l’écrivain et romancier Amin Maalouf. Il s’inspire de la vie et des travaux d’Émilie du Châtelet. Émilie est le quatrième livret composé par Amin Maalouf pour et avec Kaija Saariaho, après L’Amour de loin, Adriana Mater 5 et La Passion de Simone. PARTITION Kaija Saariaho commence l’écriture de la partition orches- trale en septembre 2008 et la termine le 19 mai 2009. L’œuvre a été composée à Paris et à Courtempierre (Loiret). Émilie est une commande de l’Opéra national de Lyon, du Barbican Centre de Londres et de la Fondation Gulbenkian. Elle est publiée par Chester Music Ltd. -

Kaija Saariaho

Kaija Saariaho TRIOSDANN • FREUND • HAKKILA • HELASVUO JODELET • KARTTUNEN • KOVACIC 1 KAIJA SAARIAHO (1952) 1 Mirage (2007; chamber version) for soprano, cello and piano 15’17 Pia Freund, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila Cloud Trio (2009) for violin, viola and cello 16’12 2 I. Calmo, meditato 3’01 3 II. Sempre dolce, ma energico, sempre a tempo 3’46 4 III. Sempre energico 2’34 5 IV. Tranquillo ma sempre molto espressivo 6’50 Zebra Trio: Ernst Kovacic, Steven Dann, Anssi Karttunen 6 Cendres (1998) for alto flute, cello and piano 9’57 Mika Helasvuo, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila Je sens un deuxième coeur (2003) for viola, cello and piano 19’07 7 I. Je dévoile ma peau 4’21 8 II. Ouvre-moi, vite! 2’16 9 III. Dans le rêve, elle l’attendait 4’10 10 IV. Il faut que j’entre 2’34 11 V. Je sens un deuxième coeur qui bat tout près du mien 5’45 Steven Dann, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila 2 Serenatas (2008) for percussion, cello and piano 16’03 12 Delicato 2’49 13 Agitato 3’13 14 Dolce 1’22 15 Languido 5’41 16 Misterioso 2’56 Florent Jodelet, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila STEVEN DANN, viola PIA FREUND, soprano TUIJA HAKKILA, piano MIKAEL HELASVUO, alto flute FLORENT JODELET, percussion ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello ERNST KOVACIC, violin 3 n the programme note for her string trio piece Cloud Trio, Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952) discusses how Ishe came about the title of the work, recalling her impressions of the French Alps and the cloud formations drifting over the mountains. -

Magnus Lindberg Al Largo • Cello Concerto No

MAGNUS LINDBERG AL LARGO • CELLO CONCERTO NO. 2 • ERA ANSSI KARTTUNEN FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) 1 Al largo (2009–10) 24:53 Cello Concerto No. 2 (2013) 20:58 2 I 9:50 3 II 6:09 4 III 4:59 5 Era (2012) 20:19 ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello (2–4) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor 2 MAGNUS LINDBERG 3 “Though my creative personality and early works were formed from the music of Zimmermann and Xenakis, and a certain anarchy related to rock music of that period, I eventually realised that everything goes back to the foundations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – how could music ever have taken another road? I see my music now as a synthesis of these elements, combined with what I learned from Grisey and the spectralists, and I detect from Kraft to my latest pieces the same underlying tastes and sense of drama.” – Magnus Lindberg The shift in musical thinking that Magnus Lindberg thus described in December 2012, a few weeks before the premiere of Era, was utter and profound. Lindberg’s composer profile has evolved from his early edgy modernism, “carved in stone” to use his own words, to the softer and more sonorous idiom that he has embraced recently, suggesting a spiritual kinship with late Romanticism and the great masters of the early 20th century. On the other hand, in the same comment Lindberg also mentioned features that have remained constant in his music, including his penchant for drama going back to the early defiantly modernistKraft (1985). -

On Teaching the History of Nineteenth-Century Music

On Teaching the History of Nineteenth-Century Music Walter Frisch This essay is adapted from the author’s “Reflections on Teaching Nineteenth- Century Music,” in The Norton Guide to Teaching Music History, ed. C. Matthew Balensuela (New York: W. W Norton, 2019). The late author Ursula K. Le Guin once told an interviewer, “Don’t shove me into your pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over. My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions” (Wray 2018). If it could speak, nineteenth-century music might say the same ornery thing. We should listen—and resist forcing its composers, institutions, or works into rigid categories. At the same time, we have a responsibility to bring some order to what might seem an unmanageable segment of music history. For many instructors and students, all bets are off when it comes to the nineteenth century. There is no longer a clear consistency of musical “style.” Traditional generic boundaries get blurred, or sometimes erased. Berlioz calls his Roméo et Juliette a “dramatic symphony”; Chopin writes a Polonaise-Fantaisie. Smaller forms that had been marginal in earlier periods are elevated to unprecedented levels of sophistication by Schubert (lieder), Schumann (character pieces), and Liszt (etudes). Heightened national identity in many regions of the European continent resulted in musical characteristics which become more identifiable than any pan- geographic style in works by composers like Musorgsky or Smetana. At the college level, music of the nineteenth century is taught as part of music history surveys, music appreciation courses, or (more rarely these days) as a stand-alone course. -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0024 Notes

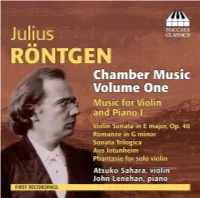

P JULIUS RÖNTGEN, CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME ONE – WORKS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO I by Malcolm MacDonald Considering his prominence in the development of Dutch concert music, and that he was considered by many of his most distinguished contemporaries to possess a compositional talent bordering on genius, the neglect that enveloped the huge output of Julius Röntgen for nearly seventy years after his death seems well-nigh inexplicable, or explicable only to the kind of aesthetic view that had heard of him as stylistically conservative, and equated conservatism as uninteresting and therefore not worth investigating. The recent revival of interest in his works has revealed a much more complex picture, which may be further filled in by the contents of the present CD. A distant relative of the physicist Conrad Röntgen,1 the discoverer of X-rays, Röntgen was born in 1855 into a highly musical family in Leipzig, a city with a musical tradition that stretched back to J. S. Bach himself in the first half of the eighteenth century, and that had been a byword for musical excellence and eminence, both in performance and training, since Mendelssohn’s directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Conservatoire in the 1830s and ’40s. Röntgen’s violinist father Engelbert, originally from Deventer in the Netherlands, was a member of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and its concert-master from 1873. Julius’ German mother was the pianist Pauline Klengel, sister of the composer Julius Klengel (father of the cellist-composer of the same name), who became his nephew’s principal tutor; the whole family belonged to the circle around the composer and conductor Heinrich von Herzogenberg and his wife Elisabet, whose twin passions were the revival of works by Bach and the music of their close friend Johannes Brahms. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century,