Legally "Strong" Shareholders of Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

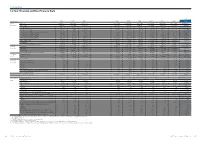

Corporate Data 10-Year Financial and Non-Financial Data

Corporate Data 10-Year Financial and Non-Financial Data (Millions of yen) (Fiscal year) 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 For the Net sales ¥1,858,574 ¥1,864,691 ¥1,685,529 ¥1,824,698 ¥1,886,894 ¥1,822,805 ¥1,695,864 ¥1,881,158 ¥1,971,869 ¥1,869,835 fiscal year Cost of sales 1,570,779 1,635,862 1,510,511 1,537,249 1,581,527 1,548,384 1,465,577 1,595,229 1,704,972 1,638,738 Operating income 124,550 60,555 11,234 114,548 119,460 68,445 9,749 88,913 48,282 9,863 Ordinary income (loss) 89,082 33,780 (18,146) 85,044 101,688 28,927 (19,103) 71,149 34,629 (8,079) Net income (loss) attributable to owners of the parent 52,939 (14,248) (26,976) 70,191 86,549 (21,556) (23,045) 63,188 35,940 (68,008) Cash flows from operating activities 177,795 39,486 45,401 194,294 153,078 97,933 141,716 190,832 67,136 27,040 Cash flows from investing activities (96,686) (85,267) (123,513) (62,105) (73,674) (104,618) (137,833) (161,598) (28,603) (218,986) Cash flows from financing activities (98,196) (40,233) 127,644 (138,501) (156,027) 93,883 16,545 (66,598) (9,561) 140,589 Capital expenditures 91,378 96,085 114,935 101,402 103,522 109,941 160,297 128,653 133,471 239,816 Depreciation 114,819 118,037 106,725 82,936 89,881 94,812 96,281 102,032 102,589 105,346 Research and development expenses 29,832 31,436 30,763 28,494 29,920 29,843 30,102 32,014 34,495 35,890 At fiscal Total assets 2,231,532 2,159,512 2,226,996 2,288,636 2,300,241 2,261,134 2,310,435 2,352,114 2,384,973 2,411,191 year-end Net assets 597,367 571,258 569,922 734,679 851,785 745,492 -

Corporate Governance Models: the Japanese Experience in Context

DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal Volume 15 Issue 1 Fall 2016 Article 2 Corporate Governance Models: the Japanese Experience in Context Maria Lucia Passador Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/bclj Recommended Citation 15 DePaul Bus. & Com. L.J. 25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\D\DPB\15-1\DPB102.txt unknown Seq: 1 1-MAY-17 15:21 Corporate Governance Models: the Japanese Experience in Context Maria Lucia Passador* Avoid the crowd. Do your own thinking independently. Be the chess player, not the chess piece. —Ralph Charell INTRODUCTION: JAPANESE CORPORATE LAW AND ITS REFORM This Article aims to assess the claim that three countries – Italy, Japan and Portugal – present a tripartite,1 Latin, classic,2 and hybrid,3 model of corporate governance. In general, Japanese law seems an “exotic variation of Roman-Ger- manic models,” affected by United States legal models transplanted after World War II, while at the same time, presenting original fea- tures related to the history, evolution, and economic and social legacy of both Buddhist and Confucian philosophies.4 * PhD Candidate in Legal Studies - Business and Social Law, Bocconi University Law School, Milan, Italy; Visiting Researcher, Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA, U.S.A. I am grateful to prof. Piergaetano Marchetti for his valuable, constant guidance and advice, and to prof. -

Share Buyback Rules Under Japanese Corporate Law and Shareholders’ Return

Share Buyback Rules under Japanese Corporate Law and Shareholders’ Return Goya Kobayashi / Takayuki Irome * I. Introduction II. Development of Share Buyback Rules under Japanese Corporate Law 1. History of the deregulation of buyback rules under Japanese corporate law 2. Main reasons for the principle of the prohibition before 2001 3. Background of the change in buyback rules in 2001 4. Reasons for the change in share buyback rules 5. Measures to prevent negative effects of share buybacks 6. Present rules III. Investors’ and Corporations’ Reaction to Share Buyback Today 1. General recognition of share buyback from the side of investors and corporations 2. Commitments on share buybacks made to the market IV. Conclusion I. INTRODUCTION This paper deals with the development of rules regulating a corporation’s repurchase of its own shares (hereinafter ‘share buyback’) under Japanese corporate law and analyses recent changes in the attitudes of management and shareholders towards share buybacks. It is interesting to observe that share buyback is recognised today as a popular tool of shareholder return, whereas the deregulation of share buyback rules in the 1990s and early 2000s was originally intended to give management a countermeasure against hostile takeovers under the market situation of stock price decline. This paper will give an overview of the following points: (1) a history of the deve- lopment of share buyback rules under Japanese company law; (2) the present rules on share buybacks; and (3) corporations’ and shareholders’ reaction to share buybacks after the deregulation of buyback rules, especially after the deregulation of treasury shares in 2001. * Goya Kobayashi is a Fellow Researcher of the Policy Research Institute of the Ministry of Finance, Japan. -

Articles of Incorporation

Revised June 22, 2018 Articles of Incorporation 1 Articles of Incorporation Chapter 1, General Provisions (Company Name) Article 1. The Company will be called Kabushiki Gaisha SUBARU, and in English, SUBARU CORPORATION. (Location of Head Office) Article 2. The Company will establish its head office in Shibuya-ku, Tokyo. (Purpose) Article 3. The purpose of the Company shall be to engage in the following business activities: 1. Manufacture, sales, repair, and lease of the following products, and components and materials related thereto: (1) Automobiles, railway vehicles, industrial vehicles and other vehicles; (2) Airplanes, aerospace related machinery, flying objects, military arms; (3) Engines, engine-equipped machinery, agricultural machinery, forestry machinery, construction machinery, machine tools, pressing machinery, heating and air conditioning equipment, equipment for environment and/or sanitation control, and other industrial and/or general machines and tools; and (4) Telecommunications equipment, measuring equipment, and other electric equipment. 2. Consulting, engineering, and development and sales of any other technology, related to the preceding paragraph. 3. Design, operation, supervision and hire of construction and manufacture, sales and repair of buildings, structures and materials related thereto. 4. Sales, lease, agency and maintenance of real estate. 5. Managing airports. 6. Information processing, information transmission, information providing, and development, sales and lease of software. 7. Transport by land, sea or air, storage, and other transportation services related thereto. 8. Securities investment, securities trading and financing. 9. Dispatch transactions. 10. Security and disaster prevention. 2 11. Advertising agency, travel agency, publishing and printing. 12. Management of facilities with regard to education, medical treatment, sports, tourism, exhibition, entertainment, and other facilities such as restaurants, lodgings and stores. -

![Regulation on Simplified and Foreign Companies in Japan [Article]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1315/regulation-on-simplified-and-foreign-companies-in-japan-article-2061315.webp)

Regulation on Simplified and Foreign Companies in Japan [Article]

Regulation on Simplified and Foreign Companies in Japan [Article] Item Type Article; text Authors Fujita, Tomotaka Citation 33 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. L. 93 (2016) Publisher The University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law (Tucson, AZ) Journal Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law Rights Copyright © The Author(s) Download date 02/10/2021 12:35:33 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/658842 REGULATION ON SIMPLIFIED AND FOREIGN COMPANIES IN JAPAN Tomotaka Fujita TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR OD U CTIO N ............................................................................................... 93 II. REGULATION OF MICRO-, SMALL-, AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES UNDER JA PA N ESE L AW ................................................................................................... 94 A . T he B ackground ....................................................................................... 94 B . O rganizational Structure ........................................................................... 97 C. Lim ited Liability of the M em bers ............................................................ 98 D. Flexibility and Contractual Freedom ...................................................... 99 E. Incorporation Requirements (Including Minimum Capital and Purpose R equ irem en ts) ............................................................................................... 99 F. Fiscal Transparency and Simplified Accounting -

2015 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said table of contents 6 - Board of Directors and Key Executive Officers 7 - Board of Directors’ Report 9 - Profile of the Major Shareholders 12 - Corporate Social Responsibility 13 - Management Discussion and Analysis Report 22 - Corporate Governance Report. 33 - Audited Financial Statements 6 AL BATINAH POWER | Annual Report 2015 BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND KEY EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Board of Directors Representing Mrs. Catherine Lorgere Chouteau Chairperson Kahrabel Mr. Padmanabhan Ananthan Deputy Chairman Multitech Mr. Ajeet A. Walavalkar Director Mr. David Joseph Orford Director Mr. Guillaume Baudet Director Mr. Hachiman Yokoi Director BHSP Mr. Hadi Said Humaid Al-Harthy Director PASI Mr. Mohamed Amur Mohamed Al-Mamari Director CSEPF Mr. Mohammad Ribhi Izzat AlHusseini Director MODPF Mr. Peter Shaw Director Mr. Takahito Iima Director SEPI Key Executive Officers Mr. Jurgen De Vyt Chief Executive Officer Mr. So Murakami Chief Financial Officer AL BATINAH POWER | Annual Report 2015 7 BOARD OF DIRECTORSÕ REPORT Dear Shareholders, On behalf of the Board of Directors of Al Batinah Power Company SAOG (the “Company”), I have the pleasure to present the Annual Report of the Company for the year ended 31 December 2015. Corporate Governance During the year, the Company extensively reviewed internal policies and procedures in order to ensure highest standards of corporate governance in compliance with local regulatory requirements as well as with international standards and industry best practices. This exercise led to revision of existing as well as development of certain additional policies and procedures. The Company expects this exercise to enhance the internal controls within the Company. -

Lion Corporation Basic Corporate Governance Policy

Lion Corporation Basic Corporate Governance Policy Section 1. General Rules 1. Purpose (2.1, 3.1.i) Based on its corporate motto and management philosophy, Lion Corporation (“Lion,” “the Company”) has established this Basic Corporate Governance Policy (“the Basic Policy”) to enhance the corporate value of the Company and its affiliated companies (collectively the “Lion Group”). Company Motto Lion Corporation positions “Fulfilling a Spirit of Love” as fundamental to its management, and thus contributes to the enrichment of the happiness and lives of people. Management Philosophy 1. We bring together the power of our personnel, the power of our technology and the power of our marketing as we provide superior products that are helpful in the daily lives of people. 2. We respect the "Spirit of Tenacity and Creativity" that we have maintained since our founding as we continue developing our business. 3. We deeply appreciate all those who extend their valuable support to us as we prosper together through sincerity and mutual trust. 2. Basic Approach to Corporate Governance (3.1.ii) Lion’s top priorities for corporate governance are to increase management transparency, strengthen supervisory functions, accelerate decision making and ensure compliance. By strengthening and enhancing its corporate governance systems, Lion aims to increase its corporate value. 3. Establishment and Abolishment of the Basic Policy The Basic Policy is established, and may be abolished, by resolution of the Board of Directors. Established June 30, 2016 Amended February 9, 2018 Amended October 31, 2018 Amended February 12, 2021 The numbers in parentheses at the start of each section of this Basic Policy indicate the related sections of Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc.’s Corporate Governance Code. -

Investigation Report

TRANSLATION FOR REFERENCE PURPOSSE ONLY Investigation Report January 7, 2012 Olympus Corporation Director Liability Investigation Committee TRANSLATION FOR REFERENCE PURPOSSE ONLY January 7, 2012 To the Board of Auditors of Olympus Corporation Olympus Corporation Director Liability Investigation Committee Chairman Commissioner Kazuo Tezuka [seal:] Kazuo Tezuka Commissioner Hideki Matsui [seal:] Attorney Hideki Matsui Commissioner Satoru Mitsumori [seal:] Attorney Satoru Mitsumori TRANSLATION FOR REFERENCE PURPOSSE ONLY List of Abbreviations and Terms Abbreviation/Term Official name and explanation EXEMPTED LIMITED PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT between Olympus/ GCI Cayman that sets forth such items as the transfer of 30 billion yen (said amount is Agreement Dated March 1, 2000 revised accordingly) to QP at the request of Olympus for the purpose of short-term money management The 2009 Committee’s Report A report dated May 17, 2009 by 3 outside experts that includes attorneys Twenty First Century Global Fixed Income Fund Ltd. A Pass-Through Fund of Cayman registry that was involved in the Singapore Route. The Director is Mori. Money was transferred to 21C in the form of Hillmore and Easterside having made loans, etc., and money was transferred in the amounts of 20 billion yen to 21C Proper and 19.3 billion yen to CFC respectively in the form of 21C subscribing for bonds issued by Proper and CFC. Note that out of the 20 billion yen that was transferred to Proper, 8 billion yen was transferred to CFC by means of Proper subscribing for bonds issued by CFC. Axam Investments Ltd. A Cayman company formed on November 19, 2007 by Sagawa in order to receive the money that was to be paid by Olympus accompanying the Gyrus acquisition as part of AXAM the Loss Separation Settlement Scheme. -

To Create a Vibrant Environment for All Members of Society

To Create a Vibrant Environment for All Members of Society The Taisei Group creates “safe, secure, and attractive spaces” and “high value” in harmony with the nature, and strives to build a global society filled with dreams and hopes for the next generation. Taisei Group Philosophy Taisei Spirit To Create a Vibrant Environment for Taisei Group Active and Transparent Culture / All Members of Society Philosophy Value Creation / Evolution of Tradition Objectives to be Pursued by the Taisei Group (Goals) Key Concepts That All Taisei Group Officers and Employees Must Adhere to in Order to Pursue and Realize the Taisei Group Philosophy Taisei Spirit Action Guidelines for Taisei Personnel and the Taisei Group as a Whole Overall Overall Medium-term Business Plan Principles of Management (FY2018 – FY2020) Conduct Perspective Individual Policies Customers Shareholders / Investors Suppliers Employees Local Communities In order to pursue the Taisei Group Philosophy “To Create a Vibrant Environment for All Members of Society,” all officers and employees share the “Taisei Spirit,” and carry out corporate actions based on the Group Action Guidelines and Individual Policies “Overall Principles of Conduct” and “Overall Management Perspective” and Medium-term Business Plan. The aim is to create new social value in the course of these actions through the wishes and expectations of our stakeholders, while being aware of the issues of sustainable society and contributing towards their resolution. 1 TAISEI ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Group Slogan* * The Taisei Group Philosophy, the Taisei Spirit and the Action Guidelines for Taisei Personnel and the Taisei Group as a Whole can be summed up in the following slogan. -

Corporate Governance 2018 11Th Edition a Practical Cross-Border Insight Into Corporate Governance

ICLGThe International Comparative Legal Guide to: Corporate Governance 2018 11th Edition A practical cross-border insight into corporate governance Published by Global Legal Group, with contributions from: Advokatfirman Lindahl Miyetti Law Aksac Law Office Montel&Manciet Advocats Arnold Bloch Leibler Nielsen Nørager Law Firm LLP Ashurst Hong Kong Nishimura & Asahi Astrea Novotny Advogados Borenius Attorneys Ltd Ritch, Mueller, Heather y Nicolau, S.C. bpv Hügel Rechtsanwälte GmbH Slaughter and May Čechová & Partners SZA Schilling, Zutt & Anschütz Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH CR Partners Szarvas and Partners Law Firm Ferraiuoli LLC Taylors in association with Walkers Genesis Law Corporation Tian Yuan Law Firm Georgiev, Todorov & Co. Trevisan & Associati Glatzová & Co. Trilegal GRATA International UGGC Law Firm Guevara & Gutiérrez S.C. Villey Girard Grolleaud Houthoff Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Lee & Ko Walalangi & Partners in association with Nishimura & Asahi Lenz & Staehelin WBW Weremczuk Bobeł & Partners Attorneys at Law McCann FitzGerald WH Partners The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Corporate Governance 2018 General Chapter: 1 Corporate Governance, Investor Stewardship and Engagement – Sabastian V. Niles, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz 1 Country Question and Answer Chapters: Contributing Editor Sabastian V. Niles, Wachtell, 2 Albania CR Partners: Anisa Rrumbullaku & Tea Take 6 Lipton, Rosen & Katz Sales Director 3 Andorra Montel&Manciet Advocats: Maïtena Manciet Fouchier & Florjan Osmani Liliana Ranaldi González 12 Account -

Mgt Economic Development Institute

\. G 2 Aq2 *mgt Economic Development Institute of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Cleaning Up the Balance Sheets Japanese Experience in the Postwar Reconstruction Period Public Disclosure Authorized Takeo Hoshi Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized EDI WORKING PAPERS * Number 94-51 STUDIES AND TRAINING DESIGN DIVISION EDI Working Papers are intended to provide an informal means for the preliminary dissemination of ideas with the World Bank and among EDI's partner institutions and others interested in development issues. Thebacklistof EDI training materials and publications is shown in theannual CatalogofTraining Materials which is available from:. Training Materials Resources Center, Room M-P1-010 Economic Development Institute The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433, USA Telephone: (202) 473-6351 Facsimile: (202) 676-1184 Cleaning Up the Balance Sheets Japanese Experience in the Postwar Reconstruction Period Takeo Hoshi The Economic Development Institute of The World Bank Copyright @ 1994 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. The World Bank enjoys copyright under protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. This material may nonetheless be copied for research, educational, or scholarly purposes only in the member countries of The World Bank. Material in this series is subject to revision. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this document are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or the members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. -

Regulation on Simplified and Foreign Companies in Japan

REGULATION ON SIMPLIFIED AND FOREIGN COMPANIES IN JAPAN Tomotaka Fujita* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 93 II. REGULATION OF MICRO-, SMALL-, AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES UNDER JAPANESE LAW ....................................................................................................... 94 A. The Background ........................................................................................... 94 B. Organizational Structure ............................................................................... 97 C. Limited Liability of the Members ................................................................ 98 D. Flexibility and Contractual Freedom ........................................................... 99 E. Incorporation Requirements (Including Minimum Capital and Purpose Requirements) ................................................................................................... 99 F. Fiscal Transparency and Simplified Accounting ........................................ 101 III. REGULATION OF FOREIGN COMPANIES IN JAPAN ........................................... 102 A. Recognition of Foreign Companies and Applicable Law .......................... 102 B. Requirements for Foreign Companies Carrying out Transactions Continuously in Japan ..................................................................................... 103 C. Pseudo-Foreign Companies .......................................................................