Chapter 2. Colombo Under Dutch Rule (1656 - 1796)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka November 2017 Dimantha De Silva, Ph.D(Calgary), P.Eng.(Alberta) Senior Lecturer, University of Moratuwa 1 SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Table of Content Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background and Purpose .............................................................................................................. 4 Study Area .................................................................................................................................... 5 Existing Transport Master Plans .................................................................................................. 6 Indicator 1: Extent to which Transport Plans Cover Public Transport, Intermodal Facilities and Infrastructure for Active Modes ............................................................................................... 7 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 8 Indicator 2: Modal Share of Active and Public Transport in Commuting................................. 13 Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

Dress Fashions of Royalty Kotte Kingdom of Sri Lanka

DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA . DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. Dedication First Edition : 2017 For Vidyajothi Emeritus Professor Nimal De Silva DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KingDOM OF SRI LANKA Eminent scholar and ideal Guru © Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne ISBN 978-955-30- Cover Design by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd Page setting by: Nisha Weerasuriya Published by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. 661/665/675, P. de S. Kularatne Mawatha, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka. Printed by: Chathura Printers 69, Kumaradasa Place, Wellampitiya, Sri Lanka. Foreword This collection of writings provides an intensive reading of dress fashions of royalty which intensified Portuguese political power over the Kingdom of Kotte. The royalties were at the top in the social strata eventually known to be the fashion creators of society. Their engagement in creating and practicing dress fashion prevailed from time immemorial. The author builds a sound dialogue within six chapters’ covering most areas of dress fashion by incorporating valid recorded historical data, variety of recorded visual formats cross checking each other, clarifying how the period signifies a turning point in the fashion history of Sri Lanka culminating with emerging novel dress features. This scholarly work is very much vital for university academia and fellow researches in the stream of Humanities and Social Sciences interested in historical dress fashions and usage of jewelry. Furthermore, the content leads the reader into a new perspective on the subject through a sound dialogue which has been narrated through validated recorded historical data, recorded historical visual information, and logical analysis with reference to scholars of the subject area. -

Battle of the “Species” to Play the Role of “National Bourgeoisie”: a Reading of Shyam Selvadurai's Cinnamon Gardens A

9ROXPH,,,,VVXH9-XO\,661 Battle of the “Species” to play the Role of “National bourgeoisie”: A Reading of Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy Niku Chetia Gauhati University India Decolonization is quite simply the replacing of a certain “species” of men by another “species” of men. (Fanon, 1963) Fanon had quite rightly pointed out in his work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961) that during the colonial and post-colonial period, the battle for dominating, suppressing and subjugating certain groups of people by a superior class never ceases to exist. He explains that there are two species- “Colonisers” and “National bourgeoisie” of the colonised- who seeks to rule the country after independence. Though he places his ideas in an African context, his arguments seems valid even for a South-East Asian country like Sri Lanka. After colonisers left the nation, there emerged a pertinent question - Who would play the role of national bourgeoisie? The struggle to play the coveted role drives Sri Lanka through ethnic conflicts and prejudices among them. The two dominant “species” battling for the position are: Tamils and Sinhalese. Considering the Marxist model of society, Althusser in work On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses claims that the social structure is composed of Base and Superstructure. The productive forces (labour forces/working class) and relations of production forms the Base while religious ideology, ethics, politics, family, identity and politico-legal (law and state) forms the superstructure (237). The National bourgeoisie exists in the superstructure. Both the groups try to survive in the superstructure.The objective of this paper is to study Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy and excavate the diverse ways in which these two mammoth ethnic groups struggle to oust one another and form the “national bourgeoisie”. -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

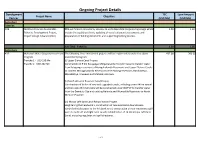

Ongoing Project Details

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

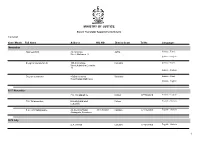

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Part I: the Kandyan Kings and Cosmopolitan Discourse

THE MANY FACES OF THE KANDYAN KINGDOM, 1591-1765: LESSONS FOR OUR TIME?1 PART I: THE KANDYAN KINGS AND COSMOPOLITAN DISCOURSE Introduction This paper discusses the reign of Vimaladharmasūriya, the first consecrated king of Kandy (1591-1604) and his successors during whose reigns the Kandyan kingdom became a place that provided a home for diverse cultures and communities. Prior to this Kandy was ruled by three local kings, the first being Senāsammata Vikramabāhu (c. 1469-1511). Senāsammata means elected by the sēna or army or perhaps by members of the aristocratic class known as banḍ āras (“lords).” Vikramabāhu tried to assert his independence from the sovereign kings of Kōṭṭe. That kingdom commenced with Bhūvanekabāhu V (1371-1408) and ended with Bhūvanekabāhu VII (1521-51) and his grandson Dharmapāla (1551- 1597), the first Catholic sovereign. Vikramabāhu was badly defeated and had to pay a large tribute. After Dharmapāla died Kōṭṭe became part of Portugal which now had control over much of Jaffna in the north and the Maritime provinces in the south. The Portuguese were a presence in Kōṭṭe from 1506 and had the support of Bhūvanekabāhu VII but not his brother Māyādunne, the ruler of Sītāvaka 1 who was a foe of the Portuguese. His intrepid son Rājasinha I (1581-1593) at one time nearly brought about the whole kingdom of Kōṭṭe and much of Kandy under his rule. As for the fortunes of Kandy Vikramabāhu was followed by his son Jayavīra Banḍ āra (1511- 1552) during whose time Catholic friars became a presence in the court.2 In order to please the Portuguese and the king of Kōṭṭe he became a nominal Catholic until he was deposed and exiled by his son Karalliyadde Banḍ āra (1552-1582) who became a devoted Catholic and publicly embraced Catholicism around 1562-1564. -

* Omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1

* omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1 dutch ships in tropical waters robert parthesius The end of the 16th century saw Dutch expansion in Asia, as the Dutch East India Company (the VOC) was fast becoming an Asian power, both political and economic. By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen. This landmark study looks at perhaps the most important tool in the Company’ trading – its ships. In order to reconstruct the complete shipping activities of the VOC, the author created a unique database of the ships’ movements, including frigates and other, hitherto ignored, smaller vessels. Parthesius’s research into the routes and the types of ships in the service of the VOC proves that it was precisely the wide range of types and sizes of vessels that gave the Company the ability to sail – and continue its profitable trade – the year round. Furthermore, it appears that the VOC commanded at least twice the number of ships than earlier historians have ascertained. Combining the best of maritime and social history, this book will change our understanding of the commercial dynamics of the most successful economic organization of the period. robert parthesius Robert Parthesius is a naval historian and director of the Centre for International Heritage Activities in Leiden. dutch ships in amsterdam tropical waters studies in the dutch golden age The Development of 978 90 5356 517 9 the Dutch East India Company (voc) Amsterdam University Press Shipping Network in Asia www.aup.nl dissertation 1595-1660 Amsterdam University Press Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters The development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipping network in Asia - Robert Parthesius Founded in as part of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age (Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw) aims to promote the history and culture of the Dutch Republic during the ‘long’ seventeenth century (c. -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind. -

Some Context of Colour and the Dress of the Kandyan

SOME CONTEXT OF COLOUR AND THE DRESS OF THE KANDYAN KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA Gayathri Madubhani Ranathunga Abstract Colour of the dress has been derived through inherited values, customs and norms of culture since time immemorial, ultimately colour, dress, and culture have been interwoven into the lives of the people. The objective of this research is to discuss cultural explanations for how people perceived colour in order to communicate different meanings through dress. The selected study setting is the Kandyan era of Sri Lanka which was the last Kingdom of ancient Sri Lankan administration, extended from 15th century AD to 1815. The era was a well-demarcated of foreign influences in dress. During the reign, both Western and Eastern foreign influences spread over the Kingdom, namely South Indian, Western (Portuguese, Dutch, British), Siamese. These influences have caused a huge impact on Sri Lankan dress in every aspect like novel dress items and patterns, silhouette, accessories, headdress, dress materials and colour. Colour had been a successful stimulus in influencing foreign attire. The analysis is explored through actual descriptions made by observational - participants, historical records, murals of the period, folklore which depicted the dress of the era relevant to the subject. According to the cultural exploration of colour perception, it was found that people perceived colour in a common way although there were some differences in perception at the individual level. As a community people had a common perception of values and norms of a certain colour and that was cleared through common ceremonies like the temple, funeral and marriage ceremonies. Perception of colour is unique to individual cultures.