Los Angeles Historic Resource Survey Report: a Framework for a Citywide Historic Resource Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS/SONY in High Gear W/Japanese Market on Eve Ur Inch Disks Bow

i sh Box Self Service Tape Guide (Turn The Page) ... IS/SONY In High Gear w/Japanese Market On Eve 2nd Spot In Global Disk Sales . The Split Look August 16, 1969 i Top 40 Radio ,;oldners Form ash.,mpany...EVR: )se To A Consumer Reality ... SSS Buys Ott Cash Box754 d Bird, Blue Cat Catalogs ... Mini Players, ur Inch Disks Bow On European Markets... Peter Sarstedt E WONDER: BIG STEVIE WONDER Intl Section Begins on Pg. 61 www.americanradiohistory.com The inevitable single from the group that brought you "Young Girl" and "WomanYVoman:' EC "This Girl Is Dir Ai STA BII aWoman Now7 hbAn. by Gary Puckett COiN and The Union Gap. DEE On Columbia Records* Di 3 II Lodz,' Tel: 11A fie 1%. i avb .» o www.americanradiohistory.com ///1\\ %b\\ ISM///1\\\ ///=1\\\ Min 111 111\ //Il11f\\ 11111111111111 1/11111 III111 MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY ii INTERNATIONAL milli 1IUUIII MI/I/ MIII II MU/// MUMi M1111/// U1111D U IULI glia \\\1197 VOL. XXXI - Number 3/August 16, 1969 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Cash Box Assoc. Editor JOHN KLEIN BOB COHEN BRUCE HARRIS Self- Service EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA Tape Guide ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER, New York BILL STUPER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood Much of the confusion facing first - 8 -TRACK CARTRIDGES: Using the WOODY HARDING unit tape consumers lies in the area same speed and thickness of tape Art Director of purchaser education. -

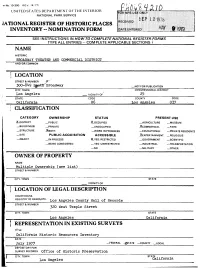

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

32Nd Annual California Preservation Design Awards

32ND ANNUAL CALIFORNIA PRESERVATION DESIGN AWARDS OCTOBER 2, 2015 JULIA MORGAN BALLROOM, MERCHANTS EXCHANGE BUILDING SAN FRANCISCO The Board of Trustees of the California Preservation Foundation welcomes you to the Preservation Design Awards Ceremony Friday, October 2, 2015 Julia Morgan Ballroom, Merchants Exchange Building, San Francisco 6:00 pm Cocktail Reception and Dinner 7:30 pm Welcome Kelly Sutherlin McLeod, FAIA President, Board of Trustees California Preservation Foundation Cindy L. Heitzman, Executive Director, California Preservation Foundation Awards Presentations Presentation of the President’s Award for Lifetime Acheivement John F. Merritt Presentation of the 32nd Annual Preservation Design Awards Kurt Schindler, FAIA, Jury Chair Amy Crain Jeff Greene Leo Marmol, FAIA Chuck Palley Jay Reiser, S.E. Annual Sponsors Cornerstone Spectra Company Cornice Architectural Resources Group IS Architecture Cody Anderson Wasney Architects, Inc. Kelly Sutherlin McLeod Architecture, Inc. EverGreene Architectural Arts Kitson Contracting, Inc. Garavaglia Architecture Page & Turnbull GPA Consulting Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, Inc. Historic Resources Group Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. Holmes Culley/Holmes Fire 2 Preservation Design Awards 2015 Preservation Design Awards Sponsors Pillar Kelly Sutherlin McLeod Architecture, Inc. Plant Construction Marmol Radziner Plath and Company, Inc. Supporting AC Martin MATT Construction Corporation Cody | Brock Commercial Builders Rinne & Peterson Structural Engineers Cody Anderson Wasney Architects, Inc. Vallier Design Associates Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. Nonprofit Fort Mason Center 3 Preservation Design Awards 2015 2015 Awards Jury Kurt Schindler, FAIA, LEED AP Principal, ELS Architecture and Urban Design | Awards Chair and PDA Jury Chair Kurt Schindler is a principal at ELS and directs the firm’s historic and seismic renovation projects. -

Earnest 1 the Current State of Economic Development in South

Earnest 1 The Current State of Economic Development in South Los Angeles: A Post-Redevelopment Snapshot of the City’s 9th District Gregory Earnest Senior Comprehensive Project, Urban Environmental Policy Professor Matsuoka and Shamasunder March 21, 2014 Earnest 2 Table of Contents Abstract:…………………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….5 Literature Review What is Economic Development …………………………………………………………5 Urban Renewal: Housing Act of 1949 Area Redevelopment Act of 1961 Community Economic Development…………………………………………...…………12 Dudley Street Initiative Gaps in Literature………………………………………………………………………….14 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………15 The 9th Council District of Los Angeles…………………………………………………..17 Demographics……………………………………………………………………..17 Geography……………………………………………………………………….…..19 9th District Politics and Redistricting…………………………………………………23 California’s Community Development Agency……………………………………………24 Tax Increment Financing……………………………………………………………. 27 ABX1 26: The End of Redevelopment Agencies……………………………………..29 The Community Redevelopment Agency in South Los Angeles……………………………32 Political Leadership……………………………………………………………34 Case Study: Goodyear Industrial Tract Redevelopment…………………………………36 Case Study: The Juanita Tate Marketplace in South LA………………………………39 Case Study: Dunbar Hotel………………………………………………………………46 Challenges to Development……………………………………………………………56 Loss of Community Redevelopment Agencies………………………………..56 Negative Perception of South Los Angeles……………………………………57 Earnest 3 Misdirected Investments -

Wyvernwood Garden Apartments Has Fostered a Strong Sense of Community Among Its 6,000 Residents

Volume 33 m a r a p r 2 0 1 1 Number 2 Last Remaining Seats Turns 25! Member ticket sales start March 30 Celebrate a quarter century of classic films and live entertainment in the historic theatres of Los Angeles! The 25th Annual Last Remaining Seats series takes place May 25 through June 29. You will receive a large postcard in the mail this year in lieu of a brochure; you can find all the details and order tickets starting March 30 at laconservancy.org. We were finalizing the schedule at press time; it should be online by the time you receive this newsletter. In addition to the six Wednesday evening screenings, this special season will include a bonus Fan Favorite film (Sunset Boulevard, Despite its vast size, Wyvernwood Garden Apartments has fostered a strong sense of community among its 6,000 residents. Clockwise from top left: Historic view of the complex (Security Pacific Collection/Los Angeles Public selected by you, our members!). It will screen Library); current residents (Jesus Hermosillo); a resident sends a message (Evangelina Garza); teenager Juan twice (matinee and evening shows) at the Pal- Bucio’s depiction of what Wyvernwood means to him; young residents (Molly Mills). ace Theatre on Sunday, June 26, a hundred years to the day after it opened! We’ll be at the Wyvernwood Garden Apartments: Palace as part of a broader celebration of the centennial of several theatres on Broadway. Remember to take part in our 2011 mem- Community by Design bership drive for your chance to win VIP by Cindy Olnick and Karina Muñiz tickets to a Last Remaining Seats screening. -

The Dunbar Hotel and the Golden Age of L.A.’S ‘Little Harlem’

SOURCE C Meares, Hadley (2015). When Central Avenue Swung: The Dunbar Hotel and the Golden Age of L.A.’s ‘Little Harlem’. Dr. John Somerville was raised in Jamaica. DEFINITIONS When he arrived in California in 1902, he was internal: people, actions, and shocked by the lack of accommodations for institutions from or established by people of color on the West Coast. Black community members travelers usually stayed with friends or relatives. Regardless of income, unlucky travelers usually external: people, actions, and had to room in "colored boarding houses" that institutions not from or established by were often dirty and unsafe. "In those places, community members we didn't compare niceness. We compared badness," Somerville's colleague, Dr. H. Claude Hudson remembered. "The bedbugs ate you up." Undeterred by the segregation and racism that surrounded him, Somerville was the first black man to graduate from the USC dental school. In 1912, he married Vada Watson, the first black woman to graduate from USC's dental school. By 1928, the Somervilles were a power couple — successful dentists, developers, tireless advocates for black Angelenos, and the founders of the L.A. chapter of the NAACP. As the Great Migration brought more black people to L.A., the city cordoned them off into the neighborhood surrounding Central Avenue. Despite boasting a large population of middle and upper class black families, there were still no first class hotels in Los Angeles that would accept blacks. In 1928, the Somervilles and other civic leaders sought to change all that. Somerville "entered a quarter million dollar indebtedness" and bought a corner lot at 42nd and Central. -

Gwendolyn Wright

USA modern architectures in history Gwendolyn Wright REAKTION BOOKS Contents 7 Introduction one '7 Modern Consolidation, 1865-1893 two 47 Progressive Architectures, ,894-'9,8 t h r e e 79 Electric Modernities, '9'9-'932 fau r "3 Architecture, the Public and the State, '933-'945 fi ve '5' The Triumph of Modernism, '946-'964 six '95 Challenging Orthodoxies, '965-'984 seven 235 Disjunctures and Alternatives, 1985 to the Present 276 Epilogue 279 References 298 Select Bibliography 305 Acknowledgements 3°7 Photo Acknowledgements 3'0 Index chapter one Modern Consolidation. 1865-1893 The aftermath of the Civil War has rightly been called a Second American Revolution.' The United States was suddenly a modern nation, intercon- nected by layers of infrastructure, driven by corporate business systems, flooded by the enticements of consumer culture. The industrial advances in the North that had allowed the Union to survive a long and violent COll- flict now transformed the country, although resistance to Reconstruction and racial equality would curtail growth in the South for almost a cen- tury. A cotton merchant and amateur statistician expressed astonishment when he compared 1886 with 1856. 'The great railway constructor, the manufacturer, and the merchant of to-day engage in affairs as an ordinary matter of business' that, he observed, 'would have been deemed impos- sible ... before the war'? Architecture helped represent and propel this radical transformation, especially in cities, where populations surged fourfold during the 30 years after the war. Business districts boasted the first skyscrapers. Public build- ings promoted a vast array of cultural pleasures) often frankly hedonistic, many of them oriented to the unprecedented numbers of foreign immi- grants. -

NEWS from the GETTY DATE: June 10, 2009 for IMMEDIATE RELASE

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY DATE: June 10, 2009 FOR IMMEDIATE RELASE GETTY PARTICIPATES IN 2009 GUADALAJARA BOOK FAIR Getty Research Institute and Getty Publications to help represent Los Angeles in the world’s largest Spanish-language literary event Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles At the Museo de las Artes, Guadalajara, Mexico November 27, 2009–January 31, 2010 LOS ANGELES—The Getty today announced its participation in the 2009 International Book Fair in Guadalajara (Feria Internacional del Libro de Guadalajara or FIL), the world’s largest Spanish-language literary event. This year, the city of Los Angeles has been invited as the fair’s guest of honor – the first municipality to be chosen for this recognition, which is usually bestowed on a country or a region. Both Getty Publications and the Getty Research Institute (GRI) will participate in the fair for the first time. Getty Publications will showcase many recent publications, including a wide selection of Spanish-language titles, and the Getty Research Institute will present the extraordinary exhibition, Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles, which includes 110 rarely seen photographs from the GRI’s Julius Shulman photography archive, which was acquired by the Getty Research Institute in 2005 and contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies. “We are proud to help tell Los Angeles’ story with this powerful exhibition of iconic and also surprising images of the city’s growth,” said Wim de Wit, the GRI’s senior curator of architecture and design. -

The German/American Exchange on Nazi-Era Art Provenance Research

2017 PREP Exchanges The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (February 5–10) Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (September 24–29) 2018 PREP Exchanges The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (February 25–March 2) Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich (October 8–12) 2019 PREP Exchanges Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Spring) Smithsonian Institution, Provenance Research Initiative, Washington, D.C. (Fall) Major support for the German/American Provenance Research Exchange Program comes from The German Program for Transatlantic Encounters, financed by the European Recovery Program through Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, and its Commissioner for Culture and the Media Additional funding comes from the PREP Partner Institutions, The German/American Exchange on the Smithsonian Women's Committee, James P. Hayes, Nazi-Era Art Provenance Research Suzanne and Norman Cohn, and the Ferdinand-Möller-Stiftung, Berlin 3RD PREP Exchange in Los Angeles February 25 — March 2, 2018 Front cover: Photos and auction catalogs from the 1910s in the Getty Research Institute’s provenance research holdings The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive Los Angeles, CA 90049 © 2018Paul J.Getty Trust ORGANIZING PARTNERS Smithsonian Provenance Research Initiative, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz—Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation—National Museums in Berlin) PARTNERS The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Getty Research -

The Artist Creating a 150-Foot-Long Glass Rainbow

The Artist Creating a 150-Foot-Long Glass Rainbow nytimes.com/2019/02/07/t-magazine/sarah-cain-san-francisco-airport.html By Alice Newell-Hanson February 6, 2019 The first paintings that Sarah Cain remembers admiring as a teenager were works by Joan Mitchell, Philip Guston and Robert Motherwell which, thanks to a public arts fund, lined the walls of an otherwise dismal underground mall in Albany, N.Y., not far from where she grew up, in Kinderhook. “My parents didn’t really take me to museums, so that is where I saw the first real art, mixed in with shops and a McDonald’s,” says Cain, who is now 40 and an established artist herself. In July, she will unveil a major public work of her own, a 150-foot-long series of 37 vividly colorful stained-glass windows, funded by the San Francisco Arts Commission, which she hopes will inspire passers-by in an equally unlikely setting: the new AirTrain terminal at the city’s international airport. Cain lived in San Francisco for 10 years in the late 1990s and early 2000s; she studied art at the San Francisco Art Institute, and later Berkeley, then stayed in the area, making ephemeral large-scale paintings inside the abandoned buildings where her artist friends squatted. The San Francisco airport installation, her first permanent public work, channels the outsider ethos of 1/3 those early pieces as well as the rainbow-colored prismatic compositions of her more recent paintings and drawings, but stained glass is a relatively new medium for her. -

Nomination Form, “The Tuckahoe Apartments.” (14 June 2000)

NPS Form 10- 900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Fonn (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ...................................................... - - - ...........................................................................................................................................................................1. Name of Property historic name John Rolfe Apartments other nameslsite number DHR # 127-6513 ---------- 2. Location street & number 101 Tem~sfordLane not for publication NIA city or town Richmond vicinity state Virqinia code & county Independent Citv code 760 zip code 23226 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Presewation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this