A Semiotic Approach (A Video Tape Presentation)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of the Color Green in Shakespeare

Representations of the Color Green in Shakespeare MATSUDA Misako The color symbolism in English Renaissance literature is no longer innovating topic for students of literary history,1 however, figurative meaning of colors in literary works from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century deserves further research for the understanding of complicated changing symbolism of colors. As Don Camerron Allen points out, the English poets learned continental color symbolism, and applied it to their works. He lists four treatises which serves as the main stock of the color imagery for the English writers: Alciatus’Emblemata, Giovanni de Rinaldi’s Il mostruossimo mostro (1592), Fulvio Pellegrino’s Significato de’ Colori e di’ Mazzolli (1593), a commentary on a popular sonnet; and a Trattato dei Colori di Sicille Araldo del Alfonso d’ Aragona.2 Among these, Sicille Araldo is one of the most influential writings on colors, which Cesare Ripa consulted when he compiled Iconologia.3 Jean Courtois’s Le Blason des Couleurs, the French version of Sicille Araldo, was written in French in 1435―58. It was first published in 1495 in Paris, and the enlarged edition was published in the beginning of sixteenth century. In France the book was reprinted at least fourteen times by the end of the sixteenth century.4 The book also became popular in Italy during the sixteenth century where it was reprinted six times. These Italian and French treatises discuss colors in terms of their physical substance and psychological effect. Colors are not just colors, but different colors were associated with different human sentiments. Each color has had several figurative meanings from classical times, and was related to each other to represent inward passions, virtues and vices. -

On the Symbolism of Color in Dubliners

US-China Foreign Language, June 2018, Vol. 16, No. 6, 343-346 doi:10.17265/1539-8080/2018.06.007 D DAVID PUBLISHING On the Symbolism of Color in Dubliners ZHANG Tian-yi, JIA Xiao-yun University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China This article researches the function of color symbols on expressing the theme by analyzing the original text. By doing such researches, the relationship of symbol with deepening the theme can be clearly revealed. Keywords: Dubliners, Jam Joyce, color symbolism Introduction In creating Dubliners, Jam Joyce chooses the capital of Ireland as its background and vividly describes various kinds of lifestyle and mentation in order to uncover the numbness of people and paralysis of the whole society. This short story made up of 15 stories displays the fierce conflict between people and the whole society and the bitter feeling after failure (Qiang, 2004). Color Symbols As one of the important rhetoric method, color symbol has strong metaphorical meaning. It is often used to describe abstract things and people’s character, living features and mood, which makes the expression vividly (Li, 2007). Different colors brings various kinds of feelings for human beings, this is to say, different colors represent different moods, so we can judge moods, beliefs, nature of people through colors. In this novel, the author uses a lot of colors to vividly express the numbness of people in current society as a result of the brutal war. It’s very hard for people to gain confidence after war. So most people remain stagnate to escape the pain brought by the sufferings. -

A Brief History of Colour, the Environmental Impact of Synthetic Dyes and Removal by Using Laccases

molecules Review A Brief History of Colour, the Environmental Impact of Synthetic Dyes and Removal by Using Laccases Leidy D. Ardila-Leal 1, Raúl A. Poutou-Piñales 1,*,† , Aura M. Pedroza-Rodríguez 2 and Balkys E. Quevedo-Hidalgo 3 1 Grupo de Biotecnología Ambiental e Industrial (GBAI), Laboratorio de Biotecnología Molecular, Departamento de Microbiología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (PUJ), Bogotá 110-23, DC, Colombia; [email protected] 2 Grupo de Biotecnología Ambiental e Industrial (GBAI), Laboratorio de Microbiología Ambiental y de Suelos, Departamento de Microbiología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (PUJ), Bogotá 110-23, DC, Colombia; [email protected] 3 Grupo de Biotecnología Ambiental e Industrial (GBAI), Laboratorio de Biotecnología Aplicada, Departamento de Microbiología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (PUJ), Bogotá 110-23, DC, Colombia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Fax: +57-1320-8320 (ext. 4021) † Present address: Carrera 7ma No. 43–82, Edificio 50 Lab. 124, Bogotá 110-23, DC, Colombia. Abstract: The history of colour is fascinating from a social and artistic viewpoint because it shows Citation: Ardila-Leal, L.D.; the way; use; and importance acquired. The use of colours date back to the Stone Age (the first news Poutou-Piñales, R.A.; of cave paintings); colour has contributed to the social and symbolic development of civilizations. Pedroza-Rodríguez, A.M.; Colour has been associated with hierarchy; power and leadership in some of them. The advent Quevedo-Hidalgo, B.E. A Brief of synthetic dyes has revolutionized the colour industry; and due to their low cost; their use has History of Colour, the Environmental spread to different industrial sectors. -

A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Symbolic Meanings of Color

Chang Gung Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 7:1 (April 2014), 49-74 A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Symbolic Meanings of Color Hui-Chih Yu* Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to extend the scope of English knowledge about color so as to arouse the interest of students in learning English through the use of color terms. Color not only fills our world with beauty but provides a source of inspirations, which would stimulate the fancy of students to increase the interest of their life. Color serves as a means of communication. The communicative qualities of a color can be defined in terms of natural and psychological associations. Occurrences of colors in nature are universal and timeless. However, color may generate another level of meaning in the mind. This color symbolism arises from cultural, mythical, historical, religious, political, and linguistic associations. The symbolic meanings of color words reveal wide-ranging connotations in cultures including positive and negative meanings. The paper will examine human cognition of colors, explore the origin of primary colors, and analyze the meaning of color in different cultures. The awareness of how and why colors communicate meaning will be explained. Finally, an approach to teaching students how to use color terms in different situations will be presented. Keywords: Color, Element, Connotation, Symbolism, Mythology * Associate Professor, Department of English, Shih Hsin University, E-mail: [email protected]. The author is thankful to two anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions. Chang Gung Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 7:1 (2014) 1. -

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation As Social Status Symbol During the Roman Empire in the West

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation as Social Status Symbol during the Roman Empire in the West Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Andrew J. Koh, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies by Mary Pons May 2016 Acknowledgments This paper truly would not have come to be without the inspiration provided by Professor Andrew Koh’s Art and Chemistry class. The curriculum for that class opened my mind to a new paradigmatic shift in my thinking, encouraging me to embrace the possibility of reinterpreting the archaeological record and the stories it contains through the lens of quantifiable scientific data. I know that I would never have had the courage to finish this project if it were not for the support of my advisor Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, who never rejected my ideas as outlandish and stayed with me as I wrote and rewrote draft after draft to meet her high standards of editorial excellence. I also owe a debt of gratitude to my parents, Gary and Debbie Pons, who provided the emotional support I needed to get through my bouts of insecurity. When everything I seemed to put on the page never seemed good enough or clear enough to explain my thought process, they often reminded me to relax, sleep, walk away from it for a while, and try again another day. -

Literary Analysis: Color Symbolism in the Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Helium 8 Nov

Yaffe, Kyle. “Literary analysis: Color symbolism in The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Helium 8 Nov. 2008. Web. 29 July 2013. Vibrant, deadly, deceiving, innocent - colors are the dominating symbols utilized by F. Scott Fitzgerald in his masterpiece The Great Gatsby . Daniel J. Schneider, the Chairman of the Department of English for Windham College, states, "The vitality and beauty of F. Scott Fitzgerald's writing are perhaps nowhere more strikingly exhibited than in his handling of the color symbols in The Great Gatsby." Throughout the book characters, places, and objects are given "life" by colors, especially the more prominent ones. The colors of white, yellow, and green are the most eminent, easily distinguishable from the rest, and representing purity, death, and hope. Such strong symbolic colors are seen continually, and exist to provide a higher and more in depth meaning to the book. "White is one of the main symbolic colors in The Great Gatsby, representing purity, innocence, and honesty" (Adam H.). Nick Carraway, Jay Gatsby, Jordan Baker, and Daisy Buchanan all directly exemplify Adam's statement. Nick considers himself the only truly honest person he knows (Fitzgerald 60) and often wears white, such as when he attends one of Gatsby's parties for the first time. This event being considerably significant, Nick wanted to make the best impression he could - that is, appearing untainted and honest - for Gatsby and the other guests. Gatsby also adorns himself in white when he finally reunites with Daisy after five years of separation. "and Gatsby, in a white flannel suit, silver shirt, and gold-colored tie, hurried in" (Fitzgerald 84). -

Aspects of Color Choice and Perception in Ancient Egyptian Painting

Open Archaeology 2018; 4: 173–184 Original Study Meghan E. Strong* Do You See What I See? Aspects of Color Choice and Perception in Ancient Egyptian Painting https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2018-0011 Received June 5, 2017; accepted December 13, 2017 Abstract: Color in ancient Egypt has been examined through linguistics, anthropological theory and archaeological science. In recent years, attention has focused on the application of art historical theories of reception and perception to ancient Egyptian art, but seldom on color itself. This article will examine aspects of color choice and visual perception, particularly focusing on use of the pigments yellow ochre and orpiment. Building on a growing body of art historical and archaeometric scholarship, it will demonstrate the contributions that experimental archaeology can make to the analysis and understanding of ancient Egyptian painting. Specifically, this study will examine why the Egyptian artist chose specific color combinations by taking into account the original space and lighting conditions of these paintings. Keywords: yellow pigment, art historical theory, aesthetics, visual perception, experimental archaeology, artificial light, darkness 1 Introduction The study of prehistoric and ancient Egyptian art has followed similar trajectories over the past 200 years. From the initial 19th century perception of crude Paleolithic figures as “art for art’s sake”, scholarship has evolved to appreciate the craftsmanship and aesthetic qualities of these pieces, while at the same time considering the environmental, magical, ritual and mundane aspects of Paleolithic art. Examination of ancient Egyptian art had similarly humble beginnings. The first scholar to specifically address the topic, Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), suggested that the deficiency in the ancient Egyptian figural form must be due to the unappealing body shape of the Egyptians themselves (Winckelmann, 1764). -

Color Symbolism in Hinduism

Color Symbolism in Hinduism For the Hindu, colors play a very important role in the religion and culture and have a very deep significance, transcending purely decorative values. Hindu artists use color on the deities and their dresses signifying their qualities. Proper use of colors creates an environment, which should keep a person cheerful. Some of the main colors used in religious ceremonies are red, yellow (turmeric), green from leaves, white from wheat flour. etc. Red indicates both sensuality and purity. In Hindu religion, red is of utmost significance and the color most frequently used for auspicious occasions like marriages, birth of a child, festivals, etc. A red mark is put on the forehead during ceremonies and important occasions. As a sign of marriage, women put red powder on the hair parting. They also wear a red sari during marriage. Red powder is usually thrown on statues of deities and phallic symbols during prayers. It is also the color of Shakti (prowess). A red colored dress is put on deities who are charitable, brave, protective, and who have the capacity to destroy evil. On the death of a woman, her body is wrapped in a red cloth for the cremation. Saffron The most sacred color for the Hindu saffron. Represents fire and as impurities are burnt by fire, this color symbolizes purity. It also represents religious abstinence. This color connotation has a sacred meaning for the Hindu. It is the color of holy men and ascetics who have renounced the world. Wearing the color symbolizes the quest for light. It is the battle color of the Rajputs, the warrior caste. -

Mapping Ethnicity: Color Use in Depicting Ethnic Distribution

12 cartographic perspectives Number 40, Fall 2001 Mapping Ethnicity: Color Use in Depicting Ethnic Distribution Jenny Marie Johnson Color effects are in the eye of the beholder. Yet the deepest and truest secrets of color effects are, I know, University of Illinois at invisible even to the eye, and are beheld by the heart alone. Urbana-Champaign (Itten 1970) Maps are made for a specific purpose, or set of purposes. No individual cartographer or cartography-producing organization produces a map just for the sake of producing a map. People and organizations have agendas; maps tell stories. Map stories are told through symbols and colors. Colors have meaning. Perhaps color choice is intended to indi- cate an organization’s attitudes toward the phenomena being mapped. Color on maps of ethnic groups can be evaluated inter-textually by plac- ing the maps into the context of their producers and the time of their production. The colors, and their meanings, that are used to represent particular groups will reflect the map producer’s attitudes toward the ethnic groups. If these attitudes are unknown, they could be hypoth- esized by evaluating color usage. Color choices may act as indicators of opinions otherwise unexpressed. ROLE OF THE ORGANIZATION uch of the thinking about the role that organizations play in produc- ing supposedly scientific maps was done by Harley (1988) during the latter half of his career. He began this work by examining antiquarian maps in a context far greater than the normal “map as beautiful object”. Instead he examined them with the idea that the maps were artifacts produced by agents of organizations with particular goals and objectives. -

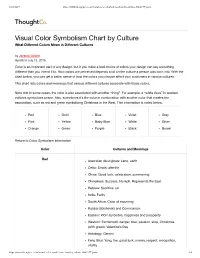

Visual Color Symbolism Chart by Culture What Different Colors Mean in Different Cultures

8/28/2017 https://www.thoughtco.com/visual-color-symbolism-chart-by-culture-4062177?print Visual Color Symbolism Chart by Culture What Different Colors Mean in Different Cultures by Jeremy Girard Updated July 12, 2016 Color is an important part of any design, but if you make a bad choice of colors your design can say something different than you intend it to. How colors are perceived depends a lot on the culture a person was born into. With the chart below, you can get a better sense of how the colors you choose affect your customers in various cultures. This chart lists colors and meanings that various different cultures associate with those colors. Note that in some cases, the color is also associated with another “thing”. For example, a “white dove” in western cultures symbolizes peace. Also, sometimes it’s the color in combination with another color that creates the association, such as red and green symbolizing Christmas in the West. This information is noted below. Red Gold Blue Violet Gray Pink Yellow Baby Blue White Silver Orange Green Purple Black Brown Return to Color Symbolism Information Color Cultures and Meanings Red Australian Aboriginals: Land, earth Celtic: Death, afterlife China: Good luck, celebration, summoning Cherokees: Success, triumph. Represents the East. Hebrew: Sacrifice, sin India: Purity South Africa: Color of mourning Russia: Bolsheviks and Communism Eastern: Worn by brides, happiness and prosperity Western: Excitement, danger, love, passion, stop, Christmas (with green), Valentine’s Day Astrology: Gemini Feng Shui: Yang, fire, good luck, money, respect, recognition, vitality https://www.thoughtco.com/visual-color-symbolism-chart-by-culture-4062177?print 1/6 8/28/2017 https://www.thoughtco.com/visual-color-symbolism-chart-by-culture-4062177?print Psychology: Stimulates brain wave activity, increases heart rate, increases blood pressure Roses: Love, respect — red and yellow together means gaiety, joviality Stained Glass (Dante): Divine love, the Holy Spirit, courage, self- sacrifice, martyrdom. -

Dan Collins, Coordinator Studio Core Program School of Art Arizona State University COURSE SYNOPSIS: ART 113 (COLOR)

Color Dan Collins, Coordinator Studio Core Program School of Art Arizona State University COURSE SYNOPSIS: ART 113 (COLOR) Unit I: Subjective Color Unit II: Emotional/Symbolic Color Unit III: Color Basics: Additive Color (Light Theory) Unit IV: Color Basics: Subtractive Color (Pigment Theory) Unit V: Color Schemes and Beyond Unit VI: Local and Optical Color Unit VII: Joseph Albers and Color Unit VIII: Depth Cues in Color Unit IX: Color as a Compositional Device Unit X: Process Color Unit XI: Final Project Optional Unit: The Psychology of Color ART 113 (COLOR) A Course Outline for Teaching Assistants and Faculty Dan Collins, Studio Core Coordinator Catalog description: Principles of color theory as related to the visual arts. Prerequisites: ART 111 and ART 112. Six hours a week. Expanded description: This course shall cover not only the basic elements of color theory, but also provide an opportunity for the more intuitive and practical applications of color in the making of art. The perceptual, symbolic, and cultural significances of color are addressed. Required text Color, Zelanski and Fisher, Prentice-Hall, Fourth Edition, 2003 General Introduction for the Instructor “Color is the most relative medium in art” —Josef Albers “The artist is a medium.” —Marcel Duchamp Art 113—Color—is one of a quartet of courses comprising the Studio Core Curriculum in the School of Art. The Foundation as a whole is designed to both provide a practical understanding of Drawing, 2-D Design, 3-D Design, and Color and to whet the appetite for more advanced courses. A thoughtful, well- ordered problem-solving structure in each sixteen-week course, within the context of an integrated "first year" curriculum, provides an essential foundation for the variety of specialized courses found in the School of Art. -

Onomasiological and Semasiological Aspects

56 Onomasiology Online 5 (2004): 56-139 MARION MATSCHI COLOR TERMS IN ENGLISH: ONOMASIOLOGICAL AND SEMASIOLOGICAL ASPECTS Abstract The following article is a master’s thesis on color terms in English language history. Within Berlin and Kay’s eleven basic color categories, and various non-basic, secondary, or specialized expressions are analyzed regard- ing their origin and underlying motives of formation: Inherited terms are described from an onomasiological point of view, thus starting from the respective concept or image, whereas loanwords are dealt with separately as their motivations are often unclear to the speaker. As the color systems of Old and Modern English are encoded differently, it is investigated how transitional stages and nuances of color are represented in the re- spective periods. Finally, interesting semasiological aspects are given as well. The study shows that, resulting from a huge need of new color names due to economical and cultural changes, many color terms were borrowed from French and Latin, but even more are a product of metonymical exten- sions of entity senses. By means of this, all kinds of images and concepts (e.g. plants, animals, food etc.) can be utilized to designate color. However, they are often restricted, remain unknown to the layperson, and can disappear very quickly (e.g. fashion and car color terms). ABBREVIATIONS1 AN Anglo-Norman BCT Basic Color Term Da Danish Du Dutch EDD The English Dialect Dictionary F French FEW Französisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch G German Gmc Germanic Goth Gothic IE Indo-European IEW Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch It Italian L Latin Lith Lithuanian LL Late Latin ME Middle English MED Middle English Dictionary MIr Medieval Irish ML Medieval Latin ModE Modern English ODEE The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology OE Old English OEC Dictionary of Old English Corpus OED The Oxford English Dictionary OF Old French OFris Old Frisian OHG Old High German OI Old Icelandic OIr OldIrish 1For full bibliographic details of published titles, see the Bibliography.