Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ÿþ< 4 D 6 9 6 3 7 2 6 F 7 3 6 F 6 6 7 4 2 0 5 7 6 F 7 2 6 4 2 0 2 D 2 0 C D F 8 C 2 E 7 D 6 D 0 D 0 C 4 D 5 B D D 3 E B

《海军新军事变革丛书》第二批总序 ·1· Network Centric Warfare and Coalition Operations 网络中心战与联盟作战 [加]Paul T. Mitchell 著 邢焕革 周厚顺 周 浩 主译 唐宗礼 主审 ·2· 网络中心战与联盟作战 Network Centric Warfare and Coalition Operations: The new military operating system / by Paul T. Mitchell / ISBN: 978-0-415-44645-7 © 2009 Paul T. Mitchell All Rights Reserved. Authorised translation from the English language edition published by Routledge, a member of the Taylor & Francis Group. All rights reserved. 本书原著由 Taylor & Francis 出版集团旗下 Routledge 公司出版,并经其授权翻译出版,版权所有,侵权必究。 Publishing House of Electronics Industry is authorized to publish and distribute exclusively the Chinese (Simplified Characters) language edition. This edition is authorized for sale throughout Mainland China. No part of the publication may be reproduced or distributed by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 本书中文简体翻译版授权由电子工业出版社独家出版并限在中国大陆地区销售。未经出 版者书面许可,不得以任何方式复制或发行本书的任何部分。 Copies of this book sold without a Taylor & Francis sticker on the cover are unauthorized and illegal. 本书封面贴有 Taylor & Francis 公司防伪标签,无标签者不得销售。 版权贸易合同登记号:图字 01-2013-4385 图书在版编目(CIP)数据 网络中心战与联盟作战/(加)米切尔(Mitchell,P.T.)著;邢焕革等译. —北京:电子工业出版社,2013.8 (海军新军事变革丛书) 书名原文:Network Centric Warfare and Coalition Operations: The new military operating system ISBN 978-7-121-21056-3 Ⅰ. ①网… Ⅱ. ①米… ②邢… Ⅲ. ①计算机网络-应用-联合作战-研究 Ⅳ. ①E837-39 中国版本图书馆 CIP 数据核字(2013)第 168252 号 责任编辑:张 毅 文字编辑:王 倩 印 刷:三河市鑫金马印装有限公司 装 订:三河市鑫金马印装有限公司 出版发行:电子工业出版社 北京市海淀区万寿路 173 信箱 邮编:100036 开 本:720×1000 1/16 印张:16.5 字数:238 千字 印 次:2013 -

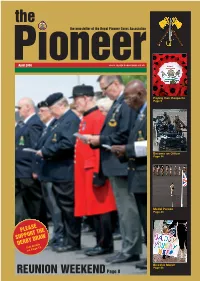

The Pioneerthe Newsletter of the Royal Pioneer Corps Association April 2010

the Pioneerthe newsletter of the Royal Pioneer Corps Association April 2010 www.royalpioneercorps.co.uk Paying their Respects Page 5 Become an Officer Page 14 Medal Parade Page 34 PLEASE SUPPORT THE DERBY DRAW Full details on Page 12 Bicester March Page 36 REUNION WEEKEND Page 8 the please send your cheques payable to RPC Association with your order... Pioneer association shop ▲ Buttons ▲ Cufflinks ▲ Cufflinks ▲ Tie Pin ▲ Tie Pin both badges new badge bronze lovely lovely available £5 £6 £2.50 £2.00 £1.50 each or 6 for £8 ▲ Corps Tie Two different styles are available. One with the older ‘Blackpool Tower’ cap badge and one with the newer cap badge. £8.50 each ▲ Wall Shields ▲ Wall Shields hand painted 85-93 badge £20 £20 ▲ “No Labour, Blazer No Battle” ▲ Badge Military Labour silk & wire during the first £8 World War by John Starling and Ivor Lee A new addition to the shop and only just published. Price includes a £10 donation to the RPC Association. Hardback. £30 ▲ “A War History of the Royal Pioneer Corps 1939-45” by Major E H Rhodes Blazer Wood ▲ Badge This book, long out of silk & wire print, is now available on CD-Rom at a cost of £8 £11 ▲ “Royal Pioneers 1945-1993” by Major Bill Elliott The Post-War History of the Corps was written by Blazer Major Bill Elliott, who ▲ generously donated his Badge work and rights entirely silk & wire for the Association’s benefit. It was published ▲ Bronze Statue £7 by Images, Malvern in why not order & collect at May 1993 and is on sale Reunion Weekend to save in the book shops at £24. -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 34 / PCEMIN 34 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES DOCTRINE OR DOGMA: THE DECISION MAKING PROCESS OF THE CONTEMPORARY OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 22 April 2008 By/par Major D.J. Cross This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. The paper is a scholastic document, and thus L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au contains facts and opinions, which the author cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and correct for que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et the subject. -

Counter Insurgency Operations, and Uses the U.S

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY COLONEL ALEXANDER ALDERSON THE VALIDITY OF BRITISH ARMY COUNTERINSURGENCY DOCTRINE AFTER THE WAR IN IRAQ 2003-2009 DEFENCE ACADEMY COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY PhD THESIS CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY DEFENCE ACADEMY COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF APPLIED SCIENCE, SECURITY AND RESILIENCE PhD THESIS Academic Year 2009-2010 Colonel Alexander Alderson The Validity of British Army Counterinsurgency Doctrine after The War in Iraq 2003-2009 Supervisor: Professor E R Holmes November 2009 © Cranfield University 2009. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner Abstract This thesis analyses whether the British Army’s doctrinal approach for countering insurgency is still valid in the light of the war in Iraq. Why is this important? Insurgency remains a prevalent form of instability. In the absence of a major conventional threat to British security, it is one which is likely to confront the Army for the foreseeable future. If British doctrine for counterinsurgency has been invalidated by the campaign in Iraq, this will have profound implications for the way the Army approaches, and is organized, equipped and trained for counterinsurgency in the future. If the doctrine is found to be valid, another explanation has to be found to account for the conduct and outcome of British operations in Southern Iraq between 2003 and 2009. Using historiographical techniques, the thesis examines the principal influences on extant British doctrine, developed in 1995. It analyzes the principal British manuals, the influence on doctrine of the campaigns in Malaya and Northern Ireland and the theories of Sir Robert Thompson and Gen. -

REGIMENTS and COMMANDING OFFICERS, 1960- 1964-70: in September 1964, One Month Before the Conservative Government Was Replaced B

REGIMENTS AND COMMANDING OFFICERS, 1960- 1964-70: In September 1964 , one month before the Conservative Government was replaced by a Labour Government, the Royal Anglian Regiment had been formed by the merger of the 1 st East Anglian Regiment, the 2 nd East Anglian Regiment, the 3 rd East Anglian Regiment with the Royal Leicestershire Regiment as a three battalion regiment with 4 th Battalion (Leicestershire) at company strength. The Labour Government continued this process with the formation of the Royal Green Jackets in January 1966 at two battalion strength out of the former three battalions of Green Jackets. Queen’s Regiment was created in December 1966 with the amalgamation of the Queen’s Royal Surrey Regiment, the Queen’s Own Buffs (the Royal Kent Regiment), the Royal Sussex Regiment and the Middlesex Regiment. In April 1968 the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers as a three battalion regiment was created through the amalgamation of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, the Royal Warwickshire Fusiliers. The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) and the Lancashire Fusiliers In May 1968 the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) disbanded. In July 1968 the Royal Irish Rangers were formed as a two battalion regiment through the amalgamation of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Royal Ulster Rifles and the Royal Irish Fusiliers. In the same month the three battalion Light Infantry was created through the merger of the Somerset and Cornwall Light Infantry, the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, and the Durham Light Infantry. In September 1968 the 2 nd Battalion, 10 th Princess Mary’s Own Gurkha Rifles was disbanded. -

Army July 12.Indd

THE SOLDIERS’ GAME THE MAGAZINE OF THE ARMY FA Issue 10 – Summer Edition 2012 IN THIS ISSUE INTERNATIONAL STALEMATE AT ALDERSHOT TOWN ARMY WOMEN SHOW HOW IT’S DONE 27TH REGT TAKE TITLE AFTER EIGHT GOAL THRILLER ROYAL SIGNAL AND THE TRIP OF A LIFETIME UNBEATEN, UNBOWED AND PLENTY TO PLAY FOR IN 2013 www.armyfa.com FOOTBALL AArmy_Julyrmy_July 112.indd2.indd 1 227/07/20127/07/2012 113:203:20 VIRTUAL CLUB The UK’s leading publishers for grassroots sporting organisations HANDBOOKS FROM VIRTUAL CLUB HANDBOOK £120 plus VAT Ever thought of producing a club handbook? )DLUIRUG7RZQ<RXWK )RRWEDOO&OXE If not, why not, when you consider all the &OXE+DQGERRN benefi ts a virtual club handbook can off er. A club handbook is the best medium to inform all club members, potential club members and sponsors what your club is about and how it is run. 0$,16321625 BENEFITS OF THE E-SPORTS VIRTUAL HANDBOOK SYSTEM 1. The handbook system is an artworking tool, which allows you to format and produce a club handbook on your PC. All you need is a basic understanding of Word and to use Internet Explorer as your web browser. 2. If you are a Charter Standard club, the club handbook will tick a number of audit boxes. 3. You have access to an FA library of rules, codes and information pages including football ads for such things as Safeguarding, Respect, Kick it Out, Get into Football and FA.com 4. Once completed and signed off , you will receive your virtual handbook within 48 hours.