Buckland, a Catholic Stronghold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2013 Thanksgivings and Baptisms with Revd Eddy

STANFORD IN THE VALE WITH Sunday 7th July Trinity 6 8.30 am Holy Communion (Goosey) GOOSEY & HATFORD 9.45 am Just Come (Stanford) 10.15 am Parish Communion (Stanford) PARISH NEWSLETTER St. Denys Kids each Sunday during term time, except when Family Service, where during the main Parish Communion Service the children go to the Village Hall. Contact 718784 Open House On most Saturdays St Denys’ Church is open between 10 am and noon for coffee and tea, cake and chat. No charge. Do pop in. You’ll find a warm and friendly welcome. This is a good time to talk to discuss weddings, June 2013 thanksgivings and baptisms with Revd Eddy SERVICES FOR THE MONTH FROM THE REGISTERS nd Sunday 2 June Trinity 1 Funeral Service 8.30 am Holy Communion (Goosey) Monday 29th April 9.45 am Just Come (Stanford) Elizabeth Dunkanna Soulsby 10.15 am Parish Communion (Stanford) Huntersfield Aged 99 years th Tuesday 4 June 3.00 pm Time for God (Stanford) Marriage Service th Thursday 6 June Saturday 4th May 2.30 pm Holy Communion at the Grange Mark Pembroke and Jayne Eltham th Sunday 9 June Trinity 2 Baptism 8.30 am Holy Communion (Hatford) Sunday 19th May 9.45 am Just Come (Stanford) Bailey Matthew Rolls 10.15 am Parish Communion (Stanford) Archie Anker at All Saints, Goosey 6.00 pm Evening Prayer (Stanford) WHO’S WHO IN THE PARISH? Wednesday 12th June Priest-in-Charge 10.30 am Holy Communion (Stanford) The Revd Paul Eddy 710267 th Assistant (part-time) Curate – Sunday 16 June Trinity 3 The Revd. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

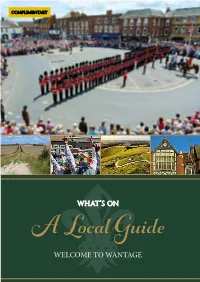

Welcome to Wantage

WELCOME TO WANTAGE Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com Welcome to Wantage in Oxfordshire. Our local guide is your essential tool to everything going on in the town and surrounding area. Wantage is a picturesque market town and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse and is ideally located within easy reach of Oxford, Swindon, Newbury and Reading – all of which are less than twenty miles away. The town benefits from a wealth of shops and services, including restaurants, cafés, pubs, leisure facilities and open spaces. Wantage’s links with its past are very strong – King Alfred the Great was born in the town, and there are literary connections to Sir John Betjeman and Thomas Hardy. The historic market town is the gateway to the Ridgeway – an ancient route through downland, secluded valleys and woodland – where you can enjoy magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse, observe its prehistoric hill figure and pass through countless quintessential English country villages. If you are already local to Wantage, we hope you will discover something new. KING ALFRED THE GREAT, BORN IN WANTAGE, 849AD Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com 3 WANTAGE THE NUMBER ONE LOCATION FOR SENIOR LIVING IN WANTAGE Fleur-de-Lis Wantage comprises 32 beautifully appointed one and two bedroom luxury apartments, some with en-suites. -

Sir Robert Throckmorton (1510-1581)

Sir Robert Throckmorton (1510-1581) William Norwood, Dorothy Spann CENTER's eighth great grandfather and father of Richard Norwood appearing in the lower right in the tree for Captain Richard Spann, was the son of Henry Norwood and Catherine Thockmorton. Catherine Thockmorton was the daughter of Robert Thockmorton and Muriel Berkeley. Sir Robert Thockmorton: Birth: 1510 Alcester; Warwickshire, England Death: Feb. 12, 1581 Alcester; Warwickshire, England St Peters Church, Coughton, Warwickshire, England where he is buried. Sir Robert Throckmorton of Coughton Court, was a distinguished English Tudor courtier. Sir Robert was the eldest son and heir of Sir George Throckmorton (d.1552) by Katherine Vaux, daughter of Nicholas Vaux, 1st Baron Vaux of Harrowden (d.1523). He had many brothers, the most notable being, in descending seniority: Sir Kenelm, Sir Clement Throckmorton MP, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton(1515-1571), Thomas, Sir John Throckmorton(1524-1580), Anthony and George. Robert Throckmorton may have trained at the Middle Temple, the inn attended by his father. At least three of his younger brothers and his own eldest son studied at Middle Temple, but as the heir to extensive estates he had little need to seek a career at court or in government. He was joined with his father in several stewardships from 1527 and was perhaps the servant of Robert Tyrwhitt, a distant relative by marriage of the Throckmortons, who in 1540 took an inventory of Cromwell's goods at Mortlake. He attended the reception of Anne of Cleves and with several of his brothers served in the French war of 1544. Three years later he was placed on the Warwickshire bench and in 1553 was appointed High Sheriff of Warwickshire. -

Notice of Election Vale Parishes

NOTICE OF ELECTION Vale of White Horse District Council Election of Parish Councillors for the parishes listed below Number of Parish Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be Parishes Councillors to be elected elected Abingdon-on-Thames: Abbey Ward 2 Hinton Waldrist 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Caldecott Ward 4 Kennington 14 Abingdon-on-Thames: Dunmore Ward 4 Kingston Bagpuize with Southmoor 9 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Ock Ward 2 Kingston Lisle 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Wildmoor Ward 1 Letcombe Regis 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Northcourt Ward 2 Little Coxwell 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Peachcroft Ward 4 Lockinge 3 Appleford-on-Thames 5 Longcot 5 Appleton with Eaton 7 Longworth 7 Ardington 3 Marcham 10 Ashbury 6 Milton: Heights Ward 4 Blewbury 9 Milton: Village Ward 3 Bourton 5 North Hinksey 14 Buckland 6 Radley 11 Buscot 5 Shrivenham 11 Charney Bassett 5 South Hinksey: Hinksey Hill Ward 3 Childrey 5 South Hinksey: Village Ward 3 Chilton 8 Sparsholt 5 Coleshill 5 St Helen Without: Dry Sandford Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Hill Ward 4 St Helen Without: Shippon Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Village Ward 3 Stanford-in-the-Vale 10 Cumnor: Dean Court Ward 6 Steventon 9 Cumnor: Farmoor Ward 2 Sunningwell 7 Drayton 11 Sutton Courtenay 11 East Challow 7 Uffington 6 East Hanney 8 Upton 6 East Hendred 9 Wantage: Segsbury Ward 6 Fyfield and Tubney 6 Wantage: Wantage Charlton Ward 10 Great Coxwell 5 Watchfield 8 Great Faringdon 14 West Challow 5 Grove: Grove Brook Ward 5 West Hanney 5 Grove: Grove North Ward 11 West Hendred 5 Harwell: Harwell Oxford Campus Ward 2 Wootton 12 Harwell: Harwell Ward 9 1. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Primary Care in OX12 Primary Care in This OX12 Area and for Some

Primary care in OX12 Primary care in this OX12 area and for some inhabitants of Stanford in the Vale takes place from the Mably Way Health Centre, Mably Way, Wantage between two practices, Church Street and Newbury Street. These practices have now joined to become a Primary Care Network. Newbury Street practice took patients from Grove when its practice closed several years ago. This merger and the increasing population growth in the area have put the two practices under considerable strain especially as the premises are inadequate for the number of patients to be served. Although Church Street has reconfigured to produce another consulting room, “hot desking” has proved the only other option. Some services have had to be moved from the building to make room for more GP consulting space. In 2017 England Health England allowed no extra finance for expansion of the building. The Commissioning Group was contacted by the Church St. Patient group who met with Assura who own the building and since then consultations have taken place to provide adequate expansion of the building. Two years later the talks between the Assura and the OCCG continue but no apparent progress has been made. Continued expansion is taking place with around 5.000 houses imminently being built around Wantage and Grove but many more in the surrounding villages. Concern is being expressed about the increasing average age, we already have above average numbers in the older age groups As more retirement flats are built in the area and a further two care homes, one of which has already been started, are being built Primary Care will be further stretched. -

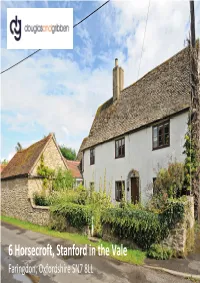

6 Horsecroft, Stanford in the Vale

6 Horsecroft , Stanford in the Vale Faringdon, Oxfordshire SN7 8LL 6 Horsecroft • Stanford in the Vale • Wantage • Oxfordshire • SN7 8LL Guide £695,000 Freehold A fine Grade II listed farmhouse believed to date back c.300 years, situated in the heart of the village, affording a wealth of character together with a generous courtyard with garaging (with permission to convert to residential use), mature gardens, and a generous adjoining self-contained character annexe Farmhouse comprising; five bedrooms, refitted bathroom, three reception rooms, kitchen/breakfast room, utility room, downstairs wet room, oil heating Gardens to the front and rear, large gated courtyard with parking, garage (potential accommodation) double car port with planning to provide double garage/workshop Adjoining self-contained annexe comprising; large bedroom, character loft room, kitchen/dining room, bathroom, sitting room, private courtyard, own access, oil heating LOCATION Stanford in the Vale is an appealing and thriving downland village in the arresting Vale of the White Horse forming part of South Oxfordshire, famous for its ancient prehistoric chalk horse on the South Downs where, it is also believed, St George slayed the dragon. Situated midway between market towns Wantage 6 miles and Faringdon 5 miles, easily accessible from the A417, the village itself caters for day-to-day needs with a modern supermarket, post office, popular primary school and pre-school, village hall and two traditional public houses. Both Wantage and Faringdon offer a further comprehensive range of shopping, leisure and recreational facilities as well as a variety of regular markets and in addition there is a pleasing variety of restaurants and gastro pubs within the surrounding area. -

Stanford in the Vale CE Primary School Prospectus 2020-2021

Stanford in the Vale CE Primary School Prospectus 2020-2021 General Information Headteacher: Mrs Amanda Willis Chair of Governors: Mrs Janet Warren 32 Huntersfield, Stanford in the Vale Telephone: 01367 710789 Address: Stanford in the Vale CE Primary School Stanford in the Vale Faringdon Oxfordshire SN7 8LH Telephone: 01367 710474 (Office hours 8:00am – 4:30pm) Fax: 01367 718429 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.stanford.oxon.sch.uk School Hours Key Stage 1 and Foundation: 9.00am - 12:00pm 1:00pm - 3:10pm 15 minute break in the morning Teaching time 24 hours and 35 minutes per week. (Minimum= 21hrs) Key Stage 2: 9.00am - 12:10pm 1:00pm - 3:15pm 15 minute break in the morning Teaching time 25 hours and 50 minutes per week. (Minimum = 23hrs 30mins) Children may arrive at school no earlier than 8:45am. School size: At present there are 207 pupils on roll (Sept. 2020) Staff Headteacher: Mrs Amanda Willis Assistant Head: Mrs Rachel Cook Teaching Learning Leaders: Mrs Clare Webb Mrs Fay Warner-King Class Teachers: Mrs Rachel Cook & Mrs Kay Adamson - Foundation Mrs Clare Webb & Mrs Naomi Scott – Year 1 Mrs Emma Dickinson – Year 2 Mrs Fay Warner-King & Mrs Katy Watkin – Year 3 Miss Nadja Middleton (Maternity Cover for..) Miss Lucy Bowden – Year 4 Mr Duncan Scott – Year 5 Mrs Rebecca Dharmasiri & Mrs Katy Watkin – Year 6 Release Teachers: Mrs Kay Adamson & Mrs Katy Watkin Special Educational Needs Miss Laura Jamison Teacher Teaching Assistants Foundation Mrs Sue Finney & Mrs Sarah Woodyer-Ward Year 1 Mr Mat Godwin Year -

Cleve House KELMSCOTT CLEVE HOUSE KELMSCOTT

Cleve House KELMSCOTT CLEVE HOUSE KELMSCOTT Lechlade 2 miles • Faringdon 5 miles Cirencester 16 miles • Oxford 24 miles (all mileages and times are approximate) A well-proportioned family house in an unspoilt village Entrance hall • Kitchen/ dining room • Sitting room Two additional reception rooms Utility room • Cloakroom 4 bedrooms • 2 bathrooms Private parking • Garden outbuildings • Double Garage DIRECTIONS From Faringdon, take the A417 towards Lechlade. Continuing along this road through Buscot and just over the bridge before you get to Lechlade, turn right signposted to Kelmscott. Proceed down this road and take the first turning into Kelmscott. Pass the pub (The Plough) and you will then see a red telephone box. Go up this lane and the property is the first on the left. SITUATION Kelmscott is a delightful and unspoilt village situated on the Oxfordshire/Gloucestershire border close to the river Thames and about 2 miles from Lechlade. Well known for its association with William Morris, Kelmscott Manor was his country home from 1871 to1896. The village principally comprises Cotswold stone cottages and houses, a well known Public House and Church with medieval wall paintings. The village is well placed midway between the M4 (junction 15) and M40 as well as being close to historic Lechlade and Burford. Cirencester, Cheltenham and Witney offer extensive shopping facilities. There is a mainline station at Swindon, Oxford or Didcot with a regular service to London Paddington taking approximately 60/40 minutes. There is an excellent choice of schools in the area including Hatherop Castle, St Hughs, Cokethorpe as well as the numerous schools in and around Oxford, Abingdon, Cheltenham and Marlborough. -

A Series of Picturesque Views of Seats of the Noblemen

w8^ 1>w_f,\f \ r_^m.: \^n jmi^. / 'b" ^eK\ WrAmimi Vm SIk mSf^^^^ 1^mi^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/seriesofpictures03morr tt < o n oi n ^ ^ERIES OF p^CTOiinooi fiKis Dr PF niliaii m$n PF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. VOL. HI L () N D () N : willi a im mac k 1-. n 7. 1 k. uq, l u dg a t k hill. ki)inhur(;h and dublin. ^ ^32-^ A SERIES OF Y. &. PICTUBESQUE VIEWS OF SEATS OF THE JSrOBLEMEN AND GENTLEMEN" OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. WITH DESCRIPTIVE AND HISTORICAL LETTERPRESS. EDITED BY THE REV. F. O. MORRIS, B.A., AUTHOR OF A "HISTOKV OP BRITISH BIRDS," DEDICATED BY PERMISSION TO HER JIOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY THE QUEEN. VOL. HI. LONDON: WILLIAM MACKENZIE, 69, LUDGATE MILL. EDINBURGH AND DUBLIN. THE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUNG U ^RSITY ^--^ EROyo. UTAH CONTENTS. PAGE —His Royal Highness Sandeingham. the Peixce of "Wales . .1 — CoMPTON Vekney. Lord Willotjghby de Broke .... 3 — . , Castle. of Durham . Lambton Earl . .5 — Mamhead. Newman, Baronet ...... 7 — . , Keele Hall. Snetd . .9 Castle. — of Macclesfield . SHiRBxrEN Earl . H — . "WYifYAED Park. Marquis of Londonderry , . .13 — . HuTTON Hall. Pease . 15 — . MtTNCASTER Castle. Lord Muncaster . .17 . BEAlfTINGHAM ThORPE. SyKES . 19 — Hall. Baron Tollemache . Helmingham . .21 — Trafalgar House. Earl Nelson . 23 — Broughton Castle. Lord Sate and Sele . .25 — . Stowlangtoft Hall. Wilson . 27 — Davenport . Capesthorne. .29 PoWERSCOURT. —VlSCOUNT PoWERSCOURT . 31 — . Studley Castle. Walker . .33 — EsHTON Hall. Wilson, Baronet ..... 35 Towers.—Brooke . Caen Wood . .37 ' — . Birr Castle. Earl of Eosse . 39 ' — . Hall. Newdegate . -

Wootton and Dry Sandford Community Newsletter

Wootton and Dry Sandford Community Newsletter “Be part of it” also available at http://www.woottondrysandfordshippon.co.uk/newsletter SMALL SQUARE ADVERT Published by the Wootton and Dry Sandford Community Centre Dec 2018/Jan 2019 Neighbourhood Plan Update What’s in this month’s 4.4cm x 4.4cm The Neighbourhood Plan has now progressed from issue? (19.36cm²) its publication phase and we will have, hopefully, P2: Community Centre Fund Raising approx. reviewed any comments made, at our meeting on events 21st November. P3: What’s on in the Community The Plan will then be ready for submission to an Centre independent examiner, whom we will chose from a P4: 24th Abingdon (Dry Sandford) list supplied by the Vale of White Horse District Scout Group SMALL HORIZONTAL Council. Wednesday Club Update ADVERT Message from/to the Editor 6.8cm width, 2.9cm depth Whilst we are unsure of the timescales involved we th are pressing to have this completed as soon as P5&6 11 Nov Centenary Celebration (19.72cm²) approx. possible. P7: Thames Valley Action – Fraud History Society Update Meanwhile the LPP2 (The Vale’s Local Plan Part 2) P9: Wootton St Peter’s CE Primary inspector has written a preliminary response to the School News Vale following the recent public examination of that Oxfordshire Fire and Rescue plan. Service – Cooking fires The Inspector appears to have picked up on a Friends of Shippon Update number of issues raised by our NP. His full comments Jumble Sales Extra can be viewed www.whitehorsedc.gov.uk - Local Plan P13: St Helen’s Church 2031 Part 2: Examination -Examination Library List Advice For Dog Owners As there is no WADS newsletter in January, we will P19: Update from Botley Medical ensure that our website is kept fully up to date with Centre any developments in respect of the NP.