5 Site Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Southern Observatory Your Talk

The European Southern Observatory Your talk Your name Overview What is astronomy? ESO history What is ESO? La Silla VLT ALMA E-ELT ESO Visitor Centre | 9 October 2013 Why are we here? What is astronomy? And what it all is good for? ESO Visitor Centre | 9 October 2013 What is astronomy? Astronomy is the study of all celestial objects. It is the study of almost every property of the Universe from stars, planets and comets to the largest cosmological structures and phenomena; across the entire electromagnetic spectrum and more. It is the study of all that has been, all there is and all that there ever will be. From the effects of the smallest atoms to the appearance of the Universe on the largest scales. ESO Visitor Centre | 9 October 2013 Astronomy in the ancient world Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences, dating back to antiquity, with its origins in the religious, mythological, and astrological practices of the ancient civilisations. Early astronomy involved observing the regular patterns of the motions of visible celestial objects, especially the Sun, Moon, stars and naked eye observations of the planets. The changing position of the Sun along the horizon or the changing appearances of stars in the course of the year was used to establish agricultural or ritual calendars. ESO Visitor Centre | 9 October 2013 Astronomy in the ancient world Australian Aboriginals belong to the oldest continuous culture in the world, stretching back some 50 000 years… It is said that they were the first astronomers. “Emu in the sky” at Kuringai National Park, Sydney -Circa unknown ESO Visitor Centre | 9 October 2013 Astronomy in the ancient world Goseck Circle Mnajdra Temple Complex c. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

The CoRoT Legacy Book c The authors, 2016 DOI: 10.1051/978-2-7598-1876-1.c031 III.1 Transit features detected by the CoRoT/Exoplanet Science Team M. Deleuil1, C. Moutou1, J. Cabrera2, S. Aigrain3, F. Bouchy1, H. Deeg4, P. Bord´e5, and the CoRoT Exoplanet team 1 Aix Marseille Universite,´ CNRS, LAM (Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille) UMR 7326, 13388, Marseille, France 2 Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center, Rutherfordstrasse 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany 3 Department of Physics, Denys Wilkinson Building Keble Road, Oxford, OX1 3RH 4 Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain and Universidad de La Laguna, Dept. de Astrof´ısica, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 5 Institut d’astrophysique spatiale, Universite´ Paris-Sud 11 & CNRS (UMR 8617), Bat.ˆ 121, 91405 Orsay, France While this is reliable on a statistical point of view, individ- 1. Introduction ual targets could be misclassified (Damiani et al. this book) CoRoT has observed 26 stellar fields located in two oppo- and these numbers are mostly indicative of the overall stel- site directions for transiting planet hunting. The fields ob- lar population properties. They show however that, in a served near 6h 50m in right ascension are referred as (galac- given field, classes V and IV represent the majority of the tic) \anti-center fields”, and those near 18h 50m as \center targets. Figure III.1.2 displays how these stars classified fields”. The observing strategy consisted in staring a given as class IV and V distribute over spectral types F, G, K, star field for durations that ranged from 21 to 152 days. -

The False Positive Probability of Corot and Kepler Planetary Candidates

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 6, EPSC-DPS2011-1243, 2011 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2011 c Author(s) 2011 The False Positive probability of CoRoT and Kepler planetary candidates. R.F. Díaz (1,2), J.M. Almenara (3), A. Bonomo (3), F. Bouchy (1,2), M. Deleuil (3), G. Hébrard (1,2), C. Moutou (3) and A. Santerne (3) (1) Institut d’astrophysique de Paris, FRANCE, (2) Observatoire de Haute-Provence, FRANCE, (3) Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, FRANCE ([email protected]) Abstract tified, similarly to what is done for planet candidates detected from RV surveys, a fraction of which are in We estimate the False Positive Probability of CoRoT actuality low-mass objects in low-inclination orbits. and Kepler planetary candidates, and review critically Therefore, since the rapidly-growing number of previous results present in the literature. The ob- transiting planet candidates makes it increasingly dif- tained estimates are compared with the results from ficult to confirm each one individually by means of RV the ground-based radial velocity follow-up carried out measurements, a precise and reliable estimation of the with the HARPS and SOPHIE spectrographs for these FPP is of great importance to obtain the greatest sci- two space missions. entific return from the data acquired by CoRoT and Kepler, as well as to fully exploit the data that will be 1. Introduction obtained from future missions, like PLATO. The CoRoT and Kepler space missions are dedicated to finding transit-like events caused by extrasolar plan- 2. The False Positives ets in orbits aligned with the line of sight from Earth. -

The Giant Magellan Telescope. Status

The Giant Magellan Telescope. Status By Dr. Mauricio Pilleux Head of Administration (Chile) GMTO Corporation [email protected] April 17, 2019 Observatories in Chile: The beginnings … a successful experiment Cerro Tololo Interamerican Observatory AURA, 1962 Magellan telescopes, 2000 Las Campanas Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1968 La Silla ESO, 1969 2 Observatories in Chile: “Second stage” Very Large Telescope (VLT) Cerro Paranal, ESO, 1999 Gemini South Cerro Pachón, 2002 (AURA) ALMA NRAO-ESO-NAOJ, 2013 3 Observatories in Chile: “Stage 3.0” – big, big, big Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) Cerro Las Campanas, 2023 (GMTO Corporation) European- Extremely Large Telescope (EELT) Cerro Armazones, 2026 (ESO) Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) Cerro Pachón, 2022 (NSF/AURA-DOE/SLAC) 4 What next? Size (physical) GMT TMT EELT LSST Main Author – Presentation Title Observatories in Chile: Where? ALMA CCAT* Nanten 2 ASTE Paranal Vista ACT 2 3 E-ELT* TAO* Apex CTA* Las Campanas GMT* Polar Bear Simons Obs. La Silla 1 Tololo SOAR Gemini LSST* 6 Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT): Will be the largest in the world in 2022 25 meters in diameter “Price”: US$1340 million First light: 2023 Enclosure is 62 m high Groundbreaking research in: . Exoplanets and their atmospheres . Dark matter . Distant objects . Unknown unknowns 7 Just how tall is the GMT? 46 meters 8 Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT): The world’s largest optical telescope Korea Sao Paulo, Brazil Texas A&M Arizona New partners are welcome! Main Author – Presentation Title 9 Central mirror casting -

Orthoptera: Tristiridae), En La Zona Costera Sur De La Región De Antofagasta

Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile, 57: 133-138 (2008) REGISTRO EN ALTURA DE ENODISOMACRIS CURTIPENNIS CIGLIANO, 1989 (ORTHOPTERA: TRISTIRIDAE), EN LA ZONA COSTERA SUR DE LA REGIÓN DE ANTOFAGASTA MARIO ELGUETA¹ y CONSTANZA BARRÍA² ¹ Entomología, Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Casilla 787, Santiago, Chile; [email protected] ² Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Católica de Chile, Av. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Santiago, Chile. [email protected] RESUMEN Se documenta el hallazgo de ejemplares de Enodisomacris curtipennis Cigliano, 1989 (Tristiridae: Elasmoderini) a una altitud de 2.700 m en el Cerro Armazones en 24º34’53”S; 70º11’56”O (Datum PSAD 56) equivalente a 378.600 E y 7.280.850 S (UTM); este constituye un nuevo registro altitudinal y a la vez es la máxima altura reportada para esta especie. El Cerro Armazones forma parte de la sierra Vicuña Mackenna y se ubica al NE de la localidad costera de Paposo, a 37 km hacia el interior, en la zona sur de la Provincia de Antofagasta. Se entregan además algunos antecedentes del ambiente en que se encuentra este ortóptero. ————— Palabras clave: Tristiridae, Enodisomacris curtipennis, distribución geográfica. ABSTRACT A high altitude record for Enodisomacris curtipennis Cigliano, 1989 (Orthoptera: Tristiridae), in the Southern coastal area of Antofagasta Region. The grasshopper Enodisomacris curtipennis Cigliano, 1989 is reported for the first time at 2,700 meters of altitude in the Cerro Armazones, 24º34’53” S; 70º11’56” W (Datum PSAD 56) or 378.600 E; 7.280.850 S (UTM). This is the highest altitudinal record for this species. The hill belongs to the Vicuña Mackenna range and is located at NE of Paposo locality, in the Southern coastal area of Antofagasta Province of Chile. -

50 Years of Existence of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) 30 Years of Swiss Membership with the ESO

Federal Department for Economic Affairs, Education and Research EAER State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation SERI 50 years of existence of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) 30 years of Swiss membership with the ESO The European Southern Observatory (ESO) was founded in Paris on 5 October 1962. Exactly half a century later, on 5 October 2012, Switzerland organised a com- memoration ceremony at the University of Bern to mark ESO’s 50 years of existence and 30 years of Swiss membership with the ESO. This article provides a brief summary of the history and milestones of Swiss member- ship with the ESO as well as an overview of the most important achievements and challenges. Switzerland’s route to ESO membership Nearly twenty years after the ESO was founded, the time was ripe for Switzerland to apply for membership with the ESO. The driving forces on the academic side included the Universi- ty of Geneva and the University of Basel, which wanted to gain access to the most advanced astronomical research available. In 1980, the Federal Council submitted its Dispatch on Swiss membership with the ESO to the Federal Assembly. In 1981, the Federal Assembly adopted a federal decree endorsing Swiss membership with the ESO. In 1982, the Swiss Confederation filed the official documents for ESO membership in Paris. In 1982, Switzerland paid the initial membership fee and, in 1983, the first year’s member- ship contributions. High points of Swiss participation In 1987, the Federal Council issued a federal decree on Swiss participation in the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) to be built at the Paranal Observatory in the Chilean Atacama Desert. -

The Trilogy Is Complete -- Gigagalaxy Zoom Phase 3 28 September 2009

The trilogy is complete -- GigaGalaxy Zoom Phase 3 28 September 2009 "globules" and the most prominent ones have been catalogued by the astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard. The Lagoon Nebula hosts the young open stellar cluster known as NGC 6530. This is home for 50 to 100 stars and twinkles in the lower left portion of the nebula. Observations suggest that the cluster is slightly in front of the nebula itself, though still enshrouded by dust, as revealed by reddening of the starlight, an effect that occurs when small dust particles scatter light. The third image of ESO's GigaGalaxy Zoom project is an amazing vista of the Lagoon Nebula taken with the 67-million-pixel Wide Field Imager attached to the MPG/ESO 2.2-meter telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. The image covers more than one and a half square degree -- an area eight times larger than that of the Full Moon -- with a total of about 370 million pixels. It is based on images acquired using three different broadband filters (B, V, R) and one narrow- band filter (H-alpha). Credit: ESO The newly released image extends across a field of view of more than one and a half square degree — an area eight times larger than that of the full Moon — and was obtained with the Wide Field Imager attached to the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. This 67-million-pixel camera has already created several of ESO's iconic pictures. The intriguing object depicted here — the Lagoon Nebula — is located four to five thousand light- years away towards the constellation of Sagittarius The three images of ESO’s GigaGalaxy Zoom project (the Archer). -

HATS-3B: an Inflated Hot Jupiter Transiting an F-Type Star

Draft version January 5, 2018 A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 HATS-3b: AN INFLATED HOT JUPITER TRANSITING AN F-TYPE STAR D. Bayliss1, G. Zhou1, K. Penev2,3, G. A.´ Bakos2,3,⋆,⋆⋆, J. D. Hartman2,3, A. Jordan´ 4, L. Mancini5, M. Mohler5, V. Suc4, M. Rabus4, B. Beky´ 3, Z. Csubry2,3, L. Buchhave6, T. Henning5, N. Nikolov5, B. Csak´ 5, R. Brahm4, N. Espinoza4, R. W. Noyes3, B. Schmidt1, P. Conroy1, D. J. Wright,7,8, C. G. Tinney,7,8, B. C. Addison,7,8, P. D. Sackett,1, D. D. Sasselov3, J. Laz´ ar´ 9, I. Papp9, P. Sari´ 9 Draft version January 5, 2018 ABSTRACT We report the discovery by the HATSouth survey of HATS-3b, a transiting extrasolar planet orbiting a V=12.4 F dwarf star. HATS-3b has a period of P =3.5479d, mass of Mp =1.07 MJ, and radius of Rp =1.38 RJ. Given the radius of the planet, the brightness of the host star, and the stellar rotational 1 velocity (v sin i = 9.0kms− ), this system will make an interesting target for future observations to measure the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect and determine its spin-orbit alignment. We detail the low/medium-resolution reconnaissance spectroscopy that we are now using to deal with large numbers of transiting planet candidates produced by the HATSouth survey. We show that this important step in discovering planets produces log g and Teff parameters at a precision suitable for efficient candidate vetting, as well as efficiently identifying stellar mass eclipsing binaries with radial velocity 1 semi-amplitudes as low as 1 km s− . -

Exoplanet Community Report

JPL Publication 09‐3 Exoplanet Community Report Edited by: P. R. Lawson, W. A. Traub and S. C. Unwin National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California March 2009 The work described in this publication was performed at a number of organizations, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Publication was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Compiling and publication support was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under a contract with NASA. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement by the United States Government, or the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. © 2009. All rights reserved. The exoplanet community’s top priority is that a line of probeclass missions for exoplanets be established, leading to a flagship mission at the earliest opportunity. iii Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................1 1.2 EXOPLANET FORUM 2008: THE PROCESS OF CONSENSUS BEGINS.....................................................2 -

Search for Wide Substellar Companions to Young Nearby Stars with the VISTA Hemisphere Survey

Highlights on Spanish Astrophysics X, Proceedings of the XIII Scientific Meeting of the Spanish Astronomical Society held on July 16 – 20, 2018, in Salamanca, Spain. B. Montesinos, A. Asensio Ramos, F. Buitrago, R. Schödel, E. Villaver, S. Pérez-Hoyos, I. Ordóñez-Etxeberria (eds.), 2019 Search for wide substellar companions to young nearby stars with the VISTA Hemisphere Survey. P. Chinchilla1;2, V.J.S. B´ejar1;2, N. Lodieu1;2, M.R. Zapatero Osorio3, B. Gauza4, R. Rebolo1;2;5, and A. P´erezGarrido6 1 Instituto de Astrof´ısicade Canarias (IAC), c/V´ıaL´acteaS/N, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 2 Dpto. de Astrof´ısica,Universidad de La Laguna (ULL), 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3 Centro de Astrobiolog´ıa(CSIC-INTA), Ctra. de Ajalvir km 4, 28850 Torrej´onde Ardoz, Madrid, Spain 4 Dpto. de Astronom´ıa,Universidad de Chile, Camino el Observatorio 1515, Casilla 36-D, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile 5 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas(CSIC), Spain 6 Dpto. de F´ısicaAplicada, Universidad Polit´ecnicade Cartagena, 30202 Cartagena, Murcia, Spain Abstract We have performed a search for substellar objects as common proper motion companions to young nearby stars (including members of the Young Moving Groups AB Doradus, TW Hydrae, Tucana-Horologium and Beta Pictoris, and the Upper Scorpius young association) up to separations of 50,000 AU, using the VISTA Hemisphere Survey and 2MASS astro- metric and photometric data. We have found tens of candidates with spectral types from M to L, and estimated masses from low-mass stars to the deuterium-burning limit mass. -

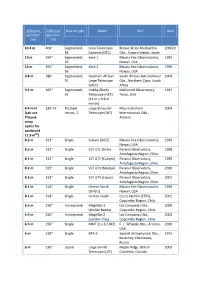

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

The Case for Irish Membership of the European Southern Observatory Prepared by the Institute of Physics in Ireland June 2014

The Case for Irish Membership of the European Southern Observatory Prepared by the Institute of Physics in Ireland June 2014 The Case for Irish Membership of the European Southern Observatory Contents Summary 2 European Southern Observatory Overview 3 European Extremely Large Telescope 5 Summary of ESO Telescopes and Instrumentation 6 Technology Development at ESO 7 Big Data and Energy-Efficient Computing 8 Return to Industry 9 Ireland and Space Technologies 10 Astrophysics and Ireland 13 Undergraduate Teaching 15 Outreach and Astronomy 17 Education and Training 19 ESO Membership Fee 20 Conclusions 22 References 24 1 Summary The European Southern Observatory (ESO) is universally acknowledged as being the world leading facility for observational astronomy. The astrophysics community in Ireland is united in calling for Irish membership of ESO believing that this action would strongly support the Irish government’s commitment to its STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) agenda. An essential element of the government’s plans for the Irish economy is to substantially grow its high-tech business sector. Physics is a core part of that base, with 86,000 jobs in Ireland in this sector1 while astrophysics, in particular, is a key driver both of science interest and especially of innovation. To support this agenda, Irish scientists and engineers need access to the best research facilities and with this access comes the benefits of spin-off technology, contracts and the jobs which this can bring. ESO is currently expanding its membership to include Brazil and is considering some eastern European countries. The cost of membership will increase as more states join and as Ireland’s GDP increases.