The Limiting Equations of Nonautonomous Ordinary Differential Equations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limits Involving Infinity (Horizontal and Vertical Asymptotes Revisited)

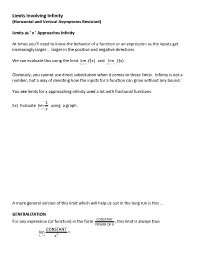

Limits Involving Infinity (Horizontal and Vertical Asymptotes Revisited) Limits as ‘ x ’ Approaches Infinity At times you’ll need to know the behavior of a function or an expression as the inputs get increasingly larger … larger in the positive and negative directions. We can evaluate this using the limit limf ( x ) and limf ( x ) . x→ ∞ x→ −∞ Obviously, you cannot use direct substitution when it comes to these limits. Infinity is not a number, but a way of denoting how the inputs for a function can grow without any bound. You see limits for x approaching infinity used a lot with fractional functions. 1 Ex) Evaluate lim using a graph. x→ ∞ x A more general version of this limit which will help us out in the long run is this … GENERALIZATION For any expression (or function) in the form CONSTANT , this limit is always true POWER OF X CONSTANT lim = x→ ∞ xn HOW TO EVALUATE A LIMIT AT INFINITY FOR A RATIONAL FUNCTION Step 1: Take the highest power of x in the function’s denominator and divide each term of the fraction by this x power. Step 2: Apply the limit to each term in both numerator and denominator and remember: n limC / x = 0 and lim C= C where ‘C’ is a constant. x→ ∞ x→ ∞ Step 3: Carefully analyze the results to see if the answer is either a finite number or ‘ ∞ ’ or ‘ − ∞ ’ 6x − 3 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . x→ ∞ 5+ 2 x 3− 2x − 5 x 2 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . x→ ∞ 2x + 7 5x+ 2 x −2 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . -

Section 8.8: Improper Integrals

Section 8.8: Improper Integrals One of the main applications of integrals is to compute the areas under curves, as you know. A geometric question. But there are some geometric questions which we do not yet know how to do by calculus, even though they appear to have the same form. Consider the curve y = 1=x2. We can ask, what is the area of the region under the curve and right of the line x = 1? We have no reason to believe this area is finite, but let's ask. Now no integral will compute this{we have to integrate over a bounded interval. Nonetheless, we don't want to throw up our hands. So note that b 2 b Z (1=x )dx = ( 1=x) 1 = 1 1=b: 1 − j − In other words, as b gets larger and larger, the area under the curve and above [1; b] gets larger and larger; but note that it gets closer and closer to 1. Thus, our intuition tells us that the area of the region we're interested in is exactly 1. More formally: lim 1 1=b = 1: b − !1 We can rewrite that as b 2 lim Z (1=x )dx: b !1 1 Indeed, in general, if we want to compute the area under y = f(x) and right of the line x = a, we are computing b lim Z f(x)dx: b !1 a ASK: Does this limit always exist? Give some situations where it does not exist. They'll give something that blows up. -

13 Limits and the Foundations of Calculus

13 Limits and the Foundations of Calculus We have· developed some of the basic theorems in calculus without reference to limits. However limits are very important in mathematics and cannot be ignored. They are crucial for topics such as infmite series, improper integrals, and multi variable calculus. In this last section we shall prove that our approach to calculus is equivalent to the usual approach via limits. (The going will be easier if you review the basic properties of limits from your standard calculus text, but we shall neither prove nor use the limit theorems.) Limits and Continuity Let {be a function defined on some open interval containing xo, except possibly at Xo itself, and let 1 be a real number. There are two defmitions of the· state ment lim{(x) = 1 x-+xo Condition 1 1. Given any number CI < l, there is an interval (al> b l ) containing Xo such that CI <{(x) ifal <x < b i and x ;6xo. 2. Given any number Cz > I, there is an interval (a2, b2) containing Xo such that Cz > [(x) ifa2 <x< b 2 and x :;Cxo. Condition 2 Given any positive number €, there is a positive number 0 such that If(x) -11 < € whenever Ix - x 0 I< 5 and x ;6 x o. Depending upon circumstances, one or the other of these conditions may be easier to use. The following theorem shows that they are interchangeable, so either one can be used as the defmition oflim {(x) = l. X--->Xo 180 LIMITS AND CONTINUITY 181 Theorem 1 For any given f. -

Two Fundamental Theorems About the Definite Integral

Two Fundamental Theorems about the Definite Integral These lecture notes develop the theorem Stewart calls The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in section 5.3. The approach I use is slightly different than that used by Stewart, but is based on the same fundamental ideas. 1 The definite integral Recall that the expression b f(x) dx ∫a is called the definite integral of f(x) over the interval [a,b] and stands for the area underneath the curve y = f(x) over the interval [a,b] (with the understanding that areas above the x-axis are considered positive and the areas beneath the axis are considered negative). In today's lecture I am going to prove an important connection between the definite integral and the derivative and use that connection to compute the definite integral. The result that I am eventually going to prove sits at the end of a chain of earlier definitions and intermediate results. 2 Some important facts about continuous functions The first intermediate result we are going to have to prove along the way depends on some definitions and theorems concerning continuous functions. Here are those definitions and theorems. The definition of continuity A function f(x) is continuous at a point x = a if the following hold 1. f(a) exists 2. lim f(x) exists xœa 3. lim f(x) = f(a) xœa 1 A function f(x) is continuous in an interval [a,b] if it is continuous at every point in that interval. The extreme value theorem Let f(x) be a continuous function in an interval [a,b]. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative

1 Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative: A function F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I if for all x in I. Representation of Antiderivatives: If F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I, then G is an antiderivative of f on the interval I if and only if G is of the form G(x) = F(x) + C, for all x in I where C is a constant. Sigma Notation: The sum of n terms a1,a2,a3,…,an is written as where I is the index of summation, ai is the ith term of the sum, and the upper and lower bounds of summation are n and 1. Summation Formulas: 1. 2. 3. 4. Limits of the Lower and Upper Sums: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The limits as n of both the lower and upper sums exist and are equal to each other. That is, where are the minimum and maximum values of f on the subinterval. Definition of the Area of a Region in the Plane: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The area if a region bounded by the graph of f, the x-axis and the vertical lines x=a and x=b is Area = where . Definition of a Riemann Sum: Let f be defined on the closed interval [a,b], and let be a partition of [a,b] given by a =x0<x1<x2<…<xn-1<xn=b where xi is the width of the ith subinterval. -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

Math 220 GW 7 SOLUTIONS 1. Using the Limit Definition of Derivative, Find the Derivative Function, F (X), of the Following Funct

Math 220 GW 7 SOLUTIONS 1. Using the limit definition of derivative, find the derivative function, f 0(x), of the following functions. Show all your beautiful algebra. (a) f(x) = 2x f(x + h) − f(x) 2(x + h) − 2x lim = lim h!0 h h!0 h 2x + 2h − 2x = lim h!0 h 2h = lim h!0 h 2: (b) f(x) = −x2 + 2x f(x + h) − f(x) −(x + h)2 + 2(x + h) + x2 − 2x lim = lim h!0 h h!0 h −x2 − 2xh − h2 + 2x + 2h + x2 − 2x = lim h!0 h −2xh − h2 + 2h = lim h!0 h = lim(−2x − h + 2) h!0 = −2x + 2: 1 2. You are told f(x) = 2x3 − 4x, and f 0(x) = 6x2 − 4. Find f 0(3) and f 0(−1) and explain, in words, how to interpret these numbers. f 0(3) = 6(3)2 − 4 = 50: f 0(1) = 6(1)2 − 4 = 2: These are the slopes of f(x) at x = 3 and x = 1. Both are positive, thus f is increasing at those points. Also, 50 > 2, so f is increasing faster at x = 3 than at x = 1. Example Find the derivative of f(x) = 3=x2. f(x + h) − f(x) f 0(x) = lim h!0 h 3 3 2 − 2 = lim (x+h) x h!0 h x2 3 3 (x+h)2 2 ∗ 2 − 2 ∗ 2 = lim x (x+h) x (x+h) h!0 h 3x2−3(x+h)2 2 2 = lim x (x+h) h!0 h 1 3x2 − 3(x + h)2 1 = lim ∗ h!0 x2(x + h)2 h 3x2 − 3(x2 + 2xh + h2) = lim h!0 hx2(x + h)2 3x2 − 3x2 − 6xh + h2 = lim h!0 hx2(x + h)2 h(−6x + h) = lim h!0 hx2(x + h)2 h −6x + h = lim ∗ h!0 h x2(x + h)2 −6x + h = lim h!0 x2(x + h)2 −6x + 0 = x2(x + 0)2 −6x = x4 −6 = x3 3. -

Math Handbook of Formulas, Processes and Tricks Calculus

Math Handbook of Formulas, Processes and Tricks (www.mathguy.us) Calculus Prepared by: Earl L. Whitney, FSA, MAAA Version 4.9 February 24, 2021 Copyright 2008‐21, Earl Whitney, Reno NV. All Rights Reserved Note to Students This Calculus Handbook was developed primarily through work with a number of AP Calculus classes, so it contains what most students need to prepare for the AP Calculus Exam (AB or BC) or a first‐year college Calculus course. In addition, a number of more advanced topics have been added to the handbook to whet the student’s appetite for higher level study. It is important to note that some of the tips and tricks noted in this handbook, while generating valid solutions, may not be acceptable to the College Board or to the student’s instructor. The student should always check with their instructor to determine if a particular technique that they find useful is acceptable. Why Make this Handbook? One of my main purposes for writing this handbook is to encourage the student to wonder, to ask “what about … ?” or “what if … ?” I find that students are so busy today that they don’t have the time, or don’t take the time, to find the beauty and majesty that exists within Mathematics. And, it is there, just below the surface. So be curious and seek it out. The answers to all of the questions below are inside this handbook, but are seldom taught. What is oscillating behavior and how does it affect a limit? Is there a generalized rule for the derivative of a product of multiple functions? What’s the partial derivative shortcut to implicit differentiation? What are the hyperbolic functions and how do they relate to the trigonometric functions? When can I simplify a difficult definite integral by breaking it into its even and odd components? What is Vector Calculus? Additionally, ask yourself: Why … ? Always ask “why?” Can I come up with a simpler method of doing things than I am being taught? What problems can I come up with to stump my friends? Those who approach math in this manner will be tomorrow’s leaders. -

The Definite Integral

Mathematics Learning Centre Introduction to Integration Part 2: The Definite Integral Mary Barnes c 1999 University of Sydney Contents 1Introduction 1 1.1 Objectives . ................................. 1 2 Finding Areas 2 3 Areas Under Curves 4 3.1 What is the point of all this? ......................... 6 3.2 Note about summation notation ........................ 6 4 The Definition of the Definite Integral 7 4.1 Notes . ..................................... 7 5 The Fundamental Theorem of the Calculus 8 6 Properties of the Definite Integral 12 7 Some Common Misunderstandings 14 7.1 Arbitrary constants . ............................. 14 7.2 Dummy variables . ............................. 14 8 Another Look at Areas 15 9 The Area Between Two Curves 19 10 Other Applications of the Definite Integral 21 11 Solutions to Exercises 23 Mathematics Learning Centre, University of Sydney 1 1Introduction This unit deals with the definite integral.Itexplains how it is defined, how it is calculated and some of the ways in which it is used. We shall assume that you are already familiar with the process of finding indefinite inte- grals or primitive functions (sometimes called anti-differentiation) and are able to ‘anti- differentiate’ a range of elementary functions. If you are not, you should work through Introduction to Integration Part I: Anti-Differentiation, and make sure you have mastered the ideas in it before you begin work on this unit. 1.1 Objectives By the time you have worked through this unit you should: • Be familiar with the definition of the definite integral as the limit of a sum; • Understand the rule for calculating definite integrals; • Know the statement of the Fundamental Theorem of the Calculus and understand what it means; • Be able to use definite integrals to find areas such as the area between a curve and the x-axis and the area between two curves; • Understand that definite integrals can also be used in other situations where the quantity required can be expressed as the limit of a sum. -

A Document with an Image

1 Limits at Infinity and Infinite Limits c 2002 Donald Kreider and Dwight Lahr It may be argued that the notion of limit is the most fundamental in calculus— indeed, calculus begins with the study of functions and limits. In many respects it is an intuitive concept. The idea of one object “approaching” another, even approaching it “arbitrarily closely” seems natural enough. Our language is full of words that express exactly such actions. And in mathematics the idea of the value of x approaching some real number L, and coming as close to it as we please, does not seem to be stretching the ideas of everyday speech. It is surprising, then, that there are such subtle consequences of the concept of limit and that it took literally thousands of years to “get it right”. In the definition of limx→a f(x), a is a real number. It would be natural to relax this to include the cases x → ∞ and x → −∞. This means that the value of x increases beyond all bounds that you might name (x → ∞) or decreases below all (negative) bounds that you might name. Definition 1: limx→∞ f(x) = L means that the value of f(x) approaches L as the value of x approaches +∞. This means that f(x) can be made as close to L as we please by taking the value of x sufficiently large. Similarly, limx→−∞ f(x) = L means that f(x) can be made as close to L as we please by taking the value of x sufficiently small (in the negative direction). -

Ordinary Differential Equations Simon Brendle

Ordinary Differential Equations Simon Brendle Contents Preface vii Chapter 1. Introduction 1 x1.1. Linear ordinary differential equations and the method of integrating factors 1 x1.2. The method of separation of variables 3 x1.3. Problems 4 Chapter 2. Systems of linear differential equations 5 x2.1. The exponential of a matrix 5 x2.2. Calculating the matrix exponential of a diagonalizable matrix 7 x2.3. Generalized eigenspaces and the L + N decomposition 10 x2.4. Calculating the exponential of a general n × n matrix 15 x2.5. Solving systems of linear differential equations using matrix exponentials 17 x2.6. Asymptotic behavior of solutions 21 x2.7. Problems 24 Chapter 3. Nonlinear systems 27 x3.1. Peano's existence theorem 27 x3.2. Existence theory via the method of Picard iterates 30 x3.3. Uniqueness and the maximal time interval of existence 32 x3.4. Continuous dependence on the initial data 34 x3.5. Differentiability of flows and the linearized equation 37 x3.6. Liouville's theorem 39 v vi Contents x3.7. Problems 40 Chapter 4. Analysis of equilibrium points 43 x4.1. Stability of equilibrium points 43 x4.2. The stable manifold theorem 44 x4.3. Lyapunov's theorems 53 x4.4. Gradient and Hamiltonian systems 55 x4.5. Problems 56 Chapter 5. Limit sets of dynamical systems and the Poincar´e- Bendixson theorem 57 x5.1. Positively invariant sets 57 x5.2. The !-limit set of a trajectory 60 x5.3. !-limit sets of planar dynamical systems 62 x5.4. Stability of periodic solutions and the Poincar´emap 65 x5.5.