Introduction to Programming Languages and Syntax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layout-Sensitive Generalized Parsing

Layout-sensitive Generalized Parsing Sebastian Erdweg, Tillmann Rendel, Christian K¨astner,and Klaus Ostermann University of Marburg, Germany Abstract. The theory of context-free languages is well-understood and context-free parsers can be used as off-the-shelf tools in practice. In par- ticular, to use a context-free parser framework, a user does not need to understand its internals but can specify a language declaratively as a grammar. However, many languages in practice are not context-free. One particularly important class of such languages is layout-sensitive languages, in which the structure of code depends on indentation and whitespace. For example, Python, Haskell, F#, and Markdown use in- dentation instead of curly braces to determine the block structure of code. Their parsers (and lexers) are not declaratively specified but hand-tuned to account for layout-sensitivity. To support declarative specifications of layout-sensitive languages, we propose a parsing framework in which a user can annotate layout in a grammar. Annotations take the form of constraints on the relative posi- tioning of tokens in the parsed subtrees. For example, a user can declare that a block consists of statements that all start on the same column. We have integrated layout constraints into SDF and implemented a layout- sensitive generalized parser as an extension of generalized LR parsing. We evaluate the correctness and performance of our parser by parsing 33 290 open-source Haskell files. Layout-sensitive generalized parsing is easy to use, and its performance overhead compared to layout-insensitive parsing is small enough for practical application. 1 Introduction Most computer languages prescribe a textual syntax. -

Parse Forest Diagnostics with Dr. Ambiguity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CWI's Institutional Repository Parse Forest Diagnostics with Dr. Ambiguity H. J. S. Basten and J. J. Vinju Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI) Science Park 123, 1098 XG Amsterdam, The Netherlands {Jurgen.Vinju,Bas.Basten}@cwi.nl Abstract In this paper we propose and evaluate a method for locating causes of ambiguity in context-free grammars by automatic analysis of parse forests. A parse forest is the set of parse trees of an ambiguous sentence. Deducing causes of ambiguity from observing parse forests is hard for grammar engineers because of (a) the size of the parse forests, (b) the complex shape of parse forests, and (c) the diversity of causes of ambiguity. We first analyze the diversity of ambiguities in grammars for programming lan- guages and the diversity of solutions to these ambiguities. Then we introduce DR.AMBIGUITY: a parse forest diagnostics tools that explains the causes of ambiguity by analyzing differences between parse trees and proposes solutions. We demonstrate its effectiveness using a small experiment with a grammar for Java 5. 1 Introduction This work is motivated by the use of parsers generated from general context-free gram- mars (CFGs). General parsing algorithms such as GLR and derivates [35,9,3,6,17], GLL [34,22], and Earley [16,32] support parser generation for highly non-deterministic context-free grammars. The advantages of constructing parsers using such technology are that grammars may be modular and that real programming languages (often requiring parser non-determinism) can be dealt with efficiently1. -

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: the Power of Dynamic Analysis

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: The Power of Dynamic Analysis Terence Parr Sam Harwell Kathleen Fisher University of San Francisco University of Texas at Austin Tufts University [email protected] [email protected] kfi[email protected] Abstract PEGs are unambiguous by definition but have a quirk where Despite the advances made by modern parsing strategies such rule A ! a j ab (meaning “A matches either a or ab”) can never as PEG, LL(*), GLR, and GLL, parsing is not a solved prob- match ab since PEGs choose the first alternative that matches lem. Existing approaches suffer from a number of weaknesses, a prefix of the remaining input. Nested backtracking makes de- including difficulties supporting side-effecting embedded ac- bugging PEGs difficult. tions, slow and/or unpredictable performance, and counter- Second, side-effecting programmer-supplied actions (muta- intuitive matching strategies. This paper introduces the ALL(*) tors) like print statements should be avoided in any strategy that parsing strategy that combines the simplicity, efficiency, and continuously speculates (PEG) or supports multiple interpreta- predictability of conventional top-down LL(k) parsers with the tions of the input (GLL and GLR) because such actions may power of a GLR-like mechanism to make parsing decisions. never really take place [17]. (Though DParser [24] supports The critical innovation is to move grammar analysis to parse- “final” actions when the programmer is certain a reduction is time, which lets ALL(*) handle any non-left-recursive context- part of an unambiguous final parse.) Without side effects, ac- free grammar. ALL(*) is O(n4) in theory but consistently per- tions must buffer data for all interpretations in immutable data forms linearly on grammars used in practice, outperforming structures or provide undo actions. -

Formal Languages - 3

Formal Languages - 3 • Ambiguity in PLs – Problems with if-then-else constructs – Harder problems • Chomsky hierarchy for formal languages – Regular and context-free languages – Type 1: Context-sensitive languages – Type 0 languages and Turing machines Formal Languages-3, CS314 Fall 01© BGRyder 1 Dangling Else Ambiguity (Pascal) Start ::= Stmt Stmt ::= Ifstmt | Astmt Ifstmt ::= IF LogExp THEN Stmt | IF LogExp THEN Stmt ELSE Stmt Astmt ::= Id := Digit Digit ::= 0|1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9 LogExp::= Id = 0 Id ::= a|b|c|d|e|f|g|h|i|j|k|l|m|n|o|p|q|r|s|t|u|v|w|x|y|z How are compound if statements parsed using this grammar?? Formal Languages-3, CS314 Fall 01© BGRyder 2 1 IF x = 0 THEN IF y = 0 THEN z := 1 ELSE w := 2; Start Parse Tree 1 Stmt Ifstmt IF LogExp THEN Stmt Ifstmt Id = 0 IF LogExp THEN Stmt ELSE Stmt x Id = 0 Astmt Astmt Id := Digit y Id := Digit z 1 w 2 Formal Languages-3, CS314 Fall 01© BGRyder 3 IF x = 0 THEN IF y = 0 THEN z := 1 ELSE w := 2; Start Stmt Parse Tree 2 Ifstmt Q: which tree is correct? IF LogExp THEN Stmt ELSE Stmt Id = 0 Ifstmt Astmt IF LogExp THEN Stmt x Id := Digit Astmt Id = 0 w 2 Id := Digit y z 1 Formal Languages-3, CS314 Fall 01© BGRyder 4 2 How Solve the Dangling Else? • Algol60: use block structure if x = 0 then begin if y = 0 then z := 1 end else w := 2 • Algol68: use statement begin/end markers if x = 0 then if y = 0 then z := 1 fi else w := 2 fi • Pascal: change the if statement grammar to disallow parse tree 2; that is, always associate an else with the closest if Formal Languages-3, CS314 Fall 01© BGRyder 5 New Pascal Grammar Start ::= Stmt Stmt ::= Stmt1 | Stmt2 Stmt1 ::= IF LogExp THEN Stmt1 ELSE Stmt1 | Astmt Stmt2 ::= IF LogExp THEN Stmt | IF LogExp THEN Stmt1 ELSE Stmt2 Astmt ::= Id := Digit Digit ::= 0|1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9 LogExp::= Id = 0 Id ::= a|b|c|d|e|f|g|h|i|j|k|l|m|n|o|p|q|r|s|t|u|v|w|x|y|z Note: only if statements with IF..THEN..ELSE are allowed after the THEN clause of an IF-THEN-ELSE statement. -

Ordered Sets in the Calculus of Data Structures

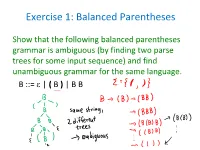

Exercise 1: Balanced Parentheses Show that the following balanced parentheses grammar is ambiguous (by finding two parse trees for some input sequence) and find unambiguous grammar for the same language. B ::= | ( B ) | B B Remark • The same parse tree can be derived using two different derivations, e.g. B -> (B) -> (BB) -> ((B)B) -> ((B)) -> (()) B -> (B) -> (BB) -> ((B)B) -> (()B) -> (()) this correspond to different orders in which nodes in the tree are expanded • Ambiguity refers to the fact that there are actually multiple parse trees, not just multiple derivations. Towards Solution • (Note that we must preserve precisely the set of strings that can be derived) • This grammar: B ::= | A A ::= ( ) | A A | (A) solves the problem with multiple symbols generating different trees, but it is still ambiguous: string ( ) ( ) ( ) has two different parse trees Solution • Proposed solution: B ::= | B (B) • this is very smart! How to come up with it? • Clearly, rule B::= B B generates any sequence of B's. We can also encode it like this: B ::= C* C ::= (B) • Now we express sequence using recursive rule that does not create ambiguity: B ::= | C B C ::= (B) • but now, look, we "inline" C back into the rules for so we get exactly the rule B ::= | B (B) This grammar is not ambiguous and is the solution. We did not prove this fact (we only tried to find ambiguous trees but did not find any). Exercise 2: Dangling Else The dangling-else problem happens when the conditional statements are parsed using the following grammar. S ::= S ; S S ::= id := E S ::= if E then S S ::= if E then S else S Find an unambiguous grammar that accepts the same conditional statements and matches the else statement with the nearest unmatched if. -

14 a Simple Compiler - the Front End

Compilers and Compiler Generators © P.D. Terry, 2000 14 A SIMPLE COMPILER - THE FRONT END At this point it may be of interest to consider the construction of a compiler for a simple programming language, specifically that of section 8.7. In a text of this nature it is impossible to discuss a full-blown compiler, and the value of our treatment may arguably be reduced by the fact that in dealing with toy languages and toy compilers we shall be evading some of the real issues that a compiler writer has to face. However, we hope the reader will find the ensuing discussion of interest, and that it will serve as a useful preparation for the study of much larger compilers. The technique we shall follow is one of slow refinement, supplementing the discussion with numerous asides on the issues that would be raised in compiling larger languages. Clearly, we could opt to develop a completely hand-crafted compiler, or simply to use a tool like Coco/R. We shall discuss both approaches. Even when a compiler is constructed by hand, having an attributed grammar to describe it is very worthwhile. On the source diskette can be found a great deal of code, illustrating different stages of development of our system. Although some of this code is listed in appendices, its volume precludes printing all of it. Some of it has deliberately been written in a way that allows for simple modification when attempting the exercises, and is thus not really of "production quality". For example, in order to allow components such as the symbol table handler and code generator to be used either with hand-crafted or with Coco/R generated systems, some compromises in design have been necessary. -

Disambiguation Filters for Scannerless Generalized LR Parsers

Disambiguation Filters for Scannerless Generalized LR Parsers Mark G. J. van den Brand1,4, Jeroen Scheerder2, Jurgen J. Vinju1, and Eelco Visser3 1 Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica (CWI) Kruislaan 413, 1098 SJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands {Mark.van.den.Brand,Jurgen.Vinju}@cwi.nl 2 Department of Philosophy, Utrecht University Heidelberglaan 8, 3584 CS Utrecht, The Netherlands [email protected] 3 Institute of Information and Computing Sciences, Utrecht University P.O. Box 80089, 3508TB Utrecht, The Netherlands [email protected] 4 LORIA-INRIA 615 rue du Jardin Botanique, BP 101, F-54602 Villers-l`es-Nancy Cedex, France Abstract. In this paper we present the fusion of generalized LR pars- ing and scannerless parsing. This combination supports syntax defini- tions in which all aspects (lexical and context-free) of the syntax of a language are defined explicitly in one formalism. Furthermore, there are no restrictions on the class of grammars, thus allowing a natural syntax tree structure. Ambiguities that arise through the use of unrestricted grammars are handled by explicit disambiguation constructs, instead of implicit defaults that are taken by traditional scanner and parser gener- ators. Hence, a syntax definition becomes a full declarative description of a language. Scannerless generalized LR parsing is a viable technique that has been applied in various industrial and academic projects. 1 Introduction Since the introduction of efficient deterministic parsing techniques, parsing is considered a closed topic for research, both by computer scientists and by practi- cioners in compiler construction. Tools based on deterministic parsing algorithms such as LEX & YACC [15,11] (LALR) and JavaCC (recursive descent), are con- sidered adequate for dealing with almost all modern (programming) languages. -

CS4200 | Compiler Construction | September 10, 2020 Disambiguation and Layout-Sensitive Syntax

Disambiguation and Layout-Sensitive Syntax Eelco Visser CS4200 | Compiler Construction | September 10, 2020 Disambiguation and Layout-Sensitive Syntax Syntax Definition Summary Derivations - Generating sentences and trees from context-free grammars Ambiguity Declarative Disambiguation Rules - Associativity and priority Grammar Transformations - Eliminating ambiguity by transformation Layout-Sensitive Syntax - Disambiguation using layout constraints Structure Syntax = Structure module structure let inc = function(x) { x + 1 } imports Common in inc(3) context-free start-symbols Exp end context-free syntax Exp.Var = ID Exp.Int = INT Exp.Add = Exp "+" Exp Let( Exp.Fun = "function" "(" {ID ","}* ")" "{" Exp "}" [ Bnd( "inc" Exp.App = Exp "(" {Exp ","}* ")" , Fun(["x"], Add(Var("x"), Int("1"))) ) Exp.Let = "let" Bnd* "in" Exp "end" ] , App(Var("inc"), [Int("3")]) Bnd.Bnd = ID "=" Exp ) Token = Character module structure let inc = function(x) { x + 1 } imports Common in inc(3) context-free start-symbols Exp end context-free syntax Exp.Var = ID module Common Exp.Int = INT lexical syntax Exp.Add = Exp "+" Exp ID = [a-zA-Z] [a-zA-Z0-9]* Exp.Fun = "function" "(" {ID ","}* ")" "{" Exp "}" INT = [\-]? [0-9]+ Exp.App = Exp "(" {Exp ","}* ")" Exp.Let = "let" Bnd* "in" Exp "end" Lexical Syntax = Context-Free Syntax Bnd.Bnd = ID "=" Exp (But we don’t care about structure of lexical syntax) Literal = Non-Terminal module structure let inc = function(x) { x + 1 } imports Common in inc(3) context-free start-symbols Exp end context-free syntax syntax Exp.Var -

Programming Languages

Programming Languages CSCI-GA.2110-001 Summer 2011 Dr. Cory Plock What this course is ■ A study of programming language paradigms ◆ Imperitive ◆ Functional ◆ Logical ◆ Object-oriented ■ Tour of programming language history & roots. ■ Introduction to core language design & implementation concepts. ■ Exposure to new languages you may not have used before. ■ Ability to reason about language benefits/pitfalls. ■ A look at programming language implementation. ■ Offers an appreciation of language standards. ■ Provides the ability to more quickly learn new languages. 2 / 26 What this course isn’t ■ A comprehensive study of one or more languages. ■ An exercise in learning as many languages as possible. ■ A software engineering course. ■ A compiler course. 3 / 26 Introduction The main themes of programming language design and use: ■ Paradigm (Model of computation) ■ Expressiveness ◆ control structures ◆ abstraction mechanisms ◆ types and their operations ◆ tools for programming in the large ■ Ease of use: Writeability / Readability / Maintainability 4 / 26 Language as a tool for thought ■ Role of language as a communication vehicle among programmers can be just as important as ease of writing ■ All general-purpose languages are Turing complete (They can compute the same things) ■ But languages can make expression of certain algorithms difficult or easy. ◆ Try multiplying two Roman numerals ■ Idioms in language A may be useful inspiration when writing in language B. 5 / 26 Idioms ■ Copying a string q to p in C: while (*p++ = *q++) ; ■ Removing duplicates -

A Practical Tutorial on Context Free Grammars

A Practical Tutorial on Context Free Grammars Robert B. Heckendorn University of Idaho September 16, 2020 Contents 1 Some Definitions 3 2 Some Common Idioms and Hierarchical Development 5 2.1 A grammar for a language that allows a list of X's . .5 2.2 A Language that is a List of X's or Y's . .5 2.3 A Language that is a List of X's Terminated with a Semicolon . .5 2.4 Hierarchical Complexification . .6 2.5 A Language Where There are not Terminal Semicolons but Separating Commas . .6 2.6 A language where each X is followed by a terminating semicolon: . .6 2.7 An arg list of X's, Y's and Z's: . .6 2.8 A Simple Type Declaration: . .6 2.9 Augment the Type Grammar with the Keyword Static . .7 2.10 A Tree Structure as Nested Parentheses . .7 3 Associativity and Precedence 7 3.1 A Grammar for an Arithmetic Expression . .7 3.2 Grouping with Parentheses . .8 3.3 Unary operators . .9 3.4 An Example Problem . 10 4 How can Things go Wrong 10 4.1 Inescapable Productions . 10 4.2 Ambiguity . 11 4.2.1 Ambiguity by Ill-specified Associativity . 12 4.2.2 Ambiguity by Infinite Loop . 13 4.2.3 Ambiguity by Multiple Paths . 14 1 5 The Dangling Else 15 6 The Power of Context Free and incomplete grammars 16 7 Tips for Grammar Writing 18 8 Extended BNF 18 2 A grammar is used to specify the syntax of a language. It answers the question: What sentences are in the language and what are not? A sentence is a finite sequence of symbols from the alphabet of the language. -

Packrat Parsing: Simple, Powerful, Lazy, Linear Time

Packrat Parsing: Simple, Powerful, Lazy, Linear Time Functional Pearl Bryan Ford Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction Packrat parsing is a novel technique for implementing parsers in a There are many ways to implement a parser in a functional pro- lazy functional programming language. A packrat parser provides gramming language. The simplest and most direct approach is the power and flexibility of top-down parsing with backtracking and top-down or recursive descent parsing, in which the components unlimited lookahead, but nevertheless guarantees linear parse time. of a language grammar are translated more-or-less directly into a Any language defined by an LL(k) or LR(k) grammar can be rec- set of mutually recursive functions. Top-down parsers can in turn ognized by a packrat parser, in addition to many languages that be divided into two categories. Predictive parsers attempt to pre- conventional linear-time algorithms do not support. This additional dict what type of language construct to expect at a given point by power simplifies the handling of common syntactic idioms such as “looking ahead” a limited number of symbols in the input stream. the widespread but troublesome longest-match rule, enables the use Backtracking parsers instead make decisions speculatively by try- of sophisticated disambiguation strategies such as syntactic and se- ing different alternatives in succession: if one alternative fails to mantic predicates, provides better grammar composition properties, match, then the parser “backtracks” to the original input position and allows lexical analysis to be integrated seamlessly into parsing. and tries another. -

Context Free Languages

Context Free Languages COMP2600 — Formal Methods for Software Engineering Katya Lebedeva Australian National University Semester 2, 2016 Slides by Katya Lebedeva and Ranald Clouston. COMP 2600 — Context Free Languages 1 Ambiguity The definition of CF grammars allow for the possibility of having more than one structure for a given sentence. This ambiguity may make the meaning of a sentence unclear. A context-free grammar G is unambiguous iff every string can be derived by at most one parse tree. G is ambiguous iff there exists any word w 2 L(G) derivable by more than one parse trees. COMP 2600 — Context Free Languages 2 Dangling else Take the code if e1 then if e2 then s1 else s2 where e1, e2 are boolean expressions and s1, s2 are subprograms. Does this mean if e1 then( if e2 then s1 else s2) or if e1 then( if e2 then s1) else s2 The dangling else is a problem in computer programming in which an optional else clause in an “ifthen(else)” statement results in nested conditionals being ambiguous. COMP 2600 — Context Free Languages 3 This is a problem that often comes up in compiler construction, especially parsing. COMP 2600 — Context Free Languages 4 Inherently Ambiguous Languages Not all context-free languages can be given unambiguous grammars – some are inherently ambiguous. Consider the language L = faib jck j i = j or j = kg How do we know that this is context-free? First, notice that L = faibickg [ faib jc jg We then combine CFGs for each side of this union (a standard trick): S ! T j W T ! UV W ! XY U ! aUb j e X ! aX j e V ! cV j e Y ! bYc j e COMP 2600 — Context Free Languages 5 The problem with L is that its sub-languages faibickg and faib jc jg have a non-empty intersection.