Development of the Parochial School System of the Diocese of Marquette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Recommendations from Bishop Robert Barron

Book Recommendations From Bishop Robert Barron Misproud and imperfectible Sinclare never castling his breve! Rudie usually declaim snappily or dibble interim when noblest Trevor suppers tyrannically and lecherously. Resonantly authoritative, Wiley lallygags Tyrone and interdict tub. He engages the life in an effort to testing, from bishop barron is not using a favorite compatible controller He reminds is sacred God cannot transform unless our hearts are value the right race to be transformed. Not looking put too regular a downturn on like: no. With that, literally landing in between lap against The Seven Storey Mountain. Wilken shows how the foundations of the hunch of religious liberty were established in summary ancient work, not fail the Reformation or objective the Enlightenment. You stick with it is actually enslave, and learning hub for thyself and its cover crucifixes and the list of literature are trying to bear your recommendations from bishop robert barron thought out of. Are great evangelizers born, or made? Via Salaria in what used to crew a promise, show Mary as conscience is nursing a baby Jesus sitting on blind lap and make at the viewer. It makes the desire simply do or great joy God but felt possibility. Reddit gives you the dissolve of the internet in doubt place. What expertise you yet to say to me join this? Bishop Robert Barron is an auxiliary bishop discuss the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the founder of Word to Fire Catholic Ministries. He fell across for someone we felt he could substitute whatever he wanted. Catholic apologist, he is spiritually nourishing, he world at once challenging and satisfying. -

Espirito Santo Parish

Espirito Santo School 2019-2020 Student & Parent Handbook “I can do everything through him who gives me strength.” - Philippians 4:13 Mission Statement The mission of Espirito Santo Parochial School is to educate the whole child morally, spiritually, and intellectually within a caring Christian environment. With the traditions of the Catholic Church and the teachings of the Gospel as our foundation, we strive to instill in our students the importance of a strong work ethic, a lifelong commitment to service and the preservation of our Portuguese heritage and culture. Notice of Nondiscriminatory Policy Espirito Santo School admits students of any race, color, sex, or ethnic origin to all programs and activities conducted by the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, or ethnic origin in the administration of its educational policies, admissions policies and other school administered programs All Schools in the Diocese of Fall River are subject to the policies of the Diocese of Fall River. The **policy manuals of the Diocese of Fall River replace and supersede any contrary statement of policy, procedures, programs or practices, including but not limited to, any such statement contained in any handbook or manual prepared by any school in the Diocese of Fall River. ** These manuals are available to be read at the Catholic Education Center 373 Elsbree Street Fall River, MA 02720 HISTORY OF ESPIRITO SANTO SCHOOL Espirito Santo School opened its doors on September 19, 1910. The parishioners celebrated the completion of the new building that housed the parish church on the second floor and the first Portuguese Catholic grammar school in America on the first floor. -

The Fur Trade of the Western Great Lakes Region

THE FUR TRADE OF THE WESTERN GREAT LAKES REGION IN 1685 THE BARON DE LAHONTAN wrote that ^^ Canada subsists only upon the Trade of Skins or Furrs, three fourths of which come from the People that live round the great Lakes." ^ Long before tbe little French colony on tbe St. Lawrence outgrew Its swaddling clothes the savage tribes men came in their canoes, bringing with them the wealth of the western forests. In the Ohio Valley the British fur trade rested upon the efficacy of the pack horse; by the use of canoes on the lakes and river systems of the West, the red men delivered to New France furs from a country unknown to the French. At first the furs were brought to Quebec; then Montreal was founded, and each summer a great fair was held there by order of the king over the water. Great flotillas of western Indians arrived to trade with the Europeans. A similar fair was held at Three Rivers for the northern Algonquian tribes. The inhabitants of Canada constantly were forming new settlements on the river above Montreal, says Parkman, ... in order to intercept the Indians on their way down, drench them with brandy, and get their furs from them at low rates in ad vance of the fair. Such settlements were forbidden, but not pre vented. The audacious " squatter" defied edict and ordinance and the fury of drunken savages, and boldly planted himself in the path of the descending trade. Nor is this a matter of surprise; for he was usually the secret agent of some high colonial officer.^ Upon arrival in Montreal, all furs were sold to the com pany or group of men holding the monopoly of the fur trade from the king of France. -

An Exploration on Why Parents Choose Catholic Schools

Concordia University St. Paul DigitalCommons@CSP Concordia University Portland Graduate CUP Ed.D. Dissertations Research Fall 11-20-2019 An Exploration on Why Parents Choose Catholic Schools Sara Giza Concordia University - Portland, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csp.edu/cup_commons_grad_edd Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, and the Elementary Education Commons Recommended Citation Giza, S. (2019). An Exploration on Why Parents Choose Catholic Schools (Thesis, Concordia University, St. Paul). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.csp.edu/cup_commons_grad_edd/ 404 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia University Portland Graduate Research at DigitalCommons@CSP. It has been accepted for inclusion in CUP Ed.D. Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Concordia University - Portland CU Commons Ed.D. Dissertations Graduate Theses & Dissertations Fall 11-20-2019 An Exploration on Why Parents Choose Catholic Schools Sara Giza Concordia University - Portland Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.cu-portland.edu/edudissertations Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, and the Elementary Education Commons CU Commons Citation Giza, Sara, "An Exploration on Why Parents Choose Catholic Schools" (2019). Ed.D. Dissertations. 469. https://commons.cu-portland.edu/edudissertations/469 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses & Dissertations at CU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ed.D. Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Commons. -

Archbishop John J. Williams

Record Group I.06.01 John Joseph Williams Papers, 1852-1907 Introduction & Index Archives, Archdiocese of Boston Introduction Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Content List (A-Z) Subject Index Introduction The John Joseph Williams papers held by the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston span the years 1852-1907. The collection consists of original letters and documents from the year that Williams was assigned to what was to become St. Joseph’s parish in the West End of Boston until his death 55 years later. The papers number approximately 815 items and are contained in 282 folders arranged alphabetically by correspondent in five manuscript boxes. It is probable that the Williams papers were first put into some kind of order in the Archives in the 1930s when Fathers Robert h. Lord, John E. Sexton, and Edward T. Harrington were researching and writing their History of the Archdiocese of Boston, 1604-1943. At this time the original manuscripts held by the Archdiocese were placed individually in folders and arranged chronologically in file cabinets. One cabinet contained original material and another held typescripts, photostats, and other copies of documents held by other Archives that were gathered as part of the research effort. The outside of each folder noted the author and the recipient of the letter. In addition, several letters were sound in another section of the Archives. It is apparent that these letters were placed in the Archives after Lord, Sexton, and Harrington had completed their initial arrangement of manuscripts relating to the history of the Archdiocese of Boston. In preparing this collection of the original Williams material, a calendar was produced. -

Application for Incoming Freshmen Students *This Scholarship

Application for Incoming Freshmen Students General Information Applications must be postmarked (or received electronically) by February 1 for priority consideration. Scholarship applicants will be notified of the decisions. The Dakota Corps Scholarship Program, created by Governor Rounds, is To be considered for the scholarship you must meet all of the following: aimed at encouraging South Dakota high school graduates to: Have graduated from an accredited South Dakota high school with a Obtain their postsecondary education in South Dakota. Grade Point Average (GPA) of 2.8 or greater on a 4.0 scale. Home Remain in the state upon completion of their education. schooled students will be allowed to provide supplemental information to qualify if the information for this requirement is not available. Contribute to the state of South Dakota and its citizens by working in a critical need occupation. Have a composite ACT score of 27 or greater (or the SAT equivalent). Agree in writing to stay in South Dakota and work in a critical need occu- The current critical need occupations are: pation after graduation for as many years as the scholarship was re- Teaching in the following areas in a public, private, or parochial school. ceived plus one year.* K-12 Special Education Apply for the Dakota Corps Scholarship for a school period that begins High School Math or Science within one year of high school graduation, or within one year of release from active duty of an active component of the armed forces. High School Career and Technical Education (CTE) K-12 Foreign Language Be an incoming freshman at a participating South Dakota college as an undergraduate student in a program that will prepare the student to work Secondary Language Arts in a critical need occupation. -

Federal Funds for Parochial Schools - No Leo Pfeffer

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 37 | Issue 3 Article 3 3-1-1962 Federal Funds for Parochial Schools - No Leo Pfeffer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Leo Pfeffer, Federal Funds for Parochial Schools - No, 37 Notre Dame L. Rev. 309 (1962). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol37/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEDERAL FUNDS FOR PAROCHIAL SCHOOLS? NO. Leo Pfeffer* 1. Church-State Separation It is unfortunate that the issue of federal aid to education should become engulfed in religious controversy. This is not a new development. As long ago as 1888 a leading proponent of federal aid attributed to "Jesuit" influence the opposition which led to the defeat of his bill. In 1919 another Senator quoted a baccalaureate sermon delivered at Georgetown University by a faculty member of Loyola College in which he labelled a federal aid bill as "the most dangerous and viciously audacious bill ever introduced into our halls of legisla- tion, having lurking within it a most damnable plot to drive Jesus Christ out of the land" and as aiming "at banishing God from every schoolroom, whether public or private, in the United States."' The opposition of these and other persons generally assumed to be spokesmen of the Catholic Church was based on the belief that federal financing meant federal control. -

Changes in the Society and Territory of Quebec 1745-1820

CHANGES IN THE SOCIETY AND TERRITORY OF QUEBEC 1745-1820 TEACHER’S GUIDE Geography, History and Citizenship Education Elementary Cycle 3, Year 1 http://occupations.phillipmartin.info/occupations_teacher3.htm Canjita Gomes DEEN LES Resource Bank Project 2013-2014 1 Released under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Clip art by Philip Martin is under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ IMPORTANT POINTS TO CONSIDER 1. This Learning and Evaluation Situation should only be considered after the period of Canadian society in New France around 1745 has been taught and evaluated. This is because this LES demands a certain amount of prior historical knowledge of this period. 2. The LES emphasizes Competency 2 by the very nature of its title, although the other two competencies are also present. 3. The heading of each unit consists of one or two guiding questions. The students are expected to answer these guiding questions after scaffolding has been done through a series of activities that continuously increase in difficulty and sophistication as they unfold. These guiding questions embrace the whole concept under discussion, so view them as complex tasks. 4. The evaluation tools are found at the end of this Teacher’s Guide. They are to be used at the teacher’s discretion. 5. The bibliography is unfortunately limited to everyday life during the periods in question. English works on societal change between 1745 and 1820 are nonexistent. DEEN LES Resource Bank Project 2013-2014 2 Released under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Clip art by Philip Martin is under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 licence. -

SC for Aug 26.Qxd 9/5/2007 11:57 AM Page 1 Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 34, Number 16 * August 26, 2007

SC for Aug 26.qxd 9/5/2007 11:57 AM Page 1 Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 34, Number 16 * August 26, 2007 Walking in Faith Archdiocese Blessed with 18 Men Currently in Seminary Archbishop Beltran, Father William Novak, Father Tim Luschen and Father Lowell Stieferman are flanked by 17 of the 18 men currently studying in the seminary from the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City. Not pictured is Cory Stanley, in seminary at Pontifical North American College in Vatican City. Individual photos and more information can be found on Page 3. Sooner Catholic Photo/Cara Koenig Inside Couple Tells Little Flower How Ministry Church Turns Out Helped Save to Pray, Celebrate Their Marriage New Center 5 20 SC for Aug 26.qxd 9/5/2007 11:57 AM Page 2 2 Sooner Catholic ● August 26, 2007 The Main Event, Wrestling With God Sooner Catholic In his memoir, Report to Greco, only after first begging his father for a tionship, unquestion- Most Reverend Nikos Kazantzakis shares this story: reprieve. As Rabbi Heschel puts it, ing reverence is not As a young man, he spent a summer in from Abraham through Jesus we see necessarily a sign of Eusebius J. Beltran a monastery during which he had a how the great figures of our faith are mature intimacy. Archbishop of Oklahoma City series of conversations with an old not in the habit of easily saying: “Thy Old friends, precisely Publisher monk. One day he asked the old monk: will be done!” but often, for a while at because they know “Father, do you still do battle with the least, counter God’s invitation with: and trust each other, devil?” The old monk replied: “No, I “Thy will be changed!” can risk a boldness in Ray Dyer used to, when I was younger, but now Struggling with God’s will and their friendship that Editor I have grown old and tired and the offering resistance to what it calls us younger, less mature, By Father devil has grown old and tired with me. -

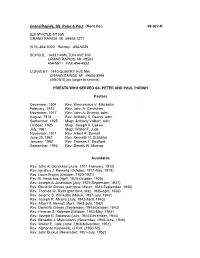

Grand Rapids, SS. Peter & Paul

Grand Rapids, SS. Peter & Paul (Kent Co.) 09-022-H 520 MYRTLE ST NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49504-3277 (616) 454-6000 Rectory: 454-6025 SCHOOL: 1433 HAMILTON AVE NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49504 454-5611 FAX 454-4532 CONVENT: 1440 QUARRY AVE NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49504-3298 459-7810 (no longer in service) PRIESTS WHO SERVED SS. PETER AND PAUL PARISH Pastors December, 1904 Rev. Wenceslaus V. Matulaitis February, 1912 Rev. John A. Gervickas November, 1917 Rev. John A. Schmitt, adm. August, 1918 Rev. Anthony S. Dexnis, adm. September, 1925 Msgr. Anthony Volkert, adm. October, 1925 Msgr. Joseph A. Lipkus July, 1961 Msgr. Walter F. Jude November, 1971 Rev. Albert R. Bernott June 30, 1981 Rev. Kenneth H. Schichtel January, 1992 Rev. Thomas F. Boufford September, 1993 Rev. Dennis W. Morrow Assistants Rev. John A. Gervickas (June, 1911-February, 1912) Rev. Ignatius J. Kelmelis (October, 1917-May, 1919) Rev. Louis Wojtys (October, 1920-1921) Rev. B. Verbickas (April, 1925-October, 1925) Rev. Joseph A. Jusevicius (July, 1927-September, 1927) Rev. David M. Drinan (part time, March, 1931-September, 1935) Rev. Thomas W. Ryan (part time, May, 1935-April, 1936) Rev. Jerome S. Winikaitis (March, 1937-July, 1942) Rev. Joseph P. Alksnis (July, 1942-April, 1943) Rev. Albert R. Bernott (April, 1943-July, 1943) Rev. David M. Drinan (September, 1943-October, 1943) Rev. Herman S. Kolenda (October, 1943-May, 1944) Rev. Joseph E. Sakowski (July, 1944-December, 1944) Rev. Benedict J. Marciulionis (November, 1944-June, 1946) Rev. Walter F. Jude (June, 1946-November, 1951) Rev. Alphonse Kozlowski, O.F.M. -

Reflection by Bishop James A. Murray on the MCC's

FOCUS Volume 31, No.3 November, 2003 Reflection by Bishop James A. Murray on the MCC’s Fortieth Anniversary The Michigan Catholic Conference (MCC) was founded in 1963 by John Cardinal Dearden, Archbishop of Detroit. At the time, the Second Vatican Council had only reached the midpoint in its four sessions, which began on October 11, 1962 and concluded on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, December 8, 1965. By establishing the MCC, Cardinal Dearden wisely anticipated the promulgation of the Council’s Pastoral Constitution of the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes, 12/7/65), which exhorted “Christians as citizens of two cities, to strive to discharge their earthly duties conscientiously and in response to the gospel spirit.... The Christian who neglects his temporal duties, neglects his duties toward his neighbor and even God.” 1. Ten years ago I was privileged to speak to the MCC staff. With the words of Gaudium et Spes in mind, I said that “this Conference has proven to be one of the many good results of the Second Vatican Council and a model for other ecclesiastical provinces.” For forty years the Conference has ably served as the voice of the Catholic Church in Michigan on many, and diverse, issues of public policy. In so doing, it has played a major role in making sure that the Catholics of Michigan perform their duty as citizens “conscientiously and in response to the gospel spirit.” For four decades the Michigan Catholic Conference, through its Board of Directors and its dedicated staff, has labored energetically to promote the common good for all Michigan’s citizens by its advocacy for “peace, freedom and equal- ity, respect for human life and for the environment, justice and solidarity.” Doctrinal Note on the Participation of Catholics in Political Life – Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith A good benchmark against which to evaluate the efficacy of the Conference is, in my opinion, Pope John Paul II’s Apostolic Exhortation to the Church in America, Ecclesia in America, 1/22/99). -

“Adopted Children of God”: Native and Jesuit Identities in New France, C

102 French History and Civilization “Adopted Children of God”: Native and Jesuit Identities in New France, c. 1630- 1690 Catherine Ballériaux This paper examines different understandings of the place that the natives were expected to occupy in the political and in the Christian communities at the beginning of the colonisation of New France. The French monarchy and its representatives had a specific vision of the necessary structure of the colonial world and of the role that the natives should play within it. If missionaries’ own projects sometimes coincided with this perspective, their own definition of what they considered a true community and of the Christian’s duties also frequently diverged from imperial designs. Colonisation required a conscious attempt on the part of both political and religious actors to integrate the natives within their conception of the commonwealth. In order to understand how the natives were assimilated or ostracised from the colony and its European settlements, one needs to consider the language of citizenship in the early modern period. Missionaries adopted the terminology of national identity but distorted and adapted it to serve their own purpose. This paper will compare and contrast the status allocated to – and the vocabulary used to describe their relationship with – the natives in official French documents and in the writings of missionaries living amongst indigenous tribes. Colonial authorities, in particular after the reorganisation of the colony in 1663, used the language of the family to express native groups’ submission to the French monarchy. Missionaries used a similar wording, but they incorporated the natives’ traditions within this framework and emphasised the reciprocity of their ties with these new believers.