Central Asia the Caucasus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investment Projects of the Republic of Dagestan Index

INVESTMENT PROJECTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF DAGESTAN INDEX INNOVATION Construction of a round and shaped steel tubes ............................. 00 producing plant Construction of the “Mountain Resources” .........................................00 Development of in-car electronics manufacturing .........................00 education and display center in Makhachkala (audio sets, starters, alternators) Construction of an IT-park of complete ............................................... 00 Construction of the “Viaduk” customs ..................................................00 “idea-series” cycle type and logistics centre Development of high-effi ciency .............................................................00 Reconstruction of the Makhachkala ..................................................... 00 solar cells and modules production commercial sea port (facilities of the second stage) Construction of the KamAZ vehicles trade ......................................... 00 INDUSTRY AND TRANSPORT and service centers in the districts of the Republic of Dagestan Development of fl oat glass production............................................... 00 Investment sites ...........................................................................................00 Development of nitric and sulfuric acid, .............................................00 and high analysis fertilizer production FUEL AND ENERGY COMPLEX onsite the “Dagfos” OJSC – II stage Construction of an intra-zone .................................................................00 -

Russian Analytical Digest No 72

No. 72 9 February 2010 russian analytical digest www.res.ethz.ch www.laender-analysen.de HISTORY WRITING AND NATIONAL MYTH-MAKING IN RUSSIA ■ The Politics of the Past in Russia 2 By Alexey Miller, Moscow ■■OpiniOn Poll Russian Opinions on History Textbooks 5 ■ The Victory Myth and Russia’s Identity 6 By Ivo Mijnssen, Basel ■■OpiniOn Poll Russian Attitudes towards Stalin 10 Russians on the Disintegration of the USSR 15 ■ Overcoming the Totalitarian Past: Foreign Experience and Russian Problems 16 By Galina Mikhaleva, Moscow German Association for Research Centre for East Center for Security Institute of History DGO East European Studies European Studies, Bremen Studies, ETH Zurich University of Basel russian analytical russian analytical digest 72/10 digest The■politics■of■the■past■in■Russia* By Alexey Miller, Moscow Abstract Active political intervention in the politics of memory and the professional historian’s sphere began no later than in 2006 in Russia. Today all the basic elements of the politics of the past are present: attempts to in- culcate in school a single, centrally-defined, politicized history textbook; the creation of special, politically- committed structures, which combine the tasks of organizing historical research and controlling the activ- ities of archives and publishers; attempts to legislatively regulate historical interpretations; and, as is typical in such cases, efforts to legitimize and ideologically justify all of these practices. The■Origin■of■History■politics■in■the■post- In a society claiming to be democratic, all these Communist■Space mechanisms evolve. In contrast to the previous In 2004 a group of Polish historians announced that Communist party-state system, the group or party Poland needed to develop and propagate its own politics which holds power at a given time is no longer the of the past or history politics. -

The North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law

The North Caucasus: The Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law Europe Report N°226 | 6 September 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Russia between Decentralisation and the “Vertical of Power” ....................................... 3 A. Federative Relations Today ....................................................................................... 4 B. Local Government ...................................................................................................... 6 C. Funding and budgets ................................................................................................. 6 III. Elections ........................................................................................................................... 9 A. State Duma Elections 2011 ........................................................................................ 9 B. Presidential Elections 2012 ...................................................................................... -

Russia Intelligence

N°70 - January 31 2008 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS SPOTLIGHT P. 1-3 Politics & Government c Medvedev’s Last Battle Before Kremlin Debut SPOTLIGHT c Medvedev’s Last Battle The arrest of Semyon Mogilevich in Moscow on Jan. 23 is a considerable development on Russia’s cur- Before Kremlin Debut rent political landscape. His profile is altogether singular: linked to a crime gang known as “solntsevo” and PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS sought in the United States for money-laundering and fraud, Mogilevich lived an apparently peaceful exis- c Final Stretch for tence in Moscow in the renowned Rublyovka road residential neighborhood in which government figures « Operation Succession » and businessmen rub shoulders. In truth, however, he was involved in at least two types of business. One c Kirillov, Shestakov, was the sale of perfume and cosmetic goods through the firm Arbat Prestige, whose manager and leading Potekhin: the New St. “official” shareholder is Vladimir Nekrasov who was arrested at the same time as Mogilevich as the two left Petersburg Crew in Moscow a restaurant at which they had lunched. The charge that led to their incarceration was evading taxes worth DIPLOMACY around 1.5 million euros and involving companies linked to Arbat Prestige. c Balkans : Putin’s Gets His Revenge The other business to which Mogilevich’s name has been linked since at least 2003 concerns trading in P. 4-7 Business & Networks gas. As Russia Intelligence regularly reported in previous issues, Mogilevich was reportedly the driving force behind the creation of two commercial entities that played a leading role in gas relations between Russia, BEHIND THE SCENE Turkmenistan and Ukraine: EuralTransGaz first and then RosUkrEnergo later. -

The Politics of Memory in Russia

Thomas Sherlock Confronting the Stalinist Past: The Politics of Memory in Russia Attempting to reverse the decline of the Russian state, economy, and society, President Dmitry Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin have paid increasing attention over the past two years to the modernization of Russia’s socioeconomic system. Aware of the importance of cultural and ideological supports for reform, both leaders are developing a ‘‘useable’’ past that promotes anti-Stalinism, challenging the anti-liberal historical narratives of Putin’s presidency from 2000—2008. This important political development was abrupt and unexpected in Russia and the West. In mid—2009, a respected journal noted in its introduction to a special issue on Russian history and politics: ‘‘turning a blind eye to the crimes of the communist regime, Russia’s political leadership is restoring, if only in part, the legacy of Soviet totalitarianism....’’1 In December 2009, Time magazine ran a story entitled ‘‘Rehabilitating Joseph Stalin.’’2 Although the conflicting interests of the regime and the opposition of conservatives are powerful obstacles to a sustained examination of Russia’s controversial Soviet past, the Kremlin has now reined in its recent efforts to burnish the historical image of Josef Stalin, one of the most brutal dictators in history. For now, Medvedev and Putin are bringing the Kremlin more in line with dominant Western assessments of Stalinism. If this initiative continues, it could help liberalize Russia’s official political culture and perhaps its political system. Yet Thomas Sherlock is Professor of Political Science at the United States Military Academy at West Point and the author of Historical Narratives in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Russia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). -

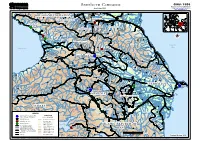

Southern Caucasus Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of June 2003 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS Southern Caucasus Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of June 2003 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected] Znamenskoye)) )) Naurskaya Aki-Yurt ))) Nadterechnaya Dokshukino Malgobek Babayurt RUSSIANRUSSIAN FEDERATIONFEDERATION Chervlennaya ))Nalchik INGUSHETIAINGUSHETIAINGUSHETIA Gudermes KABARDINO-BALKARIAKABARDINO-BALKARIA Sleptsovskaya Grozny Khazavyurt )) Argun )) )) NazranNazran )) ))) NazranNazran )) Kizilyurt Ardon Achkhay-Martan ABKHAZIAABKHAZIA Urus-Martan Shali Alagir )) VladikavkazVladikavkaz CHECHNYACHECHNYA VladikavkazVladikavkaz CHECHNYACHECHNYA SOUTHERNCAUCASUS_A3LC.WOR SukhumiSukhumi )) SukhumiSukhumi )) )) NORTHNORTH OSSETIAOSSETIA )))Vedeno Kaspiysk Nizhniy Unal )) Buynaksk )) Itum-Kali)) Botlikh Shatili)) GaliGali Izberbash !!! ZugdidiZugdidi ZugdidiZugdidi Sergokala SOUTHSOUTH OSSETIAOSSETIA Levashi Tskhinvali Caspian Dagestanskiye Ogni Kareli Sea Black Sea )) Derbent Lanchkhuti )) AkhmetaAkhmeta Khashuri Gori AkhmetaAkhmeta Kvareli Telavi Lagodekhi Gurdzhaani TBILISITBILISI Belakan GEORGIAGEORGIA Kasumkent Batumi)) ADJARIAADJARIA Akhaltsikhe Tsnori Zaqatala Khudat Tsalka Tetri-Tskaro Rustavi Khryuk Khachmas Bolnisi Marneuli Tsiteli-Tskaro Akhalkalaki QAKH Kusary Hopa Shulaveri Kuba Dmanisi Bagdanovka Sheki Divichi Pazar Artvin Alaverdi Akstafa Cayeli Ardahan Oghus Siazan Rize Tauz Mingechaur Lake Tumanyan Gabala Idzhevan Dallyar Dzheir Lagich Kirovakan Shamkhor Gyumri Mingechaur Ismailly Dilizhan Dilmamedli Agdash Geokchay Artik Shamakha Nasosnyy Kars Goranboy Yevlakh Kedabek -

Report on the Mission to Golden Mountains of Altai (Russian

REPORT ON THE MISSION TO GOLDEN MOUNTAINS OF ALTAI WORLD HERITAGE SITE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Kishore Rao, UNESCO/WHC Jens Brüggemann, IUCN 3 TO 8 SEPTEMBER 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..3 Executive Summary and List of Recommendations…………………………….……..4 1. Background to the Mission……………………………………………………….……5 2. National Policy for the World Heritage property……………………………………..6 3. Identification and Assessment of Issues……………………………………………..6 Achievements………………………………….………………………………………6 Plans for the construction of the gas pipeline………………………………………7 Management issues….…………………………………………………………….…9 Dialogue with NGOs………………………………………………………………….12 4. Assessment of the State of Conservation of the property………………...……….12 5. Conclusions and Recommendations…………………………………………….…..13 6. List of Annexes…………………………………………………………………………15 Annex A – Decision of the World Heritage Committee………….………………..16 Annex B – Itinerary and programme………………………………………………..17 Annex C – Description of the Altai project………………………………………….19 Annex D – Maps………………………………………………………………………23 Annex E – Statement of NGOs……………………………………………………...26 Annex F – List of participants of round-table meeting….…………….…………...27 Annex G – Photographs……………………………………………………………...28 2/29 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The mission team would like to thank the Governments of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Altai for their kind invitation, hospitality and assistance throughout the duration of the mission. The UNESCO-IUCN team was accompanied on the mission from Moscow by Gregory Ordjonikidze, Secretary General of the Russian National Commission for UNESCO and his staff Aysur Belekova, as well as by Alexey Troetsky of the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Yuri Badenkov of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Two representatives of Green Peace Russia – Andrey Petrov and Mikhail Kreyndlin also travelled from Moscow to Altai Republic and met the mission team on several occasions. The mission team is extremely grateful to each one of them for their kindness and support. -

Dismemberment of Azerbaijani Lands: Emergence of Southern Dagestan on Russian Empire’S Map

History Sevinj ALIYEVA, Doctor of History Dismemberment of Azerbaijani lands: emergence of Southern Dagestan on Russian Empire’s map Map of the Transcaucasia in 1809-1817 (By N. S. Anosov, 1902) 24 www.irs-az.com 2(25), SUMMER 2016 Derbent. Modern reproduction of a picture by G. Sergeyev (1796) The geopolitical situation in the Caucasus in the and Dagestani rulers to the spread of Russian power first third of the 19th century was due to the desire of in the South Caucasus, territories occupied by Russian the Russian Empire for complete domination in the troops were incorporated into Georgia step by step. In region. The global competition of the Russian Empire 1804, Russian troops occupied more Azerbaijani lands: with the Ottoman Empire and Iran ended with the the Ganja khanate in 1805, the Karabakh, Sheki and Shir- conquest and incorporation of the Caucasus into Rus- van khanates in 1806, and the Baku, Guba and Derbent sia and the spread of the administrative-legal and so- khanates in 1806. In Derbent Province (Ulus, Karakaytag cioeconomic order of the Russian Empire to the region and Tabasaran mahals) most of the state-owned villag- in the 1830-1840s. ers were ruled by bays. The Ulus mahal, which consisted Russian Emperor Alexander I, like Paul I, hoped to of nine villages (389 yards), was the property of Sheykhali limit himself to the formation of “a union under the su- Khan of Guba until 1806. The Russian government first preme patronage” of the Russian Empire from the lands recognized Sheykhali Khan as Khan of Derbent (he was of Northern Azerbaijan and Dagestan (Georgiyevsk, 26 Khan of Guba, and after the death of his brother Hassan December 1802). -

Democracy and Minority Rights in Azerbaijan in Light of the 2013 Presidential Elections Report on Fact-Finding Mission to Dagestan and Azerbaijan September 2013

UNPO Democracy and Minority Rights in Azerbaijan in light of the 2013 presidential elections Report on Fact-Finding Mission to Dagestan and Azerbaijan September 2013 1 Summary After the collapse of the Soviet Union, and in the wake of the Chechen war, the border between Azerbaijan and Russia was closed. The Lezghin people, an ethnic group indigenous to the Caucasus, found itself split between two states. The fact-finding mission to Dagestan and Azerbaijan aimed at examining the situation of the Lezghin, and other ethnic and religious groups, in light of the Azeri Presidential elections of 9 October 2013. Political Representation, Socio-Economic Conditions and Culture and Language were the three key thematics on which the mission gathered data and testimonies. Due to the political make-up and geographical location of the Republic of Dagestan, the distribution of wealth and resources doesn’t target the Lezghin as major beneficiaries. Even though 14 nationalities are officially represented and protected, the lack of official quota for public offices, and unwritten rules about ethnic representation, constitute a threat to the political representation of the Lezghin. Protection and support to native languages is provided by local administrations, and attempts are made to reinvigorate the use of local languages. The dominance of Russian in administration does pose a threat to the indigenous languages. 2 Artistic expression typical for ethnic traditions are encouraged and aim at connecting different ethnic and 3 religious groups. The fate of evicted villagers of former Russian exclaves in Azerbaijan, such as the village of Hrah-Uba, remains worrying. Examining the same thematics and the same ethnic group right across the border in Azerbaijan raised major concerns. -

CORRUPTION PIPELINE: the Threat of Nord Stream 2 to EU Security and Democracy

CORRUPTION PIPELINE: the threat of Nord Stream 2 to EU Security and Democracy Ilya Zaslavskiy Ilya Zaslavskiy | Corruption Pipeline: The Threat of Nord Stream 2 to EU Security and Democracy | Free Russia Foundation, 2017 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 NS2 AS A TOOL OF KREMLIN’S POLITICAL INFLUENCE AGAINST NEIGHBORS AND CORRUPTION 4 ACTUAL RESULTS OF NORD STREAM 1 7 ROOTS OF GAZPROM’S APPEASEMENT IN EUROPE 10 IMPLICATIONS OF NS2 FOR WESTERN POLICY-MAKERS 16 Corruption Pipeline: The Threat of Nord Stream 2 CONTENTS to EU Security and Democracy I. INTRODUCTION his paper is a continuation of publications on security architecture. This Moscow-led pipeline Tthe Kremlin’s subversive activity in Europe seemingly being served as a free and lucrative prepared by Free Russia Foundation. The first gift to European energy corporations in reality paper, The Kremlin’s Gas Games in Europe, comes at the expense of taxpayers and the published jointly with the Atlantic Council, reasonable long-term development of gas looked at Gazprom’s overall current tactics in resources in Russia. Nord Stream 1 and 2 have Europe, including its pipeline plans, energy already started bringing the Kremlin’s business propaganda, and other policies.1 However, after practices and political cooptation to Europe, and our presentations in the US and Europe earlier they will further undermine EU aspirations for this year,2 we realized that a separate paper better governance, democratic institutions and specifically focused on certain aspects of Nord security. Stream 2 was required. To understand why this development is accepted Gazprom and its Western partners that are slated in Germany, and meets with weak and confused to benefit from Nord Stream 2 are aggressively resistance in the EU, it is important to look at advancing the pipeline as a purely commercial the roots of the friendship between big Western project that will only bring benefits to Europe. -

Russia's Dagestan: Conflict Causes

RUSSIA’S DAGESTAN: CONFLICT CAUSES Europe Report N°192 – 3 June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. A FRAGILE INTER-ETHNIC BALANCE.................................................................... 2 A. INTER-ETHNIC COMPETITION OVER LAND AND STATE POSITIONS...............................................2 B. THE 2007 ELECTIONS .................................................................................................................4 1. Removing inter-ethnic competition from electoral politics..................................................4 2. Electoral violence and results ...............................................................................................5 III. ISLAMISM IN DAGESTAN AND CHECHEN CONNECTIONS.............................. 6 A. CHECHEN AND DAGESTANI ISLAMISTS IN THE 1990S .................................................................6 B. THE “HUNT FOR THE WAHHABIS” SINCE 1999 ...........................................................................8 C. SHARIAT JAMAAT’S GROWING INFLUENCE .................................................................................8 D. RENEWED TENSIONS WITH CHECHNYA .....................................................................................10 IV. VIOLENCE AGAINST STATE AUTHORITIES ...................................................... -

Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documenta

ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documenta... Page 1 of 42 Document #2011188 ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation English Version below https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2011188.html 10/22/2019 ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Docume... Page 19 of 42 ecoi.net's featured topics offer an overview on selected issues. The featured topic for the Russian Federation covers the general security situation and a chronology of security-related events in Dagestan since January 2011. The featured topics are presented in the form of excerpts from documents, coming from selected sources. Compiled by ACCORD. https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2011188.html 10/22/2019 ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Docume... Page 20 of 42 Archived version - last update: 21 March 2019. Updated versions of this featured topic are published on the respective country page. 1. Overview (https://ecoi2.ecoi.net/local_link/358745/504747_de.html#Toc489358359) 1.1. Religious conflict 2. Insurgency in Dagestan 2.1. Development of the insurgency 2.2. Attacks and violations of human rights 3. Timeline of attacks in Dagestan 4. Sources 1. Overview “Mit rund drei Millionen Einwohnern ist es die mit Abstand größte kaukasische Teilrepublik, und wegen seiner Lage am Kaspischen Meer bildet es für Russland einen strategisch wichtigen Teil dieser Region. Zugleich leben hier auf einem Territorium von der Größe Bayerns drei Dutzend autochthone Nationalitäten. Damit ist Dagestan das Gebiet mit der größten ethnischen Vielfalt nicht nur im Kaukasus, sondern im gesamten postsowjetischen Raum.“ (SWP, April 2015, p.