Discrimination Against Palestinian Citizens in the Budget of Jerusalem Municipality and Government Planning: Objectives, Forms, Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Next Jerusalem

The Next Introduction1 Jerusalem: Since the beginning of the Israeli-Palestinian Potential Futures conflict, the city of Jerusalem has been the subject of a number of transformations that of the Urban Fabric have radically changed its urban structure. Francesco Chiodelli Both the Israelis and the Palestinians have implemented different spatial measures in pursuit of their disparate political aims. However, it is the Israeli authorities who have played the key role in the process of the “political transformation” of the Holy City’s urban fabric, with the occupied territories of East Jerusalem, in particular, being the object of Israeli spatial action. Their aim has been the prevention of any possible attempt to re-divide the city.2 In fact, the military conquest in 1967 was not by itself sufficient to assure Israel that it had full and permanent The wall at Abu Dis. Source: Photo by Federica control of the “unified” city – actually, the Cozzio (2012) international community never recognized [ 50 ] The Next Jerusalem: Potential Futures of the Urban Fabric the 1967 Israeli annexation of the Palestinian territories, and the Palestinians never ceased claiming East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state. So, since June 1967, after the overtly military phase of the conflict, Israeli authorities have implemented an “urban consolidation phase,” with the aim of making the military conquests irreversible precisely by modifying the urban space. Over the years, while there have been no substantial advances in terms of diplomatic agreements between the Israelis and the Palestinians about the status of Jerusalem, the spatial configuration of the city has changed constantly and quite unilaterally. -

Marah Al-Bakri (Website of 48Arab)

November 2, 2015 Initial Findings of the Profile of Palestinian Terrorists Who Carried Out Attacks in Israel in the Current Wave of Terrorism (Updated to October 25, 2015) The contagious effect of stabbing attacks: a notice posted to the Palestinian social networks, some of them affiliated with Hamas, reading "If you don't stand up for Jerusalem, who will?" It features recent postings written by terrorist operatives Muhannad Shafiq and Fadi Aloun, who were killed carrying out stabbing attacks in Jerusalem and became role models for terrorists who followed in their footsteps. Overview 1. The wave of Palestinian violence and terrorism currently plaguing Israel began during the most recent Jewish High Holidays. In retrospect, the ITIC has concluded it began with the stones thrown at the vehicle of Alexander Levlowitz near the Armon Hanatziv neighborhood of Jerusalem on September 14, 2015. Initially the wave of violence and terrorism focused on the Temple Mount and east Jerusalem and later spread throughout Jerusalem and to other sites inside Israel and various hotspots in Judea and Samaria (especially the region around Hebron). So far 12 1 Israelis and more than 70 Palestinians have been killed. 1 According to a spokesman of the Palestinian ministry of health so far 61 Palestinians have been killed (Voice of Palestine Radio, October 26, 2015). According to the written Palestinian media 71 Palestinians 179-15 2 2. The current wave of violence and terrorism is part of the overall "popular resistance" strategy adopted by the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Fatah at the Sixth Fatah Conference in August 2009.2 It is manifested by rising and falling levels of popular terrorism. -

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, village, and town in the Jerusalem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all villages in Jerusalem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in the Jerusalem Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Jerusalem Governorate. -

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS"..... -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

P3 2.E$S Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2015 LOCAL Fugitives, one sentenced to life, arrested in Jahra KUWAIT: Jahra detectives arrested three persons wanted on multiple charges. They include Bader K, Syrian and sen- tenced to five years in jail, Mutlaq A, Kuwaiti and sentenced to five years, and Hussein K, Bedoon (stateless) and sen- tenced to 90 years in jail, or life in prison. The third suspect was arrested inside his house during a police raid. The three were sent to concerned authorities. Gas station burglar caught Meanwhile, Mubarak Al-Kabeer detectives arrested a Kuwaiti man accused of committing a robbery at a gas sta- tion in Adan earlier. The suspect reportedly drove a car that did not carry any license plates. The suspect works for the same company that owns the station he robbed, the Interior Ministry said in a statement. He was sent to con- cerned authorities. Traffic campaign Separately, Hawally police carried out a traffic campaign that resulted in issuing 580 tickets, impounding 55 cars and arresting three persons on different charges. The Adan gas station robbery suspect. The suspects Bader K, Mutlaq A and Hussein K pictured in these handout photos. Crime Report KDF demands releasing detained activists By A Saleh being investigated by the interior ministry. In a statement KMA issued after a doctor KUWAIT: Kuwait Democratic Forum’s (KDF) was accused of causing the death of a Secretary General Bandar Al-Khairan called female citizen he operated on, KMA for issuing a pardon to all those who had Secretary General Dr Mohammed Al-Qenae been prosecuted during a period when stressed that reports about the woman’s “political situations were not favorable”. -

Gulf Affairs

Autumn 2016 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Identity & Culture in the 21st Century Gulf Featuring H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali Minister of Culture and Sports State of Qatar H.E. Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa President Bahrain Authority for Culture & Antiquities Ali Al-Youha Secretary General Kuwait National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters Nada Al Hassan Chief of Arab States Unit UNESCO Foreword by Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Partnerships: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Jamie Etheridge Chief Copy Editor: Jack Hoover Arabic Content Lead: Lolwah Al-Khater Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Communications Manager: Aisha Fakhroo Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Research Assistant: Matthew Greene Copyright © 2016 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2016 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College, or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication. -

To View Online Click Here

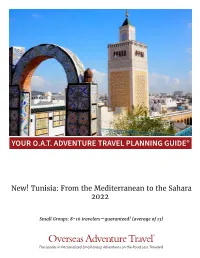

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Venture out to the Tataouine villages of Chenini and Ksar Hedada. In Chenini, your small group will interact with locals and explore the series of rock and mud-brick houses that are seemingly etched into the honey-hued hills. After sitting down for lunch in a local restaurant, you’ll experience Ksar Hedada, where you’ll continue your people-to-people discoveries as you visit a local market and meet local residents. You’ll also meet with a local activist at a coffee shop in Tunis’ main medina to discuss social issues facing their community. You’ll get a personal perspective on these issues that only a local can offer. The way we see it, you’ve come a long way to experience the true culture—not some fairytale version of it. So we keep our groups small, with only 8-16 travelers (average 13) to ensure that your encounters with local people are as intimate and authentic as possible. -

The Upper Kidron Valley

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi Jerusalem 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study No. 398 The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi This publication was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, San Francisco. 7KHFRQWHQWRIWKLVGRFXPHQWUHÀHFWVWKHDXWKRUV¶RSLQLRQRQO\ Photographs: Maya Choshen, Israel Kimhi, and Flash 90 Linguistic editing (Hebrew): Shlomo Arad Production and printing: Hamutal Appel Pagination and design: Esti Boehm Translation: Sagir International Translations Ltd. © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 92186 http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Israel Kimhi – head of the team and editor of the report Eran Avni – infrastructures, public participation, tourism sites Amir Eidelman – geology Yair Assaf-Shapira – research, mapping, and geographical information systems Malka Greenberg-Raanan – physical planning, development of construction Maya Choshen – population and society Mike Turner – physical planning, development of construction, visual analysis, future development trends Muhamad Nakhal ±UHVLGHQWSDUWLFLSDWLRQKLVWRU\SUR¿OHRIWKH$UDEQHLJKERU- hoods Michal Korach – population and society Israel Kimhi – recommendations for future development, land uses, transport, planning Amnon Ramon – history, religions, sites for conservation Acknowledgments The research team thanks the residents of the Upper Kidron Valley and the Visual Basin of the Old City, and their representatives, for cooperating with the researchers during the course of the study and for their willingness to meet frequently with the team. -

![Jerusalem Municipality Approved [For Deposit] New Jewish Settlement In](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9788/jerusalem-municipality-approved-for-deposit-new-jewish-settlement-in-1079788.webp)

Jerusalem Municipality Approved [For Deposit] New Jewish Settlement In

Jerusalem Municipality Approved [for Deposit] New Jewish Settlement in the Heart of East Jerusalem Neighborhood The Local Planning and Building Committee approved unanimously [for deposit] a plan for construction of 18 housing units for Jewish families in Jabel Mukaber. The Elad NGO, which works to increase the Jewish presence in East Jerusalem, is behind the plan. “We hope that Arabs and Jews will live there in peace,” a city council member said By Moshe Steinmetz [Published March 30, 2016 in Walla! News] The Jerusalem Municipality’s Local Planning and Building Committee approved unanimously [for deposit] today [the Local Committee only issues recommendations on construction plans; final approval is given by the District Committee – IR AMIM] a plan for construction of 18 housing units for Jewish families in the heart of the Jabel Mukaber neighborhood in East Jerusalem. The plan was approved [for deposit] with slight reservations regarding the construction of a synagogue at the spot. It was decided that the synagogue, which is intended to serve the tenants of the compound exclusively, will be built inside the compound without the Municipality’s intervention. This is a plan initiated by Lowell Investments, a company associated with the Elad NGO, which works to increase the Jewish presence in East Jerusalem. A building stands at the site that was built a few years ago and has been occupied since 2012 by security guards hired by Elad. The plan seeks to legalize unlicensed construction done in the building and to approve additional construction. “The Jerusalem Municipality is embracing the Elad NGO and together they are harming all of us,” said Aviv Tatarsky, a researcher for the Ir Amim NGO.