Senator Outerbridge Horsey and Manumission in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Deprived of Their Liberty'

'DEPRIVED OF THEIR LIBERTY': ENEMY PRISONERS AND THE CULTURE OF WAR IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1775-1783 by Trenton Cole Jones A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Trenton Cole Jones All Rights Reserved Abstract Deprived of Their Liberty explores Americans' changing conceptions of legitimate wartime violence by analyzing how the revolutionaries treated their captured enemies, and by asking what their treatment can tell us about the American Revolution more broadly. I suggest that at the commencement of conflict, the revolutionary leadership sought to contain the violence of war according to the prevailing customs of warfare in Europe. These rules of war—or to phrase it differently, the cultural norms of war— emphasized restricting the violence of war to the battlefield and treating enemy prisoners humanely. Only six years later, however, captured British soldiers and seamen, as well as civilian loyalists, languished on board noisome prison ships in Massachusetts and New York, in the lead mines of Connecticut, the jails of Pennsylvania, and the camps of Virginia and Maryland, where they were deprived of their liberty and often their lives by the very government purporting to defend those inalienable rights. My dissertation explores this curious, and heretofore largely unrecognized, transformation in the revolutionaries' conduct of war by looking at the experience of captivity in American hands. Throughout the dissertation, I suggest three principal factors to account for the escalation of violence during the war. From the onset of hostilities, the revolutionaries encountered an obstinate enemy that denied them the status of legitimate combatants, labeling them as rebels and traitors. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Revolutionary Mail Bag Governor Thomas Sim Lee's Correspondence 1779 -1782 from Original Pencil Drawing Hy Robert S

REVOLUTIONARY MAIL BAG GOVERNOR THOMAS SIM LEE'S CORRESPONDENCE 1779 -1782 FROM ORIGINAL PENCIL DRAWING HY ROBERT S. PEABODY, IN POSSESSION OE AUTHOR. REVOLUTIONARY MAIL BAG: GOVERNOR THOMAS SIM LEE'S CORRESPONDENCE, 1779-1782 Edited by HELEN LEE PEABODY HE contents of a chest of several hundred unpublished letters T and papers, belonging to Thomas Sim Lee, Governor of Maryland during the American Revolution, form the basis of the following pages.1 The chest, containing these letters and private papers, together with the rest of his personal possessions, was inherited by his youngest son, John Lee, the only unmarried child still living with his father at the time of his death. John Lee, my grandfather, left his inheritance, the old family mansion, " Needwood," in Frederick County, and all it contained, to my father, Charles Carroll Lee. In this manner the chest of letters descended to the present generation. 1 There is no life of Lee. Standard accounts are to be found in the Dictionary of American Biography, XI, 132, and H.E. Buchholz, Governors of Maryland (Baltimore, 1908), pp. 9-13. 1 2 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE The papers—designated hereafter as the T. S. Lee Collection— when found, comprised over a thousand items. The papers were arranged in packages, tied with tape, and tabulated, which facili tated the onerous task of sorting and reading. Many had to be laid aside, as totally unsuited to a compilation of this kind. These comprised invoices, bills of lading, acknowledgements by London firms of hogsheads of tobacco received, orders for furniture, clothing, household utensils—all, in short, that made up the inter change of life between our Colonial ancestors and British mer chants. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

H. Doc. 108-222

34 Biographical Directory DELEGATES IN THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS CONNECTICUT Dates of Attendance Andrew Adams............................ 1778 Benjamin Huntington................ 1780, Joseph Spencer ........................... 1779 Joseph P. Cooke ............... 1784–1785, 1782–1783, 1788 Jonathan Sturges........................ 1786 1787–1788 Samuel Huntington ................... 1776, James Wadsworth....................... 1784 Silas Deane ....................... 1774–1776 1778–1781, 1783 Jeremiah Wadsworth.................. 1788 Eliphalet Dyer.................. 1774–1779, William S. Johnson........... 1785–1787 William Williams .............. 1776–1777 1782–1783 Richard Law............ 1777, 1781–1782 Oliver Wolcott .................. 1776–1778, Pierpont Edwards ....................... 1788 Stephen M. Mitchell ......... 1785–1788 1780–1783 Oliver Ellsworth................ 1778–1783 Jesse Root.......................... 1778–1782 Titus Hosmer .............................. 1778 Roger Sherman ....... 1774–1781, 1784 Delegates Who Did Not Attend and Dates of Election John Canfield .............................. 1786 William Hillhouse............. 1783, 1785 Joseph Trumbull......................... 1774 Charles C. Chandler................... 1784 William Pitkin............................. 1784 Erastus Wolcott ...... 1774, 1787, 1788 John Chester..................... 1787, 1788 Jedediah Strong...... 1782, 1783, 1784 James Hillhouse ............... 1786, 1788 John Treadwell ....... 1784, 1785, 1787 DELAWARE Dates of Attendance Gunning Bedford, -

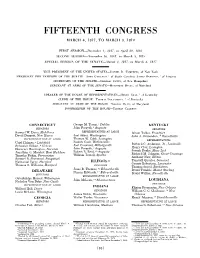

K:\Fm Andrew\11 to 20\15.Xml

FIFTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1817, TO MARCH 3, 1819 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1817, to April 20, 1818 SECOND SESSION—November 16, 1818, to March 3, 1819 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1817, to March 6, 1817 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina; JAMES BARBOUR, 2 of Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 3 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DOUGHERTY, 4 of Kentucky SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT George M. Troup, 7 Dublin KENTUCKY 8 SENATORS John Forsyth, Augusta SENATORS Samuel W. Dana, Middlesex REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Isham Talbot, Frankfort David Daggett, New Haven Joel Abbot, Washington John J. Crittenden, 15 Russellville REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas W. Cobb, Lexington REPRESENTATIVES 5 Zadock Cook, Watkinsville Uriel Holmes, Litchfield Richard C. Anderson, Jr., Louisville 6 Joel Crawford, Milledgeville Sylvester Gilbert, Hebron Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Huntington, Norwich John Forsyth, 9 Augusta Robert R. Reid, 10 Augusta Joseph Desha, Mays Lick Jonathan O. Moseley, East Haddam Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Timothy Pitkin, Farmington William Terrell, Sparta Anthony New, Elkton Samuel B. Sherwood, Saugatuck Tunstall Quarles, Somerset Nathaniel Terry, Hartford ILLINOIS 11 George Robertson, Lancaster Thomas S. Williams, Hartford SENATORS Thomas Speed, Bardstown Jesse B. Thomas, 12 Edwardsville David Trimble, Mount Sterling DELAWARE Ninian Edwards, 13 Edwardsville SENATORS David Walker, Russellville REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE Outerbridge Horsey, Wilmington John McLean, 14 Shawneetown LOUISIANA Nicholas Van Dyke, New Castle SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE INDIANA Willard Hall, Dover Eligius Fromentin, New Orleans SENATORS 16 Louis McLane, Wilmington William C. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1911, Volume 6, Issue No. 2

/V\5A.SC 5^1- i^^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Voi,. VI. JUNE, 1911. No. 2. THE MARYLAND GUARD BATTALION, 1860-61.1 ISAAC F. NICHOLSON. (Bead before the Society April 10, 1911.) After an interval of fifty years, it is permitted the writer to avail of the pen to present to a new generation a modest record of a military organization of most brilliant promise— but whose career was brought to a sudden close after a life of but fifteen months. The years 1858 and 1859 were years of very grave import in the history of our city. Local political conditions had become almost unendurable, the oitizens were intensely incensed and outraged, and were one to ask for a reason for the formation of an additional military organization in those days, a simple reference to the prevailing conditions would be ample reply. For several years previous the City had been ruled by the American or Know Nothing Party who dominated it by violence through the medium of a partisan police and disorderly political clubs. No man of opposing politics, however respectable, ever undertook to cast his vote without danger to his life. 'The corporate name of this organization was "The Maryland Guard" of Baltimore City. Its motto, " Decus et Prsesidium." 117 118 MAEYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZIlfE. The situation was intolerable, and the State at large having gone Democratic, some of our best citizens turned to the Legis- lature for relief and drafted and had passed an Election Law which provided for fair elections, and a Police Law, which took the control of that department from the City and placed it in the hands of the State. -

The Letters of George Plater

(front cover) The Letters of George Plater David G. Brown The Letters of George Plater Compiled and Annotated by David G. Brown Copyright: Historic Sotterley, 2013 This book may not be reproduced or copied, in whole or in part, without prior written permission. Preface This collection of George Plater’s letters is a companion publication to the book, George Plater of Sotterley, published in 2014 by the Chesapeake Book Company. Like all gentlemen of his age, Plater relied on letters as his primary connection with distant family, friends and acquaintances. As strange as it may seem in the interconnected twenty-first century, letters were the only way to stay connected other than word-of-mouth news conveyed by traveling friends. Letters are also a primary source for historians trying to understand an individual’s character and thinking. Fortunately, some of George Plater’s letters have survived the two centuries since his death. These fall into two categories: letters he wrote in various official capacities, for example, as Continental Congress delegate, senate president or governor, and his personal letters. Many of his official letters are available in original records and collections of documents. But even in this group many no longer exist. Some of those missing are historically significant. An example would be the report he sent to the governor and Assembly in his capacity as president of the Maryland Convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution. When this report was received, the Maryland Senate instructed the governor and council to preserve it. Nevertheless, it has been lost. Other lost official letters reported on important developments with which Plater was involved at the Continental Congress. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1937, Volume 32, Issue No. 1

MSA SC 5&81 -1 - U5 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED UNDEK THE AUTHORITY OP THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXXII BALTIMORE 1937 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXII. PAGE JOHN W. M. LEE, 1848-1896. By Ruth Lee Briscoe, 1 LETTEES OF JAMES RUMSET. Edited iy James A. Padgett, Ph.D., 10, 136, 271 A NEW MAP OP THE PEOVIKCB OF MARYLAND IN NORTH AMERICA. By J. Louis Kuethe, 28 BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1633. Contributed by Louis Dow Scisco, 30 LETTERS OF CHARLES CARROLL, BARRISTER. Continued from Vol. XXXI, 4, 35, 174, 348 NOTES, QUERIES, REVIEWS, .... 47, 192, 291, 292, 376, 385 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 53, 190, 381 LIST OP MEMBERS, 73 POE'S LITERARY BALTIMORE. By John C. French, 101 SOME RECENTLY-FOUND POEMS ON THE CALVERTS. By Walter B. Norris, 112 GOVERNOR HORATIO SHABPB AND HIS MARYLAND GOVERNMENT. By Paul H. Giddens, 156 A LOST COPY-BOOK OP CHARLES CARROLL OF CARROLLTON. By J. G. D. Paul, 193 AN UNPUBLISHED LETTER. By Roger B. Taney, 225 HISTORIC FORT WASHINGTON. By Amy Cheney Clinton, .... 228 THE PAPERS OP THE MARYLAND STATE COLONIZATION SOCIETY. By William D. Eoyt, Jr., 247 * " PATOWMECK ABOVE YE INHABITANTS." By William B. Marye, . 293 JOHN NELSON MCJILTON. By W. Bird Terwilliger, 301 THE SIZES OF PLANTATIONS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MARYLAND. By T. J. Wyckoff, 331 INCIDENTS OP THE WAR OP 1812 . From the " Baltimore Patriot," . 340 THE SOCIETY OP THE CINCINNATI, 369 THE ROCKHOLDS OP EARLY MARYLAND. By Nannie Ball Nimmo, . 371 'BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1684. By Louis Dow Scisco 286 ARCHIVES OF M^HYLA^ISro Edited by J. -

Unit History of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776–1781): Insights from the Service Record of Capt

Unit History of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776–1781): Insights from the Service Record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill Tucker F. Hentz 2007 Article citation: Hentz, Tucker F. Unit History of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776–1781): Insights from the Service Record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill. 2007. Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, E259 .H52 2007. http://www.vahistorical.org/research/tann.pdf Unit History of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776-1781): Insights from the Service Record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill Tucker F. Hentz (2007) Details of the origins, formal organization, and service record of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment have defied easy synthesis. Primarily because most of the unit was captured or killed at the battle of Fort Washington on 16 November 1776, the historical trail of the regiment’s “surviving” element has become complex. Modern and contemporaneous accounts of the 1776 New York City Campaign of the War of American Independence convey the impression that the battle marked the end of the regiment as a combat entity. In truth, however, a significant portion of it continued to serve actively in the Continental Army throughout most of the remainder of the war. Adamson Tannehill, a Marylander, was the regiment’s only officer with an uninterrupted service history that extended from the unit’s military roots in mid-1775 until its disbanding in early 1781. His service record thus provided a logical focal point for research that has helped resolve a clearer view of this notable regiment’s heretofore untold history. Antecedents On 14 June 1775 the Continental Congress directed the raising of ten independent companies of riflemen in the Middle Colonies1 as part of the creation of the Continental Army as a national force for opposition to the actions of the British government. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1976, Volume 71, Issue No. 2

ARYLAND AZIN N Published Quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society SUMMER 1976 Vol. 71, No. 2 BOARD OF EDITORS JOSEPH L. ARNOLD, University of Maryland, Baltimore County JEAN BAKER, Goucher College GARY BROWNE, Wayne State University JOSEPH W. COX, Towson State College CURTIS CARROLL DAVIS, Baltimore RICHARD R. DUNCAN. Georgetown University RONALD HOFFMAN, University of Maryland, College Park H. H. WALKER LEWIS, Baltimore EDWARD C. PAPENFUSE, Hall of Records BENJAMIN QUARLES, Morgan State College JOHN B. BOLES. Editor, Towson State College NANCY G. BOLES, Assistant Editor RICHARD J. COX, Manuscripts MARY K. MEYER, Genealogy MARY KATHLEEN THOMSEN, Graphics FORMER EDITORS WILLIAM HAND BROWNE, 1906-1909 LOUIS H, DIELMAN, 1910-1937 JAMES W. FOSTER, 1938-1949, 1950-1951 HARRY AMMON, 1950 FRED SHELLEY, 1951-1955 FRANCIS C. HABER, 1955-1958 RICHARD WALSH, 1958-1967 RICHARD R. DUNCAN, 1967-1974 P. WILLIAM FILBY, Director ROMAINE S. SOMERVILLE, Assistant Director The Maryland Historical Magazine is published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201. Contributions and correspondence relating to articles, book reviews, and any other editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor in care of the Society. All contributions should be submitted in duplicate, double-spaced, and consistent with the form out- lined in A Manual of Style (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969). The Maryland Historical Society disclaims responsibility for statements made by contributors. Composed and printed at Waverly Press. Inc., Baltimore, Maryland 21202. Second-class postage paid at Baltimore, Maryland. © 1976, Maryland Historical Society. K^A ^ 5^'l-2tSZ. I HALL OF RECORDS LIBRARY MARYLAND "^ TSTOBTr/^frQUS, MARYLAND No.