The Formation of Financial Centers: a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20Annual Report 2020 Equiniti Group

EQUINITI GROUP PLC 20ANNUAL REPORT 2020 PURPOSEFULLY DRIVEN | DIGITALLY FOCUSED | FINANCIAL FUTURES FOR ALL Equiniti (EQ) is an international provider of technology and solutions for complex and regulated data and payments, serving blue-chip enterprises and public sector organisations. Our purpose is to care for every customer and simplify each and every transaction. Skilled people and technology-enabled services provide continuity, growth and connectivity for businesses across the world. Designed for those who need them the most, our accessible services are for everyone. Our vision is to help businesses and individuals succeed, creating positive experiences for the millions of people who rely on us for a sustainable future. Our mission is for our people and platforms to connect businesses with markets, engage customers with their investments and allow organisations to grow and transform. 2 Contents Section 01 Strategic Report Headlines 6 COVID-19: Impact And Response 8 About Us 10 Our Business Model 12 Our Technology Platforms 14 Our Markets 16 Our Strategy 18 Our Key Performance Indicators 20 Chairman’s Statement 22 Chief Executive’s Statement 24 Operational Review 26 Financial Review 34 Alternative Performance Measures 40 Environmental, Social and Governance 42 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 51 Viability Statement 56 Section 02 Governance Report Corporate Governance Report 62 Board of Directors 64 Executive Committee 66 Board 68 Audit Committee Report 78 Risk Committee Report 88 Nomination Committee Report 95 Directors' Remuneration -

The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Kenny, Seán; Lennard, Jason; Turner, John D

The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Kenny, Seán; Lennard, Jason; Turner, John D. 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kenny, S., Lennard, J., & Turner, J. D. (2017). The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises: Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938. (Lund Papers in Economic History: General Issues; No. 165). Department of Economic History, Lund University. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Lund Papers in Economic History No. 165, 2017 General Issues The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises: Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Seán Kenny, Jason Lennard & John D. -

Cleveland Naturalists' Field Club and a Valued Contributor, After First Accepting the British

1 CLEVELAND NATURALISTS’ FIELD CLUB RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS 1920 - 1925 VOL.III. Part IV. Edited by Ernest W. Jackson F.I.C., F.G.S. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS (FREE TO MEMBERS) MIDDLESBROUGH; JORDISON AND CO., LTD, PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS 1926 CONTENTS MEMOIR OF W.H. THOMAS - J.W.R. PUNCH 187 ROSEBERRY TOPPING IN FACT AND FICTION - J.J. BURTON, F.G.S. 190 WHITE FLINT NEAR LEALHOLME - EARNEST W. JACKSON, F.I.C. 206 THE MOUND BREAKERS OF CLEVELAND - WILLIAM HORNSBY, B.A 209 PEAT DEPOSITS AT HARTLEPOOL - J INGRAM, B. SC 217 COLEOPTERA OBSERVED IN CLEVELAND - M LAWSON THOMPSON, F.E.S. 222 ORIGIN OF THE FIELD CLUB - THE LATE J.S. CALVERT 226 MEMOIRS OF J.S. CALVERT - J.J. BURTON 229 MEMOIR OF BAKER HUDSON - F ELGEE 233 OFFICERS 1926 President Ernest W Jackson F.I.C., F.G.S Vice-Presidents F Elgee Miss Calvert J J Burton F.G.S. M.L.Thompson F.E.S. J W R Punch T A Lofthouse A.R.I.B.A., F.E.S H Frankland Committee Mrs Hood Miss Cotton C Postgate Miss Vero Dr Robinson P Hood Hon Treasurer H Frankland, Argyle Villa, Whitby Sectional Secretaries Archaeology – P Hood Geology – J J Burton, F.G.S. Botany – Miss Calvert Ornithology ) Conchology ) and ) - T A Lofthouse And )- T A Lofthouse Mammalogy ) F.E.S. Entomology ) F.E.S. Microscopy – Mrs Hood Hon. Secretaries G Knight, 16 Hawthorne Terrace, Eston M Odling, M.A., B.Sc.,”Cherwell,” the Grove, Marton-in-Cleveland Past Presidents 1881 - Dr W Y Veitch M.R.C.S. -

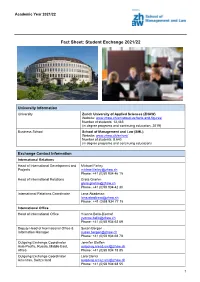

ZHAW SML Fact Sheet 2021-2022.Pdf

Academic Year 2021/22 Fact Sheet: Student Exchange 2021/22 University Information University Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/about-us/facts-and-figures/ Number of students: 13,485 (in degree programs and continuing education, 2019) Business School School of Management and Law (SML) Website: www.zhaw.ch/en/sml/ Number of students: 8,640 (in degree programs and continuing education) Exchange Contact Information International Relations Head of International Development and Michael Farley Projects [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 46 15 Head of International Relations Greta Gnehm [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 42 30 International Relations Coordinator Lena Abadesso [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 77 15 International Office Head of International Office Yvonne Bello-Bischof [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 69 Deputy Head of International Office & Susan Bergen Information Manager [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 78 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Jennifer Steffen Asia-Pacific, Russia, Middle East, [email protected] Africa Phone: +41 (0)58 934 78 85 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Lara Clerici Americas, Switzerland [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 68 55 1 Academic Year 2021/22 Outgoing Exchange Coordinator Miguel Corredera Europe [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 41 02 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Alice Ragueneau Overseas [email protected] Phone: +41 (0)58 934 62 51 Incoming Exchange Coordinator Sandra Aerne Europe -

The Headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England

Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Barnes, V. and Newton, L. (2019) Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England. Management and Organizational History, 14 (3). pp. 213-244. ISSN 1744-9359 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/86938/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 Publisher: Taylor and Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Management & Organizational History ISSN: 1744-9359 (Print) 1744-9367 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rmor20 Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England Victoria Barnes & Lucy Newton To cite this article: Victoria Barnes & Lucy Newton (2019) Symbolism in bank marketing and architecture: the headquarters of National Provincial Bank of England, Management & Organizational History, 14:3, 213-244, DOI: 10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2019.1683038 © 2019 The Author(s). -

John Smart National Archives of Canada

164 ARCHIVARIA 27 Anyone interested in the actions against individuals which are within the capability of the modern democratic state, and in the effect of current legislation on freedom of information and on the privacy of the individual, will find this book useful reading. Mitgang approves highly of freedom-of-information legislation - indeed, he would have had no book without it - but is worried that the Reagan administra- tion has weakened the regulations surrounding these laws, and can give no assur- ance that U.S. agencies are not still compiling files and watching American authors, even though the legislation is now supposed to make that practice illegal. "To this day [authors] can be watched and kept on file through what I consider to be a wide opening in the back door of the guidelines." In fact, the New York Times of 21 August 1988 carried a story entitled "F.B.I. Kept a File on Supreme Court," which outlined how the FBI watched, taped, and wiretapped the judges of the U.S. Supreme Court "from 1932 until at least 1985." As this review is written, a former head of the CIA has become President of the United States. However, neither Canadians in general nor Canadian archivists in particular should permit themselves too many superior glances at the United States when the questions raised by Mitgang's book come up for discussion. In the winter of 1988, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service raided the offices of Radio- Canada in Montreal, and one recalls the RCMP's raid in recent years on the home of Ottawa author John Sawatsky. -

From Next Best to World Class: the People and Events That Have

FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 1 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Other Historical Books by This Author A Thirty Years’ War: The Failed Public Private Partnership that Spurred the Creation of the Toronto Transit Commission, 1891–1921 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2015) Lawyers, Families, and Businesses: A Social History of a Bay Street Law Firm, Faskens 1863–1963 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2013) Damaging Winds: Rumours That Salieri Murdered Mozart Swirl in the Vienna of Beethoven and Schubert (historical novel published as an ebook through the National Arts Centre and the Canadian Opera Company, 2013) The Fiercest Debate: Cecil Wright, the Benchers, and Legal Education in Ontario, 1923–1957 (Osgoode Society and University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1987) with Jerome Bickenbach CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 2 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 3 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Next Best to World Class: The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1967–2017 © Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

2021 Salary Projection Survey Summary

2021 Salary Projection Survey Insights on compensation trends expected in 2021 - Summary report 38th edition | September 2020 Table of contents 1 Introduction 2 Compensation consulting 3 Participant profile 6 Survey highlights 8 Historical base salary increase trend 9 Base salary 11 Salary structure 13 Survey participants 22 Notice 22 For more information Introduction The results presented in this report are an analysis of responses collected between July and August 2020 to the 38th edition of Morneau Shepell’s 2021 Salary Projection Survey. The data represents a broad cross-section of industries representing 889 organizations across Canada and provides data on actual salary budget increase percentages for the past and current years, along with projected increases for next year. • The report contains segmented data and a detailed analysis by Morneau Shepell’s compensation consultants. • Survey participation jumped over 75% on a year over year basis from 506 organizations participating in 2019, to 889 in 2020. Many of these organizations also participated in our 2020 Canadian Salary Surveys. • Survey data includes actual 2020 and projected 2021 base salary increases and salary structure adjustments. • Survey data is reported excluding zeros and including zeros (freezes) but does not include temporary rollbacks due to COVID-19. • Findings are summarized for non-unionized employees. • Statistical requirements applied to the data analysis include a minimum of three organizations for average/mean reported results, and a minimum of five organizations -

BANK MERGERS: IS BIGGER BETTER? Introduction

BANK MERGERS: IS BIGGER BETTER? Introduction In January 1998, the Bank of Montreal and the Royal Bank of Canada announced plans to merge and create one superbank. A few months later, in April, the Toronto Dominion Bank and the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce announced similar plans. The proposed bank mergers caught many people off guard, including Minister of Finance Paul Martin. In a Macleans interview, Martin said, "Just because they decided to get into bed together doesnt mean that I have to bless their union." Martins message seemed to be that Ottawa, not the banks, would decide the future of banking in Canada. "There will be no mergers in the banking sector until we are convinced that [it] is what is best for Canadians, and we will not be stampeded into making that decision." According to the banks, the proposed mergers were a natural response to a changing and highly competitive global marketplace. Mergers, they said, provide a way of maintaining a strong Canadian presence in the banking industry. Certainly, recent technological advances have dramatically changed the manner in which the financial services industry conduct their business, and the above- mentioned banks feel, therefore, that they need to be bigger to compete and to have a substantial presence in the global banking community. Martin himself acknowledged the changed nature of banking when he said, "If you look back at banking five years ago, you might as well look back two centuries." While the proposed bank mergers brought attention to the challenges facing Canadas banks, these challenges are not peculiar to the banks alone. -

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

FSCS Information Sheet

FINANCIAL SERVICES COMPENSATION SCHEME INFORMATION SHEET Basic information about the protection of your eligible deposits Eligible deposits in Bank of Scotland plc are protected by: The Financial Services Compensation Scheme (“FSCS”)1 Limit of protection: £85,000 per depositor per bank2 The following trading names are part of your bank: Halifax, Intelligent Finance (IF), Birmingham Midshires (BM Savings), Bank of Scotland, Bank of Scotland Private Banking, Bank of Wales, and St. James’s Place Bank. Some savings accounts under the AA Savings and Saga brand names are also deposits with Bank of Scotland plc. If you have more eligible deposits at the same bank: All your eligible deposits at the same bank are “aggregated” and the total is subject to the limit of £85,0002 If you have a joint account with other person(s): The limit of £85,000 applies to each depositor separately3 Reimbursement period in case of bank’s failure: 20 working days4 Currency of reimbursement: Pound sterling (GBP, £) To contact Bank of Scotland plc for enquiries relating to You can visit one of our branches, call us, go online or your account: write to us at the address below: The Mound, Edinburgh, EH1 1YZ To contact the FSCS for further information Financial Services Compensation Scheme, on compensation: 10th Floor Beaufort House, 15 St Botolph Street, London, EC3A 7QU Tel: 0800 678 1100 or 020 7741 4100 Email: [email protected] More information: http://www.fscs.org.uk Additional Information 1 Scheme responsible for the protection of your eligible deposit Your eligible deposit is covered by a statutory Deposit Guarantee Scheme. -

France À Fric: the CFA Zone in Africa and Neocolonialism

France à fric: the CFA zone in Africa and neocolonialism Ian Taylor Date of deposit 18 04 2019 Document version Author’s accepted manuscript Access rights Copyright © Global South Ltd. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. This is the author created, accepted version manuscript following peer review and may differ slightly from the final published version. Citation for Taylor, I. C. (2019). France à fric: the CFA Zone in Africa and published version neocolonialism. Third World Quarterly, Latest Articles. Link to published https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1585183 version Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ FRANCE À FRIC: THE CFA ZONE IN AFRICA AND NEOCOLONIALISM Over fifty years after 1960’s “Year of Africa,” most of Francophone Africa continues to be embedded in a set of associations that fit very well with Kwame Nkrumah’s description of neocolonialism, where postcolonial states are de jure independent but in reality constrained through their economic systems so that policy is directed from outside. This article scrutinizes the functioning of the CFA, considering the role the currency has in persistent underdevelopment in most of Francophone Africa. In doing so, the article identifies the CFA as the most blatant example of functioning neocolonialism in Africa today and a critical device that promotes dependency in large parts of the continent. Mainstream analyses of the technical aspects of the CFA have generally focused on the exchange rate and other related matters. However, while important, the real importance of the CFA franc should not be seen as purely economic, but also political.