Humor in Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Shawn Farley at 413-545-4159 Or at [email protected]

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Shawn Farley at 413-545-4159 or at [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: February 13, 2013 WHAT: UPRIGHT CITIZENS BRIGADE TOURING COMPANY RESCHEDULED WHEN: Friday, March 8 at 8 p.m. and 10 p.m. (rescheduled from Friday, February 8 that was postponed due to snow storm) WHERE: Bowker Auditorium University of Massachusetts Amherst TICKETS: General Admission: $20; Five College, GCC, STCC students and youth 17 and under are $10. Call 1-800-999-UMAS or 545-2511 for tickets or go online to http://www.fineartscenter.com/ IMAGES: To download images relating to this press release please go online to IMAGES: To download images relating to this press release please go online to https://fac.umass.edu/Online/PressRoom UPRIGHT CITIZENS BRIGADE BRINGS COMEDY IMPROV TO UMASS “Upright Citizens Brigade -- The CBGB of alternative comedy.” New York Magazine Let’s try this again. The Upright Citizens Brigade Touring Company that was originally scheduled to appear on Friday, February 8 th but had to be postponed due to the snow storm has been rescheduled for Friday March 8th for two shows at 8 p.m. and 10 p.m. Opening the 8 p.m. show will be UMass’ own Vocal Suspects, the premiere co- ed a cappella group. Opening the 10 p.m. show will be UMass’ Mission: Improvable. The Upright Citizens Brigade (UCB) Touring Company cast is hand-picked from the best improv comedians in the country -- a veritable "next wave" of comedy superstars from the theatre that produced Amy Poehler, Horatio Sanz, Ed Helms, UMass alum Rob Corddry, Rob Riggle, Paul Scheer & Rob Huebel and countless others. -

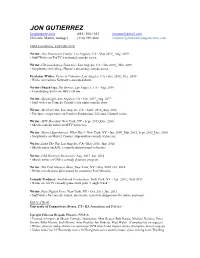

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.Com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, Manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected]

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Writer, This Functional Family, Los Angeles, CA • May 2019_ Aug. 2019 • Staff Writer on TruTV’s animated comedy series. Writer, Ultramechatron Team Go!, Los Angeles, CA • Jan. 2019_ Mar. 2019 • Scriptwriter on College Humor’s streaming comedy series. Freelance Writer, Victor & Valentino, Los Angeles, CA • Oct. 2018_ Dec. 2018 • Writer on Cartoon Network’s animated show. Writer (Punch Up), The Detour, Los Angeles, CA • Aug. 2018 • Contributing writer on TBS’s sitcom. Writer, @midnight, Los Angeles, CA • Feb. 2017_Aug. 2017 • Staff writer on Comedy Central’s late night comedy show. Writer, My Crazy Sex, Los Angeles, CA • April. 2016_Aug. 2016 • Freelance script writer on Painless Productions’ Lifetime Channel series. Writer, MTV Decoded, New York, NY • Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Sketch comedy writer on MTV webseries. Writer, Marvel Superheroes: What The!?, New York, NY • Jan. 2009_May 2012, Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Scriptwriter on Marvel Comics’ stop-motion comedy webseries. Writer, Land The Gig, Los Angeles, CA • May 2016_June 2016 • Sketch writer on AOL’s comedy/instructional webseries. Writer, CBS Diversity Showcase • Aug. 2015_Jan. 2016 • Sketch writer on CBS’s comedy diversity program. Writer, The Paul Mecurio Show, New York, NY • May 2014_Oct. 2014 • Writer on talk show pilot hosted by comedian Paul Mecurio. Comedy Producer, NorthSouth Productions, New York, NY • Apr. 2013_ May 2013 • Writer on TruTV comedy game show pilot “Laugh Truck.” Writer, Fuse Digital News, New York, NY • Oct. 2011_Jan. 2013 • Staff writer for comedy videos, interviews, news hits and promos for online and onair. -

Kathryn Burns Resume

kathryn burns choreographer selected credits contact: (818) 509-0121 FILM Ibiza Dir. Alex Richanbach/ Prod. Will Ferrell, Adam McKay Under the Silver Lake Dir. David Robert Mitchell Other People Chris Kelly, Adam Scott Freak Dance Don’t Think Productions / Dir. Matt Besser The Future Roadside Attractions / Dir. Miranda July Love at The Christmas Table Lifetime TV / Dir. Rachel Goldenberg Escape from Polygamy Lifetime TV / Dir. Rachel Goldenberg High Road Dir. Matt Besser TELEVISION Dispatches From Elsewhere (*to be released) AMC Flirty Dancing (*to be released) FOX Better Things FX Dancing with the Stars (Season 28) ABC Everything’s Gonna Be Okay (*to be released) Freeform Why Women Kill CBS The Morning Show (*to be released) Apple TV+ Esther Povitsky Comedy Special Comedy Central / Dir. Nick Goossen Creative Art’s Emmy’s – Opening Number (2019) FOX Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (Season 1-4) CW Wet Hot American Summer: First Day of Camp Netflix / Dir. David Wain Black Monday Showtime First Wives Club BET+ Adam Ruins Everything Tru TV / Nice Little Day LLC Drunk History Comedy Central Splitting Up Together ABC American Princess Lifetime TV Future Man Hulu Funny Dance Show E! Happy Together - Flash Mob CBS The Other Two Comedy Central After Rap ABC Angie Tribeca TBS Lucifer Netflix/ Fox Let’s Get Physical Pop SMILF Showtime Great News NBC Better Things FX Jimmy Kimmel Live - Logic ABC Walk the Prank Disney XD/Disney Channel Throwing Shade Viacom Bill Nye Saves the World Bunim/Murray Productions The Late Late Show with James Corden CBS Broadcasting, Inc. Michael Bolton’s Big, Sexy Valentine’s Day CBB Productions, INC. -

Long-Form Improv Practices in US Comedy Podcast Culture Smith, AN

Achieving a depth of character : long-form improv practices in US comedy podcast culture Smith, AN http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2040610X.2019.1623500 Title Achieving a depth of character : long-form improv practices in US comedy podcast culture Authors Smith, AN Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/51264/ Published Date 2019 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Achieving a depth of character: Long-form improv practices in US comedy podcast culture Anthony N. Smith Long-form improvised comedy – or long-form improv – has been enduringly significant across media cultures since its development in 20th Century North American theatrical contexts. The comedic mode has been formative to the early development of various successful and influential comedy performers, writers and producers in recent decades, including Mike Myers, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler and Adam McKay (Fotis 2014, 7). It has influenced the scripting and performance processes of many US film comedies, including Anchorman and Knocked Up, and US television sitcoms, such as 30 Rock and Curb Your Enthusiasm.1 It has furthermore recently spread into podcast culture, underpinning various popular podcast series, including Comedy Bang! Bang!, which garners upwards of two million episode downloads per month (Wilstein, 2017). -

Lesley Tsina Web Resume 2012

Lesley Tsina SAG-AFTRA [email protected] Television Funny or Die Presents: Designated Driver Co-Star HBO/Dir. Jason Woliner New Media Asperger’s High Lead Dir. Jason Axinn Scary Girl with Chloe Moretz Supporting Dir. Ryan Perez Prime Suspect: The Hat Lead Dir. Lowell Meyer Murder List Lead Dir. Ryan Perez Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Trailer Supporting Dir. Aaron Greenberg Kate Plus 8 College Years Supporting Dir. Robert Mercado Elevator (webseries) Supporting Dir. Woody Tondorf Election 2008 Ground Zero Supporting Dir. Tom Gianas Craigslist Penis Photographer Featured Dir. Eric Appel Funeral Sex Supporting Dir. Jason Axinn Comedy CBS Diversity Showcase 2012 Sketch Performer CBS/Rick Najera Ask a Hedge Fund Manager (sketch) Sketch Performer NPR - Marketplace Maude Night Sketch Team Member Upright Citizens Brigade Harold Night Improv Team Member Upright Citizens Brigade Lord of the Files Solo Performer Comedy Central Stage Tournament of Nerds Sketch Performer Upright Citizens Brigade Extreme Tambourine Sketch Performer Comedy Central Stage Slave Leia Improv Team Member IO West – Mainstage SF Sketchfest – Extreme Tambourine Sketch Performer Dark Room, SF San Francisco Improv Festival Improv Performer Eureka Theatre, SF Comedy Death-Ray Stand-up Comic Upright Citizens Brigade Hothouse Comedy Show Stand-up Comic RZO/Hothouse Tomorrow Show Stand-up Comic Steve Allen Theatre Commercials Conflicts available upon request. Training Improv Comedy Upright Citizens Brigade: Matt Besser, Matt Walsh, Ian Roberts, Andy Daly, Dannah Feinglass, Seth Morris IO West: Derek Miller, Dave Hill On-Camera Margie Haber Studios: Saxon Trainor, Annie Grindlay Acting Risa Bramon-Garcia Commercial Khristopher Kyer, Jill Alexander Political Musical Theatre San Francisco Mime Troupe Workshop B.A. -

Ben Zelevansky Sag-Aftra

BEN ZELEVANSKY SAG-AFTRA TELEVISION THE GOLDBERGS Recurring ABC MODERN FAMILY Co-Star ABC BROOKLYN NINE-NINE Co-Star FOX THE PEOPLE vs OJ SIMPSON Co-Star F/X SHAMELESS Co-Star Showtime SCANDAL Co-Star ABC SILICON VALLEY Recurring HBO CASUAL Co-Star Hulu REAL ROB Guest Star Netflix IDIOTSITTER Co-Star Comedy Central FRESH OFF THE BOAT Co-Star ABC THE MIDDLE Guest Star ABC TRUE BLOOD Recurring HBO DON’T TRUST THE B—IN APT. 23 Recurring ABC NEW GIRL Co-Star FOX LOPEZ Co-Star TV Land HENRY DANGER Co-Star Nickelodeon EPISODES Co-Star Showtime BREAKING IN Recurring FOX COMMUNITY Co-Star NBC PARKS AND RECREATION Co-Star NBC FILM DEAD WOMEN WALKING Supporting Dir. Hagar Ben-Asher/blackpills THE BORDER Supporting Dir. Jordan Blum/Independent SUPER ZERO Lead Dir. Brandon Hall/USC Grad Film EXPIRATION DATE Supporting Dir. Jacob Strick/USC Grad Film MICHELE Supporting Dir. Amara Cash/Independent 7 COUCHES Supporting Dir. Chris Connolly/Independent INTERNET BAD SHORTS Series Regular Lucky Birds Media DISILLUSIONED Series Regular Shilpi Roy BUNNY AND BEE Series Regular Lucky Bird Media DUH-TECTIVE STORIES Series Regular Kids At Play Media ONION NEWS NETWORK Co-Star The Onion THE ONION RADIO NEWS Recurring The Onion TRAINING THE GROUNDLINGS – IMPROV JIMMY FOWLIE/PATTY GUGGENEHIM, COLLEEN SMITH, ROY JENKINS THE GROUNDLINGS – WRITING LAB LISA SCHURGA UPRIGHT CITIZENS BRIGADE – IMPROV/SKETCH WRITING AMY POEHLER, MATT BESSER, TIM KALPAKIS ON-CAMERA CLASSES – AUDITION INTENSIVE CHRISTINNA CHAUNCEY SPECIAL SKILLS Improvisation, comedy writing, voiceover, teleprompter, drums. DIALECTS: Southern, Boston, Chicago, British, Irish, Scottish, German, Australian AGENT: Brianna Ancel/Scot Reynolds / Phone: 818-509-0121 / Fax: 818-509-7729 10950 Ventura Blvd, Studio City, CA 91604 / [email protected] / [email protected] . -

Law Tarello - Entertainment Industry Professional

Law Tarello - Entertainment Industry Professional RÉSUMÉ HIGHLIGHTS & RELATED EXPERIENCE BROADWAY 25th Annual Putnam Spelling Bee Lead William Barfeé Circle in the Square OFF-BROADWAY Mortified: Angst Written Lead Self Magnet Theater, NY FILM & TELEVISION Hero of the Underworld Lucas Supporting Film Trick Candle Prod M’larky Manetti Supporting TV Pilot Comedy Central 4 Kings Barry Contract Lead TV Series NBC/Warner Bros The 4th Floor (Sketch Comedy) Lead Cast/Writer Web Series ComedyNet The Today Show Self Featured Interview NBC/Universal The Fantastic Four The Thing Commercial VO National TV Marvel Studios Home Depot Principal National Commercial Campaign Wee Beastie Prod Motorola/Comcast/NFL Principal National TV Commercial Comcast RADIO United Stations Radio Networks On-Air Comedy Performer/Personality USRN Air America Sketch/Interstitial Performer & Writer Green Family Media Road Runner Webmail VO - National Radio Time Warner The Olive Garden VO - National Radio Campaign M3 Productions Pepsi / Taco Bell National Radio/TV – VO M3 Productions IMPROVISATION Search Engine Improv (SEI) Co-Founder/Performer/ Instructor The Space, Rochester Fall Back Comedy Fest Creator/Executive Producer The Space, Rochester Boston Improv Festival Performer Improv Boston, MA Lazy Susan, Second Becky (SEI Originals) Performer Thumbs Upstate, Syracuse Providence Improv Festival Featured Performer Perishable Theater, RI MONSTROSITY Co-Creator /Performer The Space, Rochester Paul & Vinny Automotive (Improv sit-com) Co-Creator /Performer U.S. East Region Tour Chicago Improv Festival (CIF) Performer The Second City, Chicago Chicago Improv Festival Performer iO, Chicago IMPROV TRAINING Dave Pasquesi, T.J. Jagadowski, Dr. Martin De Maat The Second City Matt Besser, Amy Poehler, Ian Roberts, Matt Walsh Upright Citizens Brigade COLLEGE MFA-Interdisciplinary Arts Goddard College – Plainfield, VT 2015 B.A. -

Funny Feminism: Reading the Texts and Performances of Viola

FUNNY FEMINISM: READING THE TEXTS AND PERFORMANCES OF VIOLA SPOLIN, TINA FEY AND AMY POEHLER, AND AMY SCHUMER A Thesis by LYDIA KATHLEEN ABELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, James Ball Kristan Poirot Head of Department, Donnalee Dox May 2016 Major Subject: Performance Studies Copyright 2016 Lydia Kathleen Abell ABSTRACT This study examines the feminism of Viola Spolin, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, and Amy Schumer, all of whom, in some capacity, are involved in the contemporary practice and performance of feminist comedy. Using various feminist texts as tools, the author contextually and theoretically situates the women within particular feminist ideologies, reading their texts, representations, and performances as nuanced feminist assertions. Building upon her own experiences and sensations of being a fan, the author theorizes these comedic practitioners in relation to their audiences, their fans, influencing the ways in which young feminist relate to themselves, each other, their mentors, and their role models. Their articulations, in other words, affect the ways feminism is contemporarily conceived, and sometimes, humorously and contentiously advocated. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would briefly like to thank my family, especially my mother for her unwavering support during this difficult and stressful process. Her encouragement and happiness, as always, makes everything worth doing. I would also like to thank Paul Mindup for allowing me to talk through my entire thesis with him over the phone; somehow you listening diligently and silently on the other end of the line helped everything fall into place. -

PDF Download

Ben Zelevansky SAG-AFTRA Film Dead Women Walking Supporting blackpills The Border Supporting Ind/ Dir. Jordan Blum Super Zero Lead USC Grad/ Dir. Brandon Hall Expiration Date Supporting USC Grad/ Dir. Jacob Strick Michele Supporting Ind/ Dir. Amara Cash Television (selected) The Goldbergs Recurring ABC Schooled Recurring ABC Bosch Co-Star Amazon Modern Family Co-Star ABC Brooklyn Nine-Nine Co-Star Fox The People v. OJ Simpson Co-Star FX Silicon Valley Recurring HBO Scandal Co-Star ABC Shameless Co-Star Showtime Casual Co-Star Hulu The Middle Guest Star ABC Fresh off the Boat Co-Star ABC Real Rob Guest Star Netflix New Girl Co-Star Fox True Blood Recurring HBO Don’t Trust the B—in Apt. 23 Recurring ABC Breaking In Recurring Fox Parks and Recreation Co-Star NBC Internet Bad Shorts Series Regular Lucky Birds Media Disillusioned Series Regular Ind/ Dir. Shilpi Roy Duh-Tective Stories Series Regular Kids at Play Onion News Network Co-Star The Onion The Onion Radio News Recurring The Onion Training Upright Citizens Brigade (Improv) Amy Poehler, Matt Besser, Armando Diaz et al Upright Citizens Brigade (Sketch) Tim Kalpakis, Dan Gregor The Groundlings (Improv) Jimmy Fowlie/Patty Guggenheim, Roy Jenkins et al The Groundlings (Writing Lab) Lisa Schurga Special Skills Improvisation, comedy writing, voiceover, teleprompter, drums. DIALECTS: Southern, Boston, Chicago, British, Irish, Scottish, German, Australian 9000 Sunset Blvd. Suite 700, Los Angeles, CA 90069 P (310) 859-8889 . -

Ele Woods Sag, Aea-E

ELE WOODS SAG, AEA-E Seeking Representation Hair: Brown Eyes: Green/Hazel _______________________________________________________________________________________ FILM Unlovable Supporting Director, Suzi Yoonessi Rivergreaser Lead Director, Nick Rasmussen TELEVISION Brews Brothers Guest Star Director, Rob Cohen/Netflix American Princess Recurring Director, Various/ Lifetime Jimmy Kimmel Live Day Player Director, Various/ABC Still Laugh-In Featured Performer Various/ Netflix Will Vs. The Future Guest Star Director, Joe Nussbaum/Amazon The Good Place CoStar Director, Dean Holland/NBC Adam Ruins Everything CoStar Director, Matthew Pollack/TruTV The 2016 MTV Movie Awards Featured Performer Director, Glenn Weiss/MTV NEW MEDIA You and Your Best Friend Star Director, Michael Shaubauch, Snapchat Turnt Up With the Taylors Series Regular Director, Danny Daneau/ Facebook Do You Want to See a Dead BodyGuest Star Director, Nicolas Jasenovec/YoutubeRed Hot Tipz w/ Chris Kattan Day Player Director, Fax Bahr/FunnyorDie CollegeHumor Day Player Director, Various/CollegeHumor Drive Share Guest Star Director, Paul Scheer & Rob Huebel/VGo90 Take My Wife Recurring Dir. Sam Zwiebleman & Ingrid Jungermann UCB Show Day Player Director, Matt Besser/ Seeso THEATRE Maude Night House Team Performer Upright Citizen’s Brigade, Los Angeles Bachelor the Musical Lauren M Various, Los Angeles Victory! Nell Gwynn Atlantic Theatre, New York City Hairspray Velma VonTussle Town Hall Theatre, VT TRAINING Independent Shakespeare Company of Los Angeles - Ongoing training, Joseph Culliton Upright Citizens Brigade - Since 2008: Advanced Study Program, Diversity Program alumni. The Groundlings -Annie Sertich, Jordan Black (Advanced Lab) BA in Theatre from Middlebury College Clowning - Cirque Troc, Reignier France. SPECIAL SKILLS Improv, Var. Dance, Clowning, Roller skating/blading, Dodgeball, Snowboarding, Basketball, Soprano/Alto, Stage combat trained. -

Kat Burns Resume

kathryn burns choreographer selected credits contact: 818 509-0121 < FILM > Ibiza Dir. Alex Richanbach/ Prod. Will Ferrell, Adam McKay Under the Silver Lake Dir. David Robert Mitchell Wet Hot American Summer (Prequel) Netflix / Dir. David Wain Other People (Sundance 2016) Chris Kelly, Adam Scott Freak Dance with Amy Poehler Don’t Think Productions / Dir. Matt Besser The Future Roadside Attractions / Dir. Miranda July Love At The Christmas Table Lifetime TV / Dir. Rachel Goldenberg Escape from Polygamy Lifetime TV / Dir. Rachel Goldenberg High Road Dir. Matt Besser < TELEVISION > Crazy Ex Girlfriend (Show choreographer) CW Black Monday (multiple episodes) Showtime E! Funny Dance Show E! First Wives Club BET Drunk History (multiple episodes) Comedy Central Splitting Up Together ABC American Princess Lifetime TV Future Man Hulu Happy Together- Flash Mob CBS The Other Two Comedy Central After Rap (multiple episodes) ABC Angie Tribeca TBS Lucifer Netflix/ Fox Let’s Get Physical Pop SMILF Showtime Great News (season 2) NBC Better Things (season 2) FX Logic-Jimmy Kimmel Live ABC Walk the Prank (multiple episodes) Disney XD/Disney Channel Throwing Shade Viacom Bill Nye Saves the World Bunim/Murray Productions The Late Late Show with James Corden CBS Broadcasting, Inc. Michael Bolton’s Big, Sexy Valentine’s Day CBB Productions, INC. Workaholics 50/50 Productions Odd Couple ABC Wet Hot American Summer American Summer Productions, Inc. Teachers (multiple episodes) TV Land/ Teachers c/o Hudson Street Productions One Mississippi (multiple episodes) Amazon Video Loosely Exactly Nicole Dir. Linda Mendoza Stuck in the Middle (multiple episodes) Horizon Productions Inc. Key & Peele (9 episodes) Comedy Central / Dir. -

A Look at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and Hidden Collections of Improv Comedy

Never Done Before, Never Seen Again: A Look at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and Hidden Collections of Improv Comedy By Caroline Roll A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program Department of Cinema Studies New York University May 2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Chapter 1: A History of Improv Comedy ...……………………………………………………... 5 Chapter 2: Improv in Film and Television ...…………………………………………………… 20 Chapter 3: Case Studies: The Second City, The Groundlings, and iO Chicago ...……………... 28 Chapter 4: Assessment of the UCB Collection ……………..………………………………….. 36 5: Recommendations ………..………………………………………………………………….. 52 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………... 57 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………… 60 Acknowledgements …...………………………………………………………………………... 64 2 Introduction All forms of live performance have a certain measure of ephemerality, but no form is more fleeting than an improvised performance, which is conceived in the moment and then never performed again. The most popular contemporary form of improvised performance is improv comedy, which maintains a philosophy that is deeply entrenched in the idea that a show only happens once. The history, principles, and techniques of improv are well documented in texts and in moving images. There are guides on how to improvise, articles and books on its development and cultural impact, and footage of comedians discussing improv in interviews and documentaries. Yet recordings of improv performances are much less prevalent, despite the fact that they could have significant educational, historical, or entertainment value. Unfortunately, improv theatres are concentrated in major cities, and people who live outside of those areas lack access to improv shows. This limits the scope for researchers as well.