Native American Stereotyping in Peter Pan: a Modern Solution?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indigenous Body As Animated Palimpsest Michelle Johnson Phd Candidate, Dance Studies | York University, Toronto, Canada

CONTINGENT HORIZONS The York University Student Journal of Anthropology VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 (2019) OBJECTS “Not That You’re a Savage” The Indigenous Body as Animated Palimpsest Michelle Johnson PhD candidate, Dance Studies | York University, Toronto, Canada Contingent Horizons: The York University Student Journal of Anthropology. 2019. 5(1):45–62. First published online July 12, 2019. Contingent Horizons is available online at ch.journals.yorku.ca. Contingent Horizons is an annual open-access, peer-reviewed student journal published by the department of anthropology at York University, Toronto, Canada. The journal provides a platform for graduate and undergraduate students of anthropology to publish their outstanding scholarly work in a peer-reviewed academic forum. Contingent Horizons is run by a student editorial collective and is guided by an ethos of social justice, which informs its functioning, structure, and policies. Contingent Horizons’ website provides open-access to the journal’s published articles. ISSN 2292-7514 (Print) ISSN 2292-6739 (Online) editorial collective Meredith Evans, Nadine Ryan, Isabella Chawrun, Divy Puvimanasinghe, and Katie Squires cover photo Jordan Hodgins “Not That You’re a Savage” The Indigenous Body as Animated Palimpsest MICHELLE JOHNSON PHD CANDIDATE, DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, CANADA In 1995, Disney Studios released Pocahontas, its first animated feature based on a historical figure and featuring Indigenous characters. Amongst mixed reviews, the film provoked criti- cism regarding historical inaccuracy, cultural disrespect, and the sexualization of the titular Pocahontas as a Native American woman. Over the following years the studio has released a handful of films centered around Indigenous cultures, rooted in varying degrees of reality and fantasy. -

Peter Pan Education Pack

PETER PAN EDUCATION PACK Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Peter Pan: A Short Synopsis ....................................................................................................... 4 About the Writer ....................................................................................................................... 5 The Characters ........................................................................................................................... 7 Meet the Cast ............................................................................................................................ 9 The Theatre Company ............................................................................................................. 12 Who Would You Like To Be? ................................................................................................... 14 Be an Actor .............................................................................................................................. 15 Be a Playwright ........................................................................................................................ 18 Be a Set Designer ..................................................................................................................... 22 Draw the Set ............................................................................................................................ 24 Costume -

Hiff and Bafta New York to Honor Bevan and Fellner of Working Title Films With

THE HAMPTONS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS, NEW YORK HONORS WORKING TITLE FILMS CO-CHAIRS - TIM BEVAN AND ERIC FELLNER WITH THE GOLDEN STARFISH AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AS PART OF THE FESTIVAL’S “FOCUS ON UK FILM.” BAFTA and Academy® Award Winner Renée Zellweger Will Introduce the Honorees and be joined by Richard Curtis, Joe Wright and Edgar Wright to toast the Producers. East Hampton, NY (September 17, 2013) - The Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF) and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts New York (BAFTA New York), announced today that they will present Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner, co-chairs of British production powerhouse Working Title Films, with this year’s Golden Starfish Award for Lifetime Achievement on October 12th during the festival. Actress, Renée Zellweger, who came to prominence as the star of Working Title Films’ Bridget Jones’ Diary movies, will introduce the event. Working Title Films has produced some of the most well known films from the UK including LES MISERABLES, ATONEMENT, FOUR WEDDINGS AND A FUNERAL, ELIZABETH, and BILLY ELLIOT to name just a few. Richard Curtis (ABOUT TIME, LOVE ACTUALLY), Edgar Wright (THE WORLD'S END, SHAUN OF THE DEAD) and Joe Wright (ANNA KARENINA, ATONEMENT), three directors and longtime collaborators responsible for some of Working Title Films most acclaimed titles, will join Renee Zellweger, Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner in conversation for an insider’s view of Working Title Films. “The Hamptons International Film Festival is pleased to recognize Working Title Films and its incredible body of work,” said Anne Chaisson, Executive Director of The Hamptons International Film Festival. -

DOCUMENT RESUME RC 021 689 AUTHOR Many Nations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 046 RC 021 689 AUTHOR Frazier, Patrick, Ed. TITLE Many Nations: A Library of Congress Resource Guide for the Study of Indian and Alaska Native Peoples of the United States. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-8444-0904-9 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 357p.; Photographs and illustrations may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom (055) -- Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alaska Natives; American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; American Indian Languages; *American Indian Studies; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Federal Indian Relationship; *Library Collections; *Resource Materials; Tribes; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT The Library of Congress has a wealth of information on North American Indian people but does not have a separate collection or section devoted to them. The nature of the Librarv's broad subject divisions, variety of formats, and methods of acquisition have dispersed relevant material among a number of divisions. This guide aims to help the researcher to encounter Indian people through the Library's collections and to enhance the Library staff's own ability to assist with that encounter. The guide is arranged by collections or divisions within the Library and focuses on American Indian and Alaska Native peoples within the United States. Each -

Racial Literacy Curriculum Parent/Guardian Companion Guide

Pollyanna Racial Literacy Curriculum PARENT/GUARDIAN COMPANION GUIDE ©2019 Pollyanna, Inc. – Parent/Guardian Companion Guide | Monique Vogelsang, Primary Contributor CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Why is important to learn about and discuss race? 1 What is the Racial Literacy Curriculum? 1 How is the Curriculum Structured? 2 What is the Parent/Guardian Companion Guide? 2 How is the Companion Guide Structured? 3 Quick Notes About Terminology 3 UNITS The Physical World Around Us 5 A Celebration of (Skin) Colors We Are Part of a Larger Community 9 Encouraging Kindness, Social Awareness, and Empathy Diversity Around the World 13 How Geography and Our Daily Lives Connect Us Stories of Activism 17 How One Voice Can Change a Community (and Bridge the World) The Development of Civilization 24 How Geography Gave Some Populations a Head Start (Dispelling Myths of Racial Superiority) How “Immigration” Shaped the Racial and 29 Cultural Landscape of the United States The Persecution, Resistance, and Contributions of Immigrants and Enslaved People The Historical Construction of Race and 36 Current Racial Identities Throughout U.S. Society The Danger of a Single Story What is Race? 48 How Science, Society, and the Media (Mis)represent Race Please note: This document is strictly private, confidential Race as Primary “Institution” of the U.S. 55 and should not be copied, distributed or reproduced in How We May Combat Systemic Inequality whole or in part, nor passed to any third party outside of your school’s parents/guardians, without the prior consent of Pollyanna. PAGE ii ©2019 Pollyanna, Inc. – Parent/Guardian Companion Guide | Monique Vogelsang, Primary Contributor INTRODUCTION Why is it important to learn about and discuss race? Educators, sociologists, and psychologists recommend that we address concepts of race and racism with our children as soon as possible. -

Study Guide for Educators

Study Guide for Educators A Musical Based on the Play by Sir James M. Barrie Music by Mark Charlap Additional Music by Jule Styne Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh Additional Lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green Originally Adapted and Directed by Jerome Robbins 1 This production of Peter Pan is generously sponsored by: Ng & Ng Dental and Eye Care Joan Gellert-Sargen Jerry & Sharon Melson Ron Tindall, RN Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. -

Whitewashing Or Amnesia: a Study of the Construction

WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES A DISSERTATION IN Sociology and History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by DEBRA KAY TAYLOR M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2005 B.L.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2000 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 DEBRA KAY TAYLOR ALL RIGHTS RESERVE WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES Debra Kay Taylor, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT This inter-disciplinary dissertation utilizes sociological and historical research methods for a critical comparative analysis of the material culture as reproduced through murals and monuments located in two counties in Missouri, Bates County and Cass County. Employing Critical Race Theory as the theoretical framework, each counties’ analysis results are examined. The concepts of race, systemic racism, White privilege and interest-convergence are used to assess both counties continuance of sustaining a racially imbalanced historical narrative. I posit that the construction of history of Bates County and Cass County continues to influence and reinforces systemic racism in the local narrative. Keywords: critical race theory, race, racism, social construction of reality, white privilege, normality, interest-convergence iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, have examined a dissertation titled, “Whitewashing or Amnesia: A Study of the Construction of Race in Two Midwestern Counties,” presented by Debra Kay Taylor, candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

Beyond Race, Within Media: How Third Culture Audiences Engage with Whitewashed Films of a Japanese Origin

BEYOND RACE, WITHIN MEDIA Beyond Race, Within Media: How Third Culture Audiences Engage with Whitewashed Films of a Japanese Origin Annette Kari Ydia Medalla A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree BA (Hons) Communication and Media School of Media and Communication, University of Leeds May 2018 Word Count: 12,000 !1 BEYOND RACE, WITHIN MEDIA Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 5 Literature Review 7 Media engagement in migrant communities 7 Different and the same: overlapping identities 9 Whitewashing and its implications 11 Whitewashing in the context of global flow 12 Japan: a contra flow to the Western global flow 13 A matter of race and Orientalism 14 Research Design 17 Methodological Approach 17 Sampling Technique 18 Research Tool 19 Findings 22 Consuming media as a third culture kid 22 Remembering or rejecting: sifting through various cultural values 23 A world-view shaped by the third culture experience 25 The TCK experience as grounds for empathy and sensitivity 25 Common interests and connections 26 How relocating to the West breeds a more insightful understanding of race 27 A different perspective: assimilation and apathy towards race in media 28 ‘It really doesn’t matter’: an apathetic approach to whitewashing 28 Inconsistencies and gendered implications 31 A vehement rejection of whitewashing: negative experiences and high media consumption 32 Rejection informed by negative third culture experiences 32 Rejection informed by high media consumption 33 Moving forward: away from the West and towards a third culture 34 Conclusion 36 Summary of findings 36 Contribution to scholarship and future research 38 Bibliography 40 Appendix A 44 Appendix B 45 Appendix C 47 Appendix D 49 Appendix E 64 !2 BEYOND RACE, WITHIN MEDIA Abstract Third culture kids (TCKs) are among the fastest growing population of multiracial individuals as well as part of a global migrant community. -

Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller

Literature to Film, lecture on Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller Atonement (2007) Universal Pictures Director: Joe Wright Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton Novel: Ian McEwan 123 minutes Cast Cecilia Tallis Keira Knightley Robbie Turner James McAvoy Briony Tallis,Briony Romola Garai Older Briony Vanessa Redgrave Briony Taliis,Briony Saoirse Ronan Grace Turner Brenda Blethyn Singing Housemaid Allie MacKay Betty Julia Ann West Lola Quincey Juno Temple Jackson Quincey Charlie Von Simpson Leon Tallis Patrick Kennedy Paul Marshall Benedict Cumberbatch Emily Tallis Harriet Walter Fiona MacGuire Michelle Duncan Sister Drummond Gina McKee Police Constable Leander Deeny Luc Cornet Jeremie Renier Police Sergeant Peter McNeil O’Connor Tommy Nettle Daniel Mays Danny Hardman Alfie Allen Pierrot,Pierrot Jack Harcourt Frenchmen Michel Vuillemoz Jackson,Jackson Ben Harcourt Frenchmen Lionel Abelanski Frank Mace Nonso Anozie Naval Officer Tobias Menzies Crying Soldier Paul Stocker Police Inspector Peter Wright Solitary Sunbather Alex Noodle Vicar John Normington Mrs. Jarvis Wendy Nottingham Beach Soldier Roger Evans, Bronson Webb, Ian Bonar, Oliver Gilbert Interviewer Anthony Minghella Soldier in Bray Bar Jamie Beamish, Johnny Harris, Nick Bagnall, Billy Seymour, Neil Maskell Soldier With Ukulele Paul Harper Probationary Nurse Charlie Banks, Madeleine Crowe, Olivia Grant, Scarlett Dalton, Katy Lawrence, Jade Moulla, Georgia Oakley, Alice Orr-Ewing, Catherine Philps, Bryony Reiss, DSarah Shaul, Anna Singleton, Emily Thomson Hospital Admin Assistant Kelly Scott Soldier at Hospital Entrance Mark Holgate Registrar Ryan Kiggell Staff Nurse Vivienne Gibbs Second Soldier at Hospital Entrance Matthew Forest Injured Sergeant Richard Stacey Soldier Who Looks Like Robbie Jay Quinn Mother of Evacuees Tilly Vosburgh Evacuee Child Angel Witney, Bonnie Witney, Webb Bem 1 Primary source director’s commentary by Joe Wright. -

Edward Said's Orientalism

Arcadia University Edward Said’s Orientalism: Trapped in Time Samantha Lori Glass Dr. Holderman & Professor Powell Senior Seminar II CM490 15 April 2020 Glass 1 “Orientalism” Edward Said’s theory, Orientalism, was written in 1978. Said’s argument focused on the treatment of what is considered as “The East.” In his introduction, Said states that the European concept of the orient is the Far East, which includes Japan and China, while the American notion is known as the Middle East (Said 1-2). This specificity on the area is representative of the history of Europe versus the United States. His main criticism lies in the idea that Western cultures negatively view and represent Eastern cultures. The West has been able to belittle the East through the power that these cultures have acquired. This disparage presents negative images of the different Eastern cultures, which is used as a mechanism to make the West more powerful. This, in turn, has created the idea of the Other. The irony of this entire concept is that the West has been dependent on the East, therefore to create this disparity is a power play. This dependency has not only been for land, but also for raw materials. Orientalism has been a very successful way for Western cultures to gain power. Furthermore, art has been a way to represent the cultures of the East. However, many of the representations have been created by the West and are used to create stereotypical images of multiple cultures (Said 21). Said organizes Orientalism by looking at three main concepts. -

Ian Mcewan's Atonement

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka ANETA VRÁGOVÁ III. ročník – prezenční studium Obor: Anglický jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání – Německý jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání IAN MCEWAN’S ATONEMENT: COMPARISON OF THE NOVEL AND THE FILM ADAPTATION Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Josef Nevařil, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci vypracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci (datum) ……………………………………………… vlastnoruční podpis I would like to thank Mgr. Josef Nevařil, Ph. D. for his assistance, comments and guidance throughout the writing process. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 6 1. BIOGRAPHY OF IAN MCEWAN ...................................................................... 7 1.1. BIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................... 7 1.2. LITERARY OUTPUT ...................................................................................... 8 1.3. AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS ................................................................ 9 2. POSTMODERNISM .......................................................................................... 12 3. COMPARISON OF THE NOVEL ATONEMENT AND THE FILM ADAPTATION ......................................................................................................................... 14 3.1. NOVEL: GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ -

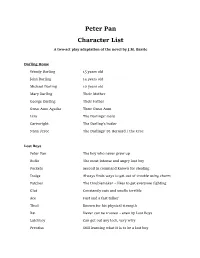

Peter Pan Character List

Peter Pan Character List A two-act play adaptation of the novel by J.M. Barrie Darling Home Wendy Darling 15 years old John Darling 14 years old Michael Darling 10 years old Mary Darling Their Mother George Darling Their Father Great Aunt Agatha Their Great Aunt Liza The Darlings’ maid Cartwright The Darling’s butler Nana /Croc The Darlings’ St. Bernard / the Croc Lost Boys Peter Pan The boy who never grew up Rufio The most intense and angry lost boy Pockets Second in command known for stealing Dodge Always finds ways to get out of trouble using charm Patches The troublemaker – likes to get everyone fighting Glut Constantly eats and smells terrible Ace Fast and a fast talker Thud Known for his physical strength Rat Never can be trusted – even by Lost Boys Latchboy Can get out any lock, very wiry Prentiss Still learning what it is to be a lost boy Curly Not very smart but very loveable James Tries to use reason – which no one listens to. Danny Taken with Glut – very smart – no one listens to him Laddie Ends up getting taken with Glut, scared of everything The Pirates Captain Hook The Captain Smee Captain Cook’s loyal assistant Gentleman Starkey The First Mate – does not tolerate anything Robert Mullins The Ships Gunner Billy Jukes Youngest pirate Hector Is grumpy all of the time Cecco A pirate of Italian Descent Mr. Holiday Loves his mustache – vain Alf Lazy –hates being a pirate Morgan More of a Dandy than a Pirate Cookson The worst cook Chay Loves everything about being a Pirate Hawkins The Doctor Bellamy His brother is a lost boy – very conflicted Norrington Wants to get rid of Hook and take over The Tribe Tiger Lily The Chiefs daughter Mano The Chief and father of Tiger Lily Lea The Mother of Tiger Lily Kona The Old Mother of the Chief – very set in her ways Kalani Is a true fighter, yet never given the chance Loni Best at the bow - also wants to be a fighter Kalena Mean.