Policy on the Use of Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probable Cause for Arrest in Indiana: a Prosecutor Hoist with His Own Kinnaird

Indiana Law Journal Volume 45 Issue 1 Article 3 Fall 1969 Probable Cause for Arrest in Indiana: A Prosecutor Hoist With His Own Kinnaird F. Thomas Schornhorst Indiana University Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Schornhorst, F. Thomas (1969) "Probable Cause for Arrest in Indiana: A Prosecutor Hoist With His Own Kinnaird," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 45 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol45/iss1/3 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PROBABLE CAUSE FOR ARREST IN INDIANA: A PROSECUTOR HOIST WITH HIS OWN KINNAIRD F. THOMAS SCHORNHORSTt For'tis the sport to have the enginer Hoist with his own petar.... HAmtLET, ACT III, SCENE IV A judicial decision that an arrest warrant must be supported by an affidavit alleging facts and circumstances sufficient to justify a magist- rate's finding of probable cause in order to make lawful an arrest and incidental search based on that warrant would not seem worthy of law journal commentary in 1969. One would think that this issue had been settled in the stormy period following Mapp v. Ohio" in Ker v. Cali- fornia,' Beck v. Ohio,' Wong Sun v. United States4 and Aguilar v. -

Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 2016

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics October 2019, NCJ 251922 Bureau of Justice Statistics Bureau Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 – Statistical Tables Connor Brooks, BJS Statistician s of the end of fscal-year 2016, federal FIGURE 1 agencies in the United States and Distribution of full-time federal law enforcement U.S. territories employed about 132,000 ofcers, by department or branch, 2016 Afull-time law enforcement ofcers. Federal law enforcement ofcers were defned as any federal Department of ofcers who were authorized to make arrests Homeland Security and carry frearms. About three-quarters of Department of Justice federal law enforcement ofcers (about 100,000) Other executive- provided police protection as their primary branch agencies function. Four in fve federal law enforcement ofcers, regardless of their primary function, Independent agencies worked for either the Department of Homeland · Security (47% of all ofcers) or the Department Judicial branch Tables Statistical of Justice (33%) (fgure 1, table 1). Legislative branch Findings in this report are from the 2016 0 10 20 30 40 50 Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers Percent (CFLEO). Te Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted the census, collecting data on Note: See table 1 for counts and percentages. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law 83 agencies. Of these agencies, 41 were Ofces Enforcement Ofcers, 2016. of Inspectors General, which provide oversight of federal agencies and activities. Te tables in this report provide statistics on the number, functions, and demographics of federal law enforcement ofcers. Highlights In 2016, there were about 100,000 full-time Between 2008 and 2016, the Amtrak Police federal law enforcement ofcers in the United had the largest percentage increase in full-time States and U.S. -

Use of Force

Policy Tualatin Police Department ••• Policy Manual Use of Force 300.1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE This policy recognizes that the use of force by law enforcement requires constant evaluation. Even at its lowest level, the use of force is a serious responsibility. The purpose of this policy is to provide officers of this department with guidelines on the reasonable use of force. While there is no way to specify the exact amount or type of reasonable force to be applied in any situation, each officer is expected to use these guidelines to make such decisions in a professional, impartial and reasonable manner. 300.1.1 PHILOSOPHY The use of force by law enforcement personnel is a matter of critical concern both to the public and to the law enforcement community. Officers are involved on a daily basis in numerous and varied human encounters and when warranted, may use force in carrying out their duties. Officers must have an understanding of, and true appreciation for, the limitations of their authority. This is especially true with respect to officers overcoming resistance while engaged in the performance of their duties. The Department recognizes and respects the value of all human life and dignity without prejudice to anyone. It is also understood that vesting officers with the authority to use reasonable force and protect the public welfare requires a careful balancing of all human interests. 300.1.2 DUTY TO INTERCEDE Any officer present and observing another officer using force that is clearly beyond that which is objectively reasonable under the circumstances shall, when in a position to do so, intercede to prevent the use of such excessive force. -

Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures Under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 78 Article 3 Issue 4 Winter Winter 1988 Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Elsie Romero, Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine, 78 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 763 (1987-1988) This Supreme Court Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/88/7804-763 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAw & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 78, No. 4 Copyright @ 1988 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. FOURTH AMENDMENT-REQUIRING PROBABLE CAUSE FOR SEARCHES AND SEIZURES UNDER THE PLAIN VIEW DOCTRINE Arizona v. Hicks, 107 S. Ct. 1149 (1987). I. INTRODUCTION The fourth amendment to the United States Constitution pro- tects individuals against arbitrary and unreasonable searches and seizures. 1 Fourth amendment protection has repeatedly been found to include a general requirement of a warrant based on probable cause for any search or seizure by a law enforcement agent.2 How- ever, there exist a limited number of "specifically established and -

Drawing a Line Between Terry and Miranda: the Degree and Duration of Restraint Katherine M

Drawing a Line between Terry and Miranda: The Degree and Duration of Restraint Katherine M. Swifit INTRODUCTION A felon answered the door in his underwear. Three police officers and three parole officers were there to search his apartment for a gun on the basis of a tip from his mother.! The police handcuffed him in the hallway outside his apartment, but told him he was not under ar- rest; the handcuffs were for his safety and the safety of the officers. Then they took him inside and asked about the gun, which he told them was in a shoebox on the table. The police never read the suspect his Miranda warnings. Was he "in custody"? Or was this merely a tem- porary detention? Mirandav Arizona' held that police may not interrogate a suspect who has been taken into custody without first issuing the familiar warnings Investigative stops, valid under Terry v Ohio,' are not sub- ject to Miranda's notice requirements.! Courts have not settled on a workable rule for determining custody in Terry stop cases. Part of the problem is that custody cases involve so many factors.! But more im- portant, coercive police behavior that would have required Miranda warnings in 1966 often is deemed reasonable under Terry today. This has led to a circuit split over whether coercive Terry stops constitute Miranda custody. The First, Fourth, and Eighth circuits hold t B.A., BJ. 1998, University of Missouri-Columbia; J.D. 2006, The University of Chicago. I The facts used in this example are drawn from United States v Newton, 369 F3d 659, 663 (2d Cir 2004). -

New Haven Department of Police Service General

GENERAL ORDER 5.01 Page 1 of 9 NEW HAVEN DEPARTMENT OF POLICE SERVICE GENERAL ORDERS GENERAL ORDER 5.01 EFFECTIVE DATE: June 6, 2016 5.01.01 PURPOSE The purpose of this General Order is to provide officers of the New Haven Department of Police Service with basic guidelines for conducting arrests. 5.01.02 POLICY It is the policy of the New Haven Department of Police Service that all arrests made by departmental personnel shall be conducted professionally and in accordance with established legal principles. In furtherance of this policy, all officers of this department are expected to be aware of, understand, and follow the laws governing arrest. This policy sets forth the fundamentals of the arrest procedure. 5.01.03 DEFINITIONS ARREST: Actual or constructive seizure or detention of a person, performed with the intention to effect an arrest and so understood by the person detained. ARREST WARRANT: A written order issued by a judge or other proper authority that commands a law enforcement officer to place a person under arrest. GENERAL ORDER &O1 Page 2 of 9 PROBABLE CAUSE FOR ARREST: The existence of circumstances that would lead a reasonably prudent person to believe that a crime was committed and the individual to be arrested has committed the crime. REASONABLE SUSPICION: The existence of circumstances that would lead a reasonable police officer to believe that an individual is engaging in criminal activity. INVESTIGATIVE DETENTION (“TERRY STOP”): Temporary detention for investigative purposes of a person based upon reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime, under circumstances that do not amount to probable cause for arrest. -

Informer January 2017

Department of Homeland Security Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers Office of Chief Counsel Legal Training Division January 2017 THE FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT -INFORMER- A MONTHLY LEGAL RESOURCE AND COMMENTARY FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS AND AGENTS Welcome to this installment of The Federal Law Enforcement Informer (The Informer). The Legal Training Division of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers’ Office of Chief Counsel is dedicated to providing law enforcement officers with quality, useful and timely United States Supreme Court and federal Circuit Courts of Appeals reviews, interesting developments in the law, and legal articles written to clarify or highlight various issues. The views expressed in these articles are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers. The Informer is researched and written by members of the Legal Division. All comments, suggestions, or questions regarding The Informer can be directed to the Editor at (912) 267-3429 or [email protected]. You can join The Informer Mailing List, have The Informer delivered directly to you via e-mail, and view copies of the current and past editions and articles in The Quarterly Review and The Informer by visiting https://www.fletc.gov/legal-resources. This edition of The Informer may be cited as 1 INFORMER 17. Join THE INFORMER E-mail Subscription List It’s easy! Click HERE to subscribe, change your e-mail address, or unsubscribe. THIS IS A SECURE SERVICE. No one but the FLETC Legal Division will have access to your address, and you will receive mailings from no one except the FLETC Legal Division. -

Department and Agency Implementation Plans for the U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Department and Agency Implementation Plans for The U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security This page intentionally left blank. Department and Agency Implementation Plans for The U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Acting Secretary’s Forward..................................................................6 Introduction........................................................................................8 Department/Agency Approach..........................................................9 Lines of Effort (“LOE”).....................................................................10 LOE 1: Participation.................................................................10 LOE 2: Protection and Access..................................................10 LOE 3: Internal U.S. Capabilities.............................................11 LOE 4: Partner Support............................................................12 Process/Cross Cutting........................................................................13 Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning.............................................13 6 | Department of Homeland Security Acting Secretary’s Forward In 2017, President Donald J.Trump signed a frst of its kind law recognizing the essential role of women around the world in promoting peace, maintaining security, and preventing confict and abuse.The Women, Peace, and Security Act of 2017 (WPS Act) advances opportunities for women to participate in these efforts—both at home -

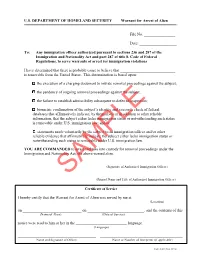

Warrant for Arrest of Alien

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY Warrant for Arrest of Alien File No. ________________ Date: ___________________ To: Any immigration officer authorized pursuant to sections 236 and 287 of the Immigration and Nationality Act and part 287 of title 8, Code of Federal Regulations, to serve warrants of arrest for immigration violations I have determined that there is probable cause to believe that ____________________________ is removable from the United States. This determination is based upon: the execution of a charging document to initiate removal proceedings against the subject; the pendency of ongoing removal proceedings against the subject; the failure to establish admissibility subsequent to deferred inspection; biometric confirmation of the subject’s identity and a records check of federal databases that affirmatively indicate, by themselves or in addition to other reliable information, that the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law; and/or statements made voluntarily by the subject to an immigration officer and/or other reliable evidence that affirmatively indicate the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law. YOU ARE COMMANDED to arrest and take into custody for removal proceedings under the Immigration and Nationality Act, the above-named alien. __________________________________________ (Signature of Authorized Immigration Officer) __________________________________________ SAMPLE (Printed Name and Title of Authorized Immigration Officer) Certificate of Service I hereby certify that the Warrant for Arrest of Alien was served by me at __________________________ (Location) on ______________________________ on _____________________________, and the contents of this (Name of Alien) (Date of Service) notice were read to him or her in the __________________________ language. -

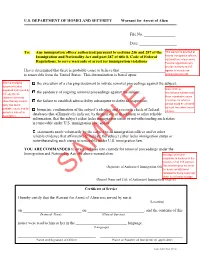

Ice Warrant of Arrest

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY Warrant for Arrest of Alien File No. ________________ Date: ___________________ To: Any immigration officer authorized pursuant to sections 236 and 287 of the Immigration and Nationality Act and part 287 of title 8, Code of Federal Regulations, to serve warrants of arrest for immigration violations I have determined that there is probable cause to believe that ____________________________ is removable from the United States. This determination is based upon: the execution of a charging document to initiate removal proceedings against the subject; the pendency of ongoing removal proceedings against the subject; the failure to establish admissibility subsequent to deferred inspection; biometric confirmation of the subject’s identity and a records check of federal databases that affirmatively indicate, by themselves or in addition to other reliable information, that the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law; and/or statements made voluntarily by the subject to an immigration officer and/or other reliable evidence that affirmatively indicate the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law. YOU ARE COMMANDED to arrest and take into custody for removal proceedings under the Immigration and Nationality Act, the above-named alien. __________________________________________ (Signature of Authorized Immigration Officer) __________________________________________ SAMPLE (Printed Name and Title of Authorized Immigration Officer) Certificate of Service I hereby certify that the Warrant for Arrest of Alien was served by me at __________________________ (Location) on ______________________________ on _____________________________, and the contents of this (Name of Alien) (Date of Service) notice were read to him or her in the __________________________ language. -

Officer's Use of Force: the Investigative Process

Officer’s Use of Force: The Investigative Process John Aldridge Assistant General Counsel North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association Post Office Box 20049 Raleigh, North Carolina 27619 (919) SHERIFF (743-7433) www.ncsheriffs.org September 2018 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Authority for an SBI Investigation .................................................................................................. 1 Scope and Limitations of Investigations .......................................................................................... 2 How to Initiate an SBI Investigation ............................................................................................... 4 What to Expect During an SBI Use of Force Investigation ................................................................. 5 What are the Potential Civil Liability Issues After a Use of Force Incident? ......................................... 8 Use of the Doctrine of Qualified Immunity .....................................................................................11 Should You Work an Officer Pending an Investigation? ...................................................................12 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................13 NC Sheriffs’ Association Officer’s Use of Force: The Investigative Process September 2018 Introduction Law enforcement officers -

Northern Virginia Criminal Justice Training Academy

Northern Virginia Criminal Justice Training Academy 1. Ban on chokeholds- All NVCJA member agencies currently forbid any and all types of chokeholds. To our knowledge, this has been the case for over 20 years. It makes perfect sense to suggest that use of a chokehold by police, when a lesser force option is available, could prevent death or serious injury. In a deadly force situation, an officer is permitted to use any weapon or technique, including a gun, a brick, a chokehold, or any other option to stop the threat to life presented by the perpetrator. Whether an officer is trained to use a chokehold technique is irrelevant when involved in a deadly force situation. Bottom line, when deadly force is justified by an officer, it does not matter what force is used or what type of weapon is used. It is the totality of the circumstances that decides reasonableness. Again, having said that, we do not teach any chokehold technique at the Academy. 2. Require de-escalation training- The NVCJA presently provides over 40 hours of classroom training in the areas of Interpersonal Communications, Bias awareness, interaction with specialty groups (Emotionally Disturbed, Autism, Deaf, Handicapped, etc.), community interaction, mitigation, negotiation, and ethics. It is stressed that the most powerful tool officers have is their ability to communicate. The various force options are to be utilized in conjunction with, not in place of, communication skills when the situation dictates the need for force to gain control. Control is obtained in order to allow for facilitation of a long-term remedy.