Contest and Exploitation of Achill Island's Historic Maritime Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4¼N5 E0 4¼N5 4¼N4 4¼N4 4¼N4 4¼N5

#] Mullaghmore \# Bundoran 0 20 km Classiebawn Castle V# Creevykeel e# 0 10 miles ä# Lough #\ Goort Cairn Melvin Cliffony Inishmurray 0¸N15 FERMANAGH LEITRIM Grange #\ Cashelgarran ATLANTIC Benwee Dun Ballyconnell#\ Benbulben #\ R(525m) Head #\ Portacloy Briste Lough Glencar OCEAN Carney #\ Downpatrick 1 Raghly #\ #\ Drumcliff # Lackan 4¼N16 Manorhamilton Erris Head Bay Lenadoon Broad Belderrig Sligo #\ Rosses Point #\ Head #\ Point Aughris Haven ä# Ballycastle Easkey Airport Magheraghanrush \# #\ Rossport #\ Head Bay Céide #\ Dromore #– Sligo #\ ä# Court Tomb Blacklion #\ 0¸R314 #4 \# Fields West Strandhill Pollatomish e #\ Lough Gill Doonamo Lackan Killala Kilglass #\ Carrowmore ä# #æ Point Belmullet r Bay 4¼N59 Innisfree Island CAVAN #\ o Strand Megalithic m Cemetery n #\ #\ R \# e #\ Enniscrone Ballysadare \# Dowra Carrowmore i Ballintogher w v #\ Lough Killala e O \# r Ballygawley r Slieve Gamph Collooney e 4¼N59 E v a (Ox Mountains) Blacksod i ä# skey 4¼N4 Lough Mullet Bay Bangor Erris #\ R Rosserk Allen 4¼N59 Dahybaun Inishkea Peninsula Abbey SLIGO Ballinacarrow#\ #\ #\ Riverstown Lough Aghleam#\ #\ Drumfin Crossmolina \# y #\ #\ Ballina o Bunnyconnellan M Ballymote #\ Castlebaldwin Blacksod er \# Ballcroy iv Carrowkeel #\ Lough R #5 Ballyfarnon National 4¼N4 #\ Conn 4¼N26 #\ Megalithic Cemetery 4¼N59 Park Castlehill Lough Tubbercurry #\ RNephin Beg Caves of Keash #8 Arrow Dugort #÷ Lahardane #\ (628m) #\ Ballinafad #\ #\ R Ballycroy Bricklieve Lough Mt Nephin 4¼N17 Gurteen #\ Mountains #\ Achill Key Leitrim #\ #3 Nephin Beg (806m) -

Redaction Version Schedule 2.3 (Deployment Requirements) 2.3

Redaction Version Schedule 2.3 (Deployment Requirements) 2.3 DEPLOYMENT REQUIREMENTS MHC-22673847-3 Redaction Version Schedule 2.3 (Deployment Requirements) 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Schedule sets out the deployment requirements. Its purpose is to set out the minimum requirements with which NBPco must comply with respect to the deployment of the Network. 2 SERVICE REQUIREMENTS 2.1 NBPco is required throughout the Contract Period to satisfy and comply with all the requirements and descriptions set out in, and all other aspects of, this Schedule. 3 GENERAL NBPCO OBLIGATIONS 3.1 Without limiting or affecting any other provision of this Agreement, in addition to its obligations set out in Clause 14 (Network Deployment, Operation and Maintenance) and the requirements for Network Deployment set out in Paragraph 8 (Network Deployment – Requirements) of this Schedule and elsewhere in this Agreement, NBPco shall: 3.1.1 perform Network Deployment in accordance with the Implementation Programme, the Wholesale Product Launch Project Plan, the Network Deployment Plan, the Operational Environment Project Plan and the Service Provider Engagement Framework Project Plan so as to Achieve each Milestone by the associated Milestone Date; 3.1.2 perform such activities, tasks, functions, works and services as are necessary to perform Network Deployment in accordance with the Implementation Programme, the Wholesale Product Launch Project Plan, the Network Deployment Plan, the Operational Environment Project Plan and the Service Provider Engagement Framework Project -

Some Aspects of the Breeding Biology of the Swifts of County Mayo, Ireland Chris & Lynda Huxley

Some aspects of the breeding biology of the swifts of County Mayo, Ireland Chris & Lynda Huxley 3rd largest Irish county covering 5,585 square kilometers (after Cork and Galway), and with a reputation for being one of the wetter western counties, a total of 1116 wetland sites have been identified in the county. Project Objectives • To investigate the breeding biology of swifts in County Mayo • To assess the impact of weather on parental feeding patterns • To determine the likelihood that inclement weather significantly affects the adults’ ability to rear young • To assess the possibility that low population numbers are a result of weather conditions and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. Town Nest Nest box COMMON SWIFT – COUNTY MAYO - KNOWN STATUS – 2017 Sites Projects Achill Island 0 0 Aghagower 1 0 Balla 1 1 (3) Ballina 49 1 (6) Ballycastle Ballinrobe 28 1 (6) Ballycastle 0 0 0 Ballycroy 0 In 2018 Ballyhaunis ? In 2018 Killala 7 Bangor 0 In 2018 0 Belmullet 0 In 2018 Castle Burke 2 0 Bangor 49 0 Castlebar 37 4 (48) (12) Crossmolina Charlestown 14 1 (6) 8 Claremorris 15 2 (9) (2) Crossmolina Cong 3 1 (6) Crossmolina 8 1 (6) Foxford Foxford 16 1 (12) Achill Island 16 14 0 21 Killala 7 1 (6) 0 Charlestown Kilmaine 2 0 0 0 2 Kiltimagh 6 1 (6) 14 Kinlough Castle 10 0 Mulranny Turlough Kiltimagh 6 Knock 0 0 Louisburgh ? In 2018 40 Balla 1 0 Knock Mulranny 0 0 Newport 14 1 (6) X X = SWIFTS PRESENT 46 1 Aghagower Shrule 10 1 (6) Castle Burke Swinford 21 1 (6) POSSIBLE NEST SITES X 2 15 Tourmakeady 0 0 TO BE IDENTIFIED Turlough 2 In 2018 Westport -

450 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

450 bus time schedule & line map 450 Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry) View In Website Mode The 450 bus line (Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry): 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM (2) Louisburgh - Dooagh: 5:30 AM - 6:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 450 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 450 bus arriving. Direction: Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh 450 bus Time Schedule (Hudson's Pantry) Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry) 15 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:20 AM - 8:05 PM Monday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dooagh Stop 530301 Tuesday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Keel Stop 530371 Wednesday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dugort Stop 530391 Thursday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dooniver Junction Stop 553011 Friday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Bunnacurry Stop 638031 Saturday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Cashel Stop 638041 Achill Sound Stop 631421 450 bus Info Direction: Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Mulrany Stop 638061 Pantry) Stops: 15 Newport Stop 638111 Trip Duration: 124 min Line Summary: Dooagh Stop 530301, Keel Stop Mill Street Stop 555711 530371, Dugort Stop 530391, Dooniver Junction Grove Park, Westport Stop 553011, Bunnacurry Stop 638031, Cashel Stop 638041, Achill Sound Stop 631421, Mulrany Stop Westport Quay Stop 557161 638061, Newport Stop 638111, Mill Street Stop 555711, Westport Quay Stop 557161, Murrisk Stop Murrisk Stop 500021 500021, Lecanvey Stop 545491, Kilsallagh Stop 557171, Louisburgh Stop 553111 -

TD,MEP, COCO Contacts.Xlsx

TD,MEP & CoCo Contact Details for MEP's, TD's and Councillors TD/MEP/CLLR Mr/Ms Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address4 Phone no Mobile Email Mayo Co Cllr Mr Al Mc Donnell Moorehall Ballyglass Claremorris Co. Mayo 094-9029039 086-8109499 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Austin Francis O'Malley Doughmackeon Roonagh P.O. Louisbourgh Co. Mayo 098-66418 087-2919477 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Blackie K Gavin Sion Hill Castlebar Co. Mayo 094-9022171 087-2490933 [email protected] W'Port Town Cllr Mr Brendan Mulroy 4 St.Patricks Tce. Westport Co. Mayo 087-2824702 [email protected] W'Port Town Cllr Mr Christy Hyland Distillery Court Westport Co Mayo 086-8342208 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Cyril Burke Premier Estate Maloney, I.P.I. Centre Breafy Road Castlebar Co. Mayo 087-6891821 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Damien Ryan Neale Road Ballinrobe Co. Mayo 094-9541444 [email protected] Co.Mayo TD Mr Dara Calleary TD Pearse Street Ballina Co Mayo 096-77613 [email protected] An Taoiseach Mr Enda Kenny TD Tucker Street Castlebar Co Mayo 094-9025600 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Eugene Mc Cormack 49 Knockaphunta Park Castlebar Co. Mayo 094-9023758 086-8101426 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Frank Durcan Westport Road Castlebar Co. Mayo 087-2589091 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Gerry Coyle Doolough Geesala Ballina Co. Mayo 097-82280 087-2441380 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Henry kenny Straide Road Ballyvary Co. -

Silver Strand Silverstrand Has a Safe, Shallow, Sandy Beach of Approximately 0.25Km Bounded on One Side by a Cliff and the Other by Rocks

Silver Strand Silverstrand has a safe, shallow, sandy beach of approximately 0.25km bounded on one side by a cliff and the other by rocks. It is particularly popular with and suitable for young families. It faces directly into Galway Bay giving spectacular views. There is a promenade with parking capacity for about 60 vehicles. It is suitable for swimming at low tide but the beach is largely covered during high tides. It is lifeguarded during the summer months. Blue Flag standard (2005). Barna Golf and Country Club Corbally, Barna, Co. Galway Telephone: +353 91 592677 Fax: +353 91 592674 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bearnagolfclub.com Located approx. 8km from Galway, and 3km north of Bearna village, this golf course is set in typical rugged Connemara countryside with fairways constructed between rocks and heather. The course was designed to suit all abilities. Bearna golf course is already being hailed as one of Ireland's finest. The inspired creativity of its designer R.J. Browne in the siting of tees and sand-based greens in the celebrated beauty of West of Ireland's Connemara landscape has produced a course of glamorously porportioned holes. Water comes into play at thirteen of the eighteen holes, each one boasting unique features which together test the golfer's total repertoire of skills. The final holes especially provide a spectacular finish to a satisfying and memorable experience. Caddy hire available. Dress code is neat & casual. Full canteen facilities available with full bar menu and restaurant. Course designed by Robert J Browne. Course length (m): 6174 Athenry Golf Club Palmerstown, Oranmore, Co. -

Tier 3 Risk Assessment Historic Landfill at Claremorris, Co

CONSULTANTS IN ENGINEERING, ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE & PLANNING TIER 3 RISK ASSESSMENT HISTORIC LANDFILL AT CLAREMORRIS, CO. MAYO Prepared for: Mayo County Council For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Date: September 2020 J5 Plaza, North Park Business Park, North Road, Dublin 11, D11 PXT0, Ireland T: +353 1 658 3500 | E: [email protected] CORK | DUBLIN | CARLOW www.fehilytimoney.ie EPA Export 02-10-2020:04:36:54 TIER 3 RISK ASSESSMENT HISTORIC LANDFILL AT CLAREMORRIS, CO. MAYO User is responsible for Checking the Revision Status of This Document Description of Rev. No. Prepared by: Checked by: Approved by: Date: Changes Issue for Client 0 BF/EOC/CF JON CJC 10.03.2020 Comment Issue for CoA 0 BF/EOC/MG JON CJC 14.09.2020 Application Client: Mayo County Council For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Keywords: Site Investigation, environmental risk assessment, waste, leachate, soil sampling, groundwater sampling. Abstract: This report represents the findings of a Tier 3 risk assessment carried out at Claremorris Historic Landfill, Co. Mayo, conducted in accordance with the EPA Code of Practice for unregulated landfill sites. P2348 www.fehilytimoney.ie EPA Export 02-10-2020:04:36:54 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. -

West Coast, Ireland

West Coast, Ireland (Slyne Head to Erris Head) GPS Coordinates of location: Latitude: From 53° 23’ 58.02”N to 54° 18’ 26.96”N Longitude: From 010° 13” 59.87”W to 009° 59’ 51.98”W Degrees Minutes Seconds (e.g. 35 08 34.231212) as used by all emergency marine services Description of geographic area covered: The region covered is the wild and remote west coast of Ireland, from Slyne Head north of Galway to Erris Head south of Sligo. It includes Killary Harbour, Clew Bay, Black Sod Bay, Belmullet, and the islands of Inishbofin, Inishturk, Clare, Achill, and the Inishkeas. It is an area of incomparable charm and natural beauty where mountains come down to the sea unspoilt by development. It is also an area without marinas, or easy access to marine services. Self-sufficiency is absolutely necessary, along with careful navigation around a rocky lee coastline in prevailing westerlies. A vigilant watch for approach of frequent Atlantic gales must be kept. Inishbofin is reported to be the most common stopover of visiting foreign-flagged yachts in Ireland, of which there are very few on the West coast. Best time to visit is May-September. 1 24 May 2015 Port officer’s name: Services available in area covered: Daria & Alex Blackwell • There are no marinas in the west of Ireland between Galway and Killybegs in Donegal, so services remain difficult to access. Haul out facilities are now available in Kilrush on the Shannon River and elsewhere by special arrangement with crane operators. • Visitor Moorings (Yellow buoy, 15 tons): Achill / Kildavnet Pier, Achill Bridge, Blacksod, Clare Island, Inishturk, Rosmoney (Clew Bay), Leenane. -

Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork

Published by the Stationery Office, Dublin, Ireland. To be purchased from the: Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork. Government Publications Sales Office, Sun Alliance House, Molesworth Street, Dublin 2, or through any bookseller. Prn 443. Price 15.00. July 2003. © Government of Ireland 2003 Material compiled and presented by Central Statistics Office. Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. ISBN 0-7557-1507-1 3 Table of Contents General Details Page Introduction 5 Coverage of the Census 5 Conduct of the Census 5 Production of Results 5 Publication of Results 6 Maps Percentage change in the population of Electoral Divisions, 1996-2002 8 Population density of Electoral Divisions, 2002 9 Tables Table No. 1 Population of each Province, County and City and actual and percentage change, 1996-2002 13 2 Population of each Province and County as constituted at each census since 1841 14 3 Persons, males and females in the Aggregate Town and Aggregate Rural Areas of each Province, County and City and percentage of population in the Aggregate Town Area, 2002 19 4 Persons, males and females in each Regional Authority Area, showing those in the Aggregate Town and Aggregate Rural Areas and percentage of total population in towns of various sizes, 2002 20 5 Population of Towns ordered by County and size, 1996 and 2002 21 6 Population and area of each Province, County, City, urban area, rural area and Electoral Division, 1996 and 2002 58 7 Persons in each town of 1,500 population and over, distinguishing those within legally defined boundaries and in suburbs or environs, 1996 and 2002 119 8 Persons, males and females in each Constituency, as defined in the Electoral (Amendment) (No. -

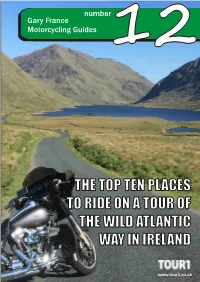

Guide 12 Wild Atlantic

number Gary France Motorcycling Guides 12 THE TOP TEN PLACES TO RIDE ON A TOUR OF THE WILD ATLANTIC WAY IN IRELAND www.tour1.co.uk 1. Doolough Pass The pass is on the R335 road, between Cregganbaun and Delphi, in County Mayo. It Introduction is a good riding road set between scenic mountains and beside a stunning lake. The Wild Atlantic Way is the coast road Doolough Pass is shown on the cover of this on the west coast of Ireland and what a guide. stunning place it is to ride! As it has become more popular in recent years, I have often been asked what are the best parts of the road to ride. Here are my top ten, in order of north to south. Other people may have other thoughts about places that are equally as good, but these are my favourites that I have ridden and seen for myself. 2. Sky Road, Clifden Immediately to the west of Clifden in County Gary France. Galway is Sky Road which runs around a peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean. The Sky Road route takes you up among the hills overlooking Clifden Bay and its offshore islands, Inishturk and Turbot. Be sure to ride around the whole Sky Road loop and I have found clockwise to be the best direction. www.tour1.co.uk 1 3. The Connemara 5. Connor Pass The Connemara is a district on the west coast Connor Pass runs diagonally across the Dingle of Ireland which runs broadly from Killary Peninsula, in County Kerry. -

Achill Heinrich Böll Association, Cashal Achill, Co

Annual Heinrich Böll Weekend May 4th – May 6th 2018 Achill Island Ireland Friday May 4th Full Weekend € 130 19:00 Registration and Welcome Reception. Cyril Gray Hall Dugort 19:30 Official Opening: H.E. Deike Potzel: Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1987 - 1992 Foreign Service Academy of the Federal Foreign Ministry, Bonn. English and French Language and Literature Studies, Humboldt University Berlin. Since 2017 Ambassador, German Embassy, Dublin, Ireland / 2014-2017 Deputy Director-General for Central Services, Foreign Ministry, Berlin / 2012-2014 Head of the Personal Office of Federal President Joachim Gauck/ 2008- 2012/Deputy Head of Division for Personal, Staff Development and Planning, Foreign Ministry, Berlin. Presentation of Essay Prizes by H.E. Deike Potzel. 20:30 Patricia Byrne: The Preacher and the Prelate: Achill Mission Colony and the battle for souls in famine Ireland. Book launch by Sheila McHugh with a response to the book by Hilary Tulloch and reading by Patricia Byrne. The Preacher and the Prelate tells the extraordinary story of an audacious fight for souls on famine- ravaged Achill Island in the nineteenth century. Religious ferment sweeps Ireland in the early 1800s and evangelical clergyman Edward Nangle sets out to lift the destitute people of Achill out of degradation and idolatry through his Achill Mission Colony. A settlement grows up on the slopes of Slievemore with cultivated fields, schools, a printing press and hospital. The Achill Mission colony attracts attention and visitors from far afield. In the years of the Great Famine the ugly charge of ‘souperism’, offering food and material benefits in return for religious conversion, tainted the Achill Mission’s work. -

Route 978 Belmullet to Castlebar

Timetable Route 978 Belmullet to Fares Castlebar FARES Adult Adult Adult Student Student Student Child Child Child Child BAND FTP single return 7-day single day return 7-day single day return 7-day Under 5’s A €2.00 €3.50 €14.00 €1.50 €2.50 €10.00 €1.00 €1.50 €6.00 €0.00 €0.00 B €3.00 €5.00 €20.00 €2.00 €3.50 €14.00 €1.50 €2.50 €10.00 €0.00 €0.00 B C €5.00 €8.50 €34.00 €3.50 €6.00 €24.00 €2.50 €4.00 €16.00 €0.00 €0.00 D €6.00 €10.00 €40.00 €4.00 €7.00 €28.00 €3.00 €5.00 €20.00 €0.00 €0.00 E €7.00 €12.00 €48.00 €5.00 €8.50 €34.00 €3.50 €6.00 €24.00 €0.00 €0.00 F €8.00 €13.00 €52.00 €5.50 €9.00 €36.00 €4.00 €6.50 €26.00 €0.00 €0.00 G €10.00 €15.00 €60.00 €7.00 €11.00 €44.00 €5.00 €7.50 €30.00 €0.00 €0.00 All under 5 year olds are carried free of charge. ADULT FARE STRUCTURE Castlebar Gweesala Mulranny Newport Adult Fare Belmullet Bunnahowen Bangor Erris Ballycroy PO Stephen A Community Doherty's Chamber Structure Chapel Street Post office Centra Post office Garvey Way Centre Filling Station Shop Bus Stop Belmullet Chapel Street €2.00 €2.00 €3.00 €5.00 €7.00 €8.00 €10.00 Bunnahowen Post office €2.00 €3.00 €5.00 €6.00 €8.00 €10.00 Gweesala €2.00 €3.00 €5.00 €7.00 €8.00 Community Centre Bangor Erris Centra €2.00 €3.00 €6.00 €8.00 Ballycroy PO Post office €2.00 €3.00 €6.00 Mulranny Doherty's €2.00 €5.00 Filling Station Newport Chamber Shop €2.00 Castlebar Stephen Garvey Way Bus Stop Mayo Timetable For more information Tel: 094 9005150 978 Belmullet - Castlebar Castlebar - Turlough Museum Email: [email protected] Day: Monday to Saturday Day: Monday to Saturday Web: www.transportforireland.ie/tfi-local-link/ BELMULLET - CASTLEBAR CASTLEBAR - TURLOUGH MUSEUM Operated by: Local Link Mayo, Departs Stops Mon - Sat Departs Stops Mon - Sat Glenpark House, The Mall, Castlebar, Belmullet Chapel Street* 07:00 11:20 Castlebar Rail Station* 13:10 - Co.